The Hidden Burden of Sexual Dysfunction and Healthcare Service Gaps in Tunisian Spinal Cord Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

n = (1.96)2 × 0.80(1 − 0.80)/(0.11)2 = 3.8416 × 0.16/0.0121 = 50.8 ≈ 51

2.3. Population

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Assessment Tools

2.5.1. Demographic and Clinical Assessment

2.5.2. Pain Assessment Tools

2.5.3. Functional Independence Assessment

2.5.4. Psychological Status Assessment

2.5.5. Sleep Quality Evaluation

2.5.6. Male Sexual Function Assessment Questionnaire

2.5.7. Female Sexual Function Assessment Questionnaire

2.5.8. Sexual Health Communication Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Use of GenAI in Writing

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Injury Characteristics and Clinical Profile

3.3. Pain Assessment and Complications

3.4. Functional Status Assessment

3.5. Psychological and Sleep Quality Assessment

3.6. Male Sexual Function Assessment

3.7. Female Sexual Function Assessment

3.8. Associated Factors with Sexual Dysfunction: Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

3.8.1. Univariate Analysis

3.8.2. Multivariate Analysis

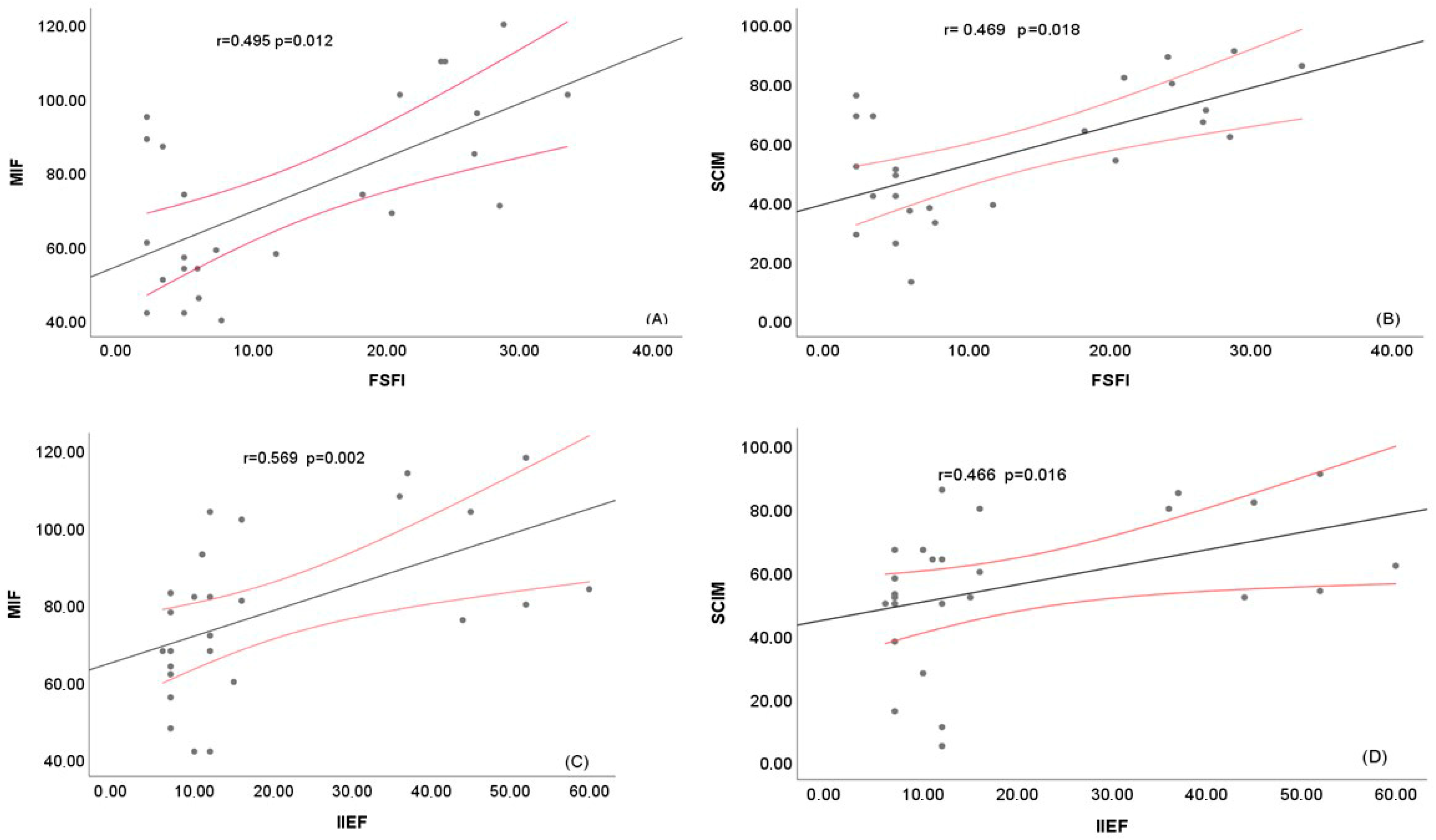

3.8.3. Correlation Analyses

3.9. Sexual Health Communication and Service Access

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2016 Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Burden of Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury, 1990-2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 56–87. [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Hu, S.; Wang, P.; Kang, H.; Peng, R.; Dong, Y.; Li, F. Spinal Cord Injury: The Global Incidence, Prevalence, and Disability from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Spine 2022, 47, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Tetreault, L.; Kalsi-Ryan, S.; Nouri, A.; Fehlings, M.G. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 6, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosrati Nejad, F.; Basakha, M.; Charkazi, A.; Esmaeili, A. Exploring Barriers to Rehabilitation for Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury: A Qualitative Study in Iran. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Lim, J.; Mekary, R.A.; Rattani, A.; Dewan, M.C.; Sharif, S.Y.; Osorio-Fonseca, E.; Park, K.B. Traumatic Spinal Injury: Global Epidemiology and Worldwide Volume. World Neurosurg. 2018, 113, e345–e363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakoshi, N.; Suda, K.; Kudo, D.; Sakai, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Mikami, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Tokioka, T.; Tokuhiro, A.; Takei, H.; et al. A Nationwide Survey on the Incidence and Characteristics of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Japan in 2018. Spinal Cord. 2021, 59, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.D.; Campbell, R.R.; Sabharwal, S.; Nelson, A.L.; Palacios, P.A.; Gavin-Dreschnack, D. Health Care Costs for Patients with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury in the Veterans Health Administration. J. Spinal Cord. Med. 2007, 30, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, H.; Noonan, V.K.; Trenaman, L.M.; Joshi, P.; Rivers, C.S. The Economic Burden of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Canada. Chronic Dis. Inj. Can. 2013, 33, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.D.; Borisoff, J.F.; Johnson, R.D.; Stiens, S.A.; Elliott, S.L. The Impact of Spinal Cord Injury on Sexual Function: Concerns of the General Population. Spinal Cord. 2007, 45, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.; Birkhäuser, V.; Courtois, F.; Gül, M.; Ibrahim, E.; Kiekens, C.; New, P.W.; Ohl, D.A.; Fode, M. Sexual and Reproductive Health in Neurological Disorders: Recommendations from the Fifth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine (ICSM 2024). Sex. Med. Rev. 2025, 13, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groat, W.C.; Yoshimura, N. Anatomy and Physiology of the Lower Urinary Tract. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 130, 61–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monga, M.; Bernie, J.; Rajasekaran, M. Male Infertility and Erectile Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury: A Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 80, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.S.; Aisen, C.M.; Alexander, S.M.; Aisen, M.L. Sexual Concerns after Spinal Cord Injury: An Update on Management. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 41, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, G.; Del Popolo, G.; Macchiarella, A.; Mencarini, M.; Celso, M. Sexual Rehabilitation in Women with Spinal Cord Injury: A Critical Review of the Literature. Spinal Cord. 2010, 48, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipski, M.L.; Alexander, C.J.; Rosen, R. Sexual Arousal and Orgasm in Women: Effects of Spinal Cord Injury. Ann. Neurol. 2001, 49, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Aplin, T.; Setchell, J. Sexuality Support After Spinal Cord Injury: What Is Provided in Australian Practice Settings? Sex. Disabil. 2022, 40, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassem, M.; Siddiqui, M.; Wunder, S.; Ganshorn, K.; Kraushaar, J. Sexual Health Counselling in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: Health Care Professionals’ Perspectives. J. Spinal Cord. Med. 2022, 45, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, S.; Kendall, M.; Fronek, P.; Miller, D.; Geraghty, T. Training the Interdisciplinary Team in Sexuality Rehabilitation Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Needs Assessment. Sex. Disabil. 2003, 21, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.J.; Hough, S. Impact of Spinal Cord Injury on Sexuality: Broad-Based Clinical Practice Intervention and Practical Application. J. Spinal Cord. Med. 2012, 35, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunna, T.; Elias, E.; Summaka, M.; Zein, H.; Elias, C.; Nasser, Z. Quality of Life among Men with Spinal Cord Injury in Lebanon: A Case Control Study. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 45, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earle, S.; O’Dell, L.; Davies, A.; Rixon, A. Views and Experiences of Sex, Sexuality and Relationships Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature. Sex. Disabil. 2020, 38, 567–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torriani, S.B.; Britto, F.C.; da Silva, G.A.; de Oliveira, D.C.; de Figueiredo Carvalho, Z.M. Sexuality of People with Spinal Cord Injury: Knowledge, Difficulties and Adaptation. J. Biomed. Sci. Eng. 2014, 7, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migaou, H.; Youssef, I.B.H.; Boudokhane, S.; Kilani, M.; Jellad, A.; Frih, Z.B.S. Sexual disorders among spinal cord injury patients. Prog. Urol. 2018, 28, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazaeipour, Z.; Taheri-Otaghsara, S.-M.; Naghdi, M. Depression Following Spinal Cord Injury: Its Relationship to Demographic and Socioeconomic Indicators. Top. Spinal Cord. Inj. Rehabil. 2015, 21, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.C.; Leiblum, S.R.; Spector, I.P. Psychologically Based Treatment for Male Erectile Disorder: A Cognitive-Interpersonal Model. J. Sex. Marital. Ther. 1994, 20, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegel, M.; Meston, C.; Rosen, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Cross-Validation and Development of Clinical Cutoff Scores. J. Sex. Marital. Ther. 2005, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, S.M.; Hough, S.; Boyd, B.L.; Hill, J. Men’s Adjustment to Spinal Cord Injury: The Unique Contributions of Conformity to Masculine Gender Norms. Am. J. Mens. Health 2010, 4, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo Cuenca, A.I.; Sampietro-Crespo, A.; Virseda-Chamorro, M.; Martín-Espinosa, N. Psychological Impact and Sexual Dysfunction in Men with and without Spinal Cord Injury. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giusto, M.L.; Ertl, M.M.; Ramos-Usuga, D.; Carballea, D.; Degano, M.; Perrin, P.B.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C. Sexual Health and Sexual Quality of Life Among Individuals With Spinal Cord Injury in Latin America. Top. Spinal Cord. Inj. Rehabil. 2023, 29, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Vahedi, M.; Rahimzadeh, M. Sample Size Calculation in Medical Studies. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2013, 6, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, J.; Albo, M.; Dunn, K.; Joseph, A. Spinal Cord Injury and Sexuality in Married or Partnered Men: Activities, Function, Needs, and Predictors of Sexual Adjustment. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2001, 30, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzanos, I.-A.; Tzitzika, M.; Nianiarou, M.; Konstantinidis, C. Sexual Dysfunction in Women with Spinal Cord Injury Living in Greece. Spinal Cord. Ser. Cases 2021, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmani, Z.; Khoei, E.S.M.; Aghajani, N.; Bayat, A. Sexual Matters of Couples with Spinal Cord Injury Attending a Sexual Health Clinic in Tehran, Iran. Arch. Neurosci. 2018, 6, e83940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASIA and ISCoS International Standards Committee The 2019 Revision of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI)-What’s New? Spinal Cord. 2019, 57, 815–817. [CrossRef]

- Calmels, P.; Mick, G.; Perrouin-Verbe, B.; Ventura, M.; SOFMER (French Society for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation). Neuropathic Pain in Spinal Cord Injury: Identification, Classification, Evaluation. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 52, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, A.W.; Michael Linacre, J.; Wright, B.D.; Hamilton, B.B.; Granger, C. Measurement Characteristics of the Functional Independence Measure. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 1994, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itzkovich, M.; Gelernter, I.; Biering-Sorensen, F.; Weeks, C.; Laramee, M.T.; Craven, B.C.; Tonack, M.; Hitzig, S.L.; Glaser, E.; Zeilig, G.; et al. The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM) Version III: Reliability and Validity in a Multi-Center International Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 1926–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolrich, R.A.; Kennedy, P.; Tasiemski, T. A Preliminary Psychometric Evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in 963 People Living with a Spinal Cord Injury. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelleri, J.C.; Rosen, R.C.; Smith, M.D.; Mishra, A.; Osterloh, I.H. Diagnostic Evaluation of the Erectile Function Domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology 1999, 54, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, T.H.; Gheit, S.A.; Saied, H.S.; Al kherbash, S.A. Arabic Translation of Female Sexual Function Index and Validation in an Egyptian Population. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 3370–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddour, M.; Ammar, M.; Fatma, L.B.; Ceylan, H.İ.; Loubiri, I.; El Feni, N.; Jemni, S.; Puce, L.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Dergaa, I. Stifled Motivation, Systemic Neglect: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Inactivity in Post-Chemotherapy Cancer Survivors in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Cancers 2025, 17, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, F.; Hultling, C.; El Masry, W.S.; Smith, M.D.; Osterloh, I.H.; Orr, M.; Maytom, M. Randomized Trial of Sildenafil for the Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury. Sildenafil Study Group. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 46, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipski, M.L.; Rosen, R.C.; Alexander, C.J.; Gómez-Marín, O. Sexual Responsiveness in Women with Spinal Cord Injuries: Differential Effects of Anxiety-Eliciting Stimulation. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2004, 33, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.S.; Samsó, J.V. Specific Aspects of Erectile Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2004, 16 (Suppl. S2), S42–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiaghababaei, M.; Javidan, A.N.; Saberi, H.; Khoei, E.M.; Khalifa, D.A.; Koenig, H.G.; Pakpour, A.H. Female Sexual Dysfunction in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Study from Iran. Spinal Cord. 2014, 52, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charfi, A.; Ben Salah, R.; Frikha, O.; Mahfoudh, N.; Kamoun, A.; Bouattour, Y.; Gaddour, L.; Hakim, F.; Bahloul, Z.; Makni, H. HLA Polymorphisms in South Tunisian Systemic Sclerosis Patients: A Case–Control Study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2025, 44, 4053–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihab, C.; Sawssan, D.; Najeh, S.; Salma, S.; Nadia, B.; Sonda, M.K.; Nouha, F.; Mariem, D.; Mohamed, M.; Mhiri, C. Sexual Dysfunctions and Self-Esteem in Multiple Sclerosis: A Tunisian Study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 71, 104335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, A.; Alaranta, H.T.; Kautiainen, H.; Kotila, M. Sexual Activity and Satisfaction in Men with Traumatic Spinal Cord Lesion. J. Rehabil. Med. 2007, 39, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.; Lude, P.; Taylor, N. Quality of Life, Social Participation, Appraisals and Coping Post Spinal Cord Injury: A Review of Four Community Samples. Spinal Cord. 2006, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffi, I.; Affes, M. La santé sexuelle et reproductive en Tunisie. Institutions médicales, lois et itinéraires thérapeutiques des femmes après la révolution. L’Année Maghreb. 2017, 17, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.; Rogers, B.A. Anxiety and Depression after Spinal Cord Injury: A Longitudinal Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, J.; Glass, C.A.; Owens, R.G.; Soni, B.M. Factors Associated with Sexual Functioning in Women Following Spinal Cord Injury. Paraplegia 1995, 33, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavese, C.; Kessler, T.M. Prediction of Lower Urinary Tract, Sexual, and Bowel Function, and Autonomic Dysreflexia after Spinal Cord Injury. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramp, J.D.; Courtois, F.J.; Ditor, D.S. Sexuality for Women with Spinal Cord Injury. J. Sex. Marital. Ther. 2015, 41, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVivo, M.J.; Fine, P.R. Spinal Cord Injury: Its Short-Term Impact on Marital Status. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1985, 66, 501–504. [Google Scholar]

- Sramkova, T.; Skrivanova, K.; Dolan, I.; Zamecnik, L.; Sramkova, K.; Kriz, J.; Muzik, V.; Fajtova, R. Women’s Sex Life After Spinal Cord Injury. Sex. Med. 2017, 5, e255–e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Rahnama, P.; Saberi, H.; Saffari, M.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V.; Burri, A.; Hajiaghababaei, M. The Relationship between Anxiety, Depression and Religious Coping Strategies and Erectile Dysfunction in Iranian Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 2016, 54, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Population | Male Patients (n = 26) | Female Patients (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, Mean ± SD | 43.47 ± 15.43 | 42.04 ± 15.08 | 44.16 ± 15.86 |

| Marital status, N (%) | |||

| Married | 33 (64.7) | 15 (57.7) | 18 (72) |

| Single | 18 (35.3) | 11 (42.3) | 7 (28) |

| Residence, N (%) | |||

| Urban | 34 (66.7) | 16 (61.5) | 18 (72) |

| Rural | 17 (33.3) | 10 (38.5) | 7 (28) |

| Socioeconomic level, N (%) | |||

| Low | 15 (29.4) | 8 (30.8) | 7 (28) |

| Medium | 31 (60.8) | 14 (53.8) | 17 (68) |

| Good | 5 (9.8) | 4 (15.4) | 1 (4) |

| Comorbid conditions, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 6 (11.8) | 4 (15.4) | 2(8) |

| No | 45 (88.2) | 22 (84.6) | 23 (92) |

| Smoking, N (%) | 19 (37.3) | 18 (69.2) | 1 (4) |

| Characteristics | Population (n = 51) | Male Patients (n = 26) | Female Patients (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time since injury, months, median, [IQR] | 22 [13–36] | 16 [13–29.25] | 29 [18–37] |

| Etiology, N (%) | |||

| Traumatic | 37 (72.5) | 18 (69.2) | 19(76) |

| Non-traumatic | 14 (27.5) | 8 (30.8) | 6 (24) |

| NLI, N (%) | |||

| Cervical | 22 (43.1) | 11 (42.3) | 11 (44) |

| Dorsal | 19 (37.3) | 9 (34.6) | 10 (40) |

| Above T10 | 31 (60.8) | 16 (61.5) | 15 (60) |

| Lumbar | 10 (19.6) | 6 (23.1) | 4 (16) |

| AIS, N (%) | |||

| A | 15 (29.4) | 8 (30.8) | 7 (28) |

| B | 6 (11.8) | 4 (15.4) | 2 (8) |

| C | 16 (31.4) | 8 (30.8) | 8 (32) |

| D | 14 (27.5) | 6 (23.1) | 8 (32) |

| N | Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erectile function | 26 | 1 | [1–12.25] |

| Orgasmic function | 26 | 1 | [1–6.5] |

| Sexual desire | 26 | 3.5 | [3–5.25] |

| Intercourse satisfaction | 26 | 3 | [0–4.75] |

| Overall satisfaction | 26 | 2.5 | [2–6] |

| IIEF | 26 | 12 | [7–36.25] |

| Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|

| FSFI | 7.2 | [4–24.25] |

| FSFI desire | 1.2 | [1.2–4.5] |

| FSFI arousal | 0.8 | [0–4.5] |

| FSFI lubrication | 1.5 | [0–4.05] |

| FSFI orgasm | 2 | [0–3.2] |

| FSFI satisfaction | 3.6 | [1–4.8] |

| FSFI pain | 0 | [0–3.6] |

| Variable | Value | Sexual Dysfunction No (n = 8) | Sexual Dysfunction Yes (n = 43) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Median, SD | 40.7 ± 14.8 | 43.5 ± 15.5 | 0.645 | |

| Marital Status N (%) | Married | 6 (18.2) | 27 (81.8) | 0.696 |

| Single | 2 (11.1) | 16 (88.9) | ||

| Residence N (%) | Urban | 5 (14.7) | 29 (85.3) | 1.000 |

| Rural | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) | ||

| Socioeconomic level N (%) | Low | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) | 0.213 |

| Medium, | 4 (11.1) | 32 (88.9) | ||

| Good | ||||

| Comorbidities N (%) | Yes | - | 6 (14) | 0.572 |

| Smoking N (%) | yes | 2(25) | 17(39.5) | 0.694 |

| Etiology | Traumatic | 5 (13.5) | 32 (86.5) | 0.668 |

| Non traumatic | 3 (21.4) | 11 (78.6) | ||

| Time since injury Median [IQR] | 33.5 [13–70.5] | 20 [13–36] | 0.491 | |

| AIS N (%) | complete | - | 15 (34.9) | 0.087 |

| incomplete | 8 (100) | 28 (65.1) | ||

| Level D10 | Above D10 | 4 (50) | 27 (62.8) | 0.696 |

| Below D10 | 4 (50) | 16 (37.2) | ||

| Urinary Incontinence N (%) | - | 16 (37.2) | 0.045 | |

| Pressure ulcers N (%) | 1 (12.5) | 11 (25.6) | 0.662 | |

| NHO N (%) | - | 9 (20.9) | 0.322 | |

| NRS [IQR] | 4.5 [0.75–5.75] | 4 [2–6] | 0.895 | |

| DN4 [IQR] | 3 [1–6.5] | 3 [2–5] | 0.979 | |

| HAD-S A [IQR] | 7.5 [6–9] | 6 [5–9] | 0.183 | |

| HAD-S D [IQR] | 6.5 [4.5–9.75] | 7 [4–9] | 0.794 | |

| SCIM-III [IQR] | 69 [62–89.75] | 52 [38–69] | 0.010 | |

| FIM Mean, SD | 94.38 ± 17.77 | 72.79 ± 21.80 | 0.011 | |

| PSQI Mean, SD | 8.12 ± 5.41 | 6.79 ± 2.66 | 0.855 |

| Erectile Function | Orgasmic Function | Sexual Desire | Intercourse Satisfaction | Overall Satisfaction | IIEF Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | r | −0.118 | −0.21 | −0.223 | 0.012 | −0.085 | −0.064 |

| p-value | 0.565 | 0.304 | 0.273 | 0.955 | 0.681 | 0.756 | |

| Time since injury | r | −0.371 | −0.432 | −0.312 | −0.17 | −0.151 | −0.192 |

| p-value | 0.062 | 0.027 | 0.121 | 0.405 | 0.461 | 0.346 | |

| NRS | r | −0.263 | −0.376 | −0.297 | −0.274 | −0.186 | −0.287 |

| p-value | 0.194 | 0.059 | 0.141 | 0.176 | 0.364 | 0.155 | |

| DN4 | r | −0.245 | −0.326 | −0.264 | −0.355 | −0.228 | −0.225 |

| p-value | 0.228 | 0.104 | 0.192 | 0.075 | 0.262 | 0.27 | |

| HAD-S A | r | 0.35 | 0.423 | 0.333 | 0.407 | 0.053 | 0.303 |

| p-value | 0.08 | 0.031 | 0.097 | 0.039 | 0.797 | 0.133 | |

| HAD-S D | r | −0.038 | −0.093 | −0.016 | 0.101 | 0.088 | 0.134 |

| p-value | 0.855 | 0.652 | 0.938 | 0.623 | 0.668 | 0.515 | |

| SCIM-III | r | 0.529 | 0.457 | 0.377 | 0.129 | 0.55 | 0.466 |

| p-value | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.058 | 0.531 | 0.004 | 0.016 | |

| FIM | r | 0.609 | 0.552 | 0.501 | 0.29 | 0.565 | 0.569 |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.151 | 0.003 | 0.002 | |

| PSQI | r | 0.028 | 0.019 | −0.267 | 0.183 | −0.083 | −0.073 |

| p-value | 0.892 | 0.927 | 0.188 | 0.37 | 0.685 | 0.724 |

| Desire | Arousal | Lubrication | Orgasm | Satisfaction | Pain | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | r | 0.071 | 0.085 | 0.144 | 0.244 | 0.045 | 0.076 | 0.191 |

| p-value | 0.738 | 0.687 | 0.491 | 0.24 | 0.833 | 0.716 | 0.36 | |

| Time since injury | r | 0.45 | 0.369 | 0.362 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.287 | 0.39 |

| p-value | 0.024 | 0.069 | 0.075 | 0.119 | 0.131 | 0.165 | 0.054 | |

| NRS | r | 0.002 | 0.017 | −0.015 | 0.099 | −0.049 | −0.116 | 0.1 |

| p-value | 0.993 | 0.936 | 0.945 | 0.638 | 0.817 | 0.582 | 0.635 | |

| DN4 | r | 0.162 | 0.258 | 0.226 | 0.274 | 0.06 | 0.212 | 0.183 |

| p-value | 0.44 | 0.214 | 0.278 | 0.186 | 0.774 | 0.309 | 0.381 | |

| HAD-S anxiety | r | 0.256 | 0.261 | 0.229 | 0.316 | 0.21 | 0.137 | 0.284 |

| p-value | 0.217 | 0.207 | 0.27 | 0.124 | 0.314 | 0.513 | 0.169 | |

| HAD-S depression | r | −0.027 | 0.163 | 0.079 | 0.227 | −0.003 | −0.053 | 0.184 |

| p-value | 0.899 | 0.438 | 0.706 | 0.275 | 0.988 | 0.802 | 0.379 | |

| SCIM-III | r | 0.664 | 0.536 | 0.564 | 0.492 | 0.508 | 0.683 | 0.469 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.018 | |

| FIM | r | 0.666 | 0.557 | 0.589 | 0.509 | 0.482 | 0.648 | 0.495 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.012 | |

| PSQI | r | −0.164 | −0.092 | −0.173 | −0.022 | −0.188 | −0.142 | −0.097 |

| p-value | 0.433 | 0.662 | 0.407 | 0.917 | 0.369 | 0.498 | 0.646 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loubiri, I.; Dergaa, I.; Hajji, H.; Ceylan, H.İ.; Gaddour, M.; Dridi, N.; Ghali, H.; Stefanica, V.; Jemni, S. The Hidden Burden of Sexual Dysfunction and Healthcare Service Gaps in Tunisian Spinal Cord Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8380. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238380

Loubiri I, Dergaa I, Hajji H, Ceylan Hİ, Gaddour M, Dridi N, Ghali H, Stefanica V, Jemni S. The Hidden Burden of Sexual Dysfunction and Healthcare Service Gaps in Tunisian Spinal Cord Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8380. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238380

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoubiri, Ines, Ismail Dergaa, Habib Hajji, Halil İbrahim Ceylan, Mariem Gaddour, Nourhene Dridi, Hela Ghali, Valentina Stefanica, and Sonia Jemni. 2025. "The Hidden Burden of Sexual Dysfunction and Healthcare Service Gaps in Tunisian Spinal Cord Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8380. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238380

APA StyleLoubiri, I., Dergaa, I., Hajji, H., Ceylan, H. İ., Gaddour, M., Dridi, N., Ghali, H., Stefanica, V., & Jemni, S. (2025). The Hidden Burden of Sexual Dysfunction and Healthcare Service Gaps in Tunisian Spinal Cord Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8380. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238380