Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Latest Developments and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

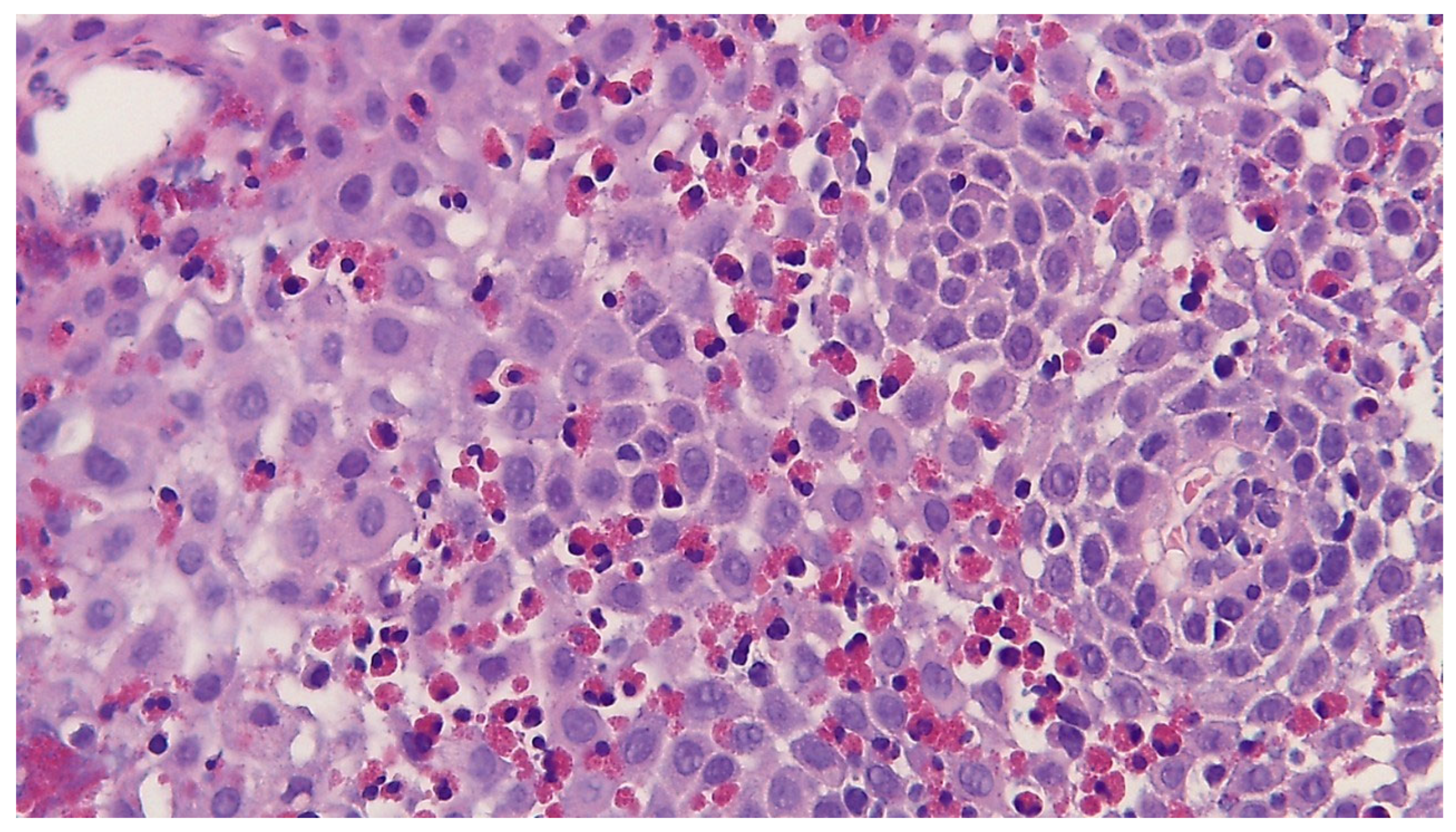

2. Histological Analysis and Diagnostic Criteria

3. Minimally Invasive Biomarkers

- Blood-based biomarkers, mainly detectable in serum or plasma;

- Non-blood-derived biomarkers, including those found in saliva, urine, stool, or other bodily fluids.

4. Minimally Invasive Biomarkers in Blood

4.1. Eosinophil-Associated Biomarkers

4.1.1. Eotaxin-3 (CCL26)

4.1.2. Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP)

4.1.3. Major Basophil Protein (MBP)

4.1.4. Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin (EDN/EPX)

4.1.5. Galectin-10

4.2. Non-Eosinophil-Associated Biomarkers

4.2.1. Interleukins (IL-15 and IL-4, IL-5, and IL-33, IL-13)

4.2.2. IgG4

4.2.3. 15(S)-HETE

4.2.4. MicroRNAs in Plasma and Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

4.2.5. mRNA from Blood

5. Minimally Invasive Biomarkers in Other Biological Fluids (Saliva, Mucus, and Urine)

5.1. MicroRNAs as Potential Salivary Biomarkers

5.2. Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP) in Mucus Secretions

5.3. Urine Sample: 3-Bromotyrosine

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EoE | Eosinophilic Esophagitis |

| Th2 | T-Helper Type 2 (immune response) |

| Eos | Eosinophil |

| HPF | High-Power Field |

| PPI | Proton Pump Inhibitor |

| ESPGHAN | European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| EoEHSS | Eosinophilic Esophagitis Histology Scoring System |

| CCL26 | Chemokine (C–C motif) Ligand 26 (Eotaxin-3) |

| ECP | Eosinophil Cationic Protein |

| MBP | Major Basic Protein |

| EDN/EPX | Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin/Eosinophil Protein X |

| CLC | Charcot–Leyden Crystal Protein (Galectin-10) |

| 3-BT | 3-Bromotyrosine |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-4, | Interleukin 4 |

| IL-5 | Interleukin 5 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin 13 |

| IL-15 | Interleukin 15 |

| IL-33 | Interleukin 33 |

| IgG4 | Immunoglobulin G4 |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| 15(S)-HETE | 15(S)-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid |

| miRNA/miR | MicroRNA |

| pEVs | Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles |

| EVs | Extracellular Vesicles |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| TCRδ/TCR | T-Cell Receptor Delta/T-Cell Receptor |

| Jα18 | Joining Alpha Segment 18 (T-cell receptor gene segment) |

| CD274 | Cluster of Differentiation Markers 274 |

| CD101 | Cluster of Differentiation Markers 101 |

| CXCR6 | C-X-C Chemokine Receptor 6 |

| FCεRII/FCεRI | Low-Affinity/High-Affinity IgE Receptor |

| AEC | Absolute Eosinophil Count |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TSLP | Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin |

| EREFS | Endoscopic Reference Score for Eosinophilic Esophagitis |

References

- Dobbins, J.W.; Sheahan, D.G.; Behar, J. Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis with Esophageal Involvement. Gastroenterology 1977, 72, 1312–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teele, R.; Katz, A.; Goldman, H.; Kettell, R. Radiographic Features of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis (Allergic Gastroenteropathy) of Childhood. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1979, 132, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsik, J.; Małecka-Wojciesko, E. Eosinophilic Esophagitis—What Do We Know So Far? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votto, M.; De Filippo, M.; Castagnoli, R.; Delle Cave, F.; Giffoni, F.; Santi, V.; Vergani, M.; Caffarelli, C.; De Amici, M.; Marseglia, G.L.; et al. Non-Invasive Biomarkers of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Acta Biomedica Atenei Parm. 2021, 92, e2021530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liacouras, C.A.; Furuta, G.T.; Hirano, I.; Atkins, D.; Attwood, S.E.; Bonis, P.A.; Burks, A.W.; Chehade, M.; Collins, M.H.; Dellon, E.S.; et al. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Updated Consensus Recommendations for Children and Adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 3–20.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burk, C.M.; Shreffler, W.G. Triggers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): The Intersection of Food Allergy and EoE. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 153, 1500–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spergel, J.M.; Book, W.M.; Mays, E.; Song, L.; Shah, S.S.; Talley, N.J.; Bonis, P.A. Variation in Prevalence, Diagnostic Criteria, and Initial Management Options for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases in the United States. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 52, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amil-Dias, J.; Oliva, S.; Papadopoulou, A.; Thomson, M.; Gutiérrez-Junquera, C.; Kalach, N.; Orel, R.; Auth, M.K.H.; Nijenhuis-Hendriks, D.; Strisciuglio, C.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children: An Update from the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 79, 394–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellon, E.S.; Liacouras, C.A.; Molina-Infante, J.; Furuta, G.T.; Spergel, J.M.; Zevit, N.; Spechler, S.J.; Attwood, S.E.; Straumann, A.; Aceves, S.S.; et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1022–1033.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, S.; Savarino, E.; Savarino, V.; Mion, F. Eosinophilic Oesophagitis: From Physiopathology to Treatment. Dig. Liver Dis. 2013, 45, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Săsăran, M.O.; Bănescu, C. Role of Salivary miRNAs in the Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Mini-Review of Available Evidence. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1228482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshaiah, S.U.; Kandikattu, H.K.; Yadavalli, C.S.; Mishra, A. Eosinophils and T Cell Surface Molecule Transcript Levels in the Blood Differentiate Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE) from GERD. Int. J. Basic Clin. Immunol. 2021, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dellon, E.S.; Muir, A.B.; Katzka, D.A.; Shah, S.C.; Sauer, B.G.; Aceves, S.S.; Furuta, G.T.; Gonsalves, N.; Hirano, I. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 120, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odze, R.D. Pathology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: What the Clinician Needs to Know. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.H.; Martin, L.J.; Alexander, E.S.; Boyd, J.T.; Sheridan, R.; He, H.; Pentiuk, S.; Putnam, P.E.; Abonia, J.P.; Mukkada, V.A.; et al. Newly Developed and Validated Eosinophilic Esophagitis Histology Scoring System and Evidence that It Outperforms Peak Eosinophil Count for Disease Diagnosis and Monitoring: Eosinophilic Esophagitis Pathology. Dis. Esophagus 2016, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, M.; Gui, D. The Pathologic Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Time for Reassessment. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2025, 149, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safroneeva, E.; Straumann, A.; Coslovsky, M.; Zwahlen, M.; Kuehni, C.E.; Panczak, R.; Haas, N.A.; Alexander, J.A.; Dellon, E.S.; Gonsalves, N.; et al. Symptoms Have Modest Accuracy in Detecting Endoscopic and Histologic Remission in Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 581–590.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucendo, A.J.; Molina-Infante, J.; Arias, Á.; Von Arnim, U.; Bredenoord, A.J.; Bussmann, C.; Amil Dias, J.; Bove, M.; González-Cervera, J.; Larsson, H.; et al. Guidelines on Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Evidence-based Statements and Recommendations for Diagnosis and Management in Children and Adults. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2017, 5, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, C. Eotaxin-3 and a Uniquely Conserved Gene-Expression Profile in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Aponte, C.; Torres-Silva, J.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, E.; Gonzalez-Benitez, L.; Wiscovich-Torres, M.; Camacho, C.; Velazquez, V. Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Serum Eotaxin-3 Levels: A Non-Invasive Method to Monitor Disease Activity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, AB261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, S.; Yu, L.; Hahm, E.; Schwarz, S.M.; Park, S.S.; Bukhari, Z.; Lin, B.; Gupta, R.; Weedon, J.; Geraghty, P. Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Searching for Serologic Markers. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2022, 52, 642–650. [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz, C. Serum Eosinophilic Cationic Protein Is Correlated with Food Impaction and Endoscopic Severity in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 30, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, T.A.; Carneiro, A.P.; Narciso, A.S.; Barros, C.P.; Alves, D.A.; Marson, L.B.; Tunala, T.; de Alcântara, T.M.; de Pavia Maia, Y.C.; Briza, P.; et al. Eosinophilic Esophagitis Auxiliary Diagnosis Based on a Peptide Ligand to Eosinophil Cationic Protein in Esophageal Mucus of Pediatric Patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.A.; Gleich, G.J.; Limaye, N.S.; Crispin, H.; Robson, J.; Fang, J.; Saffari, H.; Clayton, F.; Leiferman, K.M. Eosinophil Granule Major Basic Protein 1 Deposition in Eosinophilic Esophagitis Correlates with Symptoms Independent of Eosinophil Counts. Dis. Esophagus 2019, 32, doz055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, J.B.; Ackerman, S.J.; Chehade, M.; Amsden, K.; Riffle, M.E.; Wang, M.; Du, J.; Kleinjan, M.L.; Alumkal, P.; Gray, E.; et al. Noninvasive Biomarkers Identify Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Prospective Longitudinal Study in Children. Allergy 2021, 76, 3755–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.B.; Nylund, C.M.; Baker, T.P.; Ally, M.; Reinhardt, B.; Chen, Y.-J.; Nazareno, L.; Moawad, F.J. Longitudinal Evaluation of Noninvasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 51, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnion, K.M.; Willis, L.K.; Minto, H.B.; Burch, T.C.; Werner, A.L.; Shah, T.A.; Krishna, N.K.; Nyalwidhe, J.O.; Maples, K.M. Eosinophil Quantitated Urine Kinetic. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 116, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbinowska, J.; Wiatrak, B.; Waśko-Czopnik, D. Searching for Noninvasive Predictors of the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Eosinophilic Esophagitis—The Importance of Biomarkers of the Inflammatory Reaction Involving Eosinophils. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkateshaiah, S.U.; Kandikattu, H.K.; Mishra, A. Significance of Interleukin (IL)-15 in IgE Associated Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE). Int. J. Basic Clin. Immunol. 2020, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, S.; Shoda, T.; Ishimura, N.; Ohta, S.; Ono, J.; Azuma, Y.; Okimoto, E.; Izuhara, K.; Nomura, I.; Matsumoto, K.; et al. Serum Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. Intern. Med. 2017, 56, 2819–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.; Lin, E.; Saffari, H.; Qeadan, F.; Pyne, A.; Firszt, R.; Robson, J.; Gleich, G. Food-specific Antibodies in Oesophageal Secretions: Association with Trigger Foods in Eosinophilic Oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visaggi, P.; Solinas, I.; Baiano Svizzero, F.; Bottari, A.; Barberio, B.; Lorenzon, G.; Ghisa, M.; Maniero, D.; Marabotto, E.; Bellini, M.; et al. Non-Invasive and Minimally Invasive Biomarkers for the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis beyond Peak Eosinophil Counts: Filling the Gap in Clinical Practice. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Herzlinger, M.; Cao, W.; Noble, L.; Yang, D.; Shapiro, J.; Kurtis, J.; LeLeiko, N.; Resnick, M. Utility of 15(S)-HETE as a Serological Marker for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulin, H.; Mansouri, L.; Altman, M.; Merid, S.K.; Lundahl, J.; Nilsson, C.; Säfholm, J. Biomarkers for a Less Invasive Strategy to Predict Children with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Allergy 2024, 79, 3464–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.X.; Sherrill, J.D.; Wen, T.; Plassard, A.J.; Besse, J.A.; Abonia, J.P.; Franciosi, J.P.; Putnam, P.E.; Eby, M.; Martin, L.J.; et al. MicroRNA Signature in Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis, Reversibility with Glucocorticoids, and Assessment as Disease Biomarkers. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 1064–1075.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarallo, A.; Casertano, M.; Valanzano, A.; Cenni, S.; Creoli, M.; Russo, G.; Damiano, C.; Carissimo, A.; Cioce, A.; Martinelli, M.; et al. MiR-21-5p and miR-223-3p as Treatment Response Biomarkers in Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grueso-Navarro, E.; Rodríguez-Alcolado, L.; Arias-González, L.; Aransay, A.M.; Lozano, J.-J.; Sidorova, J.; Juárez-Tosina, R.; González-Cervera, J.; Lucendo, A.J.; Laserna-Mendieta, E.J. MicroRNAs in Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhaveri, P.B.; Lambert, K.A.; Bogale, K.; Lehman, E.; Alexander, C.; Ishmael, F.; Jhaveri, P.N.; Hicks, S.D. Salivary microRNAs in Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2023, 44, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Sena, M.; Ghaffari, G.; Ishmael, F. MiR-4668 as a Novel Potential Biomarker for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Tanita, K.; Ohuchi, K.; Sato, Y.; Lyu, C.; Kambayashi, Y.; Fujisawa, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Hashimoto, A.; Aiba, S. Increased Serum CCL26 Level Is a Potential Biomarker for the Effectiveness of Anti-PD1 Antibodies in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2020, 30, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Shi, H.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, W.; Mao, P.; Zhong, R.; Liang, Y.; Yang, Z. Association of CCL11, CCL24 and CCL26 with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 67, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K. Noninvasive Markers of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 18, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellon, E.S.; Rusin, S.; Gebhart, J.H.; Covey, S.; Higgins, L.L.; Beitia, R.; Speck, O.; Woodward, K.; Woosley, J.T.; Shaheen, N.J. Utility of a Noninvasive Serum Biomarker Panel for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Prospective Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Jiménez, F.; Ugalde-Triviño, L.; Arias-González, L.; Relaño-Rupérez, C.; Casabona, S.; Pérez-Fernández, M.T.; Martín-Domínguez, V.; Fernández-Pacheco, J.; Laserna-Mendieta, E.J.; Muñoz-Hernández, P.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of the Esophageal Epithelium Reveals Key Features of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Pathophysiology. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 78, 2732–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukerberg, L.; Mahadevan, K.; Selig, M.; Deshpande, V. Oesophageal Intrasquamous IgG4 Deposits: An Adjunctive Marker to Distinguish Eosinophilic Oesophagitis from Reflux Oesophagitis. Histopathology 2016, 68, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoso, A.; Mukkada, V.A.; Lu, S.; Monahan, R.; Cleveland, K.; Noble, L.; Mangray, S.; Resnick, M.B. Expression Microarray Analysis Identifies Novel Epithelial-Derived Protein Markers in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Mod. Pathol. 2013, 26, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Aldana, A.; Jaramillo-Santos, M.; Delgado, A.; Jaramillo, C.; Lúquez-Mindiola, A. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 4598–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; Chen, S.; Lombardo, K.A.; Resnick, M.B.; Mangray, S.; Matoso, A. ALOX15 Immunohistochemistry Aids in the Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis on Pauci-Eosinophilic Biopsies in Children. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2017, 20, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, D.; Yao, W.; Wright, Z.; Sawyers, C.; Tepper, R.; Gupta, S.; Kaplan, M.; Dent, A. Serum MicroRNA-21 as a Biomarker for Allergic Inflammatory Disease in Children. MicroRNA 2015, 4, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, R.A. mRNA Transcripts as Molecular Biomarkers in Medicine and Nutrition. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upparahalli Venkateshaiah, S.; Rayapudi, M.; Kandikattu, H.K.; Yadavalli, C.S.; Mishra, A. Blood mRNA Levels of T Cells and IgE Receptors are Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE). Clin. Immunol. 2021, 227, 108752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sninsky, J.A.; Liu, S.; Eluri, S.; Tsai, Y.S.; Dellon, E.S. CSTB and FABP5 Serum mRNA Differentiate Histologically Active and Inactive Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastro Hep Adv. 2024, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnkvist, K.; Hellman, C.; Lundahl, J.; Halldén, G.; Hedlin, G. Eosinophil Markers in Blood, Serum, and Urine for Monitoring the Clinical Course in Childhood Asthma: Impact of Budesonide Treatment and Withdrawal. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001, 107, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonoff-Cohen, H.; Polavarapu, M. Eosinophil Protein X and Childhood Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2016, 4, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niess, J.H.; Kaymak, T. Eosinophilic Esophagitis Pathogenesis: All Clear? Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2025, 10, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebi Sözener, Z.; Cevhertas, L.; Nadeau, K.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Environmental Factors in Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottyan, L.C.; Maddox, A.; Hoffman, K.; Ray, L.; Forney, C.; Eby, M.; Mingler, M.K.; Kaufman, K.; Dexheimer, P.; Lukac, N.; et al. X Chromosomal Linkage to Eosinophilic Esophagitis Susceptibility. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, AB225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisa, M.; Savarino, V.; Buda, A.; Katzka, D.A.; Savarino, E. Toward a Potential Association between Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Klinefelter Syndrome: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.S.; Martin, L.J.; Collins, M.H.; Kottyan, L.C.; Sucharew, H.; He, H.; Mukkada, V.A.; Succop, P.A.; Abonia, J.P.; Foote, H.; et al. Twin and Family Studies Reveal Strong Environmental and Weaker Genetic Cues Explaining Heritability of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 1084–1092.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S. Salivaomics: The Current Scenario. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2018, 22, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Biomarker | Molecular Class | Biological Matrix | Potential Use | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eosinophil-Associated | Eotaxin-3 (CCL26) | Chemokine-Protein | Serum | Diagnosis, Monitoring and Therapeutic Target | High levels in EoE, but variable correlation with eosinophil count. Potential for monitoring therapy. | Blanchard et al., 2006 [19]; Jimenez-Aponte et al., 2014 [20]; Rabinowitz et al., 2022 [21]. |

| Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP) | Eosinophil Granule Protein | Serum, Esophageal Mucus | Diagnosis, Correlation with Endoscopic Severity. | Sensitivity 80%, specificity 92.8% at cut-off 13.9 μg/mL. Correlates with EREFS and dietary impact. | Cengiz, 2019 [22]; Souza et al., 2022 [23]. | |

| Major Basic Protein (MBP) | Eosinophil Granule Protein | Esophageal Tissue, Serum | Monitoring | Elevated in tissue, but conflicting results in serum. Potential for monitoring therapy response. | Peterson et al., 2019 [24]; Wechsler et al., 2021 [25]. | |

| Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin (EDN/EPX) | Eosinophil RNAse-Protein | Serum, Feces, Esophageal Mucus | Diagnosis, Monitoring and Prediction of Response to PPI Drugs | EDN concentrations distinguish active EoE from remission and correlate with peak eosinophil counts; included in validated multi-analyte panels for non-invasive monitoring. | Min et al., 2017 [26]; Wechsler et al., 2021 [25]. | |

| Galectin-10 (CLC) | Eosinophilic Cytoplasmatic Protein | Serum | Diagnosis (in Combination with Other Biomarkers). | Elevated Gal-10, particularly when combined with EDN and ECP, enhances diagnostic accuracy; adult data are presently scarce. | Wechsler et al., 2021 [25]. | |

| 3-Bromotyrosine (3-BT) | Brominated type amino acid chemical compounds | Urine | Diagnosis and Monitoring | Promising but detection techniques are expensive. | Cunnion et al., 2016 [27]. | |

| Non-Eosinophil-Associated | Interleukine (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-15, IL-33) | Cytokine-protein | Serum | Pathogenetic Role, Monitoring Therapy | Circulating Th2 cytokines show inconsistent elevation; IL-13 rose after PPI therapy but lacked correlation with eosinophil density, limiting their utility as stand-alone biomarkers. | Sarbinowska et al., 2021 [28]; Venkateshaiah et al., 2020 [29]; Ishihara et al., 2017 [30]. |

| Total or Specific IgG4 | Antibodies-proteine | Serum | Differential Diagnosis (vs. GERD), Monitoring Response to Therapy | IgG4 levels exceed those in GERD and decline with effective therapy, supporting a role in treatment monitoring, yet high inter-individual variability precludes diagnostic use. | Peterson et al., 2020 [31]; Visaggi et al., 2023 [32]. | |

| 15(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15(S)-HETE) | Polyunsatured fatty acid | Serum | Diagnosis (in Combination with Other Biomarkers). | Elevated in active EoE and remission, but not included in diagnostic panels due to lack of specificity. | Lu et al., 2018 [33]; Thulin et al., 2024 [34]. | |

| Circulating miRNAs | miR-146a, miR-223, miR-21-5p | microRNA | Plasma | Diagnosis, Monitoring Response to Glucocorticoids | miR-146a and miR-223 reversible post-therapy. miR-21-5p elevated in EoE. | Lu et al., 2012 [35]; Tarallo et al., 2025 [36]. |

| miR-10b-5p, miR-221-3p | Extracellular Vescicles (pEVs) | Diagnosis | Differences between active EoE and controls | Grueso-Navarro et al., 2025 [37]. | ||

| miR-205-5p, miR-4668-5p | Saliva | Diagnosis, Monitoring Therapy | miR-205-5p differentiates EoE vs. controls. miR-4668-5p reduced post corticosteroid therapy. | Jhaveri et al., 2023 [38]; Bhardwaj et al., 2020 [39]. | ||

| Whole-Blood mRNA Panel | CD274, CD101, CXCR6, TCRδ, Jα18, FCεRII | mRNA | Whole Blood | Differential Diagnosis (vs. GERD), Monitoring Response to Therapy | Promising panel to discriminate EoE from GERD and monitor activity. | Venkateshaiah et al., 2021 [12] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marulo, S.; Macrì, A.; Mirabelli, P.; Aurino, L.; Turco, R.; Franca, R.A.; Quitadamo, P. Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Latest Developments and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8576. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238576

Marulo S, Macrì A, Mirabelli P, Aurino L, Turco R, Franca RA, Quitadamo P. Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Latest Developments and Future Directions. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8576. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238576

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarulo, Serena, Alessandra Macrì, Peppino Mirabelli, Laura Aurino, Rossella Turco, Raduan Ahmed Franca, and Paolo Quitadamo. 2025. "Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Latest Developments and Future Directions" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8576. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238576

APA StyleMarulo, S., Macrì, A., Mirabelli, P., Aurino, L., Turco, R., Franca, R. A., & Quitadamo, P. (2025). Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Latest Developments and Future Directions. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8576. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238576