Impact of Coronary Function Testing on Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

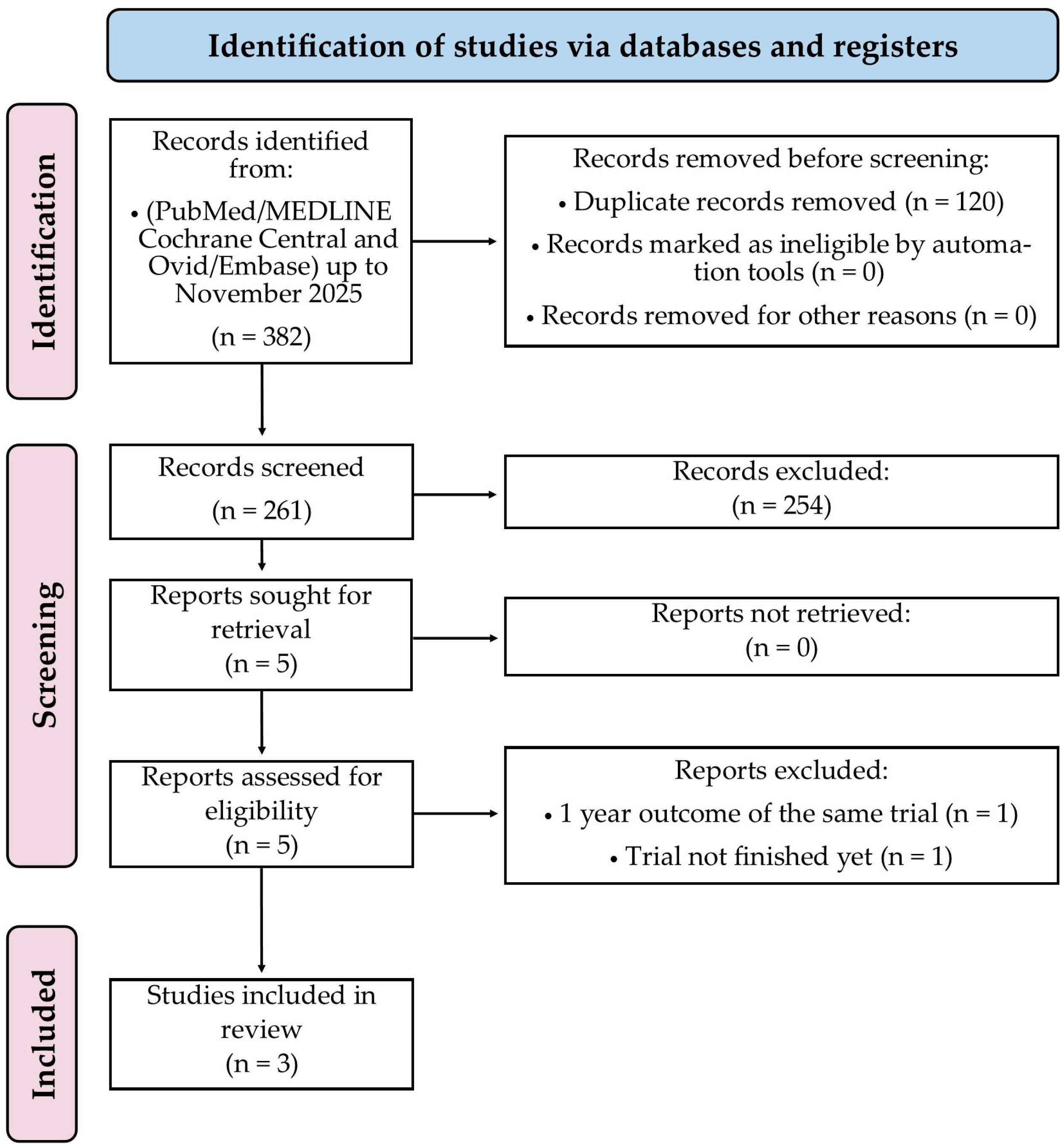

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Endpoints

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included RCTs

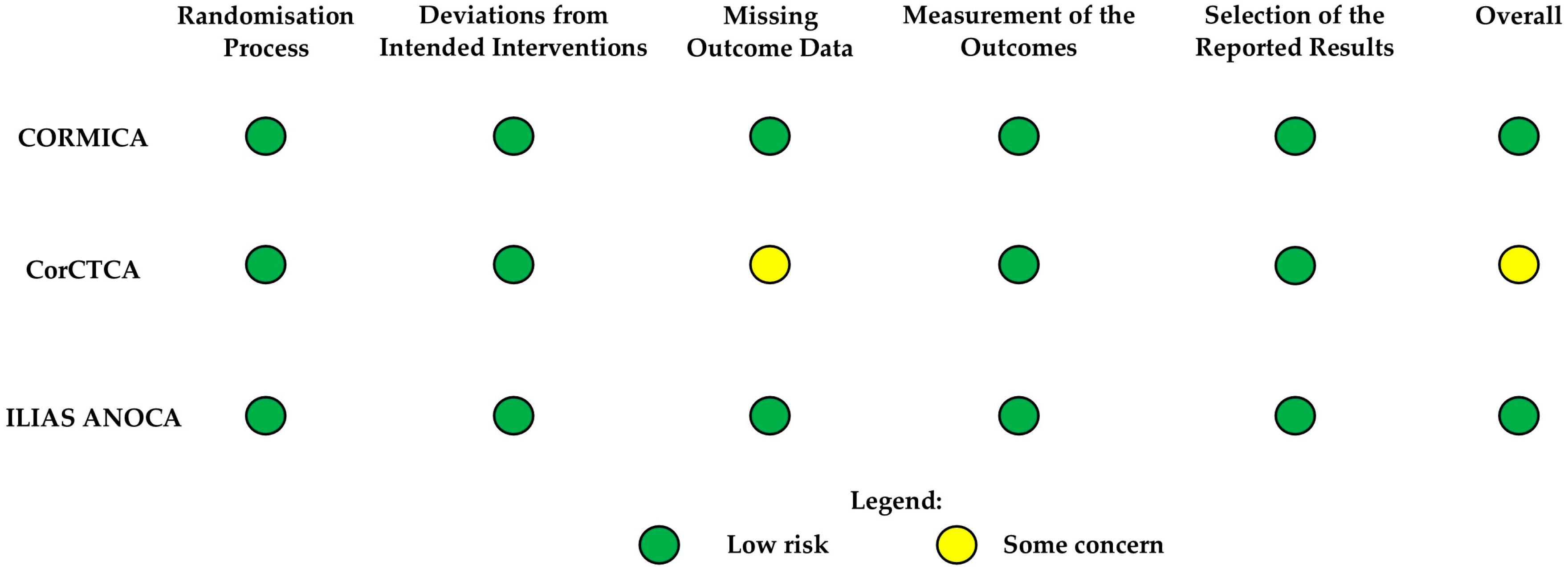

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.3. Prevalence of CMD Endotypes

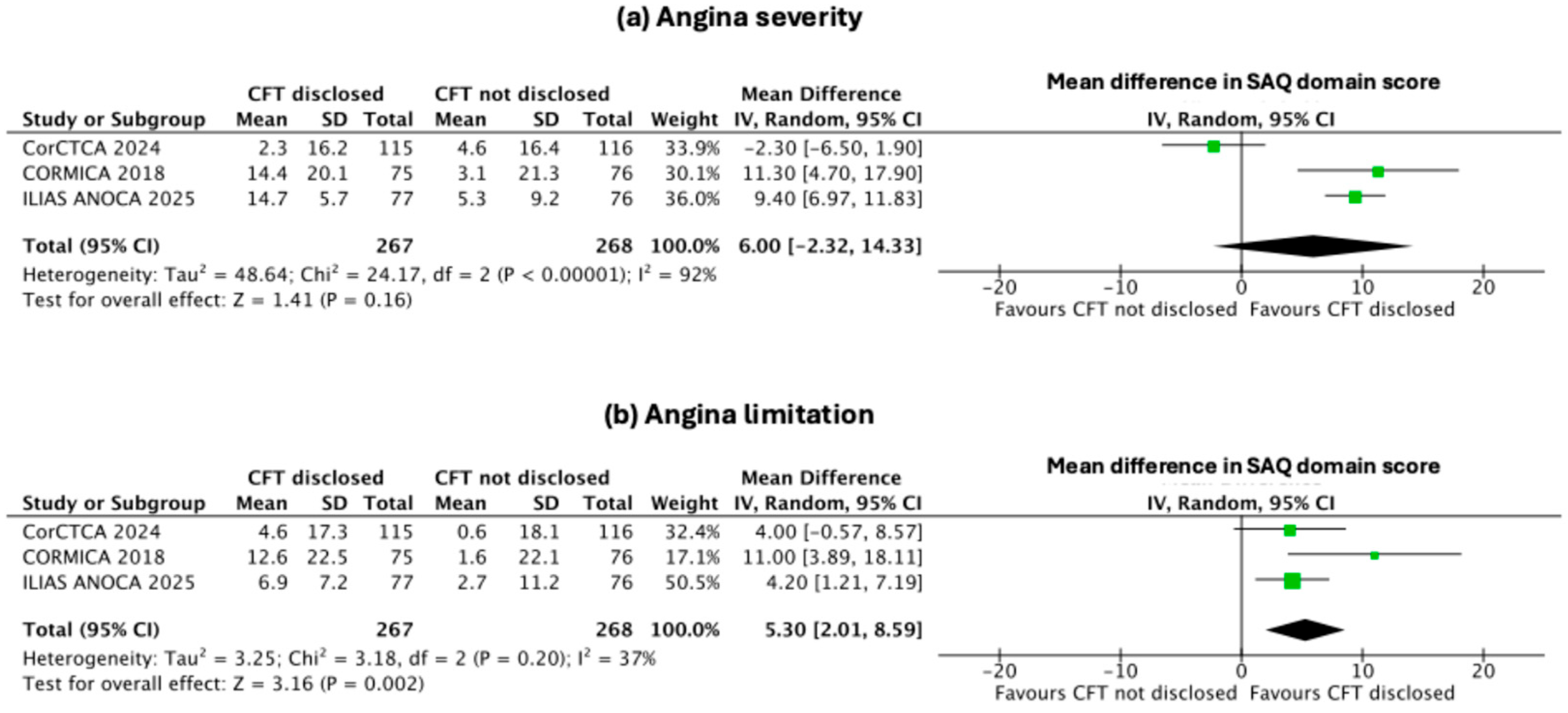

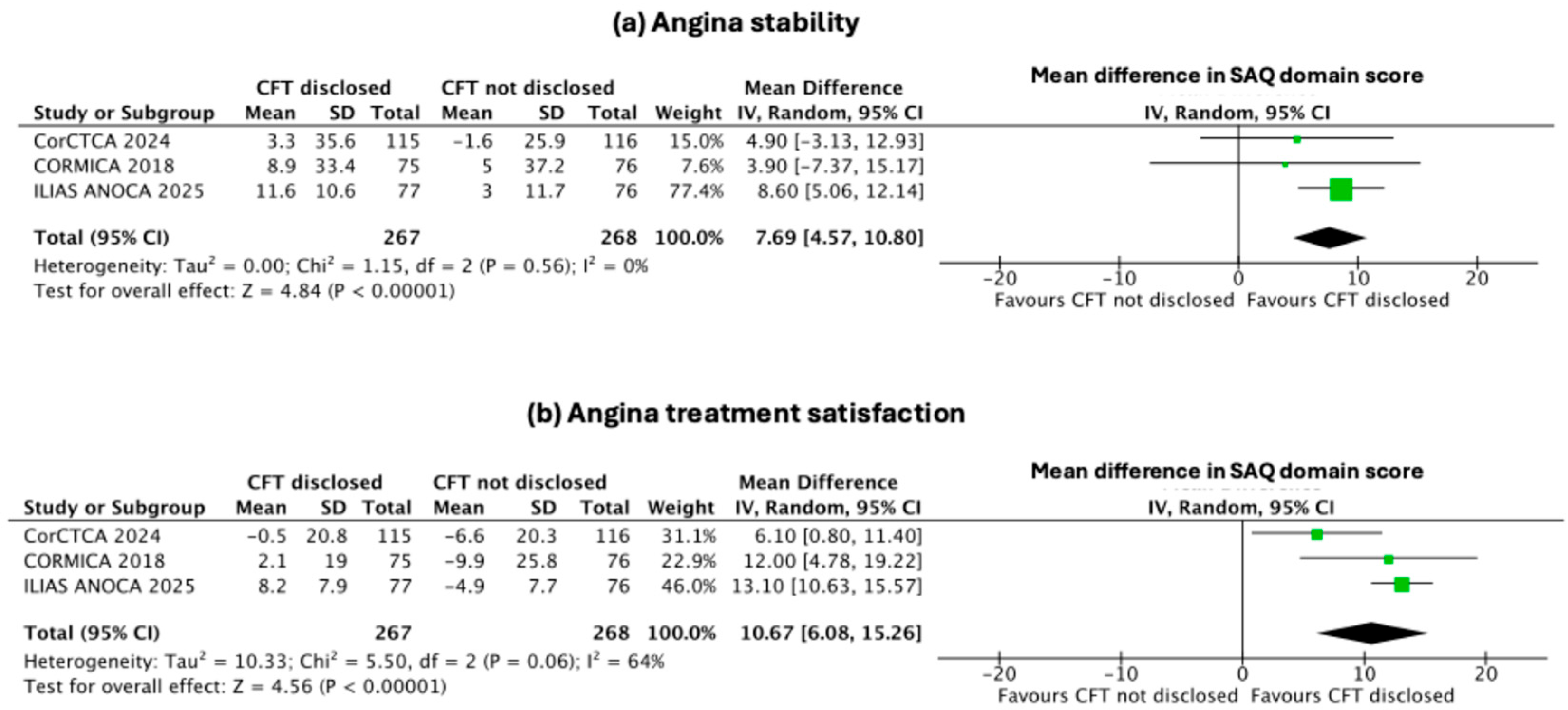

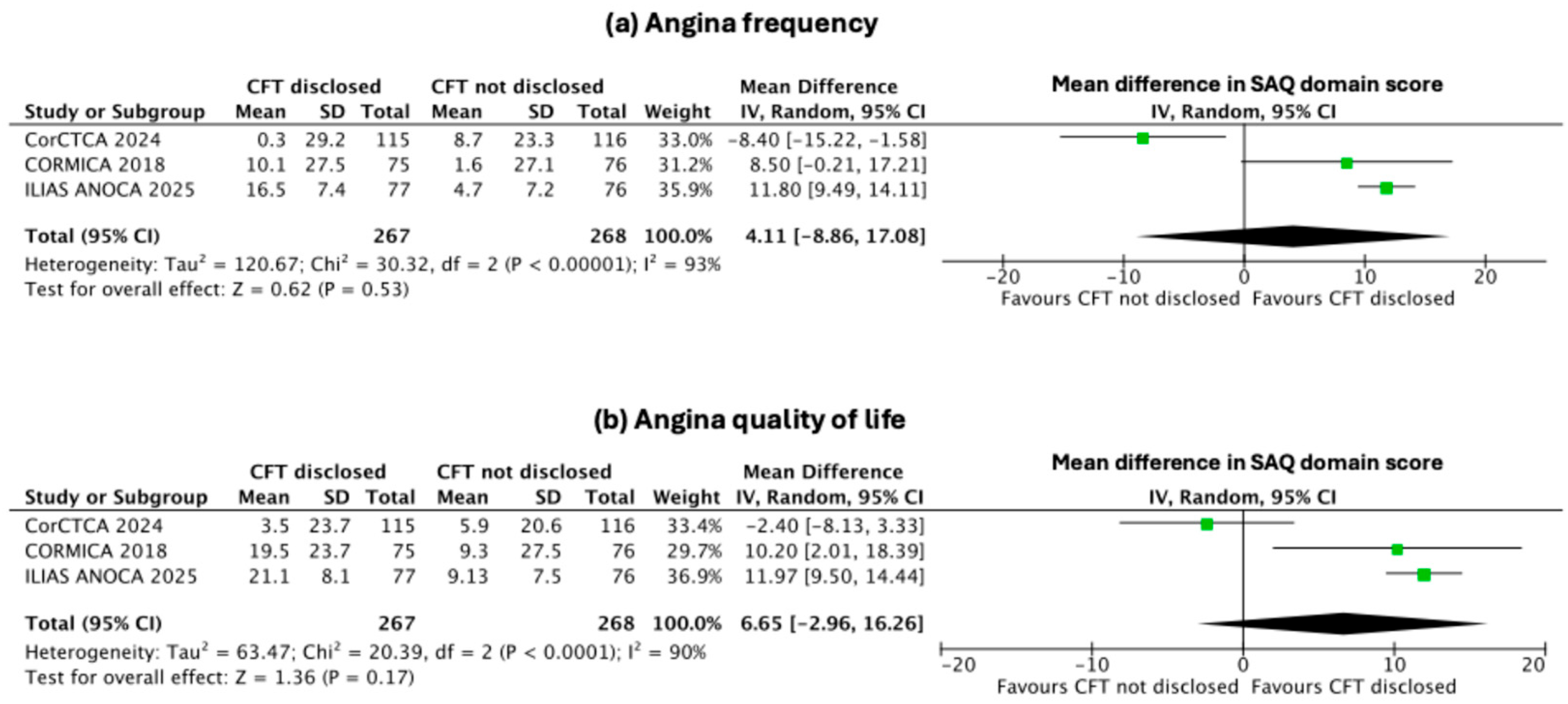

3.4. Secondary Endpoints: Change in Indices of Individual SAQ Domains

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Barriers to Clinical Application of CFT and Economic Implications

4.2. Future Direction

4.3. Emerging Non-Invasive Paradigms

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kunadian, V.; Chieffo, A.; Camici, P.G.; Berry, C.; Escaned, J.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; Prescott, E.; Karam, N.; Appelman, Y.; Fraccaro, C.; et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. EuroInterv. J. Eur. Collab. Work. Group Interv. Cardiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2021, 16, 1049–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, L.; Hvelplund, A.; Abildstrøm, S.Z.; Pedersen, F.; Galatius, S.; Madsen, J.K.; Jørgensen, E.; Kelbæk, H.; Prescott, E. Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, C.; Camici, P.G.; Crea, F.; George, M.; Kaski, J.C.; Ong, P.; Pepine, C.J.; Pompa, A.; Sechtem, U.; Shimokawa, H.; et al. Clinical standards in angina and non-obstructive coronary arteries: A clinician and patient consensus statement. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 429, 133162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camici, P.G.; Crea, F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 833–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, T.J.; Stanley, B.; Good, R.; Rocchiccioli, P.; McEntegart, M.; Watkins, S.; Eteiba, H.; Shaukat, A.; Lindsay, M.; Robertson, K.; et al. Stratified Medical Therapy Using Invasive Coronary Function Testing in Angina: The CorMicA Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2841–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidik, N.P.; Stanley, B.; Sykes, R.; Morrow, A.J.; Bradley, C.P.; McDermott, M.; Ford, T.J.; Roditi, G.; Hargreaves, A.; Stobo, D.; et al. Invasive Endotyping in Patients With Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation 2024, 149, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boerhout, C.K.M.; Namba, H.F.; Liu, T.; Beijk, M.A.M.; Damman, P.; Meuwissen, M.; Ong, P.; Sechtem, U.; Appelman, Y.; Berry, C.; et al. Coronary function testing vs angiography alone to guide treatment of angina with non-obstructive coronary arteries: The ILIAS ANOCA trial. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4396–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, C.; Sidik, N.P.; McEntegart, M.B.; Cor, C.T.A.I. Response by Berry et al. to Letter Regarding Article, “Invasive Endotyping in Patients With Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial”. Circulation 2024, 150, e5–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heggie, R.; Briggs, A.; Stanley, B.; Good, R.; Rocchiccioli, P.; McEntegart, M.; Watkins, S.; Eteiba, H.; Shaukat, A.; Lindsay, M.; et al. Stratified medicine using invasive coronary function testing in angina: A cost-effectiveness analysis of the British Heart Foundation CorMicA trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 337, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, T.P.J.; Konst, R.E.; de Vos, A.; Paradies, V.; Teerenstra, S.; van den Oord, S.C.H.; Dimitriu-Leen, A.; Maas, A.; Smits, P.C.; Damman, P.; et al. Efficacy of Diltiazem to Improve Coronary Vasomotor Dysfunction in ANOCA: The EDIT-CMD Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Rahman, H.; Douiri, A.; Demir, O.M.; De Silva, K.; Clapp, B.; Webb, I.; Gulati, A.; Pinho, P.; Dutta, U.; et al. ChaMP-CMD: A Phenotype-Blinded, Randomized Controlled, Cross-Over Trial. Circulation 2024, 149, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taqueti, V.R.; Di Carli, M.F. Coronary Microvascular Disease Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2625–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, C.P.; Orchard, V.; McKinley, G.; Heggie, R.; Wu, O.; Good, R.; Watkins, S.; Lindsay, M.; Eteiba, H.; McGowan, J.; et al. The coronary microvascular angina cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging trial: Rationale and design. Am. Heart J. 2023, 265, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taqueti, V.R. Prevalence of Abnormal Coronary Function in Patients With Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease on Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography: Insights From the CorCTA Trial. Circulation 2024, 149, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Jones, P.G.; Arnold, S.V.; Spertus, J.A. Interpretation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire as an Outcome Measure in Clinical Trials and Clinical Care: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial | Total Number of Patients and Country | Study Design/ Intervention | Diagnostic Method | Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Classification | Follow up Duration | Primary End-point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORMICA | n = 151 United Kingdom | Randomised, open-label, stratified by invasive coronary function testing vs. usual care | Invasive coronary angiography with CFR, IMR (thermodilution method), and acetylcholine provocation testing | Inclusion criteria: • Adults with angina and non-obstructive coronary arteries (≤50% stenosis) • Positive stress test or clinical indication for invasive angiography Exclusion criteria: • Obstructive CAD (>50%) • Prior CABG or PCI • Significant LV dysfunction • Contraindication to adenosine or acetylcholine | Isolated microvascular angina (52%), isolated vasospastic angina (17%), mixed (21%) | 6 months | Improvement in angina symptoms (SAQ score) comparing stratified vs. usual care |

| CorCTCA | n = 231 United Kingdom | Prospective, multicentre diagnostic study comparing CT-FFR and CT perfusion against invasive testing | CT angiography and invasive CFR, IMR (thermodilution method), and acetylcholine provocation testing | Inclusion criteria: • Adults referred for CT coronary angiography for stable chest pain • No flow-limiting stenosis Exclusion criteria: • Obstructive CAD (>50%) • Acute coronary syndrome • Prior revascularisation • Contraindication to adenosine or contrast | Isolated microvascular angina (55%), isolated vasospastic angina (12%), mixed (7%) | 6 months (primary follow-up; additional analyses at 12 and ≥18 months) | Accuracy of CT-based functional testing (CT-FFR and CT perfusion) compared with invasive coronary testing |

| ILIAS ANOCA | n = 153 Netherlands and Germany | Multicentre, prospective registry evaluating invasive vasomotor testing in ANOCA patients | Invasive vasomotor testing with CFR, hMR (Doppler method), and stepwise acetylcholine provocation testing | Inclusion criteria: • Consecutive ANOCA patients with angiographically non-obstructive coronaries • Stable symptoms suitable for invasive testing Exclusion criteria: • Obstructive CAD (>50%) • Acute coronary syndrome • Major comorbidities limiting testing • Pregnancy • Contraindication to acetylcholine or adenosine | Isolated microvascular angina (7%), isolated vasospastic angina (42%), mixed (20%) | 6 months | Prevalence and prognostic impact of invasive endotypes (CMD, vasospasm, mixed) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habtezghi, T.; Haq, A.; Jin, Y.; Haq, N.; Bulluck, H. Impact of Coronary Function Testing on Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238461

Habtezghi T, Haq A, Jin Y, Haq N, Bulluck H. Impact of Coronary Function Testing on Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238461

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabtezghi, Temar, Adam Haq, Yanbo Jin, Nimrah Haq, and Heerajnarain Bulluck. 2025. "Impact of Coronary Function Testing on Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238461

APA StyleHabtezghi, T., Haq, A., Jin, Y., Haq, N., & Bulluck, H. (2025). Impact of Coronary Function Testing on Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238461