Trends in Mortality from Diabetes and Other Non-Communicable Diseases Among Sri Lankan Adults: A Retrospective Population-Based Study, 2004–2020/2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Disease Classification

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

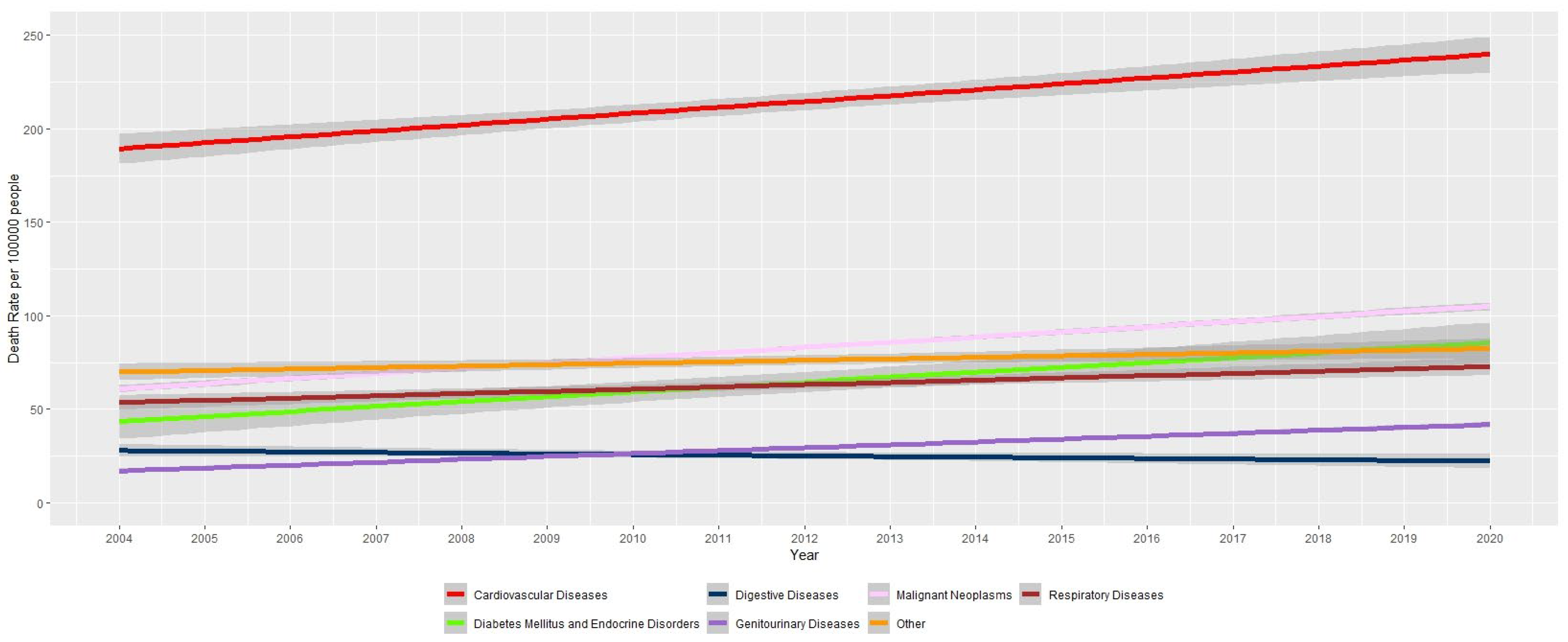

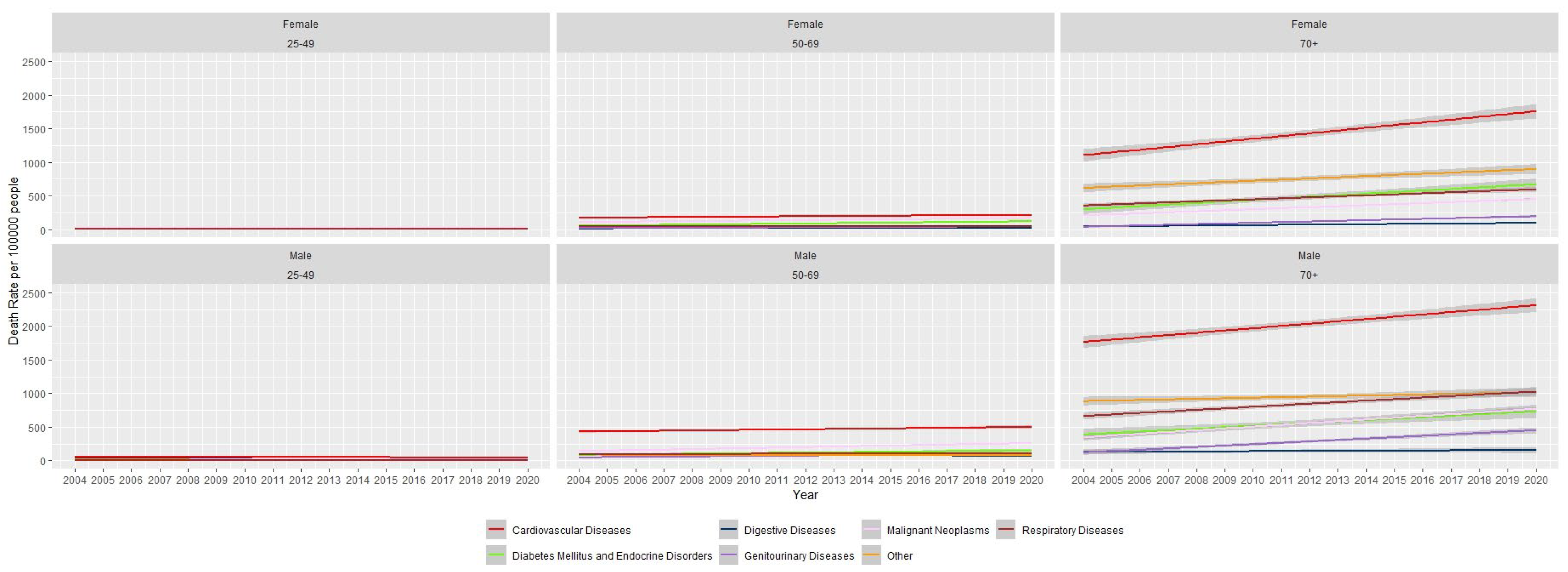

3.1. Total NCD-Related Mortality

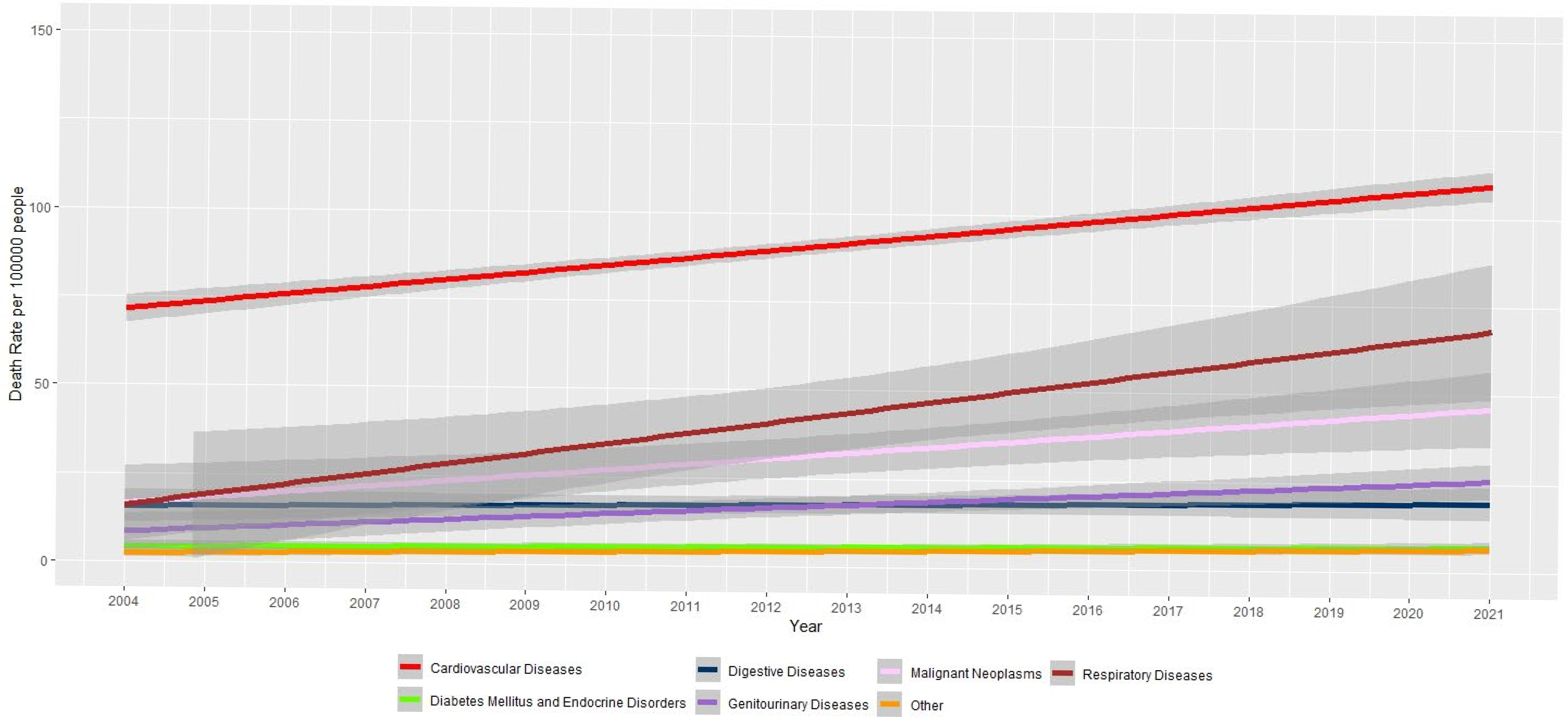

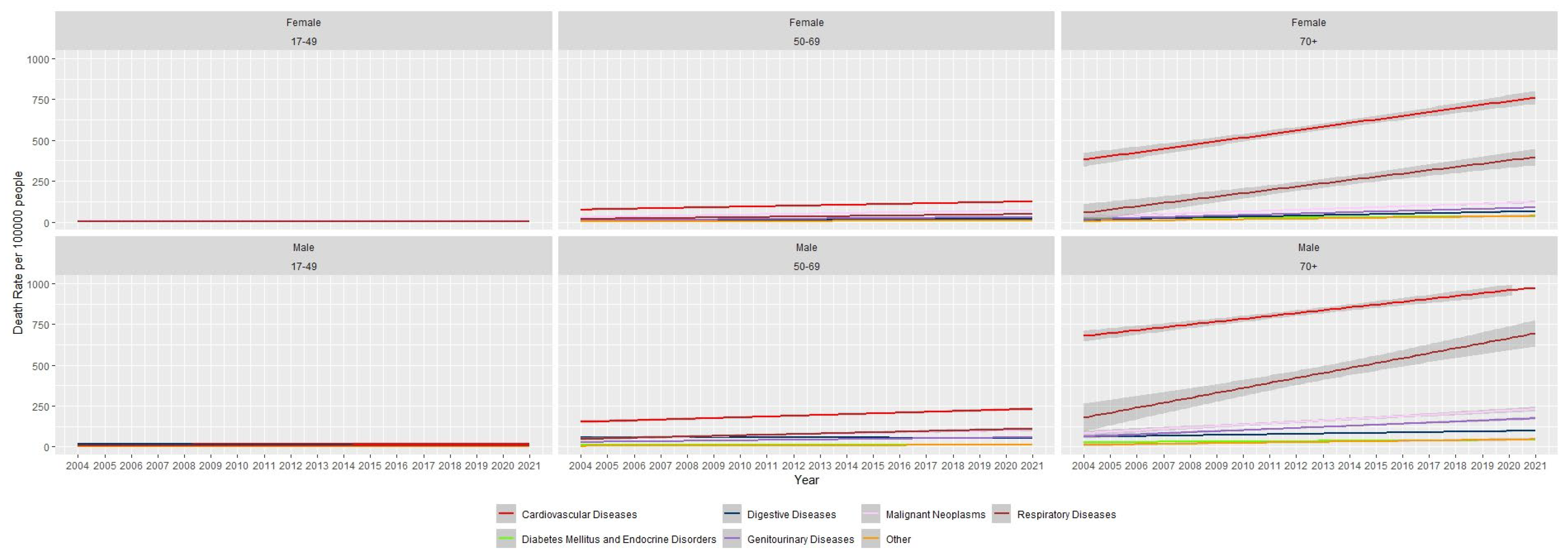

3.2. Results for Hospital Mortality

3.3. Comparison of All Mortality, Hospital Mortality and Non-Hospital Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NCD | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| IMMR | Indoor Morbidity and Mortality Return |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| MN | Malignant Neoplasms |

| DMED | Diabetes Mellitus and Endocrine Disorders |

| NC | Neuropsychiatric Conditions |

| CD | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| RD | Respiratory Diseases |

| DD | Digestive Diseases |

| SD | Skin Diseases |

| MD | Musculoskeletal Diseases |

| GD | Genitourinary Diseases |

Appendix A

| Disease | Gender | Age | Slope | 95% CI | p Value of the Mann–Kendall Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| Cardiovascular Diseases | Female | 17–49 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| 50–69 | 2.94 | 2.38 | 3.51 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 22.45 | 18.34 | 26.55 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 17–49 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.14 | |

| 50–69 | 4.67 | 3.76 | 5.59 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 21.69 | 16.77 | 26.61 | <0.05 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus and Endocrine Disorders | Female | 17–49 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| 50–69 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.31 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 0.83 | 0.51 | 1.15 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 17–49 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.23 | |

| 50–69 | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.27 | 0.16 | ||

| >70 | 0.84 | 0.53 | 1.14 | <0.05 | ||

| Digestive Diseases | Female | 17–49 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.78 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 3.05 | 2.39 | 3.71 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 17–49 | −0.83 | −1.08 | −0.58 | <0.05 | |

| 50–69 | −0.05 | −0.43 | 0.33 | 0.79 | ||

| >70 | 2.24 | 1.59 | 2.89 | <0.05 | ||

| Genitourinary Diseases | Female | 17–49 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.07 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 1.23 | 1.12 | 1.35 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 4.21 | 3.94 | 4.47 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 17–49 | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.39 | |

| 50–69 | 1.73 | 1.25 | 2.22 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 6.54 | 5.55 | 7.54 | <0.05 | ||

| Malignant Neoplasms | Female | 17–49 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.20 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 2.45 | 1.95 | 2.91 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 5.29 | 4.54 | 6.04 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 17–49 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.24 | |

| 50–69 | 3.25 | 2.47 | 4.02 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 8.64 | 7.15 | 10.12 | <0.05 | ||

| Respiratory Diseases | Female | 17–49 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.15 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 1.74 | 1.33 | 2.14 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 20.07 | 14.85 | 25.29 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 17–49 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.43 | |

| 50–69 | 3.68 | 2.56 | 4.80 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 30.36 | 22.10 | 38.63 | <0.05 | ||

| Other | Female | 17–49 | 2.03 | 1.09 | 2.98 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.52 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 1.89 | 1.08 | 2.69 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 17–49 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.59 | |

| 50–69 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.64 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 2.03 | 1.09 | 2.97 | <0.05 | ||

| Disease | Gender | Age | Slope | 95% CI | p Value of the Mann–Kendall Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| Cardiovascular Diseases | Female | 25–49 | −0.25 | −0.37 | −0.14 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 2.68 | 1.82 | 3.55 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 40.82 | 30.00 | 51.63 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 25–49 | −0.62 | −1.21 | −0.05 | <0.05 | |

| 50–69 | 4.37 | 2.43 | 6.32 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 34.11 | 23.85 | 44.35 | <0.05 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus and Endocrine Disorders | Female | 25–49 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.26 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 4.08 | 2.86 | 5.29 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 23.30 | 15.02 | 31.57 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 25–49 | 0.06 | −0.16 | 0.28 | 0.69 | |

| 50–69 | 4.13 | 1.80 | 6.45 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 21.33 | 11.34 | 31.33 | <0.05 | ||

| Digestive Diseases | Female | 25–49 | −0.10 | −0.17 | −0.03 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.98 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 3.27 | 2.19 | 4.35 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 25–49 | −1.70 | −2.99 | −0.41 | <0.05 | |

| 50–69 | −1.31 | −2.50 | 0.24 | 0.09 | ||

| >70 | 1.78 | −2.76 | 6.34 | 0.41 | ||

| Genitourinary Diseases | Female | 25–49 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.48 |

| 50–69 | 1.86 | 1.53 | 2.20 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 9.82 | 8.03 | 11.61 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 25–49 | −0.18 | −0.94 | 0.58 | 0.61 | |

| 50–69 | 3.28 | 2.15 | 4.41 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 20.59 | 16.24 | 24.94 | <0.05 | ||

| Malignant Neoplasms | Female | 25–49 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.15 | 0.49 |

| 50–69 | 3.78 | 2.99 | 4.57 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 15.18 | 13.70 | 16.65 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 25–49 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.16 | 0.92 | |

| 50–69 | 7.43 | 6.42 | 8.43 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 26.36 | 23.27 | 29.44 | <0.05 | ||

| Respiratory Diseases | Female | 25–49 | −0.12 | −0.25 | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | −0.05 | −0.61 | 0.51 | 0.83 | ||

| >70 | 15.01 | 11.44 | 18.56 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 25–49 | −0.34 | −0.51 | −0.19 | <0.05 | |

| 50–69 | 0.41 | −0.55 | 1.38 | 0.36 | ||

| >70 | 22.77 | 16.22 | 28.93 | <0.05 | ||

| Other | Female | 25–49 | −0.08 | −0.15 | —0.02 | <0.05 |

| 50–69 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.93 | <0.05 | ||

| >70 | 17.43 | 9.93 | 24.92 | <0.05 | ||

| Male | 25–49 | −0.68 | −1.00 | −0.35 | <0.05 | |

| 50–69 | −0.26 | −1.15 | 0.62 | |||

| >70 | 8.35 | 0.88 | 15.82 | <0.05 | ||

| All Deaths | Hospital Deaths | Non Hospitalized Deaths | Hospitalized Death Rate (per 100000 People) (D = (B/x) * 100,000) | Non-Hospitalized Death Rate (per 100,000 People) (E = (C/x) * 100,000) | Percentage Increase for Hospitalized Death Rate | Percentage Increase for Non-Hospitalized Death Rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C = A −B) | ||||||||||

| 2004 | 2020 | 2004 | 2020 | 2004 | 2020 | 2004 | 2020 | 2004 | 2020 | |||

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 26,440 | 33,135 | 9892 | 14,000 | 16,548 | 19,135 | 67.89 | 96.09 | 113.58 | 131.33 | 42% | 16% |

| Diabetes Mellitus and Endocrine Disorders | 4037 | 10,850 | 575 | 768 | 3462 | 10,082 | 3.95 | 5.27 | 23.76 | 69.20 | 34% | 191% |

| Digestive Diseases | 4931 | 3796 | 2941 | 2103 | 1990 | 1693 | 20.19 | 14.43 | 13.66 | 11.62 | −28% | −15% |

| Genitourinary Diseases | 2360 | 4834 | 1133 | 2525 | 1227 | 2309 | 7.78 | 17.33 | 8.42 | 15.85 | 123% | 88% |

| Malignant Neoplasms | 8714 | 14,752 | 2802 | 4870 | 5912 | 9882 | 19.23 | 33.42 | 40.58 | 67.82 | 74% | 67% |

| Respiratory Diseases | 7915 | 11,163 | 3363 | 6275 | 4552 | 4888 | 23.08 | 43.07 | 31.24 | 33.55 | 87% | 7% |

| Other | 10,636 | 10,966 | 379 | 1054 | 10,257 | 9912 | 2.60 | 7.23 | 70.40 | 68.03 | 178% | −3% |

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240047761 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Singh Thakur, J.; Nangia, R.; Singh, S. Progress and challenges in achieving noncommunicable diseases targets for the sustainable development goals. FASEB BioAdvances 2021, 3, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mortality Data Base. Available online: https://platform.who.int/mortality/themes/theme-details/MDB/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564854 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. The National Policy and Strategic Framework for Prevention and Control of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. 2010. Available online: https://www.health.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/13_NCD.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. Guideline for the Establishment of HLCs [Internet]. 2011. p. 2. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/ncdccs/Data/LKA_B3_Guideline%20for%20the%20establishment%20of%20HLCs.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Herath, T.; Perera, M.; Kasturiratne, A. Factors influencing the decision to use state-funded healthy lifestyle centres in a low-income setting: A qualitative study from Sri Lanka. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. Reorganising Primary Health Care in Sri Lanka, Preserving Our Progress, Preparing for Our Future. 2018. Available online: https://www.pssp.health.gov.lk/images/pdf/01-18-2019-eng.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. Annual Health Bulletin. 2019. Available online: https://www.health.gov.lk/annual-health-bulletin/ (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Ramanayake, R.P.J.C.; Perera, D.P.; Jayasinghe, J.A.P.H.; Munasinghe, M.M.E.M.; de Soyza, E.C.E.S.; Jayawardana, M.A.V.S. Public sector primary care services in Sri Lanka and the specialist family physician: A qualitative study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 6830–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ediriweera, D.S.; Karunapema, P.; Pathmeswaran, A.; Arnold, M. Increase in premature mortality due to non-communicable diseases in Sri Lanka during the first decade of the twenty-first century. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Census and Statistics Sri Lanka. Vital Statistics. Available online: http://www.statistics.gov.lk/Population/StaticalInformation/VitalStatistics/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Cancer Incidence Data 2009. National Cancer Control Program: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2015. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/cancer-incidence-data-sri-lanka-2009#:~:text=Cancer%20Incidence%20Data%3A%20Sri%20Lanka%202009.%20Colombo%2C%20Sri,Control%20Programme%2C%20Ministry%20of%20Health%20%28Sri%20Lanka%29%2C%202015 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Munasinghe, H.; Wijekoon, S.; Dissanayaka, P.; Jayasundara, D.; Piyasena, P.M.; Sivaprasad, S.; Nugawela, M.D. Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Microvascular Complications in Sri Lanka: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2025, 17, e95630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannan-Eliya, R.P.; Wijemunige, N.; Perera, P.; Kapuge, Y.; Gunawardana, N.; Sigera, C.; Jayatissa, R.; Herath, H.M.M.; Gamage, A.; Weerawardena, N.; et al. Prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes in Sri Lanka: A new global hotspot-estimates from the Sri Lanka Health and Ageing Survey 2018/2019. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2023, 11, e003160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeyrathna, P.; Weerasinghe, M.; Agampodi, S.B.; Samaranayake, S.; Pushpakumara, P.H.G.J. Evaluating spatial access to primary care and health disparities in a rural district of Sri Lanka: Implications for strategic health policy interventions. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0005192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidanapathirana, J. Reaching equal health in Sri Lanka: A gender perspective. Asian J. Interdiscip. Res. 2021, 4, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Tomson, G.; Petzold, M.; Kabir, Z.N. Socioeconomic status overrides age and gender in determining health-seeking behaviour in rural Bangladesh. Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, B.T.; Hatcher, J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: Challenging the policy makers. J. Public Health 2005, 27, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Death Rate in 2004 (per 100,000) | Death Rate in 2020 (per 100,000) | Percentage Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 181.5 | 227.4 | 25% |

| Respiratory Diseases | 54.3 | 76.6 | 41% |

| Digestive Diseases | 33.8 | 26.1 | −23% |

| Malignant Neoplasms | 59.8 | 101.2 | 69% |

| Genitourinary Diseases | 16.2 | 33.1 | 105% |

| Diabetes Mellitus and Endocrine Disorders | 27.7 | 74.5 | 169% |

| Other | 73.0 | 75.3 | 3% |

| Disease | Death Rate in 2004 (per 100,000) | Death Rate in 2020 (per 100,000) | Percentage Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 67.8 | 96.1 | 42% |

| Respiratory Diseases | 23.1 | 43.1 | 87% |

| Digestive Diseases | 20.2 | 14.4 | −28% |

| Malignant Neoplasms | 19.2 | 33.4 | 74% |

| Genitourinary Diseases | 7.7 | 17.3 | 123% |

| Diabetes Mellitus and Endocrine Disorders | 3.9 | 5.2 | 34% |

| Other | 2.6 | 7.2 | 178% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Munasinghe, H.; Dissanayaka, P.; Jayasundara, M.; Piyasena, M.P.; Sivaprasad, S.; Nugawela, M.D. Trends in Mortality from Diabetes and Other Non-Communicable Diseases Among Sri Lankan Adults: A Retrospective Population-Based Study, 2004–2020/2021. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238568

Munasinghe H, Dissanayaka P, Jayasundara M, Piyasena MP, Sivaprasad S, Nugawela MD. Trends in Mortality from Diabetes and Other Non-Communicable Diseases Among Sri Lankan Adults: A Retrospective Population-Based Study, 2004–2020/2021. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238568

Chicago/Turabian StyleMunasinghe, Harshana, Pansujee Dissanayaka, Mangalika Jayasundara, Mapa Prabhath Piyasena, Sobha Sivaprasad, and Manjula D. Nugawela. 2025. "Trends in Mortality from Diabetes and Other Non-Communicable Diseases Among Sri Lankan Adults: A Retrospective Population-Based Study, 2004–2020/2021" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238568

APA StyleMunasinghe, H., Dissanayaka, P., Jayasundara, M., Piyasena, M. P., Sivaprasad, S., & Nugawela, M. D. (2025). Trends in Mortality from Diabetes and Other Non-Communicable Diseases Among Sri Lankan Adults: A Retrospective Population-Based Study, 2004–2020/2021. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238568