Bullous Wells’ Syndrome: Case Report and Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

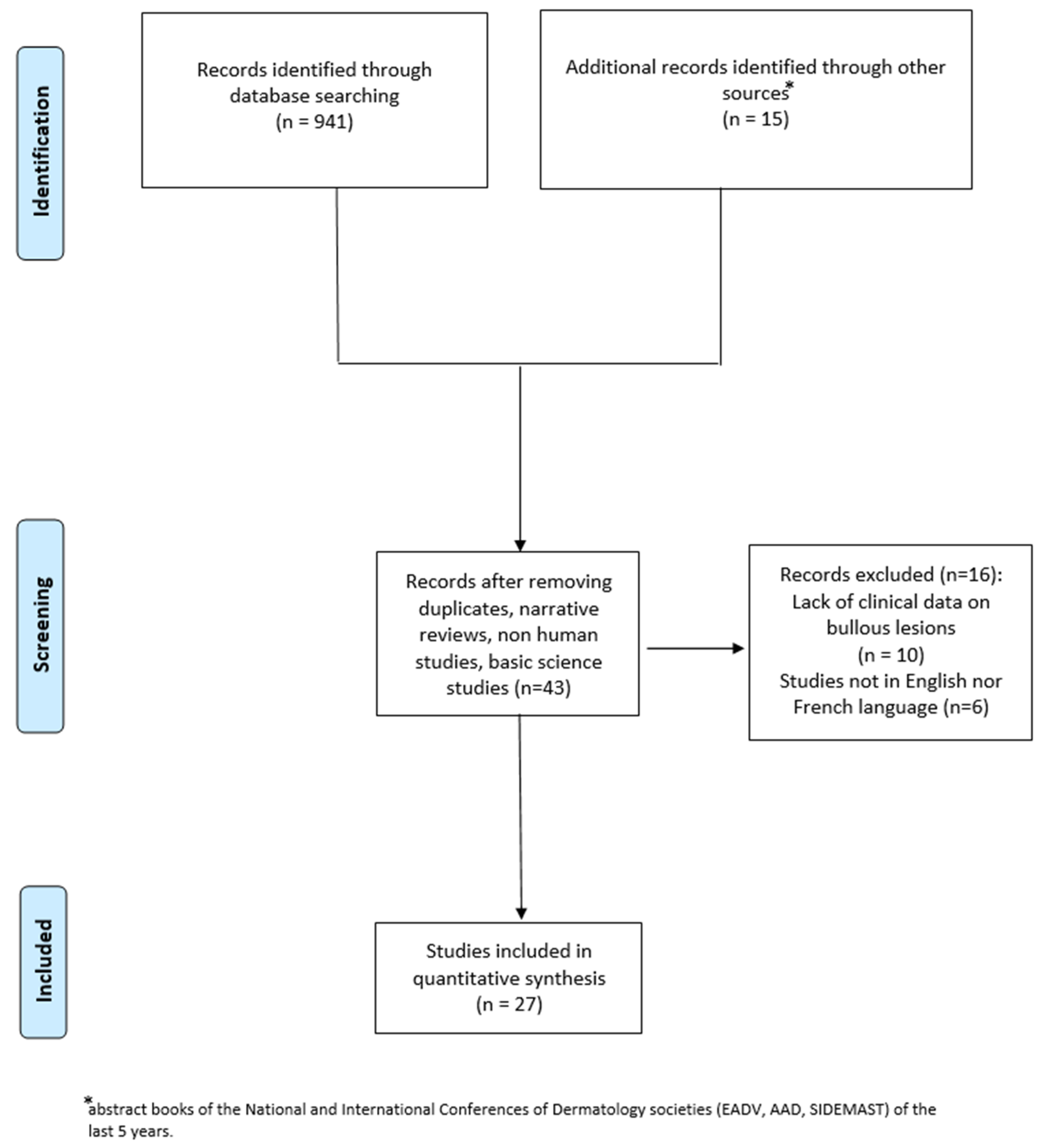

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

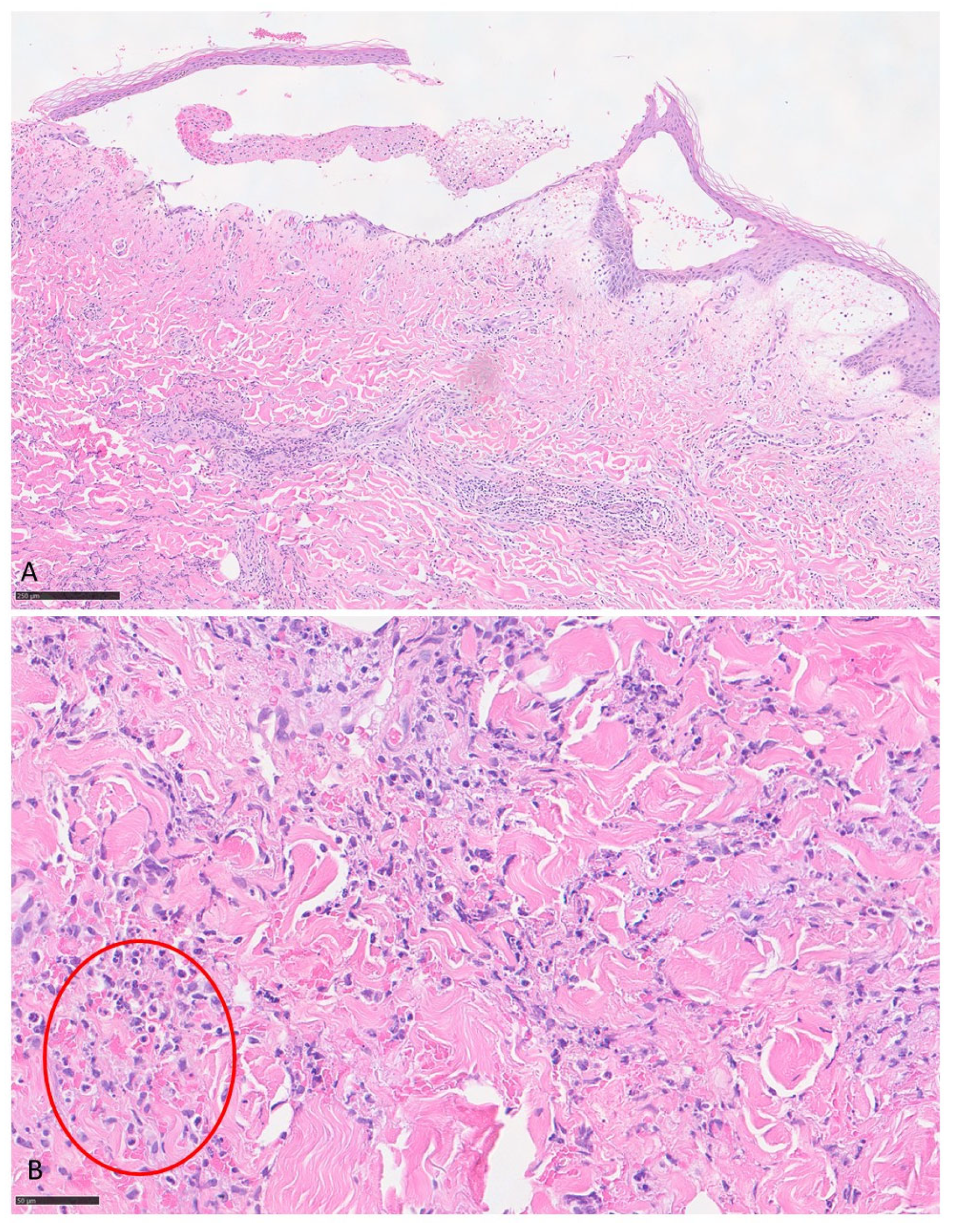

3.1. Case Report

3.2. Systematic Literature Review

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WS | Wells’ syndrome |

| BWS | Bullous Wells’ syndrome |

| IL | Interleukin |

| DRESS | Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms |

| BP | Bullous pemphigoid |

References

- Long, H.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Lu, Q. Eosinophilic Skin Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 50, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, A.V.; Genovese, G. Eosinophilic Dermatoses: Recognition and Management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, R.; Marzano, A.V.; Vezzoli, P.; Lunardon, L. Wells syndrome in adults and children: A report of 19 cases. Arch. Dermatol. 2006, 142, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weins, A.B.; Biedermann, T.; Weiss, T.; Weiss, J.M. Wells syndrome. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2016, 14, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Frigerio, E.; Cozzi, A.; Garutti, C.; Garavaglia, M.; Altomare, G. Bullous Wells’ syndrome associated with non-Hodgkin’s lymphocytic lymphoma. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2008, 88, 530–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciani, C.; Motta, A.; Tortorella, R.; De Benedetto, A.; Amerio, P.; Tulli, A. Bullous Wells syndrome. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2006, 20, 1021–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peckruhn, M.; Elsner, P.; Tittelbach, J. Bullous Wells Syndrome. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Bae, K.N.; Son, J.H.; Shin, K.; Kim, H.; Ko, H.-C.; Kim, B.; Kim, M.-B. Bullous Wells Syndrome Induced by Ustekinumab. Ann. Dermatol. 2023, 35, S180–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmo, A.; Filippi, F.; Pileri, A.; Misciali, C.; Bardazzi, F. Bullous Wells Syndrome: A needle in the haystack. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 60, e150–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, J.A. Wells Syndrome with Bullous Lesions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017, 5, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.E.; Ng, S.K.; Thng, S.T. Bullous Presentation of Idiopathic Wells Syndrome (Eosinophilic Cellulitis). Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2017, 46, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoulis, A.C.; Bozi, E.; Samara, M.; Kalogeromitros, D.; Panayiotides, I.; Stavrianeas, N.G. Idiopathic bullous eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome). Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 34, e375–e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams, M.; Hudgens, J.; Lesher, J.L., Jr.; Florentino, F. Wells’ syndrome presenting as a noninfectious bullous cellulitis in a child. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2012, 29, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Singal, A.; Sharma, S. Idiopathic bullous eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome) responsive to topical tacrolimus and antihistamine combination. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2012, 78, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, T.; Watanabe, H.; Sueki, H. Bullous eosinophilic cellulitis with subcorneal pustules. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2015, 81, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soua, Y.; Akkari, H.; Sriha, B.; Belhadjali, H.; Zili, J. Lésions bulleuses des poignets [Bullous lesions on the wrists]. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 141, 717–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuttelaar, M.L.; Jonkman, M.F. Bullous eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) associated with Churg-Strauss syndrome. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2003, 17, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, A.E.; Bruckner, A.L.; Howard, R.M.; Lee, B.P.; Wu, S.; Frieden, I.J. Bullous “cellulitis” with eosinophilia: Case report and review of Wells’ syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics 2005, 116, e149–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.H.; Shin, M.K. Bullous Eosinophilic Cellulitis in a Child Treated with Dapsone. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2013, 30, e46–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, M.C.; Janin-Mercier, A.; Souteyrand, P.; Bourges, M.; Hermier, C. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome): Ultrastructural study of a case with circulating immune complexes. Dermatologica 1988, 176, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçkin, D.; Demirhan, B. Drugs and Wells’ syndrome: A possible causal relationship? Int. J. Dermatol. 2001, 40, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arca, E.; Köse, O.; Karslioğlu, Y.; Taştan, H.B.; Demïrïz, M. Bullous eosinophilic cellulitis succession with eosinophilic pustular folliculitis without eosinophilia. J. Dermatol. 2007, 34, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, T.C.; Antony, F.; Holden, C.A.; Al-Dawoud, A.; Coulson, I. Two cases of bullous eosinophilic cellulitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 146, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X. Bullous Wells syndrome in a patient with occult nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.W.; Chow, E.Y. Breaking the Blister: A Case Report of Bullous Wells’ Syndrome Resolved with Oral Terbinafine. Cureus 2025, 17, e80060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarese, G.; Rosato, W.A.; Drago, F.; Meduri, A.R.; Ambrogio, F.; De Marco, A.; Cazzato, G.; Foti, C. Bullous Wells’ Syndrome Successfully Treated with Omalizumab. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Papaetis, G.S.; Politou, V.N.; Panagiotou, S.M.; Georghiou, A.A.; Antonakas, P.D. Recurrent Cellulitis-Like Episodes of the Lower Limbs and Acute Diarrhea in a 30-Year-Old Woman: A Case Report. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e932732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Cogorno, L.; Agnoletti, A.F.; Ciccarese, G.; Parodi, A. A retrospective study of cutaneous drug reactions in an outpatient population. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 37, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Merlo, G.; Trave, I.; Javor, S.; Rebora, A.; Parodi, A. Oral and cutaneous manifestations of viral and bacterial infections: Not only COVID-19 disease. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 39, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Agnoletti, A.F.; Sarocchi, F.; Parodi, A. Neuro sweet syndrome: A systematic review. A rare complication of Sweet syndrome. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2017, 117, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, F.; Herzum, A.; Ciccarese, G.; Broccolo, F.; Rebora, A.; Parodi, A. Acute pain and postherpetic neuralgia related to Varicella zoster virus reactivation: Comparison between typical herpes zoster and zoster sine herpete. J. Med. Virol. 2019, 91, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heelan, K.; Ryan, J.F.; Shear, N.H.; Egan, C.A. Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): Proposed diagnostic criteria and a literature review of the drug-induced variant. J. Dermatol. Case Rep. 2013, 7, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinig, B.; Vojvocic, A.; Lotti, T.; Tirant, M.; Wollina, U. Wells Syndrome—An Odyssey. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 3002–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarese, G.; Broccolo, F.; Rebora, A.; Parodi, A.; Drago, F. Oropharyngeal lesions in pityriasis rosea. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 833–837.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plötz, S.G.; Abeck, D.; Behrendt, H.; Simon, H.U.; Ring, J. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome). Hautarzt 2000, 51, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.; Kim, D.Y. Chronic relapsing eosinophilic cellulitis associated, although independent in severity, with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambichler, T.; Othlinghaus, N.; Rotterdam, S.; Altmeyer, P.; Stücker, M. Impetiginized Wells’ syndrome in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 34, e274–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.P.; Carvalho, S.D.; Ferreira, O.; Brito, C. Wells syndrome associated with lung cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coattrenec, Y.; Ibrahim Yasmine, L.; Harr, T.; Spoerl, D.; Jandus, P. Long-term Remission of Wells Syndrome With Omalizumab. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 30, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeland, Ø.; Balieva, F.; Undersrud, E. Wells syndrome: A case of successful treatment with omalizumab. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 994–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.P.; Giménez-Arnau, A.M.; Saini, S.S. Mechanisms of action that contribute to efficacy of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy 2017, 72, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Takenaka, M.; Matsunaga, Y.; Okada, S.; Anan, S.; Yoshida, H.; Ra, C. High affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI) expression on eosinophils infiltrating the lesions and mite patch tested sites in atopic dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1995, 287, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messingham, K.N.; Holahan, H.M.; Frydman, A.S.; Fullenkamp, C.; Srikantha, R.; A Fairley, J. Human eosinophils express the high affinity IgE receptor, FcεRI, in bullous pemphigoid. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perotin, J.M.; Barnig, C. Mécanismes d’action de l’omalizumab: Au-delà de l’action anti-IgE [Omalizumab: Beyond anti-IgE properties]. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2017, 34, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terhorst-Molawi, D.; Altrichter, S.; Röwert, J.; Magerl, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Maurer, M.; Bergmann, K.C.; Metz, M. Effective treatment with mepolizumab in a patient with refractory Wells syndrome. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2020, 18, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herout, S.; Bauer, W.M.; Schuster, C.; Stingl, G. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome) successfully treated with mepolizumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Country | Age | Sex | Blood Eosinophils (Cells/µL) (%) | Other Cutaneous Signs | Involved Sites | Skin Symptoms | Mucosal Involvement | Systemic Involvement | Comorbidities | Histological Flames Figures | Possible Trigger | Time from Trigger to Eruption | Treatment | Outcome | Follow up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our patient | Italy | 90 | F | WNR | vesicles | Limbs | itching | no | no | chronic lymphocytic leukemia | yes | chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 2 years | oral steroid (prednisolone 25 mg/day), mometasone furoate cream (twice daily) | relapsing disease then remission | 6 |

| Bao et al. (2025) [26] | Canada | 52 | F | 1100 | macules, papules | feet | itching | INR | INR | epilepsy and osteoarthrosis | yes | tinea pedis, onychomycosis | - | oral terbinafine (250 mg/day) for 3 months; ciclopirox cream, bilastine (40 mg twice day), prednisone(30 mg/day) for five days | remission | 18 |

| Ciccarese et al. (2025) [27] | Italy | 36 | F | 1770 (18%) | urticarial plaques, vesicles | trunk, lower limbs | itching | no | no | no | yes | - | - | Oral steroid (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/day), Omalizumab 300 mg/4 weeks | remission | 36 |

| Peckruhn et al. (2019) [8] | Germany | 5 | F | 8850 | plaques, nodules | Feet | Pain | INR | INR | INR | yes | Insect bite | 14–21 days | Oral steroid (prednisolone 100 mg/day), dapsone (50 mg/day), dimetindene twice daily | remission | <1 |

| Kim et al. (2023) [9] | Sud Korea | 64 | F | WNR | patches | Left limbs | Itching/burning sensation | INR | INR | Psoriasis | yes | Ustekinumab | 10 days | Drug discontinuation | remission | INR |

| Papaetis et al. (2021) [28] | Cyprus | 30 | F | WNR | papules, nodules, plaques, urticaria, vesicles | left lower limb | itching | INR | fever | C. difficile intestinal infection | yes | intestinal infection | - | mometasone furoate cream (twice day), levocetirizine (10 mg day) for 1 month | remission | 24 |

| Guglielmo et al. (2020) [10] | Italy | 82 | M | WNR | patches, plaques, pustules | Limbs | INR | INR | INR | no | yes | - | - | Oral methylprednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day) | remission | INR |

| Guglielmo et al. (2020) [10] | Italy | 70 | F | WNR | plaques | Limbs | Pain | INR | INR | Diabetes | yes | Insect bite | 7 days | Oral methylprednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day) | remission | INR |

| Lieberman JA (2017) [11] | Tennessee | 11 | M | 730 | patches, plaques | Lower limb | INR | INR | INR | INR | INR | Insect bite | 2 days | Oral steroids, topical mupirocin | remission | INR |

| Feliciani et al. (2006) [7] | Italy | 88 | F | WNR | plaques, vesicles | trunk, folds, limbs | Itching/burning sensation | INR | INR | Colon carcinoma | INR | colon carcinoma | 10 months | Oral methylprednisolone (40 mg/day) | remission | 36 |

| Lim et al. (2017) [12] | Singapore | 44 | F | 810 | papules, plaques, vesicles | face, trunk, upper limbs | Itching | INR | no | no | INR | - | - | Oral prednisolone (20 mg/day) | remission | 6 |

| Katoulis et al. (2009) [13] | Greece | 64 | F | 700 | plaques, vesicles | neck | Itching | INR | INR | Uterine fibromyomas, osteoporosis | no | - | - | Topical steroid | remission | 12 |

| Shams et al. (2012) [14] | Louisiana | 11 | F | 3129 (21%) | plaques, erosions, crusts | face, neck, upper limbs | Itching | INR | Fever | no | yes | Insect bite | 1 month | Intravenous steroid | INR | INR |

| Verma et al. (2012) [15] | India | 40 | M | WNR | plaques, vesicles | trunk, upper limbs | Itching | no | no | no | yes | - | - | Oral antihistamine, topical tacrolimus | remission | 6 |

| Kamiyama et al. (2015) [16] | Japan | 39 | F | 1260 (15%) | plaques, vesicles, pustules | trunk, upper and lower limbs | Itching, tenderness | INR | no | no | yes | - | - | Oral prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day), fexofenadine 60 mg twice daily, topical steroid | remission | 6 |

| Soua et al. (2014) [17] | Tunisia | 61 | F | WNR | vesicles | upper limbs | Itching | no | no | no | yes | - | - | Oral prednisolone (40 mg/day), antihistamine 10 mg/day | remission | INR |

| Spinelli et al. (2008) [5] | Italy | 73 | F | 1740 (14.3%) | purpura | lower limbs | Itching | INR | Fever, lymph node swelling | sigma adenocarcinoma 2 years earlier | yes | Small-cell non-Hodgkin’s B lymphoma | concomitant diagnosis | Oral methylprednisolone (20 mg/day), antihistamine, topical fusidic acid cream | remission | INR |

| Schuttelaar et al. (2003) [18] | Netherlands | 55 | M | 5780 (34%) | plaques, vesicles, purpura | limbs | Itching, pain | INR | Malaise, fever, arthralgia | Nasal polyposis, asthma, peripheral eosinophilia | yes | Churg-Strauss syndrome | - | Intravenous dexamethasone (200 mg for 3 days), Doxycycline (100 mg twice daily), cyclophosphamide (150 mg/day) | remission | INR |

| Gilliam et al. (2005) [19] | USA | 1 | F | 14,400 (48%) | plaques | lower limbs | Itching | INR | no | no | yes | - | - | Oral steroid (2 mg/kg), topical steroid | remission | 12 |

| Moon et al. (2013) [20] | Sud Korea | 9 | M | 4770 (24.5%) | vesicles | trunk, limbs | Itching | INR | no | no | yes | Upper respiratory infection | 21 days | Oral prednisolone (40 mg/day), cetirizine, dapsone, topical steroid | remission | INR |

| Caputo et al. (2006) [3] | Italy | 64 | F | (32%) | no | trunk, lower extremities | INR | INR | INR | no | no | - | - | Oral betamethasone sodium phosphate (4 mg/day), oral amoxicillin | remission | 120 |

| Caputo et al. (2006) [3] | Italy | 34 | F | (19%) | plaques | face | INR | INR | INR | no | no | - | - | Oral betamethasone sodium phosphate (4 mg/day), ceftriaxone sodium (2 g/day) | relapsing disease | 60 |

| Ferrier et al. (1988) [21] | France | 42 | F | 1460 (8%) | plaques | face, trunk, upper limbs | Itching | INR | no | INR | yes | lincomycin, thiopental, acetylsalicylic c acid, pholcodine | - | Oral betamethasone (8 mg/day), dapsone | relapsing disease then remission | 48 |

| Seçkin et al. (2001) [22] | Turkey | 28 | F | 990 (16.5%) | papules, vesicles, crusts | Limbs | Itching | INR | INR | INR | yes | tenoxicam and diclofenac sodium and/or amoxicillin | - | Oral prednisolone(40 mg/day) | remission | INR |

| Arca et al. (2007) [23] | Turkey | 20 | M | WNR | vesicles, pustules, plaques | limbs | Itching | INR | no | no | yes | - | - | Oral prednisone (60 mg/kg), tetracycline 500 mg twice daily | remission | 12 |

| Ling et al. (2002) [24] | UK | 45 | F | 6180 (46.5%) | plaques | face, trunk, upper limbs | INR | INR | no | no | no | - | - | Oral prednisolone (30 mg/day), cetirizine (10 mg twice day) | remission | 12 |

| Ling et al. (2002) [24] | UK | 42 | M | WNR | plaques | face, limbs | Pain | tongue, throat | Influenza-like illness | INR | yes | - | - | Oral prednisolone(40 mg/day) | lost to follow-up | lost to follow up |

| Li M et al. (2025) [25] | China | 58 | M | 750 | papules, plaques, vesicles | neck, trunk, upper limbs | INR | INR | fever, lymph node swelling | nasopharynx carcinoma | yes | nasopharynx carcinoma | concomitant diagnosis | Oral prednisone (15 mg/day) | remission | INR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciccarese, G.; Sbarra, G.; Liguori, G.; Cazzato, G.; Rosato, W.A.; Meduri, A.R.; Lospalluti, L.; De Marco, A.; Filotico, R.; Bonamonte, D.; et al. Bullous Wells’ Syndrome: Case Report and Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238370

Ciccarese G, Sbarra G, Liguori G, Cazzato G, Rosato WA, Meduri AR, Lospalluti L, De Marco A, Filotico R, Bonamonte D, et al. Bullous Wells’ Syndrome: Case Report and Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238370

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiccarese, Giulia, Giorgia Sbarra, Giovanni Liguori, Gerardo Cazzato, William Andrew Rosato, Alexandre Raphael Meduri, Lucia Lospalluti, Aurora De Marco, Raffaele Filotico, Domenico Bonamonte, and et al. 2025. "Bullous Wells’ Syndrome: Case Report and Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238370

APA StyleCiccarese, G., Sbarra, G., Liguori, G., Cazzato, G., Rosato, W. A., Meduri, A. R., Lospalluti, L., De Marco, A., Filotico, R., Bonamonte, D., Drago, F., & Foti, C. (2025). Bullous Wells’ Syndrome: Case Report and Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238370