Chair-Based Magnetic Pelvic Floor Stimulation and Female Sexual Function in Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

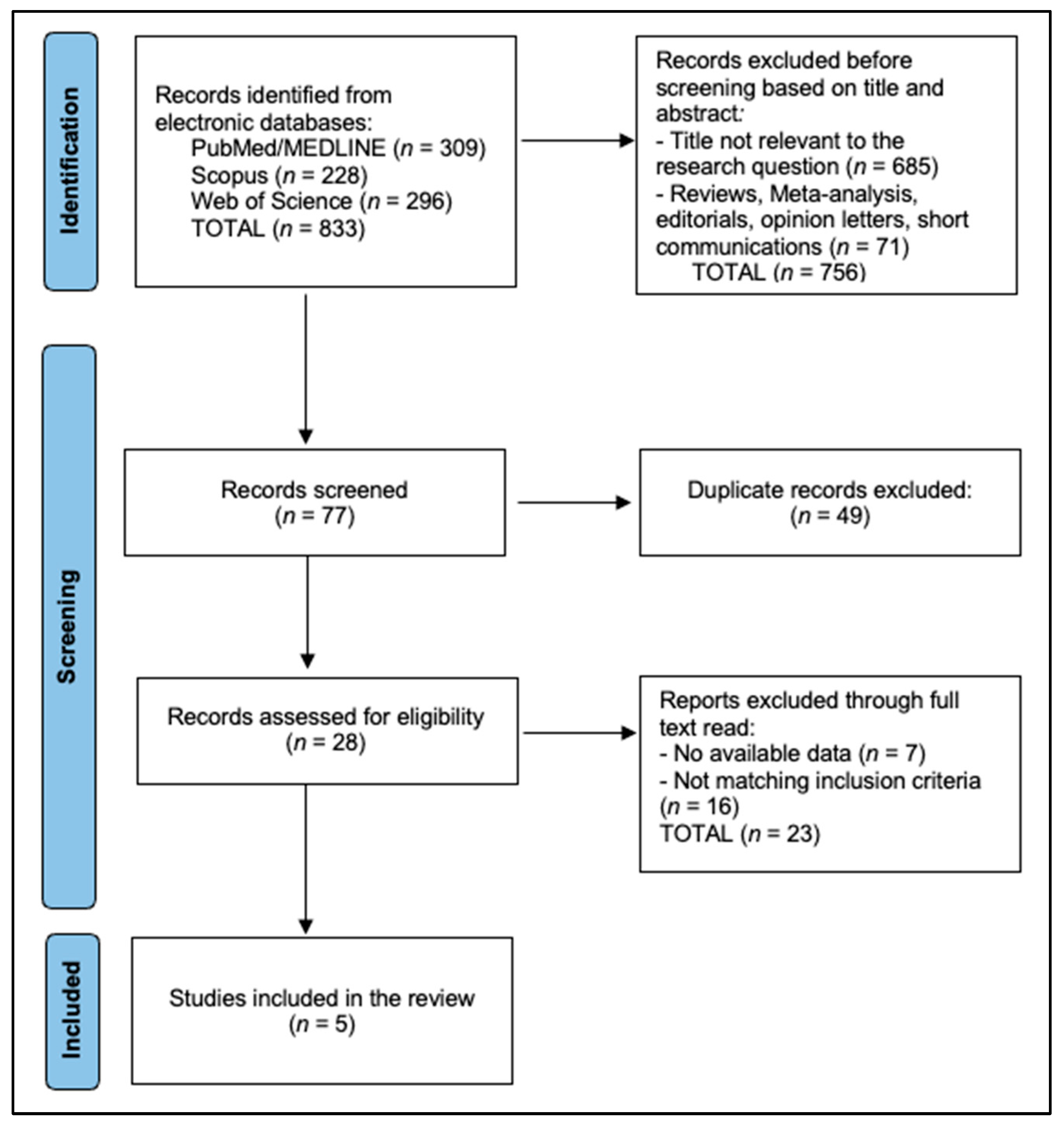

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol, Registration, and Eligibility

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategies

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Quantitative Synthesis

2.6. Risk of Bias and Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chu, C.M.; Arya, L.A.; Andy, U.U. Impact of urinary incontinence on female sexual health in women during midlife. Women’s Midlife Health 2015, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, M.; Kołodyńska, G.; Zalewska, A.; Andrzejewski, W. Comparative Assessment of Female Sexual Function Following Transobturator Midurethral Sling for Stress Urinary Incontinence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R., Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.G.; Coates, K.W.; Kammerer-Doak, D.; Khalsa, S.; Qualls, C. A short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2003, 14, 164–168; discussion 168, Erratum in Int. Urogynecol. J. 2004, 15, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptaszkowski, K.; Malkiewicz, B.; Zdrojowy, R.; Ptaszkowska, L.; Paprocka-Borowicz, M. Assessment of the Short-Term Effects after High-Inductive Electromagnetic Stimulation of Pelvic Floor Muscles: A Randomized, Sham-Controlled Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Mohandas, A.; Coyne, K.; Gelhorn, H.; Gauld, J.; Sikirica, V.; Milani, A.L. Assessment of the psychometric properties of the Short-Form Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) following surgical placement of Prolift+M: A transvaginal partially absorbable mesh system for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. J. Sex Med. 2012, 9, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strojek, K.; Strączyńska, A.; Radzimińska, A.; Weber-Rajek, M. The Effects of Extracorporeal Magnetic Innervation in the Treatment of Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Avery, K.; Donovan, J.; Peters, T.J.; Shaw, C.; Gotoh, M.; Abrams, P. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2004, 23, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uebersax, J.S.; Wyman, J.F.; Shumaker, S.A.; McClish, D.K.; Fantl, J.A. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Neurourol. Urodyn. 1995, 14, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelou, K.; Grigoriadis, T.; Diakosavvas, M.; Zacharakis, D.; Athanasiou, S. The Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: An Overview of the Recent Data. Cureus 2020, 12, e7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, H.K.; Kang, S.Y.; Chung, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.R. The Recent Review of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. J. Menopausal Med. 2015, 21, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Portman, D.J.; Gass, M.L. Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: New terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 2865–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.Y.; Tang, F.H.; Lin, K.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Loo, Z.X.; Long, C.Y. Effect of pelvic floor muscles exercises by extracorporeal magnetic innervations on the bladder neck and urinary symptoms. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2023, 86, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omodei, M.S.; Marques Gomes Delmanto, L.R.; Carvalho-Pessoa, E.; Schmitt, E.B.; Nahas, G.P.; Petri Nahas, E.A. Association Between Pelvic Floor Muscle Strength and Sexual Function in Postmenopausal Women. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilling, P.J.; Wilson, L.C.; Westenberg, A.M.; McAllister, W.J.; Kennett, K.M.; Frampton, C.M.; Bell, D.F.; Wrigley, P.M.; Fraundorfer, M.R. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of electromagnetic stimulation of the pelvic floor vs sham therapy in the treatment of women with stress urinary incontinence. BJU Int. 2009, 103, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgayar, S.L. Combined effects of high-intensity focused electromagnetic therapy and pelvic floor exercises on pelvic floor muscles and sexual function in postmenopausal women. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2024, 67, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González-Isaza, P.; Sánchez-Borrego, R.; Lugo Salcedo, F.; Rodríguez, N.; Vélez Rizo, D.; Fusco, I.; Callarelli, S. Pulsed Magnetic Stimulation for Stress Urinary Incontinence and Its Impact on Sexuality and Health. Medicina 2022, 58, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavinka, E.; Turcan, I.; Bader, K. The Use of FMS (Functional Magnetic Stimulation) for the Treatment of Female Pelvic Floor. J. Women’s Health Care 2019, 8, 497. Available online: https://www.longdom.org/open-access-pdfs/the-use-of-hifem-technology-in-the-treatment-of-pelvic-floor-muscles-as-a-cause-of-female-sexual-dysfunction-a-multicent.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Evans, K.L.; Berenholz, J.; Samuels, J.B.; Pezzella, A.; DeLucia, C.A. Prospective Multi-Center Study on Long-term Effectiveness of HIFEM procedure for Treatment for Urinary Incontinence and Female Sexual Dysfunction. J. Women’s Health Care 2023, 12, 625. Available online: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/prospective-multicenter-study-on-longterm-effectiveness-of-hifem-procedure-for-treatment-for-urinary-incontinence-and-female-sexua-97766.html (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhou, D.; Yu, W.; Jiao, W.; Shi, G. Efficacy of optimized pelvic floor training of YUN combined with pelvic floor magnetic stimulation on female moderate stress urinary incontinence and sexual function: A retrospective cohort study. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2022, 11, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Celenay, S.T.; Karaaslan, Y.; Ozdemir, E. Effects of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training on Sexual Dysfunction, Sexual Satisfaction of Partners, Urinary Symptoms, and Pelvic Floor Muscle Strength in Women with Overactive Bladder: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Sex. Med. 2022, 19, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, C.H.; Bø, K.; Catai, C.C.; Brito, L.G.O.; Driusso, P.; Tennfjord, M.K. Pelvic floor muscle training as treatment for female sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, 51–66.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzybowska, M.E.; Wydra, D. Responsiveness of two sexual function questionnaires: PISQ-IR and FSFI in women with pelvic floor disorders. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2021, 40, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudonienė, V.; Kirklytė, I.; Žlibinaitė, L.; Jerez-Roig, J.; Rutkauskaitė, R. Pelvic Floor Muscle Training versus Functional Magnetic Stimulation for Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pavarini, N.; Valadares, A.L.R.; Varella, G.M.; Brito, L.G.O.; Juliato, C.R.T.; Costa-Paiva, L. Sexual function after energy-based treatments of women with urinary incontinence. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athey, R.; Gray, T.; Kershaw, V.; Radley, S.; Jha, S. Coital Incontinence: A Multicentre Study Evaluating Prevalence and Associations. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2024, 35, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Qiu, K.; Guo, H.; Fan, M.; Yan, L. Conservative treatments for women with stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1517962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wiegel, M.; Meston, C.; Rosen, R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2005, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Year) | Randomization Process | Deviations from Intended Interventions | Missing Outcome Data | Measurement of the Outcome | Selection of the Reported Result | Overall RoB 2 Judgement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elgayar 2024 [17] | Some concerns—randomization described but allocation concealment and baseline balance for sexual activity/FSFI domains not fully reported. | Some concerns—participants and personnel were not clearly blinded; PFMT intensity and other co-interventions may have differed between groups. | Low risk—no major differential loss to follow-up for FSFI reported; analysis appears to include most randomized women. | Some concerns—FSFI is self-reported and outcome assessors were not blinded; knowledge of group assignment could have influenced responses. | Some concerns—protocol not publicly available; selective reporting of adverse events and incomplete detail on prespecified sexual outcomes. | Some concerns |

| González-Isaza 2022 [18] | Low risk—random allocation and sham control described; baseline characteristics broadly similar between groups. | Some concerns—sham protocol described but not all details on adherence and co-interventions; possibility of unblinding due to treatment sensations. | Low risk—follow-up at 14 weeks largely complete; no evidence of strongly differential attrition between arms. | Some concerns—FSFI is self-reported; blinding of outcome assessment not explicitly confirmed, and participants may have inferred allocation. | Some concerns—no registered protocol; FSFI and adverse events reported incompletely relative to continence outcomes. | Some concerns |

| Study (Year) | Confounding | Selection of Participants into the Study | Classification of Interventions | Deviations from Intended Interventions | Missing Data | Measurement of Outcomes | Selection of the Reported Result | Overall ROBINS-I Judgment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hlavinka 2019 [19] | Serious—single-arm cohort without control group; no adjustment for age, menopausal status, baseline sexual function, or concomitant therapies. | Moderate—convenience sample of treatment-seeking women; eligibility criteria only partially described. | Low—HIFEM regimen clearly defined and consistently applied. | Moderate—no blinding; co-interventions (PFMT, hormonal treatments) and adherence not systematically captured. | Moderate—follow-up to 3 months with limited reporting of attrition; unclear whether missing FSFI data were related to outcomes. | Moderate—FSFI is validated, but self-reported with unblinded participants and no independent outcome assessor. | Serious—no pre-registered protocol; sexual outcomes selectively emphasized, adverse events sparsely reported. | Serious |

| Evans 2023 [20] | Serious—prospective multicenter cohort without control group; substantial potential for confounding by indication, center-level practice, PFMT use, hormone therapy, and baseline sexual activity. | Moderate—participants were women undergoing HIFEM in routine practice; selection mechanisms only partly described. | Low—HIFEM treatment defined (6–8 sessions) with consistent classification of exposure. | Moderate—no blinding; concomitant conservative measures and lifestyle changes not controlled or fully reported. | Serious—9–12-month follow-up with incomplete and poorly described attrition; unclear handling of missing FSFI/PISQ-12 data. | Moderate—FSFI and PISQ-12 are validated, but self-reported; no blinding of participants or assessors. | Serious—lack of protocol; partial reporting of domain-level sexual outcomes and adverse events; potential for selective emphasis on favorable results. | Serious |

| Wang 2022 [21] | Serious—retrospective comparison of magnetic stimulation alone vs. magnetic + optimized PFMT; allocation strongly influenced by clinical judgment and patient preference; limited adjustment for confounders. | Moderate—inclusion based on treated moderate SUI cases; reasons for entering each treatment pathway are incompletely described. | Low—interventions (magnetic alone vs. magnetic + PFMT) clearly defined in records. | Moderate—adherence to PFMT and other conservative therapies not systematically captured; no blinding. | Serious—only a subset (n = 49 of 95) had analyzable PISQ-12 data; handling of missing sexual function data not clearly reported. | Moderate—PISQ-12 and ICIQ-UI SF are validated; outcomes self-reported with awareness of treatment; no blinded assessment. | Serious—no prespecified protocol; sexual outcomes reported for a subset of the cohort; limited adverse-event reporting. | Serious |

| Study (Year) | Country/Setting | Design and Population | UI Subtype | Device/Regimen | Comparator | Follow-Up | Sexual Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elgayar 2024 [17] | NR | RCT, postmenopausal women | NR (pelvic floor dysfunction; UI status NR) | HIFEM + PFMT; session details NR in abstract | PFMT alone | 8 weeks | FSFI |

| González-Isaza 2022 [18] | Colombia | Randomized, sham-controlled SUI | SUI | Pulsed magnetic stimulation; parameters per protocol | Simulation (sham) | 14 weeks | FSFI |

| Hlavinka 2019 [19] | Multicenter (US/EU) | Prospective multicenter cohort | Mixed UI/FSD | HIFEM protocol (chair); 6 sessions over 3 weeks (typical) | None (single arm) | 1–3 months | FSFI |

| Evans 2023 [20] | Multicenter | Prospective multicenter | UI + FSD | HIFEM; standardized 6–8 sessions | None (single arm) | 6 months | FSFI, PISQ-12 |

| Wang 2022 [21] | China | Retrospective cohort; n ≈ 95 | Moderate SUI | Pelvic floor magnetic stimulation ± optimized PFMT | Active comparator (magnetic alone) | 6–12 weeks | PISQ-12 |

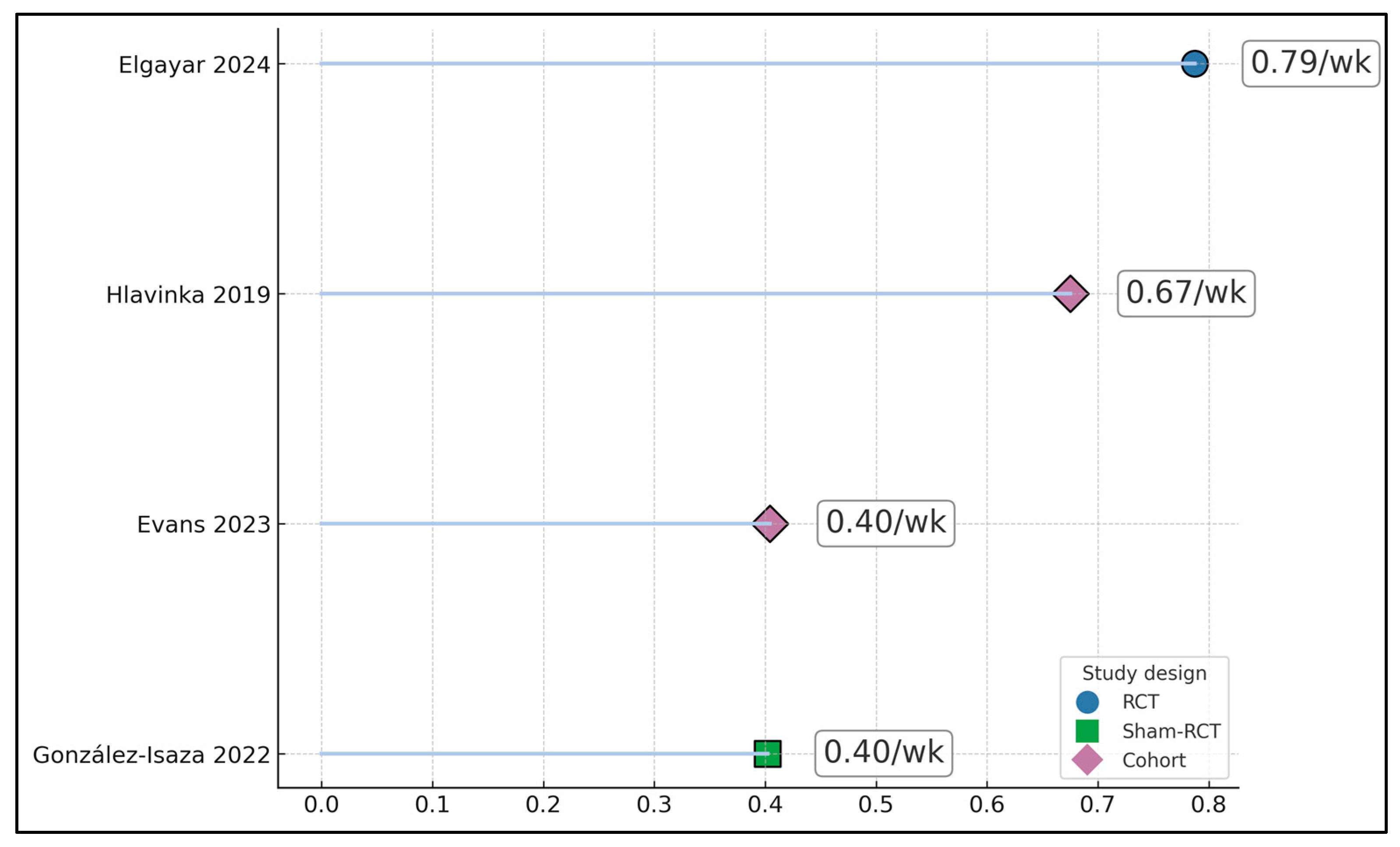

| Study | Instrument | Baseline Mean (SD)/Time | Change (Δ)/Between-Group Effect | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elgayar 2024 [17] | FSFI total | 16.04 | Follow-up 24.00 at 8 weeks; Δ + 7.96 within HIFEM+PFMT; between-group FSFI advantage +6.3 points vs. PFMT alone | <0.001 |

| González-Isaza 2022 [18] | FSFI total | 24.39 | Follow-up 23.19 at 14 weeks in active arm; Δ − 1.20; between-group FSFI difference +5.63 in favor of active vs. sham | <0.05 |

| Hlavinka 2019 [19] | FSFI total | 20.06 | Follow-up 30.69 post-treatment and 30.29 at 3 months; Δ + 10.23 at 3 months | <0.001 |

| Evans 2023 [20] | FSFI total; PISQ-12 | NR | Approximate mean increases +9.4 to +10.0 at ~6 months; exact baseline and follow-up means NR; PISQ-12 improved | NR |

| Wang 2022 [21] | PISQ-12 (direction per instrument used in paper) | 28.61 | Follow-up 32.47 at 12 weeks in magnetic + optimized PFMT arm; Δ + 3.86 | <0.05 |

| Study (Year) | N | Follow-Up Time Point Used | ICIQ-UI SF (Baseline → Follow-Up) | FSFI Total (Baseline → Follow-Up) | PISQ-12 (Baseline → Follow-Up) | 1 hr Pad Test (g) Baseline → Follow-Up | Oxford/EMG or PFM Strength | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elgayar 2024 [17] | 62 | End of treatment (8 sessions) | NR | 16.04 → 24.00 (Δ + 7.96) | NR | NR | PFM 2.7 ± 1.4 → 3.2 ± 1.2; combined regimen outperformed PFMT alone | NR |

| González-Isaza 2022 [18] | 47 | 14 weeks | 11.41 → 7.13 (Δ − 4.28) | 24.39 → 23.19 (Δ − 1.20) | NR | NR | Oxford 1.68 ± 0.99 → 2.81 ± 0.72 | NR |

| Hlavinka 2019 [19] | 30 | Post-treatment and 3-month | NR | 20.06 → 30.69 post; → 30.29 at 3-mo (Δ + 10.23) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Evans 2023 [20] | 31 | 9–12 months | Mean ICIQ-UI SF ↓ 71–72%; largest mean ↓ 8.6–9.3 points; small, nonsignificant relapse thereafter | Max FSFI gain +9.4 to +10.0 points | ↑ in desire, arousal, lubrication, satisfaction subdomains reported | NR | NR | NR |

| Wang 2022 [21] | 49 (of 95 total) | 12 weeks | 13.24 → 3.39 (Δ − 9.85; 74.4% reduction) | NR | 28.61 → 32.47 (Δ + 3.86); emotional 7.82 → 8.78; physiological 14.37 → 17.24; partner 6.43 → 6.45 (NS) | 6.4 → 1.6 g | EMG phasic 24.3 → 41.2 μV; tonic 19.2 → 38.9 μV | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sacarin, G.; Craina, M.; Sorop, B.; Bica, M.C.; Stelea, L.; Prodan, M.; Sorop, M.; Abu-Awwad, A.S.; Sorop-Florea, M.; Ruta, A.; et al. Chair-Based Magnetic Pelvic Floor Stimulation and Female Sexual Function in Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238496

Sacarin G, Craina M, Sorop B, Bica MC, Stelea L, Prodan M, Sorop M, Abu-Awwad AS, Sorop-Florea M, Ruta A, et al. Chair-Based Magnetic Pelvic Floor Stimulation and Female Sexual Function in Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238496

Chicago/Turabian StyleSacarin, Geanina, Marius Craina, Bogdan Sorop, Mihai Calin Bica, Lavinia Stelea, Mihaela Prodan, Madalina Sorop, Alina Simona Abu-Awwad, Maria Sorop-Florea, Adina Ruta, and et al. 2025. "Chair-Based Magnetic Pelvic Floor Stimulation and Female Sexual Function in Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238496

APA StyleSacarin, G., Craina, M., Sorop, B., Bica, M. C., Stelea, L., Prodan, M., Sorop, M., Abu-Awwad, A. S., Sorop-Florea, M., Ruta, A., & Nitu, R. (2025). Chair-Based Magnetic Pelvic Floor Stimulation and Female Sexual Function in Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8496. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238496