TP53 Mutations in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: From Backup to Game Changer

Abstract

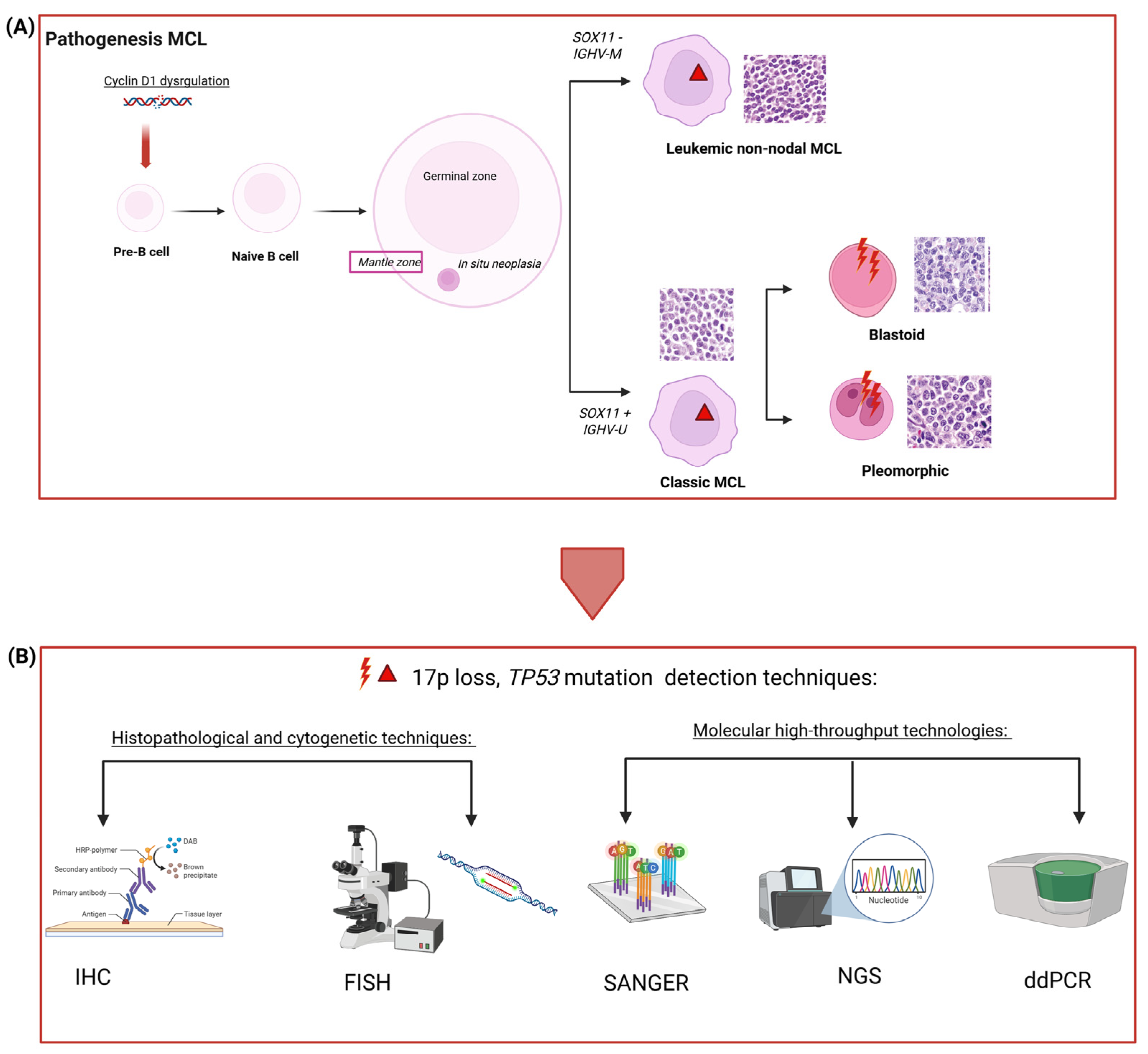

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Evidence of TP53’s Role in Resistance to Treatments and Poor Prognosis

| Clinical Trials | TP53 Mutations and\or Deletion Assessment | Treatment Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| European MCL Younger trial [30] | RQ-PCR | High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation |

| Nordic MCL2 and MCL3 [10] | IHC, NGS | cytarabine, rituximab, and autologous stem-cell transplant (ASCT) |

| Korean, Multicenter, Retrospective Analysis [31] | IHC | Bendamustine and rituximab (BR) |

| TRIANGLE [32] | IHC | Ibrutinib in addition to chemoimmunotherapy |

| SHINE and ECHO [33,34] | IHC | Ibrutinib or acalabrutinib in addition to chemotherapy |

| BoVen [36] | IHC, NGS | Zanabrutinib, obinutuzumab, and venetoclax |

| SYMPATICO [37] | NGS | Ibrutinib combined with venetoclax |

| VR-BAC [38] | FISH, Sanger, NGS | Venetoclax in high-risk subgroups |

| ZUMA2 [39] | NGS, ddPCR | Brexucabtagene autoleucel |

| TARMAC [40] | FISH, NGS | CAR-T in combination with ibrutinib |

| NP30179 and NCT03075696 [42,43] | IHC | Glofitamab |

3. Immunohistochemistry and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization to Detect TP53 Point Mutation and Aberrations: Strengths and Limitations

4. Comparison Between Sanger and Next Generation Sequencing: Strengths and Limitations

5. Could Droplet-Digital PCR Be a Valuable Tool in Detecting TP53 Hotspots in the Hematological Field?

6. Finding the Right Method: Key Considerations

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Navarro, A.; Beà, S.; Jares, P.; Campo, E. Molecular Pathogenesis of Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 34, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Eyre, T.A.; Lewis, K.L.; Thompson, M.C.; Cheah, C.Y. New Directions for Mantle Cell Lymphoma in 2022. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2022, 42, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.V.; Nyvold, C.G.; Hansen, M.H. Mantle cell lymphoma and the evidence of an immature lymphoid component. Leuk. Res. 2022, 115, 106824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomben, R.; Ferrero, S.; D’Agaro, T.; Dal Bo, M.; Re, A.; Evangelista, A.; Carella, A.M.; Zamò, A.; Vitolo, U.; Omedè, P.; et al. A B-cell receptor-related gene signature predicts survival in mantle cell lymphoma: Results from the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi MCL-0208 trial. Haematologica 2018, 103, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obr, A.; Procházka, V.; Jirkuvová, A.; Urbánková, H.; Kriegova, E.; Schneiderová, P.; Vatolíková, M.; Papajík, T. TP53 Mutation and Complex Karyotype Portends a Dismal Prognosis in Patients with Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018, 18, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotta-Huspenina, J.; Koch, I.; de Leval, L.; Keller, G.; Klier, M.; Bink, K.; Kremer, M.; Raffeld, M.; Fend, F.; Quintanilla-Martinez, L. The impact of cyclin D1 mRNA isoforms, morphology and p53 in mantle cell lymphoma: p53 alterations and blastoid morphology are strong predictors of a high proliferation index. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izban, K.F.; Alkan, S.; Singleton, T.P.; Hsi, E.D. Multiparameter Immunohistochemical Analysis of the Cell Cycle Proteins Cyclin D1, Ki-67, p21WAF1, p27KIP1, and p53 in Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2000, 124, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.M.; Hassan, M.; Freiburghaus, C.; Eskelund, C.W.; Geisler, C.; Räty, R.; Kolstad, A.; Sundström, C.; Glimelius, I.; Grønbæk, K.; et al. p53 is associated with high-risk and pinpoints TP53 missense mutations in mantle cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 191, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakhdari, A.; Ok, C.Y.; Patel, K.P.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Yin, C.C.; Zuo, Z.; Hu, S.; Routbort, M.J.; Luthra, R.; Medeiros, L.J.; et al. TP53 mutations are common in mantle cell lymphoma, including the indolent leukemic non-nodal variant. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2019, 41, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskelund, C.W.; Dahl, C.; Hansen, J.W.; Westman, M.; Kolstad, A.; Pedersen, L.B.; Montano-Almendras, C.P.; Husby, S.; Freiburghaus, C.; Ek, S.; et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood 2017, 130, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareckova, A.; Malcikova, J.; Tom, N.; Pal, K.; Radova, L.; Salek, D.; Janikova, A.; Moulis, M.; Smardova, J.; Kren, L.; et al. ATM and TP53 mutations show mutual exclusivity but distinct clinical impact in mantle cell lymphoma patients. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeu, F.; Martin-Garcia, D.; Clot, G.; Díaz-Navarro, A.; Duran-Ferrer, M.; Navarro, A.; Vilarrasa-Blasi, R.; Kulis, M.; Royo, R.; Gutiérrez-Abril, J.; et al. Genomic and epigenomic insights into the origin, pathogenesis, and clinical behavior of mantle cell lymphoma subtypes. Blood 2020, 136, 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pararajalingam, P.; Coyle, K.M.; Arthur, S.E.; Thomas, N.; Alcaide, M.; Meissner, B.; Boyle, M.; Qureshi, Q.; Grande, B.M.; Rushton, C.; et al. Coding and noncoding drivers of mantle cell lymphoma identified through exome and genome sequencing. Blood 2020, 136, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, E.E.; Hatipoğlu, T.; Kurşun, D.; Hu, X.; Akman, B.; Yuan, H.; Danyeli, A.E.; Alacacıoğlu, İ.; Özkal, S.; Olgun, A.; et al. Whole Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Cancer-Related, Prognostically Significant Transcripts and Tumor-Infiltrating Immunocytes in Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Cells 2022, 11, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Silkenstedt, E.; Dreyling, M.; Beà, S. Biological and clinical determinants shaping heterogeneity in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 3652–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenhuber, E.R.; Lowe, S.W. Putting p53 in Context. Cell 2017, 170, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Bai, O. Function and regulation of lipid signaling in lymphomagenesis: A novel target in cancer research and therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 154, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obr, A.; Klener, P.; Furst, T.; Kriegova, E.; Zemanova, Z.; Urbankova, H.; Jirkuvova, A.; Petrackova, A.; Malarikova, D.; Forsterova, K.; et al. A high TP53 mutation burden is a strong predictor of primary refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 191, e103–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, K.A.; Piecuch, A.; Sady, M.; Gajewski, Z.; Flis, S. Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer—Current Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P.; Wang, M. High-risk MCL: Recognition and treatment. Blood 2025, 145, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiyama, Y.; Fujita, S.; Shima, Y.; Yamagata, K.; Katsumoto, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Honma, D.; Adachi, N.; Araki, K.; Kato, A.; et al. CDKN1C-mediated growth inhibition by an EZH1/2 dual inhibitor overcomes resistance of mantle cell lymphoma to ibrutinib. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 2314–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudelius, M.; Pittaluga, S.; Nishizuka, S.; Pham, T.H.-T.; Fend, F.; Jaffe, E.S.; Quintanilla-Martinez, L.; Raffeld, M. Constitutive activation of Akt contributes to the pathogenesis and survival of mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2006, 108, 1668–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambino, S.; Quaglia, F.M.; Galasso, M.; Cavallini, C.; Chignola, R.; Lovato, O.; Giacobazzi, L.; Caligola, S.; Adamo, A.; Putta, S.; et al. B-cell receptor signaling activity identifies patients with mantle cell lymphoma at higher risk of progression. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahal, R.; Frick, M.; Romero, R.; Korn, J.M.; Kridel, R.; Chan, F.C.; Meissner, B.; Bhang, H.-E.; Ruddy, D.; Kauffmann, A.; et al. Pharmacological and genomic profiling identifies NF-κB–targeted treatment strategies for mantle cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Ali, R.; Bouska, A.; Jochum, D.; Kesireddy, M.; Mahov, S.; Lownik, J.; Zhang, W.; Lone, W.; Soma, M.A.; et al. Functional genomics and tumor microenvironment analysis reveal prognostic biological subtypes in Mantle cell lymphoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decombis, S.; Bellanger, C.; Le Bris, Y.; Madiot, C.; Jardine, J.; Santos, J.C.; Boulet, D.; Dousset, C.; Menard, A.; Kervoelen, C.; et al. CARD11 gain of function upregulates BCL2A1 expression and promotes resistance to targeted therapies combination in B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2023, 142, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granau, A.M.; Andersen, P.A.; Jakobsen, T.; Taouxi, K.; Dalila, N.; Mogensen, J.B.; Kristensen, L.S.; Grønbæk, K.; Dimopoulos, K. Concurrent Inhibition of Akt and ERK Using TIC-10 Can Overcome Venetoclax Resistance in Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Dreyling, M.; Seymour, J.F.; Wang, M. High-Risk Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Definition, Current Challenges, and Management. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 4302–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefancikova, L.; Moulis, M.; Fabian, P.; Ravcukova, B.; Vasova, I.; Muzik, J.; Malcikova, J.; Falkova, I.; Slovackova, J.; Smardova, J. Loss of the p53 tumor suppressor activity is associated with negative prognosis of mantle cell lymphoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2010, 36, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfau-Larue, M.H.; Klapper, W.; Berger, F.; Jardin, F.; Briere, J.; Salles, G.; Casasnovas, O.; Feugier, P.; Haioun, C.; Ribrag, V.; et al. High-dose cytarabine does not overcome the adverse prognostic value of CDKN2A and TP53 deletions in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2015, 126, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.O.; Lee, G.W.; Kwak, J.Y.; Eom, H.S.; Jo, J.C.; Choi, Y.S.; Oh, S.Y.; Kim, W.S. Bendamustine Plus Rituximab for Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Korean, Multicenter Retrospective Analysis. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 6083–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyling, M.; Doorduijn, J.; Giné, E.; Jerkeman, M.; Walewski, J.; Hutchings, M.; Mey, U.; Riise, J.; Trneny, M.; Vergote, V.; et al. Ibrutinib combined with immunochemotherapy with or without autologous stem-cell transplantation versus immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with mantle cell lymphoma (TRIANGLE): A three-arm, randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet 2024, 403, 2293–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Jurczak, W.; Jerkeman, M.; Trotman, J.; Zinzani, P.L.; Belada, D.; Boccomini, C.; Flinn, I.W.; Giri, P.; Goy, A.; et al. Ibrutinib plus Bendamustine and Rituximab in Untreated Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2482–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Salek, D.; Belada, D.; Song, Y.; Jurczak, W.; Kahl, B.S.; Paludo, J.; Chu, M.P.; Kryachok, I.; Fogliatto, L.; et al. Acalabrutinib Plus Bendamustine-Rituximab in Untreated Mantle Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 2276–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Lee, H.; Chuang, H.; Wagner-Bartak, N.; Hagemeister, F.; Westin, J.; Fayad, L.; Samaniego, F.; Turturro, F.; Oki, Y.; et al. Ibrutinib in combination with rituximab in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: A single-centre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Soumerai, J.; Abramson, J.S.; Barnes, J.A.; Caron, P.; Chhabra, S.; Chabowska, M.; Dogan, A.; Falchi, L.; Grieve, C.; et al. Zanubrutinib, obinutuzumab, and venetoclax for first-line treatment of mantle cell lymphoma with a TP53 mutation. Blood 2025, 145, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Jurczak, W.; Trneny, M.; Belada, D.; Wrobel, T.; Ghosh, N.; Keating, M.M.; van Meerten, T.; Alvarez, R.F.; von Keudell, G.; et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (SYMPATICO): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visco, C.; Tabanelli, V.; Sacchi, M.V.; Evangelista, A.; Quaglia, F.M.; Fiori, S.; Bomben, R.; Tisi, M.C.; Riva, M.; Merli, A.; et al. Rituximab, bendamustine, and cytarabine followed by venetoclax in older patients with high-risk mantle cell lymphoma (FIL_V-RBAC): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2025, 12, e777–e788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Munoz, J.; Goy, A.; Locke, F.L.; Jacobson, C.A.; Hill, B.T.; Timmerman, J.M.; Holmes, H.; Jaglowski, S.; Flinn, I.W.; et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minson, A.; Hamad, N.; Cheah, C.Y.; Tam, C.S.; Blombery, P.; Westerman, D.; Ritchie, D.S.; Morgan, H.; Holzwart, N.; Lade, S.; et al. CAR T cells and time-limited ibrutinib as treatment for relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: The phase 2 TARMAC study. Blood 2024, 143, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Munoz, J.; Goy, A.; Locke, F.L.; Jacobson, C.A.; Hill, B.T.; Timmerman, J.M.; Holmes, H.; Jaglowski, S.; Flinn, I.W.; et al. Three-Year Follow-Up of KTE-X19 in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma, Including High-Risk Subgroups, in the ZUMA-2 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, T.J.; Carlo-Stella, C.; Morschhauser, F.; Bachy, E.; Crump, M.; Trněný, M.; Bartlett, N.L.; Zaucha, J.; Wrobel, T.; Offner, F.; et al. Glofitamab in Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Results from a Phase I/II Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 318–328. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, T.J.; Trněný, M.; Carlo-Stella, C.; Zaucha, J.M.; Wrobel, T.; Offner, F.; Dickinson, M.J.; Tani, M.; Crump, M.; Bartlett, N.L.; et al. Paper: Glofitamab Induces High Response Rates and Durable Remissions in Patients (Pts) with Heavily Pretreated Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Including Those with a Poor Prognosis: Subgroup Results from a Phase I/II Study. Blood 2024, 144, 1631. [Google Scholar]

- Croci, G.A.; Hoster, E.; Beà, S.; Clot, G.; Enjuanes, A.; Scott, D.W.; Cabeçadas, J.; Veloza, L.; Campo, E.; Clasen-Linde, E.; et al. Reproducibility of histologic prognostic parameters for mantle cell lymphoma: Cytology, Ki67, p53 and SOX11. Virchows Arch. 2020, 477, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.C.C.; Nerurkar, S.N.; Cai, H.Y.; Ng, H.H.M.; Wu, D.; Wee, Y.T.F.; Lim, J.C.T.; Yeong, J.; Lim, T.K.H. Overview of multiplex immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence techniques in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun. 2020, 40, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yemelyanova, A.; Vang, R.; Kshirsagar, M.; Lu, D.; A Marks, M.; Shih, I.M.; Kurman, R.J. Immunohistochemical staining patterns of p53 can serve as a surrogate marker for TP53 mutations in ovarian carcinoma: An immunohistochemical and nucleotide sequencing analysis. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.J.; Dwight, T.; Gill, A.J.; Dickson, K.-A.; Zhu, Y.; Clarkson, A.; Gard, G.B.; Maidens, J.; Valmadre, S.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; et al. Assessing mutant p53 in primary high-grade serous ovarian cancer using immunohistochemistry and massively parallel sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheubeck, G.; Jiang, L.; Hermine, O.; Kluin-Nelemans, H.C.; Schmidt, C.; Unterhalt, M.; Rosenwald, A.; Klapper, W.; Evangelista, A.; Ladetto, M.; et al. Clinical outcome of Mantle Cell Lymphoma patients with high-risk disease (high-risk MIPI-c or high p53 expression). Leukemia 2023, 37, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HALO Quantitative Image Analysis for Pathology. Available online: https://www.leicabiosystems.com/it-it/digital-pathology/analyze/halo/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Gao, L.-M.; Xiang, X.-Y.; Zhang, W.-Y.; Liu, W.-P. Prognostic value and computer image analysis of p53 in mantle cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2022, 101, 2271–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.; Von Voithenberg, L.V.; Kaigala, G.V. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH): History, limitations and what to expect from micro-scale FISH? Micro Nano Eng. 2018, 1, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, S.; Ragaini, S. Advancing Mantle Cell Lymphoma Risk Assessment: Navigating a Moving Target. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 43, e70072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, A.; Alexandrov, L.B. Significance and limitations of the use of next-generation sequencing technologies for detecting mutational signatures. DNA Repair 2021, 107, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advantages and Limitations of Sanger Sequencing. Genetic Education. Available online: https://geneticeducation.co.in/advantages-and-limitations-of-sanger-sequencing/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Khouja, M.; Jiang, L.; Pal, K.; Stewart, P.J.; Regmi, B.; Schwarz, M.; Klapper, W.; Alig, S.K.; Darzentas, N.; Kluin-Nelemans, H.C.; et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis by targeted sequencing identifies risk factors and predicts patient outcome in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Results from the EU-MCL network trials. Leukemia 2024, 38, 2675–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Zeng, R.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, C.; Xia, C.; Ou, Q.; Bao, H.; et al. Genomic signatures in plasma circulating tumor DNA reveal treatment response and prognostic insights in mantel cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Jain, P.; Yao, Y.; Wang, M. Advances in the assessment of minimal residual disease in mantle cell lymphoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarikova, D.; Berkova, A.; Obr, A.; Blahovcova, P.; Svaton, M.; Forsterova, K.; Kriegova, E.; Prihodova, E.; Pavlistova, L.; Petrackova, A.; et al. Concurrent TP53 and CDKN2A Gene Aberrations in Newly Diagnosed Mantle Cell Lymphoma Correlate with Chemoresistance and Call for Innovative Upfront Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroClonality—NDC Assay by Univ8 Genomics. Available online: https://univ8genomics.com/euroclonality-ndc/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Genuardi, E.; Romano, G.; Beccuti, M.; Alessandria, B.; Mannina, D.; Califano, C.; Scalabrini, D.R.; Cortelazzo, S.; Ladetto, M.; Ferrero, S.; et al. Application of the Euro Clonality next-generation sequencing-based marker screening approach to detect immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangements in mantle cell lymphoma patients: First data from the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi MCL0208 trial. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 194, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschewski, M.; Rossi, D.; Kurtz, D.M.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Wilson, W.H. Circulating Tumor DNA in Lymphoma Principles and Future Directions. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022, 3, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moia, R.; Carazzolo, M.E.; Cosentino, C.; Almasri, M.; Talotta, D.; Tabanelli, V.; Motta, G.; Melle, F.; Sacchi, M.V.; Evangelista, A.; et al. TP53, CD36 Mutations and CDKN2A Loss Predict Poor Outcome in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Molecular Analysis of the FIL V-Rbac Phase 2 Trial. Blood 2024, 144 (Suppl. S1), 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, L.M.; de Groen, R.A.L.; de Groot, F.A.; Noordenbos, T.; van Wezel, T.; van Eijk, R.; Ruano, D.; Diepstra, A.; Koens, L.; Nicolae-Cristea, A.; et al. Real-world routine diagnostic molecular analysis for TP53 mutational status is recommended over p53 immunohistochemistry in B-cell lymphomas. Virchows Arch. 2024, 485, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, S.; Balducci, S.; Guerrini, F.; Del Re, M.; Cacciola, R. Digital Droplet PCR in Hematologic Malignancies: A New Useful Molecular Tool. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccaro, N.; Tota, G.; Anelli, L.; Zagaria, A.; Specchia, G.; Albano, F. Digital PCR: A Reliable Tool for Analyzing and Monitoring Hematologic Malignancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Mu, W.; Gu, J.; Xiao, M.; Huang, L.; Zheng, M.; Li, C.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Long, X. TP53-Mutated Circulating Tumor DNA for Disease Monitoring in Lymphoma Patients after CAR T Cell Therapy. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obr, A.; Klener Jr, P.; Kriegova, E.; Zemanova, Z.; Urbankova, H.; Jirkuvova, A.; Petrackova, A.; Cudova, B.; Sedlarikova, L.; Prochazka, V.K.; et al. High TP53 Mutation Load Predicts Primary Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2019, 134, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Techniques | Accuracy | Sensitivity (VAF) | Quantification | Costs | TP53 Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Low | - | Qualitative evaluation manual or automatic (QuPath/HALO) | Low | Protein localization (overexpression, missense variant, truncating variant, wild type) |

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) | Intermediate | ≥5–10% | Manual with fluorescence microscope or automated with imaging software | Intermediate High | Deletion 17p |

| Sanger sequencing | Intermediate/High | 15–20% | Not quantitative | High | Mutation validation, and research of known targets |

| Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and targeted NGS (tNGS) | High | 2–5% and 0.1–1% (the sensitivity depends on the coverage adopted) | Quantitative | High Intermediate | Somatic nucleotide variations (SNVs), germline mutations, clonal evolution, and copy number variations (CNVs) |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Very high | 0.01–0.1% | Absolute quantification | Intermediate | Somatic nucleotide variations (SNVs), copy number variations (CNVs), and monitoring MRD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carazzolo, M.E.; Moioli, A.; Visco, C. TP53 Mutations in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: From Backup to Game Changer. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238480

Carazzolo ME, Moioli A, Visco C. TP53 Mutations in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: From Backup to Game Changer. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238480

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarazzolo, Maria Elena, Alessia Moioli, and Carlo Visco. 2025. "TP53 Mutations in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: From Backup to Game Changer" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238480

APA StyleCarazzolo, M. E., Moioli, A., & Visco, C. (2025). TP53 Mutations in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: From Backup to Game Changer. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238480