Cucurbiturils in Oxygen Delivery and Their Potential in Anemia Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

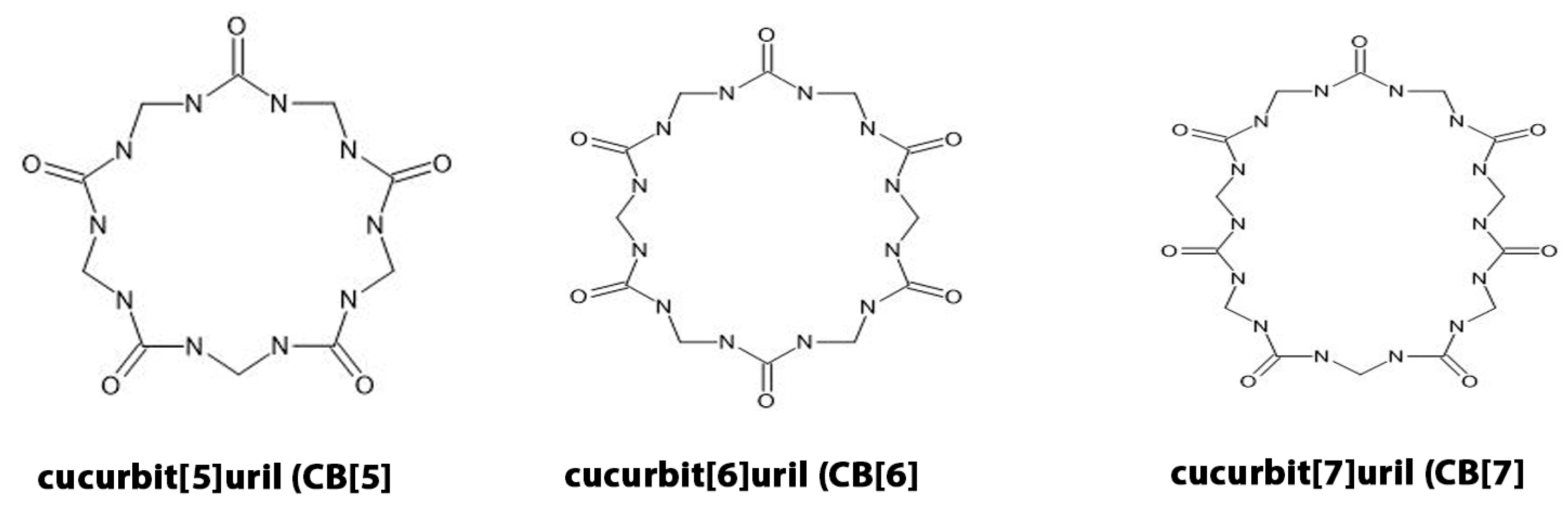

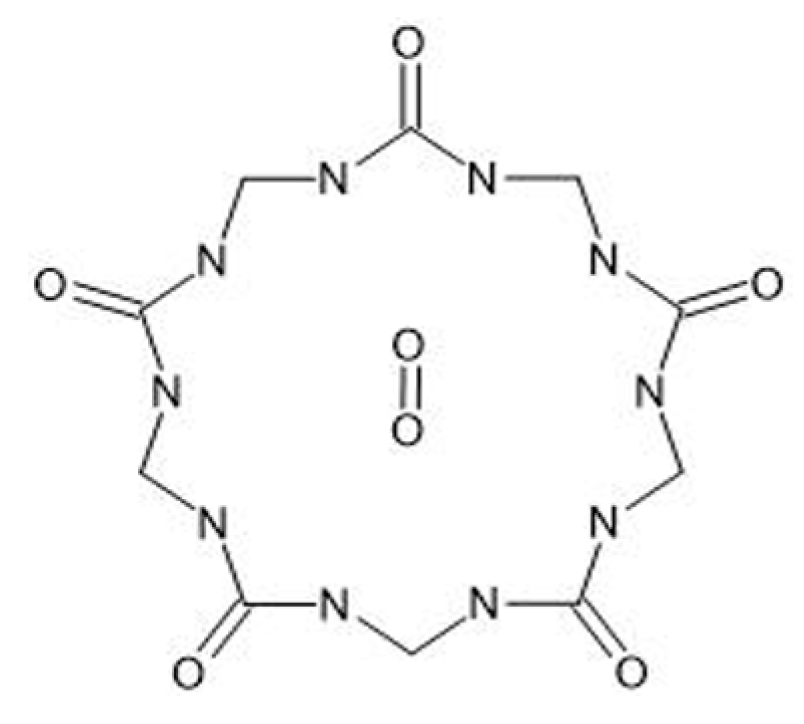

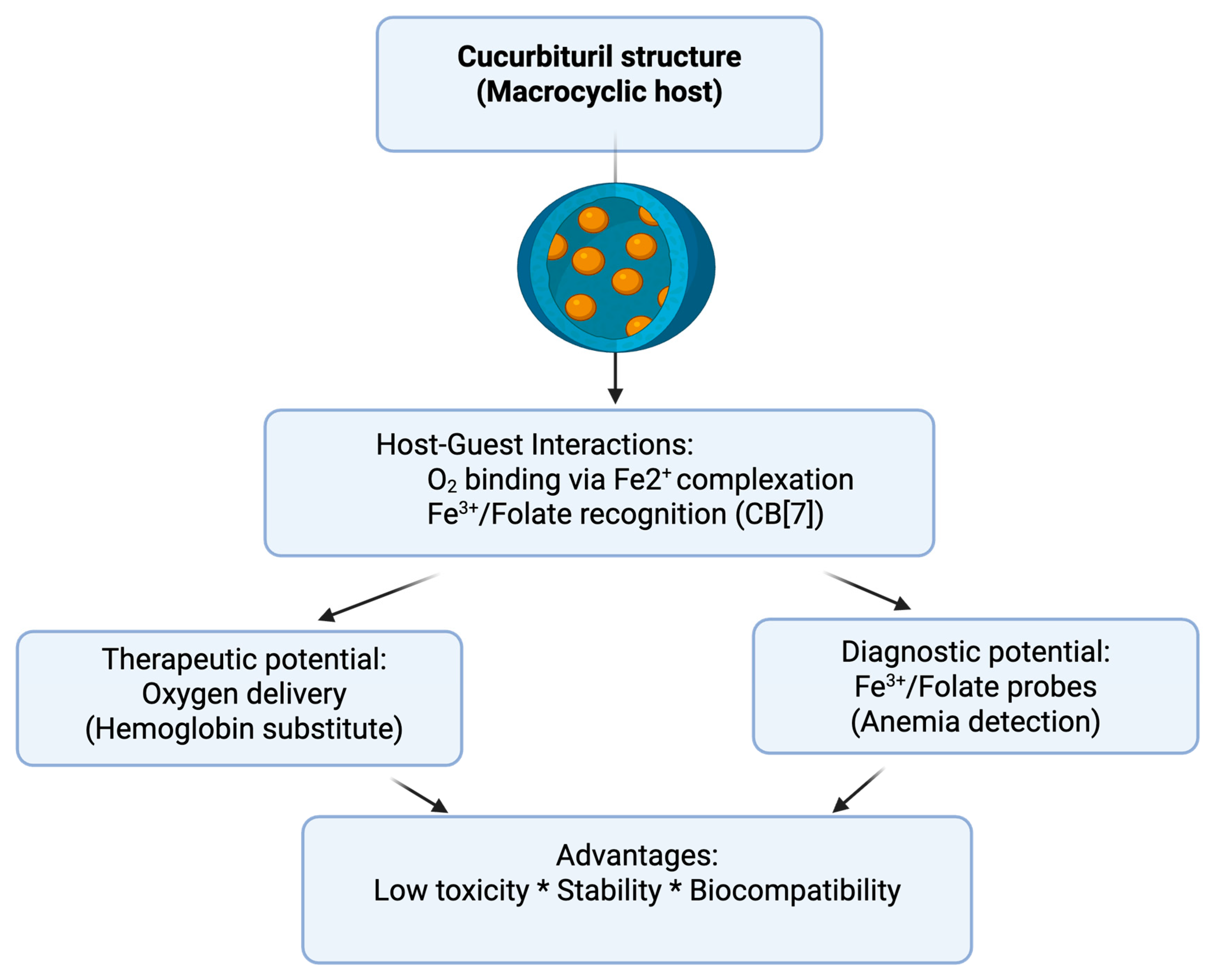

2. Cucurbiturils—Structure and Properties

2.1. Discovery of Cucurbiturils: Early Studies and Applications

2.2. Molecular Structure and Key Features of Cucurbiturils

2.3. Physicochemical Properties and Relevance for Oxygen Transport

3. Mechanism of Action of Cucurbiturils in Oxygen Transport

3.1. Stability of the Cucurbituril–Oxygen Complex

3.2. Biocompatibility of Cucurbiturils—Relevant Preclinical and Clinical Studies

3.3. Applicability of Cucurbiturils in Anemia Treatment—Current Status and Perspectives

4. Advantages of Cucurbituril Applications and Future Research Directions

4.1. Benefits of Cucurbiturils Compared with Other Therapeutic Approaches

4.2. Potential Biomedical Applications of Cucurbiturils

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sen Gupta, A. Hemoglobin-based Oxygen Carriers: Current State-of-the-art and Novel Molecules. Shock 2019, 52, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanto, N.; Mondal, H.; Park, Y.-J.; Jee, J.-P. Therapeutic delivery of oxygen using artificial oxygen carriers demonstrates the possibility of treating a wide range of diseases. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.; Berthault, P.; Nguyen, A.L.; Pruvost, A.; Barruet, E.; Rivollier, J.; Heck, M.-P.; Prieur, B. Cucurbit[5]uril derivatives as oxygen carriers. Supramol. Chem. 2019, 31, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, T.; Chang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y. Supramolecular complexation between cucurbit[7]uril and folate and analytical applications. J. Chem. Res. 2022, 46, 17475198211066489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, W.; Bian, B.; Tao, Z.; Xiao, X. A highly selective fluorescent chemosensor probe for detection of Fe3+ and Ag+ based on supramolecular assembly of cucurbit[10]uril with a pyrene derivative. Dye. Pigment. 2020, 176, 108235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, M.Y.; Hwang, I.; Kim, K. Introduction: History and Development. In Cucurbiturils and Related Macrocycles; Kim, K., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-1-78801-500-4. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, S.J.; Kasera, S.; Rowland, M.J.; Del Barrio, J.; Scherman, O.A. Cucurbituril-Based Molecular Recognition. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12320–12406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichierri, F. Cucurbituril—Molecule of the Month March 2006 [Archived Version]. Figshare; 2017. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/online_resource/Cucurbituril_-_Molecule_of_the_Month_March_2006_Archived_version_/5433397 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Freeman, W.A.; Mock, W.L.; Shih, N.Y. Cucurbituril. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 7367–7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, W.L.; Shih, N.Y. Host-guest binding capacity of cucurbituril. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 3618–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, K.I.; Nau, W.M. Cucurbiturils: From synthesis to high-affinity binding and catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 394–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Jung, I.-S.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, E.; Kang, J.-K.; Sakamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kim, K. New Cucurbituril Homologues: Syntheses, Isolation, Characterization, and X-ray Crystal Structures of Cucurbit[ n ]uril (n = 5, 7, and 8). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.; Arnold, A.P.; Blanch, R.J.; Snushall, B. Controlling Factors in the Synthesis of Cucurbituril and Its Homologues. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 8094–8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagona, J.; Fettinger, J.C.; Isaacs, L. Cucurbit[ n ]uril Analogues. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3745–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Samal, S.; Selvapalam, N.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, K. Cucurbituril Homologues and Derivatives: New Opportunities in Supramolecular Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Huang, B.; Xiao, B.; Chang, S.; Podalko, M.; Nau, W.M. Stabilization of Guest Molecules inside Cation-Lidded Cucurbiturils Reveals that Hydration of Receptor Sites Can Impede Binding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202313864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Assaf, K.I.; Nau, W.M. Applications of Cucurbiturils in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.K.Y.; Dattani, N.D.; Marsden, P.A.; El-Beheiry, M.H.; Grocott, H.P.; Liu, E.; Biro, G.P.; David Mazer, C.; Hare, G.M.T. Reassessing the risk of hemodilutional anemia: Some new pieces to an old puzzle. Can. J. Anesth. 2010, 57, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.D. Anemia and red blood cell transfusion in the adult non-bleeding patient. Ann. Blood 2022, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H. Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers: Where Are We Now in 2023? Medicina 2023, 59, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Jung, E.-A.; Kim, J.-E. Perfluorocarbon-based artificial oxygen carriers for red blood cell substitutes: Considerations and direction of technology. J. Pharm. Investig. 2024, 54, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaco, V.; Jadhav, S.R.; Bandi, S.P.; Datta, D.; Dhas, N.; Thakur, G.; Ramesh, B.V.; Alizadeh, B. Multifunctional application of supramolecular cucurbiturils as encapsulating hosts in drug delivery: A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 681, 125801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nau, W.M.; Florea, M.; Assaf, K.I. Deep Inside Cucurbiturils: Physical Properties and Volumes of their Inner Cavity Determine the Hydrophobic Driving Force for Host–Guest Complexation. Isr. J. Chem. 2011, 51, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagona, J.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Chakrabarti, S.; Isaacs, L. The Cucurbit[ n ]uril Family. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4844–4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktanova, A.; Abramova, T.; Pashkina, E.; Boeva, O.; Grishina, L.; Kovalenko, E.; Kozlov, V. Assessment of the Biocompatibility of Cucurbiturils in Blood Cells. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunova, V.D.; Cullinane, C.; Brix, K.; Nau, W.M.; Day, A.I. Toxicity of cucurbit[7]uril and cucurbit[8]uril: An exploratory in vitro and in vivo study. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, R.; Floriano, R.S.; Isaacs, L.; Rowan, E.G.; Wheate, N.J. The ex vivo neurotoxic, myotoxic and cardiotoxic activity of cucurbituril-based macrocyclic drug delivery vehicles. Toxicol. Res. 2014, 3, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chan, J.Y.W.; Yang, X.; Wyman, I.W.; Bardelang, D.; Macartney, D.H.; Lee, S.M.Y.; Wang, R. Developmental and organ-specific toxicity of cucurbit[7]uril: In vivo study on zebrafish models. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 30067–30074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, G.; Nguyen, D.; Wu, J.; Lucas, D.; Ma, D.; Isaacs, L.; Briken, V. Toxicology and Drug Delivery by Cucurbit[n]uril Type Molecular Containers. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin Jeon, Y.; Kim, S.-Y.; Ho Ko, Y.; Sakamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kim, K. Novel molecular drug carrier: Encapsulation of oxaliplatin in cucurbit[7]uril and its effects on stability and reactivity of the drug. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, L.-H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R. A systematic evaluation of the biocompatibility of cucurbit[7]uril in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, S.; Reddersen, K.; Wiegand, C.; Elsner, P.; Hipler, U.-C. Evaluation of cell and hemocompatibility of Cucurbiturils. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 146, 105271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Gao, C.; Yang, J.; Liao, X.; Yang, B. Fluorescent probe based on acyclic cucurbituril to detect Fe3+ ions in living cells. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 122942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Cheng, Q.; Bardelang, D.; Wang, R. Challenges and Opportunities of Functionalized Cucurbiturils for Biomedical Applications. JACS Au 2023, 3, 2356–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, M.; Wang, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in human health and disease. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: Mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashkina, E.; Aktanova, A.; Mirzaeva, I.; Kovalenko, E.; Andrienko, I.; Knauer, N.; Pronkina, N.; Kozlov, V. The Effect of Cucurbit[7]uril on the Antitumor and Immunomodulating Properties of Oxaliplatin and Carboplatin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Macartney, D.H. Cucurbit[7]uril host–guest complexes of the histamine H2-receptor antagonist ranitidine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheshtawy, H.S.; Chatterjee, S.; Assaf, K.I.; Shinde, M.N.; Nau, W.M.; Mohanty, J. A Supramolecular Approach for Enhanced Antibacterial Activity and Extended Shelf-life of Fluoroquinolone Drugs with Cucurbit[7]uril. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskolczy, Z.; Biczók, L. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Berberine Inclusion in Cucurbit[7]uril. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 2499–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; Wallace, L.; Woodward, C.E.; Keene, F.R.; Day, A.I.; Collins, J.G. Cucurbit[10]uril binding of dinuclear platinum(II) and ruthenium(II) complexes: Association/dissociation rates from seconds to hours. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 2078–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Feterl, M.; Warner, J.M.; Day, A.I.; Keene, F.R.; Collins, J.G. Protein binding by dinuclear polypyridyl ruthenium(ii) complexes and the effect of cucurbit[10]uril encapsulation. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 8868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Feng, Q.; Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Xu, C.; Huang, L.; Chen, M.; Liang, F.; Cheng, Y. Near Infrared Light Triggered Cucurbit[7]uril-Stabilized Gold Nanostars as a Supramolecular Nanoplatform for Combination Treatment of Cancer. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 2855–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Park, J.S.; Yeom, J.; Selvapalam, N.; Park, K.M.; Oh, K.; Yang, J.-A.; Park, K.H.; Hahn, S.K.; Kim, K. 3D Tissue Engineered Supramolecular Hydrogels for Controlled Chondrogenesis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Oh, J.; Jeon, W.S.; Selvapalam, N.; Hwang, I.; Ko, Y.H.; Kim, K. A new cucurbit[6]uril-based ion-selective electrode for acetylcholine with high selectivity over choline and related quaternary ammonium ions. Supramol. Chem. 2012, 24, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, Y. Biomedical Applications of Supramolecular Systems Based on Host–Guest Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7794–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murkli, S.; Klemm, J.; Brockett, A.T.; Shuster, M.; Briken, V.; Roesch, M.R.; Isaacs, L. In Vitro and In Vivo Sequestration of Phencyclidine by Me4 Cucurbit[8]uril. Chem. A Eur. J. 2021, 27, 3098–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommidi, S.S.R.; Smith, B.D. Supramolecular Complexation of Azobenzene Dyes by Cucurbit[7]uril. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 8431–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockus, A.T.; Smith, L.C.; Grice, A.G.; Ali, O.A.; Young, C.C.; Mobley, W.; Leek, A.; Roberts, J.L.; Vinciguerra, B.; Isaacs, L.; et al. Cucurbit[7]uril–Tetramethylrhodamine Conjugate for Direct Sensing and Cellular Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 16549–16552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cucurbituril/Derivative | Structural Feature/Modification | Biomedical Application | Potential/Perspective | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perhydroxy-CB[5] | Hydroxyl functionalization | Enhanced oxygen-binding capacity | Potential hemoglobin substitute for O2 transport | [3] |

| 2 | CB[6] derivatives (mono-/perfunctionalized) | Surface functionalization | Macrocystic vesicles for therapy and bioimaging | Drug delivery, bioimaging, tissue engineering | [34] |

| 3 | CB[6] hydrogels | Supramolecular hydrogel structure | 3D tissue-mimicking scaffold | Guided chondrogenesis, cartilage regeneration | [44] |

| 4 | CB[6] sensor derivative | Selective binding sites | Acetylcholine detection (separated from choline) | Biosensing applications | [45] |

| 5 | CB[7] | Native or functionalized macrocycle | Cell targeting, molecular linking, fluorescence imaging, drug delivery | Nanomedicine, gene therapy, molecular machines | [11] |

| CB[7] | Supramolecular inclusion of azobenzene dyes; photoisomerizable guest molecules encapsulated in CB[7] cavity | Light-responsive systems (photo-controlled drug release, imaging probes); modulation of azobenzene photophysics by encapsulation | Development of photo-switchable drug carriers, controlled release systems, and optical biosensors; potential in precision medicine and spatiotemporal control of therapy | [48] | |

| 6 | Fluorescent CB[7] | Fluorescent tagging | Protein localization, membrane fusion monitoring, deep tissue imaging | Advanced bioimaging, diagnostics | [49] |

| 7 | CB[8] | Large internal cavity | Binding of large molecules or two guests | Complex formation for supramolecular systems | [11] |

| 8 | Tetramethyl-CB[8] | Methyl substitution | Improved solubility of drugs, antidote for overdoses | Detoxification and pharmaceutical solubility enhancement | [47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papiu, D.; Nadaban, A.; Palcu, A.; Sasu, A.; Mara, G.; Albu, P.; Boru, C.; Cotoraci, C. Cucurbiturils in Oxygen Delivery and Their Potential in Anemia Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238571

Papiu D, Nadaban A, Palcu A, Sasu A, Mara G, Albu P, Boru C, Cotoraci C. Cucurbiturils in Oxygen Delivery and Their Potential in Anemia Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238571

Chicago/Turabian StylePapiu, Daniel, Alexandra Nadaban, Adelina Palcu, Alciona Sasu, Gabriela Mara, Paul Albu, Casiana Boru, and Coralia Cotoraci. 2025. "Cucurbiturils in Oxygen Delivery and Their Potential in Anemia Management" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238571

APA StylePapiu, D., Nadaban, A., Palcu, A., Sasu, A., Mara, G., Albu, P., Boru, C., & Cotoraci, C. (2025). Cucurbiturils in Oxygen Delivery and Their Potential in Anemia Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8571. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238571