Severe Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in a Patient with Cardiac Sarcoidosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

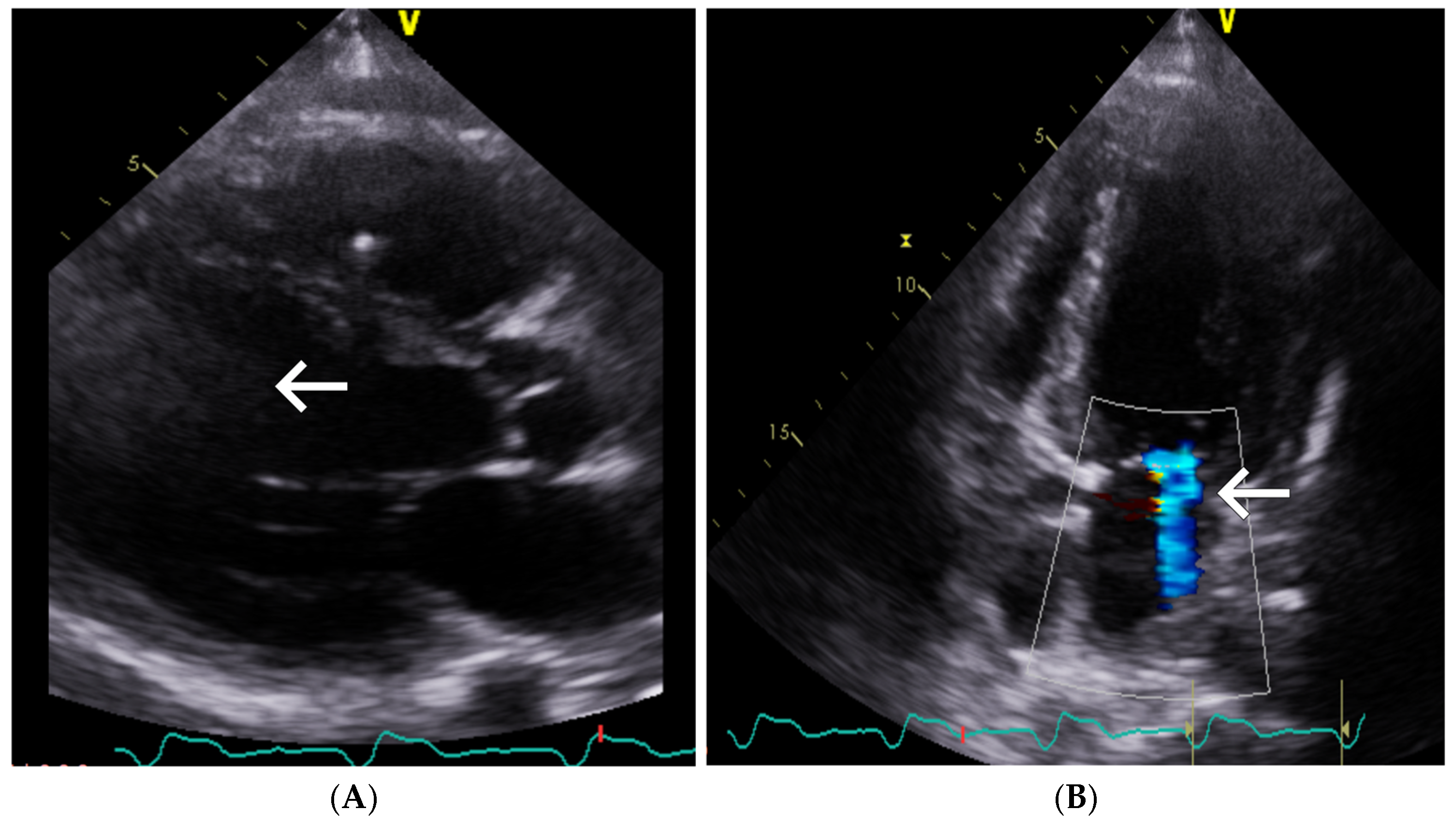

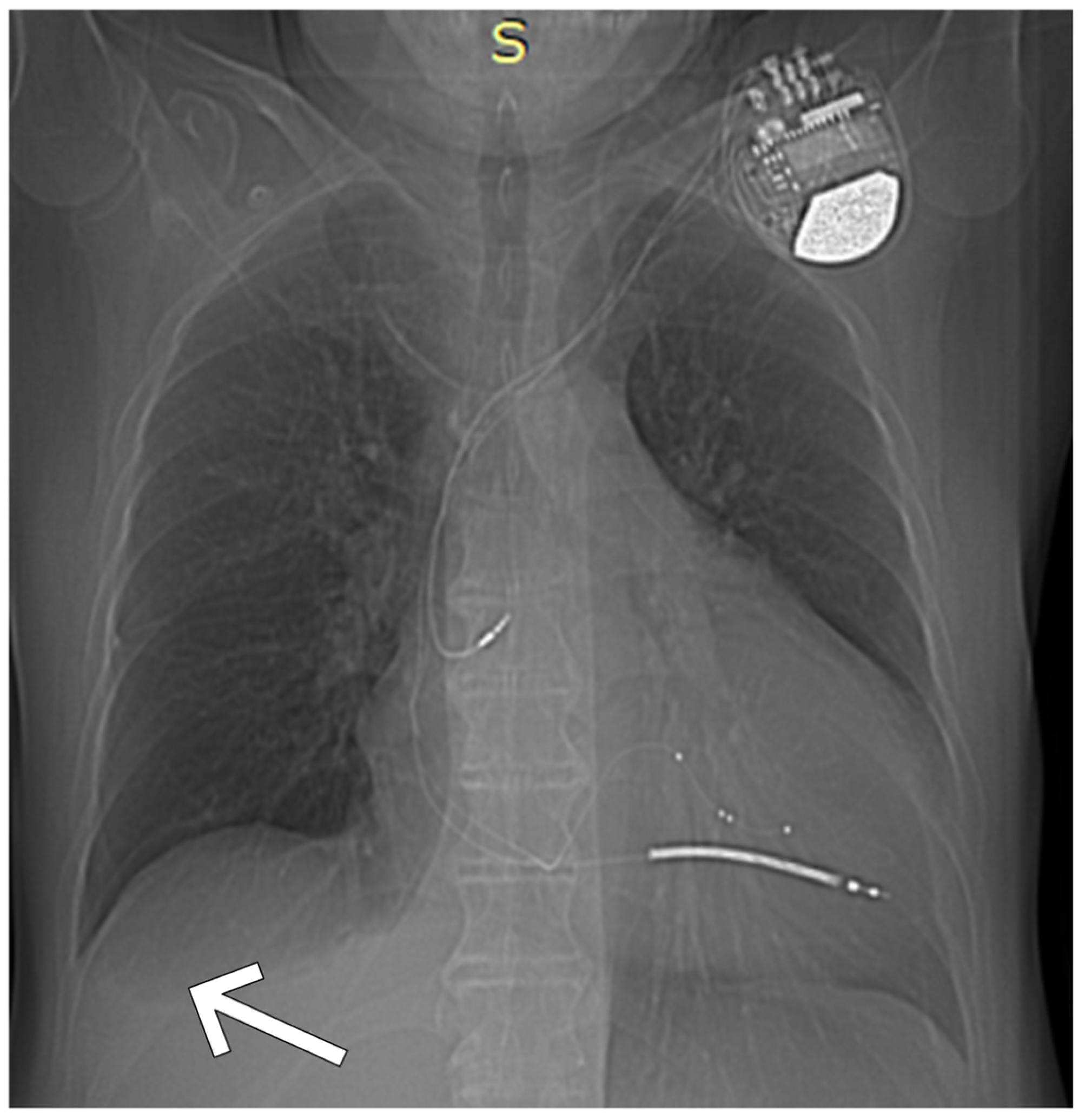

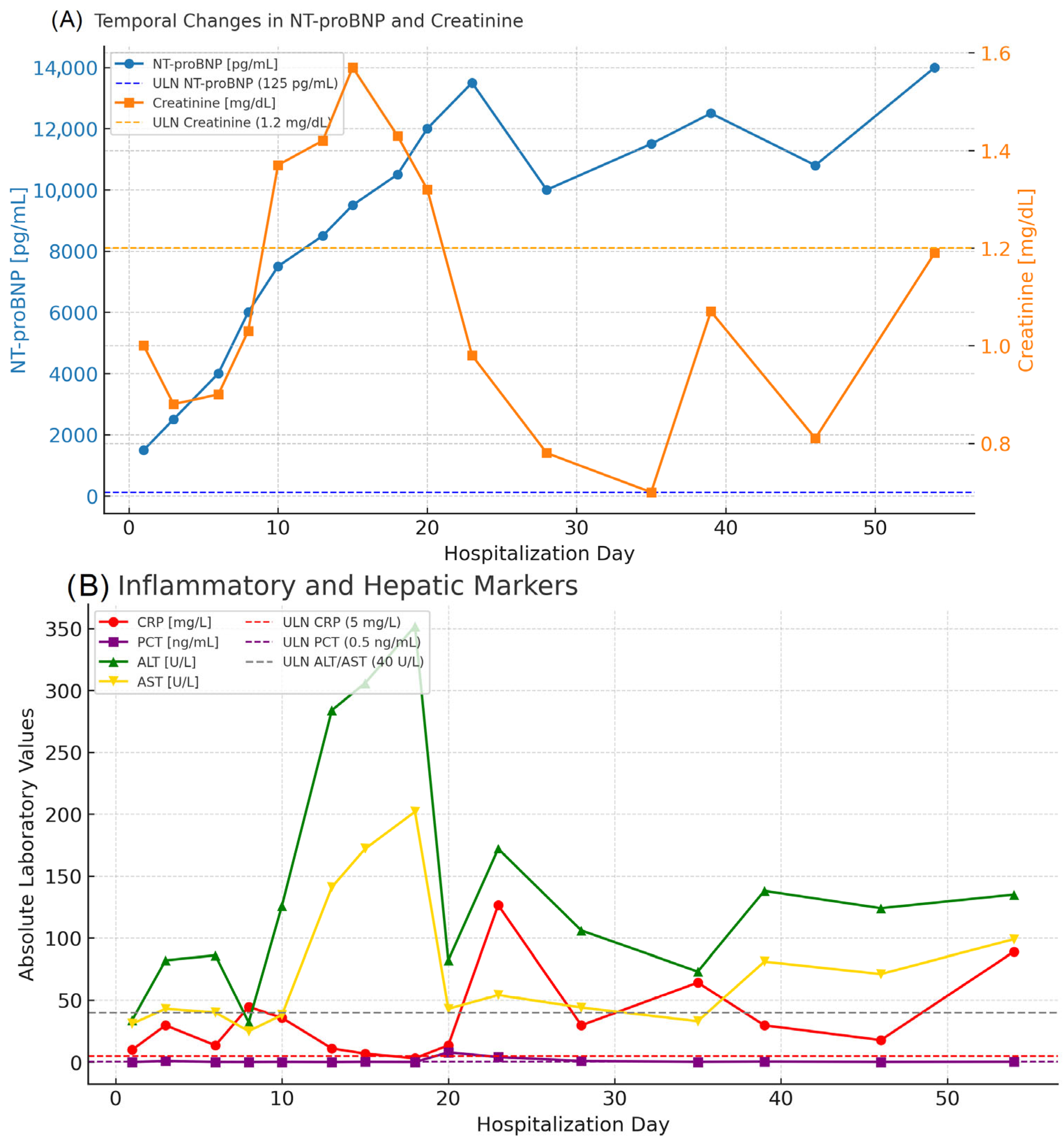

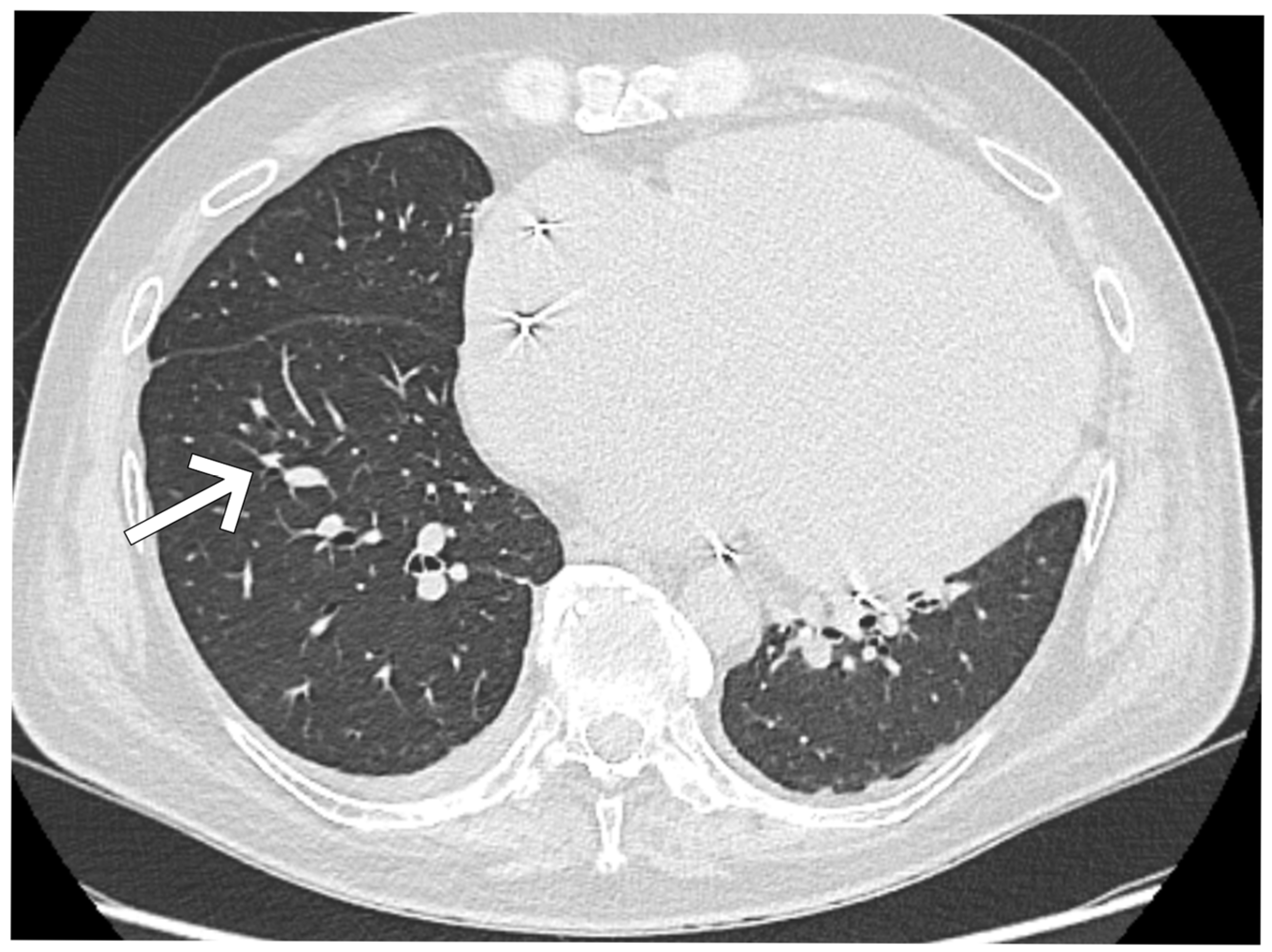

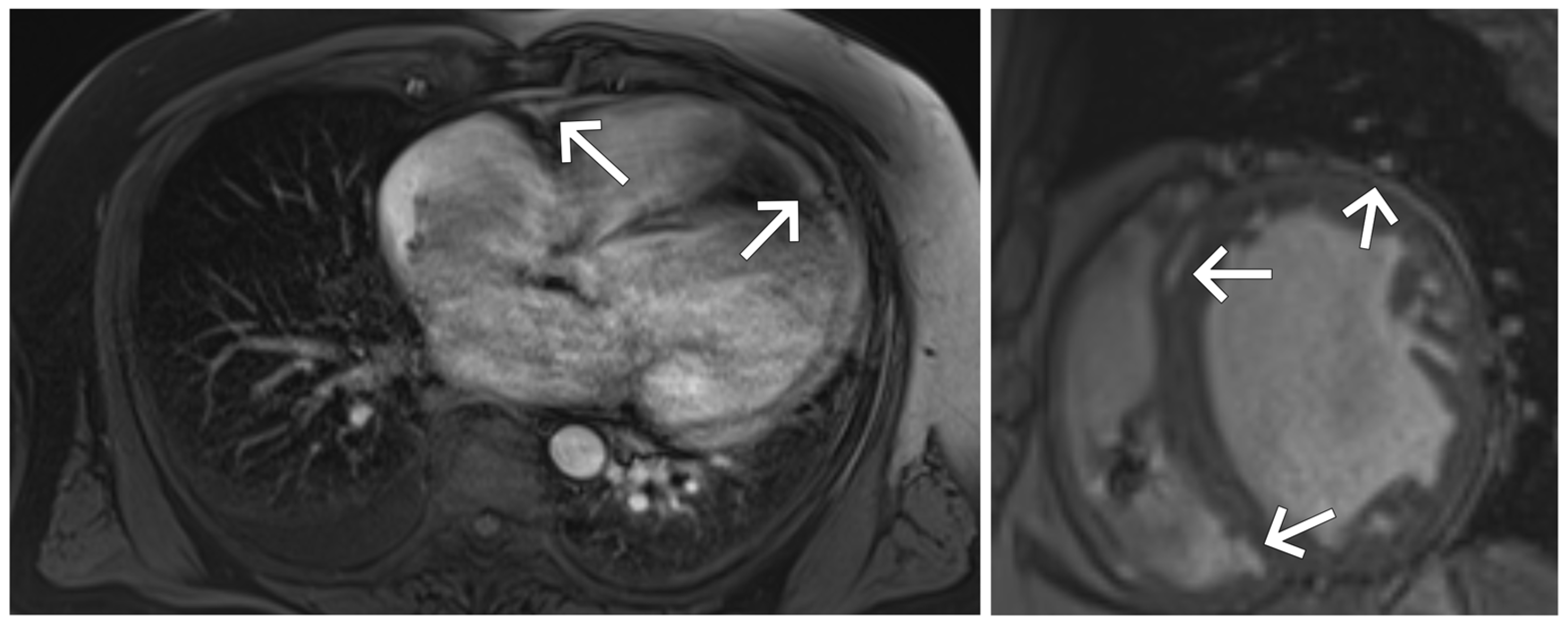

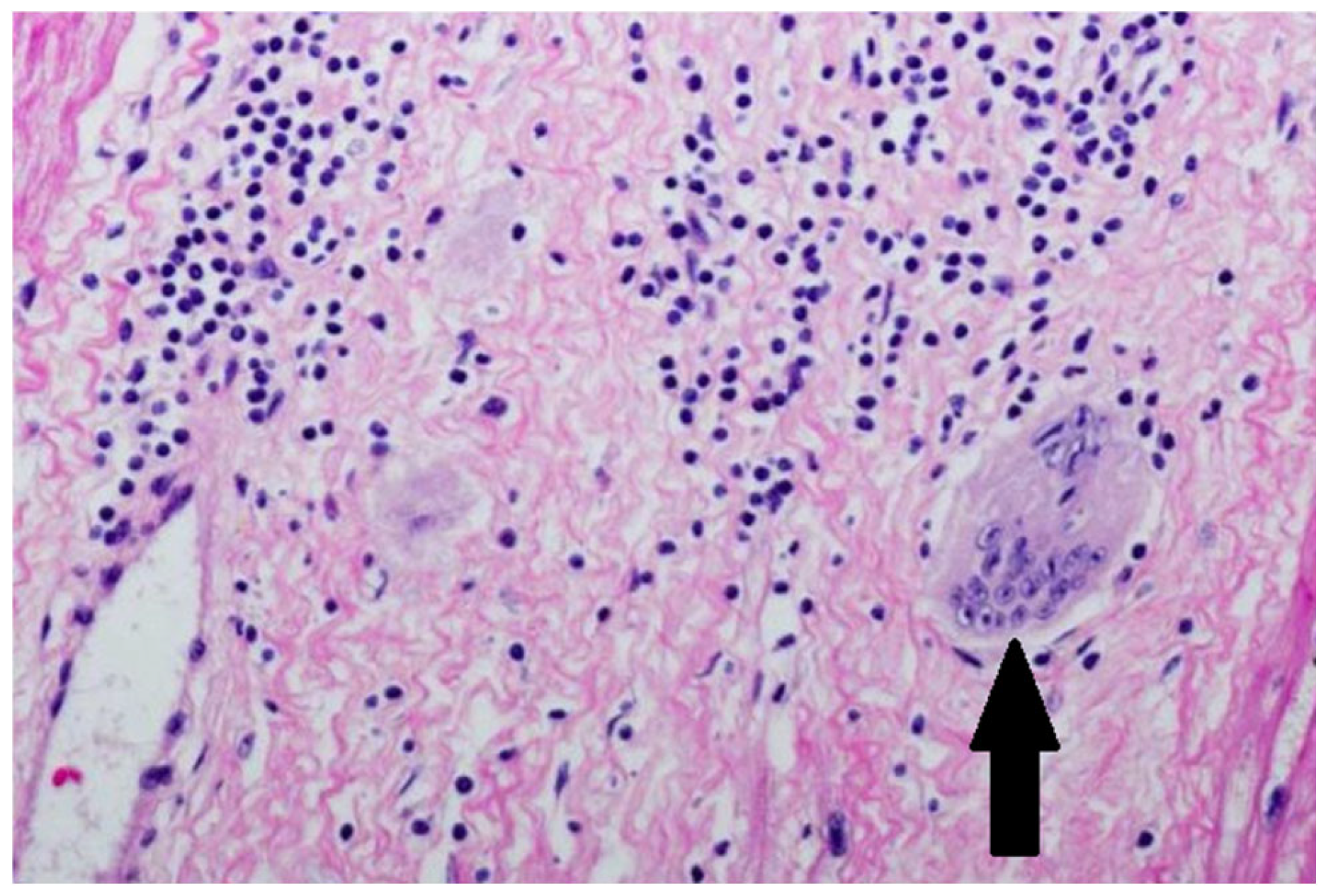

3. Case Presentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CS | Cardiac sarcoidosis |

| HF | Heart failure |

| ADHF | Acute decompensated heart failure |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association (functional class) |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| CRT-D | Cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator |

| ICD | Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| LV | Left ventricle/ventricular |

| RV | Right ventricle/ventricular |

| LVEDD | Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| TAPSE | Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

| TRVmax | Tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (maximum) |

| ACT | Acceleration time (pulmonary flow) |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| LGE | Late gadolinium enhancement |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| MSSA | Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus |

| ATP | Antitachycardia pacing |

References

- Bogdan, M.; Kanecki, K.; Tyszko, P.; Samel-Kowalik, P.; Goryński, P.; Barańska, A.; Nitsch-Osuch, A. Hospitalizations of patients with sarcoidosis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeyre, D.; Prasse, A.; Nunes, H.; Uzunhan, Y.; Brillet, P.Y.; Müller-Quernheim, J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2014, 383, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathai, S.V.; Patel, S.; Jorde, U.P.; Rochlani, Y. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Diagnosis of Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 2022, 18, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazitt, T.; Kharouf, F.; Feld, J.; Haddad, A.; Hijazi, N.; Kibari, A.; Fuks, A.; Sabo, E.; Mor, M.; Peleg, H.; et al. Real-Life Utilization of Criteria Guidelines for Diagnosis of Cardiac Sarcoidosis (CS). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.L.; O’Donnell, J.L.; Crozier, I. Prevalence, incidence and survival outcomes of cardiac sarcoidosis in the South Island, New Zealand. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 357, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnie, D.H.; Sauer, W.H.; Bogun, F.; Cooper, J.M.; Culver, D.A.; Duvernoy, C.S.; Judson, M.A.; Kron, J.; Mehta, D.; Cosedis Nielsen, J.; et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm 2014, 11, 1305–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, G.C.; Shaw, P.W.; Balfour, P.C., Jr.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Kramer, C.M.; Patel, A.R.; Salerno, M. Prognostic Value of Myocardial Scarring on CMR in Patients With Cardiac Sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulten, E.; Aslam, S.; Osborne, M.; Abbasi, S.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Blankstein, R. Cardiac sarcoidosis-state of the art review. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2016, 6, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen, J.; Uusitalo, V.; Pöyhönen, P.; Mäyränpää, M.I.; Kupari, M. Cardiac sarcoidosis: Phenotypes, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1495–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, K.; Lehtonen, J.; Nordenswan, H.K.; Mäyränpää, M.I.; Räisänen-Sokolowski, A.; Kandolin, R.; Simonen, P.; Pietilä-Effati, P.; Alatalo, A.; Utriainen, S.; et al. Sudden death in cardiac sarcoidosis: An analysis of nationwide clinical and cause-of-death registries. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3121–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamée, L.; Symons, R.; Degtiarova, G.; Dresselaers, T.; Gheysens, O.; Wuyts, W.; Van Cleemput, J.; Bogaert, J. Prognostic value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with biopsy-proven systemic sarcoidosis. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 3702–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, A.; Bray, J.J.H.; Tregidgo, L.; Ahmad, M.; Sharma, A.; Ng, A.; Siddiqui, A.; Khalid, A.A.; Hylton, K.; Ionescu, A.; et al. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement detected on cardiac magnetic resonance in cardiac sarcoidosis. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, T.; Okada, D.R.; Veillet-Chowdhury, M.; Bravo, P.E.; Mullins, E.; Hulten, E.; Agrawal, M.; Madan, R.; Taqueti, V.R.; Steigner, M.; et al. Complementary Value of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in the Assessment of Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, e007030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnie, D.H. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjepanovic, M.; Markovic, F.; Milivojevic, I.; Popevic, S.; Dimic-Janjic, S.; Popadic, V.; Zdravkovic, D.; Popovic, M.; Klasnja, A.; Radojevic, A.; et al. Contemporary Diagnostics of Cardiac Sarcoidosis: The Importance of Multimodality Imaging. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.R.; Cawley, P.J.; Heitner, J.F.; Klem, I.; Parker, M.A.; Jaroudi, W.A.; Meine, T.J.; White, J.B.; Elliott, M.D.; Kim, H.W.; et al. Detection of myocardial damage in patients with sarcoidosis. Circulation 2009, 17, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumi, J.E.; Taimeh, Z. Emerging Biomarkers in Cardiac Sarcoidosis and Other Inflammatory Cardiomyopathies. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2024, 21, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthals, D.; Bietenbeck, M.; Könemann, H.; Doldi, F.; Ventura, D.; Schäfers, M.; Mohr, M.; Wolfes, J.; Wegner, F.; Yilmaz, A.; et al. Cardiac Sarcoidosis-Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekir, S.A.; Yalcinsoy, M.; Gungor, S.; Tuncay, E.; Akyil, F.T.; Sucu, P.; Yavuz, D.; Boga, S. Prognostic value of inflammatory markers determined during diagnosis in patients with sarcoidosis: Chronic versus remission. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2021, 67, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, K.L.-Y.; Osman, A.R.; Yeoh, E.E.X.; Luangboriboon, J.; Lau, J.F.; Chan, J.J.A.; Yousif, M.; Tse, B.Y.H.; Horgan, G.; Gamble, D.T.; et al. Ultrafiltration versus Diuretics on Prognostic Cardiac and Renal Biomarkers in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segawa, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Nabeta, T.; Naruse, Y.; Kitai, T.; Yoshioka, K.; Tanaka, H.; Okumura, T.; Baba, Y.; Matsue, Y.; et al. Cortico-steroid therapy and long-term outcomes in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis stratified by left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. Open 2025, 10, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Buttar, C.; Lakhdar, S.; Pavankumar, T.; Guzman-Perez, L.; Mahmood, K.; Collura, G. Heart transplantation in end-stage heart failure secondary to cardiac sarcoidosis: An updated systematic review. Heart Fail. Rev. 2023, 28, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, K.C.; Youmans, Q.R.; Wu, T.; Harap, R.; Anderson, A.S.; Chicos, A.; Ezema, A.; Mandieka, E.; Ohiomoba, R.; Pawale, A.; et al. Heart transplantation outcomes in cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasaki, F.; Azuma, A.; Anzai, T.; Ishizaka, N.; Ishida, Y.; Isobe, M.; Inomata, T.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Eishi, Y.; Kitakaze, M.; et al. Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group. JCS 2016 Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiac—Digest Version. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 2329–238826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.Y.; Du, X.; Dong, J.Z. Re-evaluating serum angiotensin-converting enzyme in sarcoidosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 950095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurelings, L.E.M.; Miedema, J.R.; Dalm, V.A.S.H.; van Daele, P.L.A.; van Hagen, P.M.; van Laar, J.A.M.; Dik, W.A. Sensitivity and specificity of serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor for diagnosing sarcoidosis in a population of patients suspected of sarcoidosis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Day of Hospitalization | Clinical Symptoms and Events | Cardiac Rhythm Disturbances | Treatment/Procedures | Key Laboratory Abnormalities | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Severe dyspnea. orthopnea. peripheral edema | Sinus rhythm | IV diuretics. levosimendan | ↑ NT-proBNP (4.775 pg/mL). mild ↑ CRP (10 mg/L) | Admission. start HF treatment |

| 3 | Persistent dyspnea | Dobutamine started due to hypotension | Creatinine ↑ to 0.9 mg/dL NT-proBNP (1.647 pg/mL) | Hemodynamic instability | |

| 6 | Ascites. edema. worsening fatigue | Nonsustained VT | Furosemide + Opacorden | WBC ↑ (7.8 × 109/L)-normal. mild ↑ CRP (13.6 mg/L) | Planned myocardial biopsy |

| 8 | Dyspnea improving slightly | Occasional VT | Metypred 32 mg initiated | Creatinine ↑ to 1.0 mg/dL. NT-proBNP 5.708 pg/mL | Start of corticosteroids |

| 10 | Partial clinical improvement | Steroids ↑ to 40 mg | ↑ CRP (136 mg/L). ↑ PCT (7.59 ng/mL). ↑ creatinine (1.37 mg/dL) | MSSA bacteremia diagnosed | |

| 13 | Fluctuating dyspnea | IV cloxacillin started | CRP (11.1 mg/L) decreasing. WBC ↑ (8.5 × 109/L) normal | After antibiotics initiation | |

| 15 | Hallucinations. derealization | Ventricular arrhythmia episodes | Risperidone added | Creatinine stable (1.4 mg/dL). ↑ AST/ALT (306/172 U/L) | Steroid neuropsychiatric complications |

| 18 | Persistent fatigue | Continuation of therapy | ↑ NT-proBNP (11.173 pg/mL → upward trend) | Progressive HF | |

| 20 | Dyspnea. hypotension | Inotropes continued | NT-proBNP > 10.000 pg/mL | Advanced HF | |

| 23 | Worsening congestion | Furosemide intensified | WBC ↑ (29.2 × 109/L). CRP 1.435 mg/L. PCT 0.98 ng/mL | Sepsis progression | |

| 28 | Partial stabilization | Ongoing antibiotics | NT-proBNP 12.819 pg/mL. creatinine 0.78 mg/dL | Transient improvement | |

| 35 | Increasing fatigue. liver congestion | Supportive therapy | ↑ ALT 64 U/L. ↑ AST 73 U/L. ↑ bilirubin (1.8 mg/dL) | Liver dysfunction | |

| 39 | Dyspnea. edema | NT-proBNP 18.780 pg/mL. ↑ creatinine 1.07 mg/dL | Persistent HF | ||

| 48 | General deterioration | ↑ NT-proBNP 22.870 pg/mL. ↑ CRP 228.7 mg/L. ↑ GGT 124 U/L | Preterminal state | ||

| 54 | Cardiogenic shock and multiorgan failure. | Urgent HTx listing | NT-proBNP 11.005 pg/mL. creatinine 4.13 mg/dL. ↓ RBC (3.1 × 1012/L). ↓ Hb (9.8 g/dL) | Death during hospitalization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lucki, M.; Straburzyńska-Migaj, E.; Cofta, S.; Lesiak, M. Severe Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in a Patient with Cardiac Sarcoidosis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238462

Lucki M, Straburzyńska-Migaj E, Cofta S, Lesiak M. Severe Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in a Patient with Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238462

Chicago/Turabian StyleLucki, Mateusz, Ewa Straburzyńska-Migaj, Szczepan Cofta, and Maciej Lesiak. 2025. "Severe Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in a Patient with Cardiac Sarcoidosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238462

APA StyleLucki, M., Straburzyńska-Migaj, E., Cofta, S., & Lesiak, M. (2025). Severe Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in a Patient with Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238462