Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Early Left Ventricular Function After STEMI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

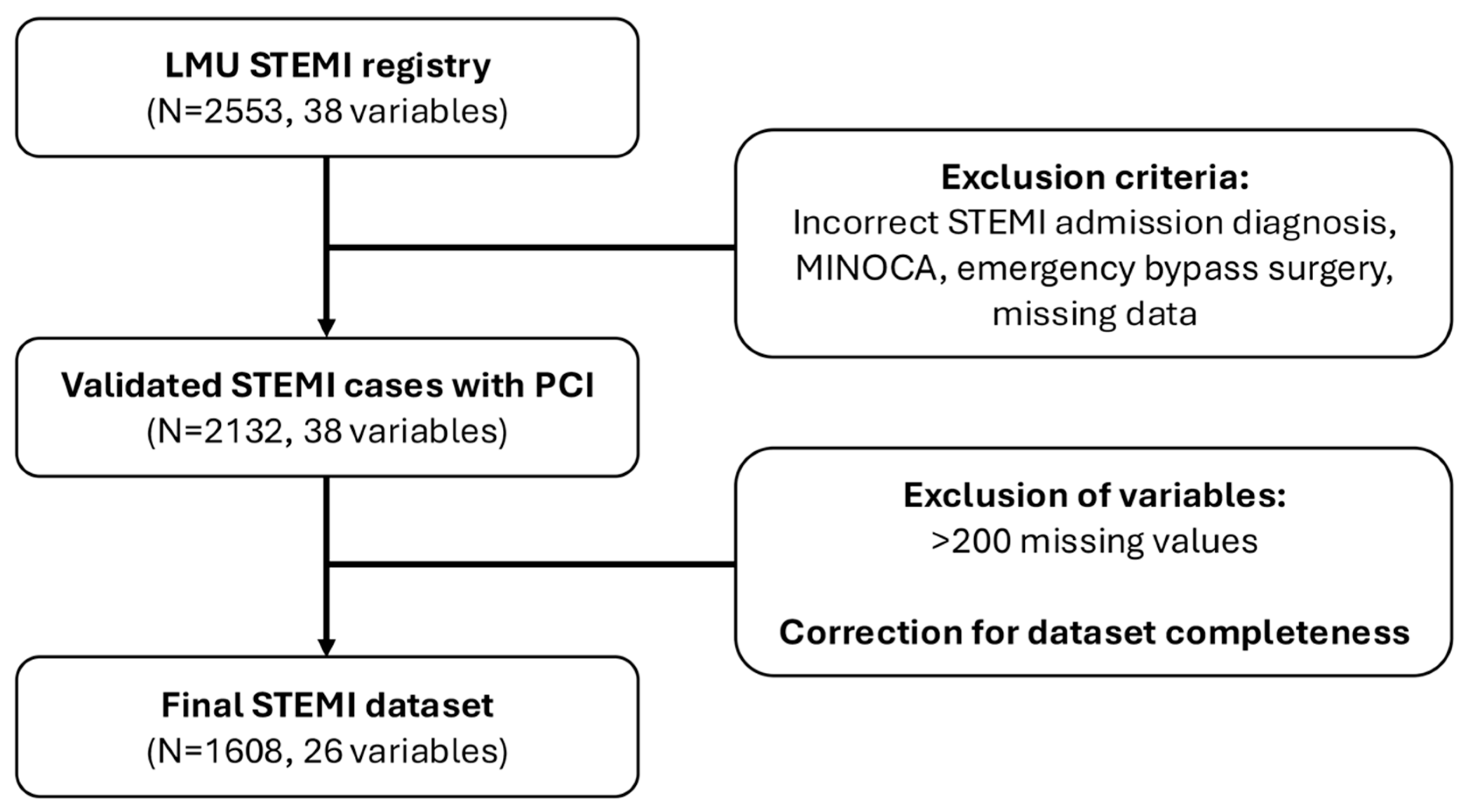

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Ventricular Function

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Model Development

- Decision Trees: partition the feature space recursively to minimize variance within subgroups [31].

- Random Forests: ensemble of Decision Trees built on bootstrapped samples with feature subsampling to reduce variance and overfitting [29].

- XGBoost: sequentially adds trees to correct residual errors, with gradient-based optimization and regularization to control model complexity [28].

2.7. Model Evaluation

2.8. Explainability

2.9. Statistical Analysis

2.10. Software

3. Results

3.1. Data Basis

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

3.3. Hemodynamics and Shock

3.4. Laboratory Indicators of Infarction Size

3.5. Mortality

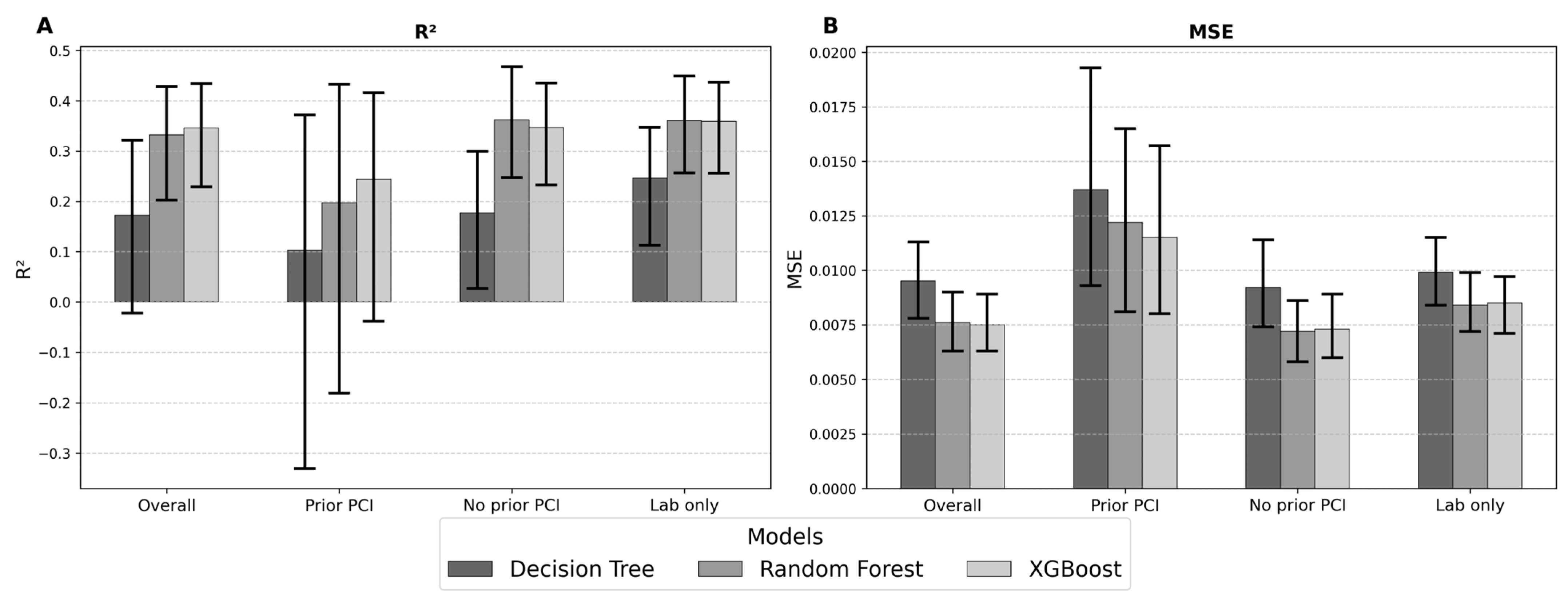

3.6. Model Performance in Prediction of LV Function

3.7. Categorical Analysis of LV Function

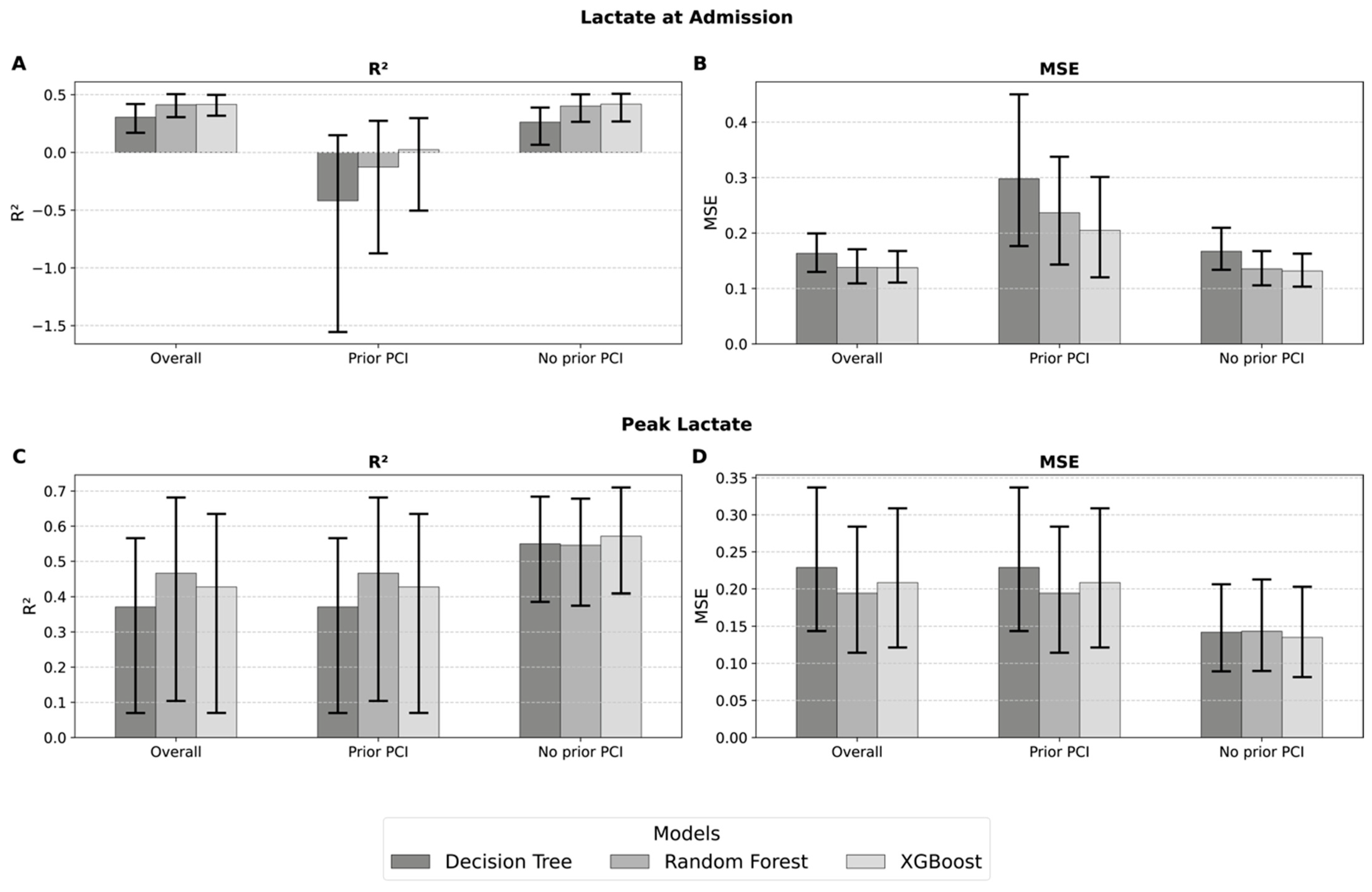

3.8. Lactate Values as a Surrogate for LV Function

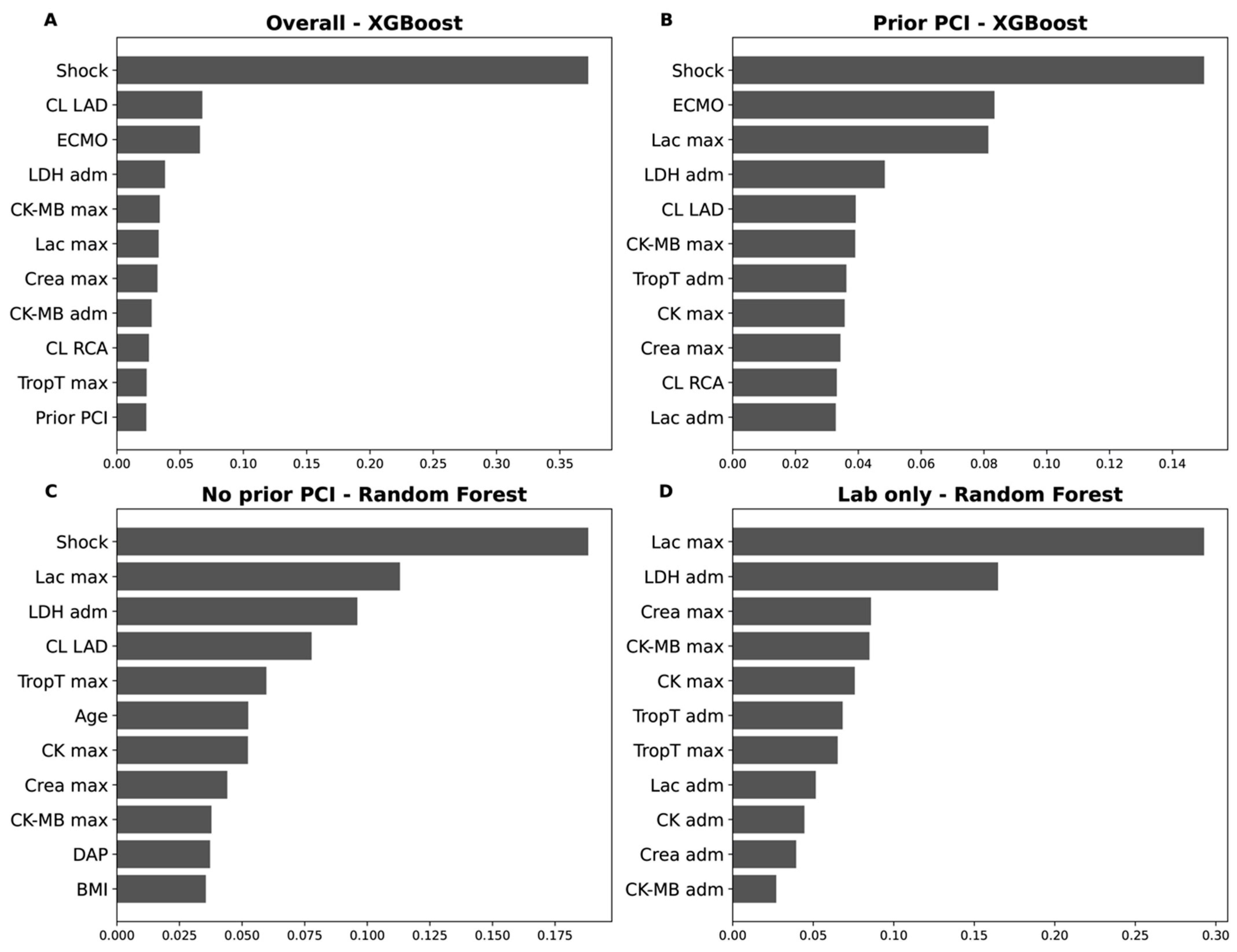

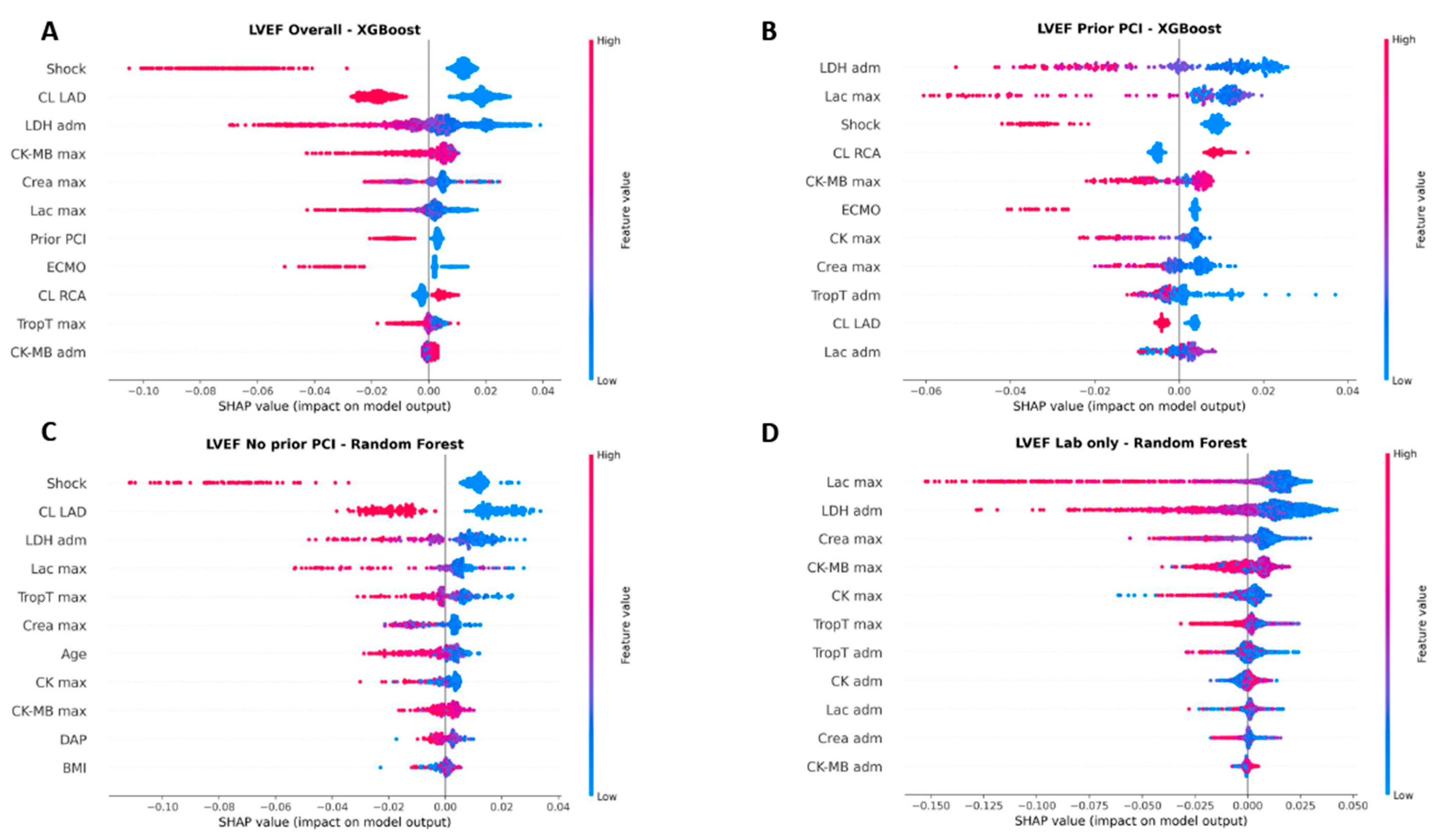

3.9. Feature Importance

3.10. Independent Validation

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AST | Aspartate transaminase |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CAV | Contrast agent volume |

| CK | Creatine kinase |

| CK-MB | Creatine kinase-myocardial band |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DAP | Dose area product |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| EVS | Explained variance score |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IABP | Intra-aortic balloon pump |

| ICD | Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| LAD | Left anterior descending coronary artery |

| LCA | Left main coronary artery |

| LCX | Left circumflex coronary artery |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LV | Left ventricle / left ventricular |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

| MCS | Mechanical circulatory support |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| MINOCA | Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares Regression |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PR-AUC | Precision–recall area under the curve |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| RCA | Right coronary artery |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root mean squared error |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SHAP | Shapley additive explanations |

| STEMI | ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| XG | Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) |

References

- WHO. Global Health Estimates: Leading Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodesh, A.; Loebl, N.; de Filippo, O.; Orvin, K.; Levi, A.; Bental, T.; Kornowski, R.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Perl, L. Machine-learning based calculator for personalized risk assessment following ST-elevation myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felbel, D.; Fackler, S.; Michalke, R.; Paukovitsch, M.; Groger, M.; Kessler, M.; Nita, N.; Teumer, Y.; Schneider, L.; Imhof, A.; et al. Prolonged pain-to-balloon time still impairs midterm left ventricular function following STEMI. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, K.A.; Adnan, F.; Ahmed, O.; Yaqeen, S.R.; Ali, J.; Irfan, M.; Edhi, M.M.; Hashmi, A.A. Risk Assessment of Patients After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction by Killip Classification: An Institutional Experience. Cureus 2020, 12, e12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, T.; Hartman, M.H.T.; Vlaar, P.J.J.; Prakken, N.H.J.; van der Ende, Y.M.Y.; Lexis, C.P.H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; van der Horst, I.C.C.; Lipsic, E.; Nijveldt, R.; et al. Predictors of left ventricular remodeling after ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 33, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegiel, M.; Rakowski, T. Circulating biomarkers as predictors of left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Postep. Kardiol. Interwencyjnej 2021, 17, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyhonen, P.; Kylmala, M.; Vesterinen, P.; Kivisto, S.; Holmstrom, M.; Lauerma, K.; Vaananen, H.; Toivonen, L.; Hanninen, H. Peak CK-MB has a strong association with chronic scar size and wall motion abnormalities after revascularized non-transmural myocardial infarction—A prospective CMR study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2018, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babuin, L.; Jaffe, A.S. Troponin: The biomarker of choice for the detection of cardiac injury. CMAJ 2005, 173, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younger, J.F.; Plein, S.; Barth, J.; Ridgway, J.P.; Ball, S.G.; Greenwood, J.P. Troponin-I concentration 72 h after myocardial infarction correlates with infarct size and presence of microvascular obstruction. Heart 2007, 93, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, S.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Peng, N.; Tang, Y. A nomogramic model for predicting the left ventricular ejection fraction of STEMI patients after thrombolysis-transfer PCI. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1178417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinstadler, S.J.; Feistritzer, H.J.; Reindl, M.; Klug, G.; Mayr, A.; Mair, J.; Jaschke, W.; Metzler, B. Combined biomarker testing for the prediction of left ventricular remodelling in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Open Heart 2016, 3, e000485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, V.; Bayat, F.; Asadzadeh, B.; Saffarian, E.; Gheymati, A.; Mahmoudi, E.; Movahed, M.R. Early prediction of ventricular functional recovery after myocardial infarction by longitudinal strain study. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 11, 471–477. [Google Scholar]

- Virbickiene, A.; Lapinskas, T.; Garlichs, C.D.; Mattecka, S.; Tanacli, R.; Ries, W.; Torzewski, J.; Heigl, F.; Pfluecke, C.; Darius, H.; et al. Imaging Predictors of Left Ventricular Functional Recovery after Reperfusion Therapy of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Assessed by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiron, V.; George, P.V. Correlation of cumulative ST elevation with left ventricular ejection fraction and 30-day outcome in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. J. Postgrad. Med. 2019, 65, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathbout, M.; Asfour, A.; Leung, S.; Lolay, G.; Idris, A.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Ziada, K.M. NT-proBNP Level Predicts Extent of Myonecrosis and Clinical Adverse Outcomes in Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Pilot Study. Med. Res. Arch. 2020, 8, 10-18103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jering, K.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Granger, C.B.; Kober, L.; Lewis, E.F.; Maggioni, A.P.; Mann, D.L.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Prescott, M.F.; et al. Prognostic Importance of NT-proBNP (N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide) Following High-Risk Myocardial Infarction in the PARADISE-MI Trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 2023, 16, e010259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, J.J.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Slingerland, R.J.; Kolkman, J.J.; Suryapranata, H.; Hoorntje, J.C.; Dambrink, J.H.; Gosselink, A.T.; de Boer, M.J.; Zijlstra, F.; et al. Comparison of usefulness of C-reactive protein versus white blood cell count to predict outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST elevation myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 101, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaverbeke, M.; Veltman, D.; Pattyn, N.; De Crem, N.; Gillijns, H.; Cornelissen, V.; Janssens, S.; Sinnaeve, P.R. C-reactive protein during and after myocardial infarction in relation to cardiac injury and left ventricular function at follow-up. Clin. Cardiol. 2018, 41, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, J.P.; Lueneberg, M.E.; da Silva, R.L.; Fattah, T.; Gottschall, C.A.M.; Moreira, D.M. Correlation between leukocyte count and infarct size in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Arch. Med. Sci. Atheroscler. Dis. 2016, 1, e44–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Lian, S.; Ruan, Q.; Qu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chai, D.; Lin, X. Predicting the risk of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction using an interpretable machine learning model. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1444323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.H.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, S.; Jang, J.H.; Jo, Y.Y.; Son, J.M.; Lee, M.S.; Kwon, J.M.; Kwun, J.S.; Cho, H.W.; et al. AI-enabled ECG index for predicting left ventricular dysfunction in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, A.; Li, K.; Yan, L.L.; Chandramouli, C.; Hu, R.; Jin, X.; Li, P.; Chen, M.; Qian, G.; Chen, Y. Machine learning-based prediction of infarct size in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A multi-center study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 375, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritharan, H.P.; Nguyen, H.; Ciofani, J.; Bhindi, R.; Allahwala, U.K. Machine-learning based risk prediction of in-hospital outcomes following STEMI: The STEMI-ML score. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1454321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; Van Der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. pandas: A foundational Python library for data analysis and statistics. Python High Perform. Sci. Comput. 2011, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; Volume 445, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeri, C.; Valente, S.; Chiostri, M.; Gensini, G.F. Clinical significance of lactate in acute cardiac patients. World J. Cardiol. 2015, 7, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.H.; Cho, H.K.; Oh, J.H.; Chun, W.J.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, M.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, K.H.; Kim, J.; Song, Y.B.; et al. Clinical Significance of Serum Lactate in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, N.; Sun, T.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, C. Association between normalized lactate load and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 399, 131658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuernau, G.; Desch, S.; de Waha-Thiele, S.; Eitel, I.; Neumann, F.J.; Hennersdorf, M.; Felix, S.B.; Fach, A.; Bohm, M.; Poss, J.; et al. Arterial Lactate in Cardiogenic Shock: Prognostic Value of Clearance Versus Single Values. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 2208–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbach, J.A.; Di Santo, P.; Kapur, N.K.; Thayer, K.L.; Simard, T.; Jung, R.G.; Parlow, S.; Abdel-Razek, O.; Fernando, S.M.; Labinaz, M.; et al. Lactate Clearance as a Surrogate for Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock: Insights From the DOREMI Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsztajn, L.; Oyallon, E.; Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on typical tabular data? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 507–520. [Google Scholar]

- Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Armon, A. Tabular data: Deep learning is not all you need. Inf. Fusion 2022, 81, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathi, R.; Pavithra, S.; Pattabiraman, V. Deep Learning Approach on Multimodal Data for Myocardial Infarction Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Network Systems (CINS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 28–29 November 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, J.T.; Weston Hughes, J.; Sanchez, P.A.; Perez, M.; Ouyang, D.; Ashley, E.A. Multimodal deep learning enhances diagnostic precision in left ventricular hypertrophy. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2022, 3, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokodi, M.; Magyar, B.; Soos, A.; Takeuchi, M.; Tolvaj, M.; Lakatos, B.K.; Kitano, T.; Nabeshima, Y.; Fabian, A.; Szigeti, M.B.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Right Ventricular Ejection Fraction Using 2D Echocardiograms. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, A.; Prajapati, R.; El-Wakeel, A.; Adjeroh, D.; Patel, B.; Gyawali, P. AI analysis for ejection fraction estimation from 12-lead ECG. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Li, Y.M.; Wang, J.Y.; Jia, Y.H.; Yi, Z.; Chen, M. Utilizing multimodal artificial intelligence to advance cardiovascular diseases. Precis. Clin. Med. 2025, 8, pbaf016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, R.; Oikonomou, E.K.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Morley, J.R.; Wiens, J.; Butte, A.J.; Topol, E.J. Transforming Cardiovascular Care With Artificial Intelligence: From Discovery to Practice: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersosimo, A.; Zito, E.; Pierucci, N.; Matteucci, A.; La Fazia, V.M. A Talk with ChatGPT: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Shaping the Future of Cardiology and Electrophysiology. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, G.D.; Dhutia, N.M.; Shun-Shin, M.J.; Willson, K.; Harrison, J.; Raphael, C.E.; Zolgharni, M.; Mayet, J.; Francis, D.P. Defining the real-world reproducibility of visual grading of left ventricular function and visual estimation of left ventricular ejection fraction: Impact of image quality, experience and accreditation. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 31, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akil, S.; Castaings, J.; Thind, P.; Ahlfeldt, T.; Akhtar, M.; Gonon, A.T.; Quintana, M.; Bouma, K. Impact of experience on visual and Simpson’s biplane echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2025, 45, e12918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavendiranathan, P.; Popovic, Z.B.; Flamm, S.D.; Dahiya, A.; Grimm, R.A.; Marwick, T.H. Improved interobserver variability and accuracy of echocardiographic visual left ventricular ejection fraction assessment through a self-directed learning program using cardiac magnetic resonance images. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2013, 26, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N = 1608) | Prior PCI (N = 325) | No Prior PCI (N = 1283) | p Value | Corrected p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age [years] | 64.8 (±13.5) | 68.8 (±12.9) | 63.8 (±13.4) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 27.2 (±4.4) | 27.7 (±4.6) | 27.1 (±4.4) | 0.0123 * | 0.0267 * |

| Sex (female) [N (%)] | 404 (25.1%) | 78 (24.0%) | 326 (25.4%) | 0.6008 | 0.6759 |

| Coronary perfusion type | |||||

| Right [N (%)] | 1401 (87.1%) | 289 (88.9%) | 1112 (86.7%) | 0.2790 | 0.3720 |

| Left [N (%)] | 123 (7.7%) | 20 (6.2%) | 103 (8.0%) | 0.2562 | 0.3720 |

| Balanced [N (%)] | 84 (5.2%) | 16 (4.9%) | 68 (5.3%) | 0.7850 | 0.8312 |

| Coronary artery disease | |||||

| 1 vessel [N (%)] | 497 (30.9%) | 42 (12.9%) | 455 (35.5%) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| 2 vessels [N (%)] | 447 (27.8%) | 75 (23.1%) | 372 (29.0%) | 0.0334 * | 0.0668 |

| 3 vessels [N (%)] | 664 (41.3%) | 208 (64.0%) | 456 (35.5%) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| Culprit lesion | |||||

| LCA [N (%)] | 21 (1.3%) | 7 (2.2%) | 14 (1.1%) | 0.1317 | 0.2163 |

| LAD [N (%)] | 818 (50.9%) | 159 (48.9%) | 659 (51.4%) | 0.4317 | 0.4317 |

| LCX [N (%)] | 176 (11.0%) | 36 (11.1%) | 140 (10.9%) | 0.9322 | 0.9322 |

| RCA [N (%)] | 592 (36.8%) | 122 (37.5%) | 470 (36.6%) | 0.7624 | 0.8312 |

| Procedural data | |||||

| CAV [ml] | 206.97 (±98.37) | 188.46 (±94.29) | 211.66 (±98.86) | 0.0002 * | 0.0006 * |

| Radiation time [min] | 14.09 (±11.69) | 14.59 (±12.98) | 13.97 (±11.35) | 0.5405 | 0.6277 |

| DAP [cGy/cm2] | 4306 (±4111) | 4210 (±3621) | 4331 (±4227) | 0.3971 | 0.5106 |

| Tirofiban [N (%)] | 160 (10.0%) | 54 (16.6%) | 106 (8.3%) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| Hemodynamics and shock | |||||

| Shock [N (%)] | 264 (16.4%) | 73 (22.5%) | 191 (14.9%) | 0.0010 * | 0.0026 * |

| CPR [N (%)] | 222 (13.8%) | 51 (15.7%) | 171 (13.3%) | 0.2698 | 0.3720 |

| ECMO [N (%)] | 76 (4.7%) | 27 (8.3%) | 49 (3.8%) | 0.0007 * | 0.0019 * |

| Impella [N (%)] | 15 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | 14 (1.1%) | 0.1894 | 0.2965 |

| ECMO + Impella [N (%)] | 4 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (0.2%) | 0.8113 | 0.8345 |

| IABP [N (%)] | 5 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.4%) | 0.2597 | 0.3720 |

| LVEF discharge [%] | 49 (±11) | 47 (±12) | 50 (±10) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| Exitus [N (%)] | 106 (6.59%) | 32 (13.68%) | 74 (5.39%) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| Laboratory values | |||||

| CK adm [U/L] | 874.7(±1501.6) | 818.2 (±1685.2) | 889.0 (±1451.8) | 0.0001 * | 0.0003 * |

| CK max [U/L] | 2348.2 (±3726.7) | 2296.4 (±4020.9) | 2361.3 (±3649.9) | 0.0126 * | 0.0267 * |

| CK-MB adm [U/L] | 102.1 (±162.9) | 86.1 (±172.2) | 106.2 (±160.3) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| CK-MB max [U/L] | 234.3 (±251.9) | 206.9 (±238.6) | 241.2 (±254.8) | 0.0011 * | 0.0026 * |

| Trop T adm [ng/mL] | 3.41 (±10.35) | 3.08 (±10.64) | 3.50 (±10.27) | 0.0001 * | 0.0003 * |

| Trop T max [ng/mL] | 9.09 (±15.02) | 9.25 (±16.15) | 9.04 (±14.73) | 0.0589 | 0.1116 |

| Crea adm [mg/dL] | 1.13 (±0.62) | 1.36 (±1.00) | 1.07 (±0.46) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| Crea max [mg/dL] | 1.35 (±0.90) | 1.65 (±1.32) | 1.27 (±0.73) | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * |

| LDH adm [U/L] | 421.43 (±653.40) | 456.82 (±760.56) | 412.47 (±623.36) | 0.1127 | 0.2029 |

| Lactate adm [mmol/L] | 2.48 (±2.47) | 2.65 (±2.54) | 2.44 (±2.45) | 0.5278 | 0.6277 |

| Lactate max [mmol/L] | 3.49 (±3.80) | 3.96 (±4.10) | 3.37 (±3.71) | 0.1322 | 0.2163 |

| MSE | RMSE | MAE | R2 | EVS | MAPE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Cohort | OLS | 0.0078 (0.0064, 0.0090) | 0.0881 (0.0803, 0.0950) | 0.0686 (0.0619, 0.0950) | 0.3202 (0.1821, 0.4354) | 0.3202 (0.1915, 0.4394) | 17.92% (15.89%, 20.02%) |

| OLS + L1 | 0.0077 (0.0065, 0.0089) | 0.0877 (0.0808, 0.0945) | 0.0686 (0.0629, 0.0747) | 0.3263 (0.1977, 0.4226) | 0.3310 (0.2085, 0.4243) | 17.08% (14.99%, 19.48%) | |

| OLS + L2 | 0.0076 (0.0065, 0.0090) | 0.0873 (0.0809, 0.094) | 0.0686 (0.0633, 0.0751) | 0.3324 (0.2033, 0.4371) | 0.3379 (0.2145, 0.4406) | 17.02% (15.11%, 19.44%) | |

| DT | 0.0095 (0.0078, 0.0113) | 0.0972 (0.0882, 0.1064) | 0.0754 (0.0688, 0.0826) | 0.1721 (-0.0224, 0.3213) | 0.1837 (0.0063, 0.3289) | 17.72% (15.27%, 20.51%) | |

| RF | 0.0076 (0.0063, 0.0090) | 0.0873 (0.0795, 0.0950) | 0.0673 (0.0614, 0.0734) | 0.3326 (0.2025, 0.4286) | 0.3402 (0.2171, 0.4368) | 16.11% (13.64%, 18.96%) | |

| XG | 0.0075 (0.0063, 0.0089) | 0.0864 (0.0793, 0.0942) | 0.0677 (0.0620, 0.0740) | 0.3461 (0.2289, 0.4346) | 0.3542 (0.2427, 0.4414) | 16.11% (13.89%, 18.81%) | |

| Prior PCI | OLS | 0.0144 (0.0096, 0.0173) | 0.1202 (0.0980, 0.1315) | 0.0953 (0.0779, 0.1057) | 0.1870 (−0.1179, 0.3925) | 0.1896 (−0.0894, 0.3989) | 24.45% (18.24%, 30.43%) |

| OLS + L1 | 0.0121 (0.0081, 0.0161) | 0.1101 (0.0900, 0.1269) | 0.0875 (0.0716, 0.1008) | 0.2206 (−0.0787, 0.4049) | 0.2213 (−0.0702, 0.4175) | 26.09% (19.78%, 33.43%) | |

| OLS + L2 | 0.0121 (0.0081, 0.0160) | 0.1098 (0.0900, 0.1265) | 0.0878 (0.0719, 0.1011) | 0.2097 (−0.0839, 0.3823) | 0.2116 (−0.0612, 0.3988) | 26.70% (20.49%, 34.19%) | |

| DT | 0.0137 (0.0093, 0.0193) | 0.1169 (0.0963, 0.1390) | 0.0923 (0.0767, 0.1102) | 0.1028 (−0.3303, 0.3722) | 0.1028 (−0.2943, 0.3828) | 24.43% (18.69%, 30.68%) | |

| RF | 0.0122 (0.0081, 0.0165) | 0.1106 (0.0901, 0.1283) | 0.0882 (0.0723, 0.1043) | 0.1969 (−0.1805, 0.4322) | 0.1971 (−0.1578, 0.4387) | 22.81% (17.53%, 28.60%) | |

| XG | 0.0115 (0.0080, 0.0157) | 0.1073 (0.0896, 0.1253) | 0.0850 (0.0698, 0.1015) | 0.2442 (−0.0385, 0.4156) | 0.2443 (−0.0135, 0.4229) | 22.85% (16.82%, 29.78%) | |

| No Prior PCI | OLS | 0.0073 (0.0058, 0.0087) | 0.0855 (0.0762, 0.0933) | 0.0675 (0.0605, 0.0741) | 0.3351 (0.2134, 0.4461) | 0.3399 (0.2189, 0.4502) | 16.27% (14.00%, 18.89%) |

| OLS + L1 | 0.0073 (0.0061, 0.0085) | 0.0854 (0.0781, 0.0922) | 0.0679 (0.0621, 0.07327) | 0.3390 (0.2203, 0.4391) | 0.3435 (0.2245, 0.4408) | 16.24% (14.23%, 17.42%) | |

| OLS + L2 | 0.0072 (0.0058, 0.0086) | 0.0849 (0.0762, 0.0927) | 0.0673 (0.0604, 0.0735) | 0.3421 (0.2307, 0.4365) | 0.3456 (0.2379, 0.4365) | 16.46% (13.42%, 17.78%) | |

| DT | 0.0092 (0.0074, 0.0114) | 0.0961 (0.0862, 0.1068) | 0.0756 (0.0684, 0.0832) | 0.1766 (0.0270, 0.2993) | 0.1795 (0.0286, 0.3001) | 18.17% (15.67%, 20.89%) | |

| RF | 0.0072 (0.0058, 0.0086) | 0.0846 (0.0761, 0.0930) | 0.0664 (0.0604, 0.0727) | 0.3622 (0.2470, 0.4678) | 0.3627 (0.2498, 0.4707) | 15.64% (13.61%, 17.95%) | |

| XG | 0.0073 (0.0060, 0.0089) | 0.0856 (0.0775, 0.0943) | 0.0667 (0.0606, 0.0730) | 0.3464 (0.2326, 0.4349) | 0.3474 (0.2349, 0.4404) | 15.79% (13.72%, 18.15%) | |

| Laboratory Values Only | OLS | 0.0088 (0.0076, 0.0101) | 0.0938 (0.0873, 0.1003) | 0.0760 (0.0707, 0.0819) | 0.3328 (0.2322, 0.4105) | 0.03345 (0.2402, 0.4139) | 18.58% (16.34%, 20.98%) |

| OLS + L1 | 0.0088 (0.0076, 0.0102) | 0.0939 (0.0871, 0.1010) | 0.0762 (0.0705, 0.0825) | 0.3313 (0.2359, 0.4163) | 0.3330 (0.2398, 0.4168) | 18.65% (16.30%, 21.30%) | |

| OLS + L2 | 0.0088 (0.0076, 0.0100) | 0.0938 (0.0869, 0.1001) | 0.0761 (0.0706, 0.0818) | 0.3328 (0.2312, 0.4135) | 0.3346 (0.2387, 0.4181) | 18.72% (16.21%, 21.09%) | |

| DT | 0.0099 (0.0084, 0.0115) | 0.0997 (0.0919, 0.1074) | 0.0797 (0.0738, 0.0861) | 0.2464 (0.1127, 0.3464) | 0.2470 (0.1154, 0.3477) | 19.68% (17.37%, 22.23%) | |

| RF | 0.0084 (0.0072, 0.0099) | 0.0918 (0.0850, 0.0994) | 0.0741 (0.0686, 0.0803) | 0.3604 (0.2564, 0.4492) | 0.3618 (0.2624, 0.4496) | 18.01% (15.83%, 20.43%) | |

| XG | 0.0085 (0.0071, 0.0097) | 0.0919 (0.0844, 0.0987) | 0.0738 (0.0680, 0.0797) | 0.3588 (0.2559, 0.4362) | 0.3594 (0.2622, 0.4387) | 18.23% (15.74%, 20.51%) |

| AUC | PR-AUC | F1 | AUC | PR-AUC | F1 | AUC | PR-AUC | F1 | AUC | PR-AUC | F1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Cohort | LR | 0.53 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.48 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.62 |

| DT | 0.53 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.61 | |

| RF | 0.53 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.46 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.60 | |

| XG | 0.52 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.60 | |

| Prior PCI | LR | 0.57 | 0.90 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

| DT | 0.62 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.63 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.43 | 0.49 | |

| RF | 0.62 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.62 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.40 | |

| XG | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.38 | |

| No Prior PCI | LR | 0.44 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.37 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.65 |

| DT | 0.50 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.52 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.63 | |

| RF | 0.52 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.66 | |

| XG | 0.41 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.61 | |

| Laboratory Values Only | LR | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.53 |

| DT | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 089 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.57 | |

| RF | 0.76 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.55 | |

| XG | 0.74 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.50 | |

| Method | MSE | RMSE | MAE | R2 | EVS | MAPE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Cohort | XGBoost (model development) | 0.0075 (0.0063, 0.0089) | 0.0864 (0.0793, 0.0942) | 0.0677 (0.0620, 0.0740) | 0.3461 (0.2289, 0.4346) | 0.3542 (0.2427, 0.4414) | 16.11% (13.89%, 18.81%) |

| Validation cohort | 0.0080 | 0.0894 | 0.0791 | 0.3437 | 0.3660 | 18.48% | |

| Prior PCI | XGBoost (model development) | 0.0115 (0.0080, 0.0157) | 0.1073 (0.0896, 0.1253) | 0.0850 (0.0698, 0.1015) | 0.2442 (−0.0385, 0.4156) | 0.2443 (−0.0135, 0.4229) | 22.85% (16.82%, 29.78%) |

| Validation cohort | 0.0098 | 0.0988 | 0.0759 | −0.5626 | 0.3594 | 22.55% | |

| No Prior PCI | Random Forest (model development) | 0.0072 (0.0058, 0.0086) | 0.0846 (0.0761, 0.0930) | 0.0664 (0.0604, 0.0727) | 0.3622 (0.2470, 0.4678) | 0.3627 (0.2498, 0.4707) | 15.64% (13.61%, 17.95%) |

| Validation cohort | 0.0090 | 0.0948 | 0.0757 | 0.2933 | 0.2956 | 18.62% | |

| Laboratory Values Only | Random Forest (model development) | 0.0084 (0.0072, 0.0099) | 0.0918 (0.0850, 0.0994) | 0.0741 (0.0686, 0.0803) | 0.3604 (0.2564, 0.4492) | 0.3618 (0.2624, 0.4496) | 18.01% (15.83%, 20.43%) |

| Validation cohort | 0.0091 | 0.0955 | 0.0852 | 0.2522 | 0.2570 | 20.18% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, S.-F.; Diegruber, K.; Esser, D.; Vieluf, S.; Stremmel, C. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Early Left Ventricular Function After STEMI. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238563

Zheng S-F, Diegruber K, Esser D, Vieluf S, Stremmel C. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Early Left Ventricular Function After STEMI. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238563

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Shunjie-Fabian, Kathrin Diegruber, David Esser, Solveig Vieluf, and Christopher Stremmel. 2025. "Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Early Left Ventricular Function After STEMI" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238563

APA StyleZheng, S.-F., Diegruber, K., Esser, D., Vieluf, S., & Stremmel, C. (2025). Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Early Left Ventricular Function After STEMI. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238563