Rethinking Pulmonary Function Tests in Patients with Neuromuscular Disease: The Potential Role of Electrical Impedance Tomography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Electrical Impedance Tomography: Potential Benefits and Barriers to Its Use in Clinical Practice

- -

- As opposed to other imaging techniques such CT scans, EIT is a non-invasive, radiation-free, safe tool.

- -

- EIT does not depend upon the patient’s cooperation. Patients do not need to keep their lips sealed around a mouthpiece connected to a spirometer during testing, an enterprise that may be challenging for some NMD patients.

- -

- EIT can be utilized in both the upright and supine position: this is important in the context of patients who may present with very severe orthopnea.

- -

- While conventional PFTs can be fatiguing and non-repeatable due to the maximal effort required to perform the test properly, EIT can be repeated without discomfort or side effects.

- -

- As EIT devices are portable they can be used at a patient’s bedside, a feature that is especially important during an acute phase of a respiratory disease.

- -

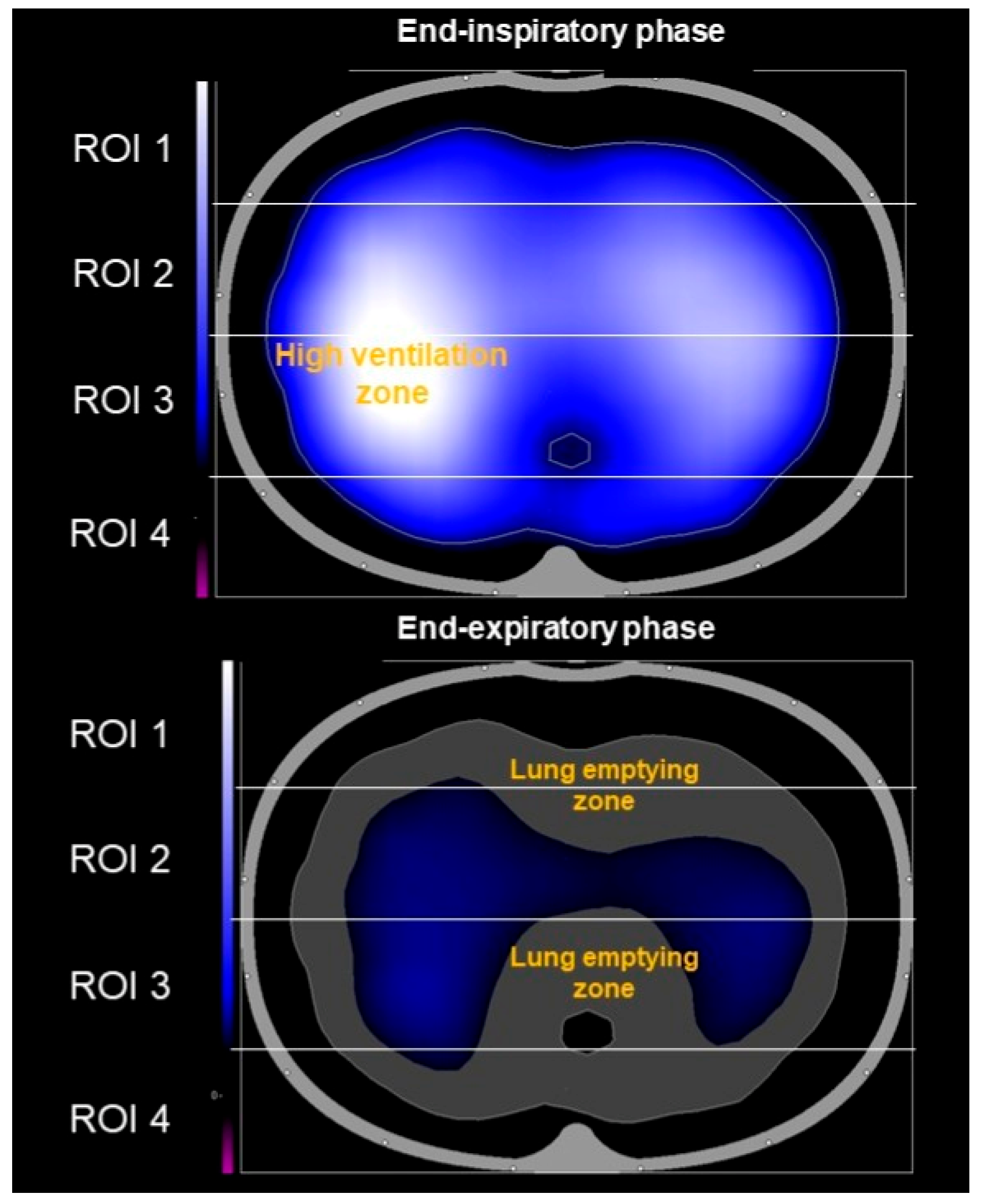

- Unlike static anatomical images from CT scans, EIT shows how each individual lung functions in real time by visualizing the distribution of regional lung ventilation and air content.

- -

- EIT facilitates early diagnosis of structural lung abnormalities and can detect atelectasis, pneumothorax, and pleural effusion (Figure 3).

- -

- Finally, EIT is able to detect even small structural changes over short time periods.

3. The Use of EIT in Neuromuscular Disease Patients: Current Experience and Limitations of Evidence

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perrin, C.; Unterborn, J.N.; Ambrosio, C.D.; Hill, N.S. Pulmonary complications of chronic neuromuscular diseases and their management. Muscle Nerve 2004, 29, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.; Mayer, O.H. Pulmonary function testing in patients with neuromuscular disease. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpa, B.; Pusalavidyasagar, S.; Iber, C. Respiratory issues and current management in neuromuscular diseases: A narrative review. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 6292–6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickenbach, J.; Czaplik, M.; Polier, M.; Marx, G.; Marx, N.; Dreher, M. Electrical impedance tomography for predicting failure of spontaneous breathing trials in patients with prolonged weaning. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, X.; Qu, H.; Wang, H. Technical principles and clinical applications of electrical impedance tomography in pulmonary monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzzo, G.; Pavlovsky, B.; Adler, A.; Baccinelli, W.; Bodor, D.L.; Damiani, L.F.; Franchineau, G.; Francovich, J.; Frerichs, I.; Giralt, J.A.S.; et al. Electrical impedance tomography monitoring in adult ICU patients: State-of-the-art, recommendations for standardized acquisition, processing, and clinical use, and future directions. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Möller, K.; Steinmann, D.; Frerichs, I.; Guttmann, J. Evaluation of an electrical impedance tomography-based Global Inhomogeneity Index for pulmonary ventilation distribution. Intensive Care Med. 2009, 35, 1900–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frerichs, I.; Zhao, Z.; Becher, T.; Zabel, P.; Weiler, N.; Vogt, B. Regional lung function determined by electrical impedance tomography during bronchodilator reversibility testing in patients with asthma. Physiol. Meas. 2016, 37, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambiaghi, B.; Moerer, O.; Kunze-Szikszay, N.; Mauri, T.; Just, A.; Dittmar, J.; Hahn, G. A spiky pattern in the course of electrical thoracic impedance as a very early sign of a developing pneumothorax. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2018, 38, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Minh, D.; Duong Trong, L.; McEwan, A. An efficient and fast multi-band focused bioimpedance solution with EIT-based reconstruction for pulmonary embolism assessment: A simulation study from massive to segmental blockage. Physiol. Meas. 2022, 43, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, K.; Mohammed, H.; Hopkins, P.; Corley, A.; Caruana, L.; Dunster, K.; Barnett, A.G.; Fraser, J.F. Single-lung transplant results in position dependent changes in regional ventilation: An observational case series using electrical impedance tomography. Can. Respir. J. 2016, 2016, 2471207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, L.G.; Santiago, R.; Florio, G.; Berra, L. Bedside evaluation of pulmonary embolism by electrical impedance tomography. Anesthesiology 2020, 132, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vianello, A.; Lionello, F.; Guarnieri, G. Electrical impedance tomography used during bronchoscopy in a patient with aspiration pneumonia. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023, 59, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, B.; Murphy, E.K.; Mallick, A.; Gutierrez, H.; Zhang, F.; Verga, S.; Smith, C.; Levy, S.D.; McIlduff, C.; Sarbesh, P.; et al. A robust and novel electrical impedance metric of pulmonary function in ALS patients. Physiol. Meas. 2020, 41, 044005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkove, S.B.; McIlduff, C.E.; Stommel, E.; Levy, S.; Smith, C.; Gutierrez, H.; Verga, S.; Samaan, S.; Yator, C.; Nanda, A.; et al. Assessing pulmonary function in ALS using electrical impedance tomography. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2024, 25, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, G.; Shaw, A.; Bolt, K.; Verity, R.; Nataraj, R.T.; Schellenberg, K.L. Thoracic electric impedance tomography detects lung volume changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2025, 71, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkove, S.B.; McIlduff, C.E.; Stommel, E.; Levy, S.; Smith, C.; Gutierrez, H.; Verga, S.; Samaan, S.; Yator, C.; Nanda, A.; et al. Thoracic electrical impedance tomography for assessing progression of pulmonary dysfunction in ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2025, 26, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigatto, A.V.; Kao, T.-J.; Mueller, J.L.; Baker, C.D.; DeBoer, E.M.; Kupfer, O. Electrical impedance tomography detects changes in ventilation after airway clearance in spinal muscular atrophy type I. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2021, 294, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaulta, C.; Messerli, F.; Rodriguez, R.; Klein, A.; Riedel, T. Changes in ventilation distribution in children with neuromuscular disease using the insufflator/exsufflator technique: An observational study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, E.; Rovida, S.; Cammarota, G.; Biamonte, E.; Troisi, L.; Cosenza, L.; Pelaia, C.; Navalesi, P.; Longhini, F.; Bruni, A. Benefits of secretion clearance with high frequency percussive ventilation in tracheostomized critically ill patients: A pilot study. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2023, 37, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraino, T. An introduction to the clinical application and interpretation of electrical impedance tomography. Respir. Care 2022, 67, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomicic, V.; Cornejo, R. Lung monitoring with electrical impedance tomography: Technical considerations and clinical applications. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 3122–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, D.; Putowski, Z.; Czok, M.; Krzych, L.J. Electrical impedance tomography as a tool for monitoring mechanical ventilation. An introduction to the technique. Adv. Med. Sci. 2022, 66, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type of Study | Population | EIT Analysis | EIT Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Munir B et al. [14] | Physiological pilot study | 7 ALS pts 10 healthy volunteers | Correlation with standard PFT | 32 channels |

| Rutkove SB et al. [15] | Physiological study | 32 ALS pts 32 healthy controls | Correlation with standard PFT | 32 channels |

| Hansen G et al. [16] | Prospective cohort study | 21 ALS pts | Impact of supine posture on lung volumes | 16 channels |

| Rutkove SB et al. [17] | Prospective cohort study | 32 ALS pts 32 healthy controls | 4 mo decline of pulmonary function | 32 channels |

| Pigatto AV et al. [18] | Physiological pilot study | 6 type 1 SMA pts | Effect of MI-E on lung volumes | 16 channels |

| Casaulta C et al. [19] | Physiological pilot study | 8 non-ambulatory NMD pts | Effect of MI-E on ventilation distribution | NA |

| Garofalo E et al. [20] | Physiological pilot study | 15 tracheostomized pts | Benefit of HFPV on secretion clearance | 16 channels |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vianello, A.; Guarnieri, G.; Lionello, F. Rethinking Pulmonary Function Tests in Patients with Neuromuscular Disease: The Potential Role of Electrical Impedance Tomography. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238486

Vianello A, Guarnieri G, Lionello F. Rethinking Pulmonary Function Tests in Patients with Neuromuscular Disease: The Potential Role of Electrical Impedance Tomography. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238486

Chicago/Turabian StyleVianello, Andrea, Gabriella Guarnieri, and Federico Lionello. 2025. "Rethinking Pulmonary Function Tests in Patients with Neuromuscular Disease: The Potential Role of Electrical Impedance Tomography" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238486

APA StyleVianello, A., Guarnieri, G., & Lionello, F. (2025). Rethinking Pulmonary Function Tests in Patients with Neuromuscular Disease: The Potential Role of Electrical Impedance Tomography. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238486