Clinical Nursing Management of Adult Patients with Delirium in a Hospital Setting—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

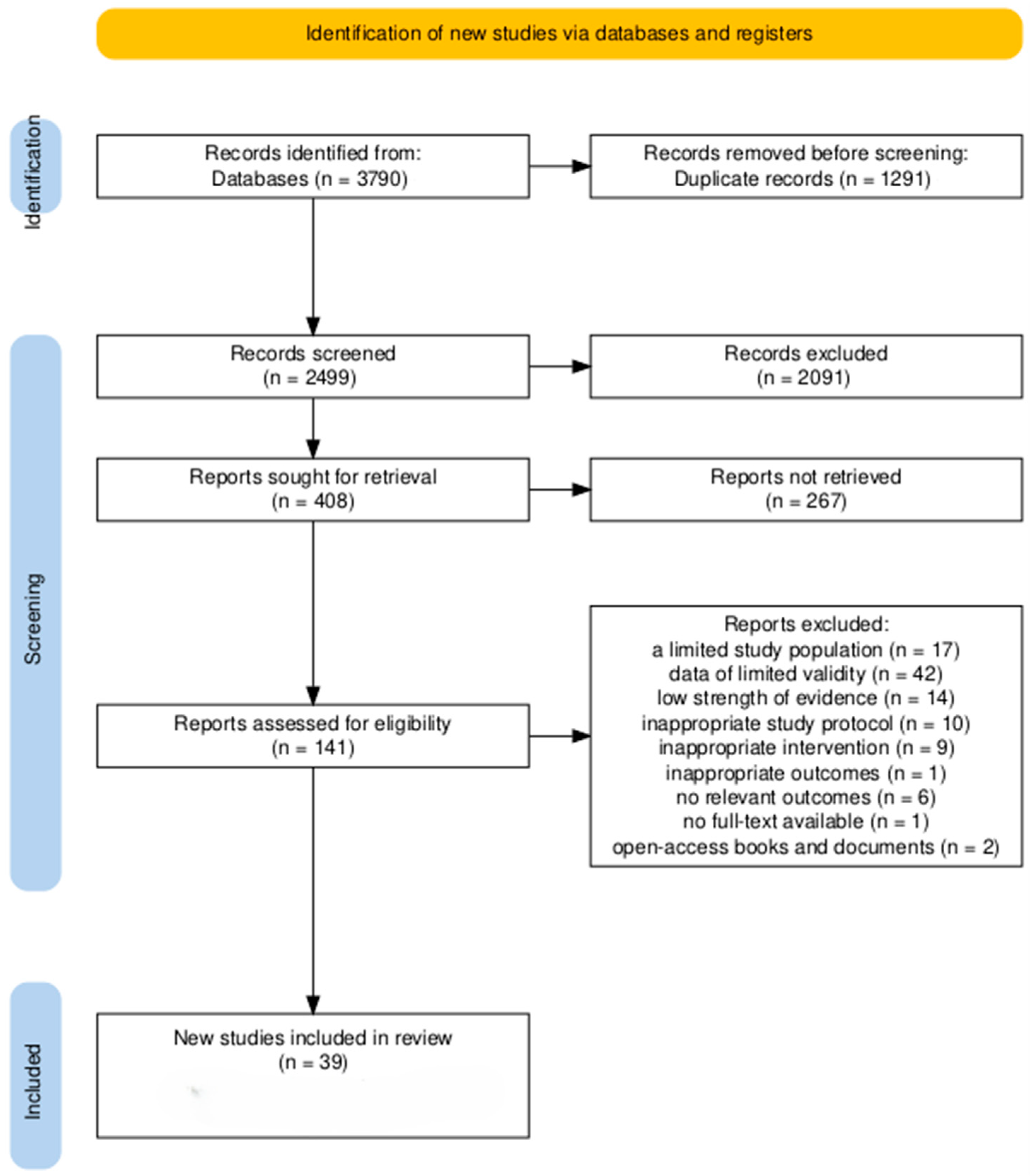

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Information on the Included Literature

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. The Role of Nurses in Delirium Diagnosis

3.3. Preventive Interventions Undertaken by Nurses

3.4. Therapeutic Interventions Undertaken by Nurses and Delirium Management

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications for Practice

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABCDEF bundle | Assess, prevent, and manage pain, Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, Choice of analgesia and sedation, Delirium: assess, prevent, and manage, Early mobility and exercise, Family engagement and empowerment |

| AS | Assessment strategy |

| 4AT | Alertness, Abbreviated Mental Test-4, Attention, Acute change or fluctuating course Test |

| CA | Cardiac arrest |

| CAM | Confusion Assessment Method |

| CAM-ICU | Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit |

| CHI | Cerebral hemodynamics improvement |

| CS | Cognitive stimulation |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition |

| Dy-Del intervention | Dynamic Delirium intervention |

| EM | Early mobilization |

| EP | Exercise program |

| FP | Family participation |

| HELP | Hospital Elder Life Program |

| ICD-10/ICD-11 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th/11th revision |

| ICDSC | Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist |

| ICUs | Intensive care units |

| KAP | Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices |

| M.O.R.E. | Music, Opening of blinds, Reorientation, Eye/Ear protocols |

| MLT | Multicomponent training |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| Nu-DESC | Nursing Delirium Screening Scale |

| PADIS guidelines | Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Guidelines |

| PC | Pain control |

| PEI | Physical environment intervention |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| SP | Sleep promotion |

| SR | Sedation reduction |

| UC | Usual care |

References

- Wójtowicz-Dacka, M.; Zając-Lamparska, L. O Świadomości. Wybrane zagadnienia. Wprow; Wydaw. UKW: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2007; p. 200. ISBN 978-83-7096-620-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Beringola, A.; Vicent, L.; Martín-Asenjo, R.; Puerto, E.; Domínguez-Pérez, L.; Maruri, R.; Moreno, G.; Vidán, M.T.; Arribas, F.; Bueno, H. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management of Delirium in the Intensive Cardiac Care Unit. Am. Heart J. 2021, 232, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prew, T.; Tahir, T.A. Delirium. Medicine 2024, 52, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, E.D.; Society, A.D. The DSM-5 Criteria, Level of Arousal and Delirium Diagnosis: Inclusiveness Is Safer. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sheikh, W.G.; Sleem, B.; Kobeissy, F.; Bizri, M. Biomarkers of Delirium and Relation to Dementia among the Elderly in the Intensive Care Unit: A Narrative Review. Biomark. Neuropsychiatry 2023, 8, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.E.; Mart, M.F.; Cunningham, C.; Shehabi, Y.; Girard, T.D.; MacLullich, A.M.J.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Ely, E.W. Delirium. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2020, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcantonio, E.R. Delirium in Hospitalized Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieges, Z.; Quinn, T.; MacKenzie, L.; Davis, D.; Muniz-Terrera, G.; MacLullich, A.M.J.; Shenkin, S.D. Association between Components of the Delirium Syndrome and Outcomes in Hospitalised Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Liu, Y.-H.; Han, Y.-Q.; Zheng, C.-Y. Risk Factors, Preventive Interventions, Overlapping Symptoms, and Clinical Measures of Delirium in Elderly Patients. World J. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher-Sánchez, S.; Satústegui-Dordá, P.J.; Ramón-Arbués, E.; Santos-Sánchez, J.A.; Aguilón-Leiva, J.J.; Pérez-Calahorra, S.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Sufrate-Sorzano, T.; Angulo-Nalda, B.; Garrote-Cámara, M.E.; et al. The Management and Prevention of Delirium in Elderly Patients Hospitalised in Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3007–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, B.; Hansen, B.R.; Hosie, A.; Budhathoki, C.; Seal, S.; Beaman, A.; Davidson, P.M. Delirium Point Prevalence Studies in Inpatient Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettel, N.; Wueest, A.S. Diagnosing Delirium in Perioperative and Intensive Care Medicine. Curr. Opin. Anesthesiol. 2023, 36, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Solimando, L.; Bolzetta, F.; Maggi, S.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Gupta, A.; Fabiano, N.; Wong, S.; Boyer, L.; Fond, G.; et al. Interventions to Prevent and Treat Delirium: An Umbrella Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 97, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeken, F.; Sánchez, A.; Rapp, M.A.; Denkinger, M.; Brefka, S.; Spank, J.; Bruns, C.; von Arnim, C.A.F.; Küster, O.C.; Conzelmann, L.O.; et al. Outcomes of a Delirium Prevention Program in Older Persons After Elective Surgery: A Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, e216370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipser, C.M.; Seiler, A.; Deuel, J.; Ernst, J.; Hildenbrand, F.; von Känel, R.; Boettger, S. Hospital-Wide Evaluation of Delirium Incidence in Adults under 65 Years of Age. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 669–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendergast, N.T.; Tiberio, P.J.; Girard, T.D. Treatment of Delirium During Critical Illness. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W.; Lange, S.; Religa, D.; Dąbrowski, S.; Friganović, A.; Oomen, B.; Krupa, S. Delirium in ICU Patients after Cardiac Arrest: A Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, T.H.; Hart, K.L.; Perlis, R.H. Characterizing and Predicting Rates of Delirium across General Hospital Settings. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2017, 46, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, F. Comparative Effectiveness of Delirium Recognition with and without a Clinical Decision Assessment System on Outcomes of Hospitalized Older Adults: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2025, 162, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Echeverría, M.d.L.; Schoo, C.; Paul, M. Delirium; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Mi, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Luo, X. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Regarding Hypoactive Delirium among ICU Nurses: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 72, 103749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, A.H.; Nymark, C.; Stenman, M.; Falk, A. Registered Nurses’ Experiences of Caring for Patients with Hypoactive Delirium after Cardiac Surgery—A Qualitative Study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 84, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.; Santos, M.; Anacleto, A.M.; Jerónimo, C.; Ferreira, Ó.; Baixinho, C.L. Nursing Intervention to Prevent and Manage Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K.; Balas, M.C.; Stollings, J.L.; McNett, M.; Girard, T.D.; Chanques, G.; Kho, M.E.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Brummel, N.E.; et al. A Focused Update to the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Anxiety, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 53, e711–e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldecoa, C.; Bettelli, G.; Bilotta, F.; Sanders, R.D.; Aceto, P.; Audisio, R.; Cherubini, A.; Cunningham, C.; Dabrowski, W.; Forookhi, A.; et al. Update of the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine Evidence-Based and Consensus-Based Guideline on Postoperative Delirium in Adult Patients. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. EJA 2024, 41, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Mȩdrzycka-Dąbrowska, W.; Tomaszek, L.; Wujtewicz, M.; Krupa, S. Nurses’ Knowledge, Barriers and Practice in the Care of Patients with Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit in Poland—A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1119526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotfis, K.; Zegan-Barańska, M.; Żukowski, M.; Kusza, K.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Ely, E.W. Multicenter Assessment of Sedation and Delirium Practices in the Intensive Care Units in Poland—Is This Common Practice in Eastern Europe? BMC Anesthesiol. 2017, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Chau, J.P.C.; Lo, S.H.S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, W. Non-Pharmacological Delirium Prevention Practices among Critical Care Nurses: A Qualitative Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morandi, A.; Piva, S.; Ely, E.W.; Myatra, S.N.; Salluh, J.I.F.; Amare, D.; Azoulay, E.; Bellelli, G.; Csomos, A.; Fan, E.; et al. Worldwide Survey of the “Assessing Pain, Both Spontaneous Awakening and Breathing Trials, Choice of Drugs, Delirium Monitoring/Management, Early Exercise/Mobility, and Family Empowerment” (ABCDEF) Bundle. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, e1111–e1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Garnacho Martins Nobre, C.F.; Dourado Marques, R.M.; Madureira Lebre Mendes, M.M.; Pontífice Sousa, P.C. The nurse’s role in preventing delirium in critically ill adult/elderly patients. Rev. Cuid. 2022, 13, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App for Producing PRISMA 2020-Compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative Research Synthesis: Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviewers Utilizing Meta-Aggregation. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto-Gussmann, E.; Höckelmann, C.; von der Lühe, V.; Schmädig, R.; Baltes, M.; Stephan, A. Patients’ Experiences of Delirium: A Systematic Review and Meta-Summary of Qualitative Research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3692–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitor, V.; Busse, T.S.; Giehl, C.; Lauer, R.; Otte, I.C.; Vollmar, H.C.; Thürmann, P.; Holle, B.; Palm, R. Educational Interventions Aimed at Improving Knowledge of Delirium among Nursing Home Staff—A Realist Review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, J.K.; Craig, L.E.; Yong, S.Q.; Siddiqi, N.; Teale, E.A.; Woodhouse, R.; Barugh, A.J.; Shepherd, A.M.; Brunton, A.; Freeman, S.C.; et al. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Preventing Delirium in Hospitalised Non-ICU Patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 7, CD013307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, K.; Sanchez, D.; Hedges, S.; Lynch, J.; Hou, Y.C.; Al Sayfe, M.; Shunker, S.-A.; Bogdanoski, T.; Hunt, L.; Alexandrou, E.; et al. A Nurse-Led Intervention to Reduce the Incidence and Duration of Delirium among Adults Admitted to Intensive Care: A Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomised Trial. Aust. Crit. Care 2023, 36, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, N.; Harrison, J.K.; Clegg, A.; A Teale, E.; Young, J.; Taylor, J.; Simpkins, S.A. Interventions for Preventing Delirium in Hospitalised Non-ICU Patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD005563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sist, L.; Pezzolati, M.; Ugenti, N.V.; Cedioli, S.; Messina, R.; Chiappinotto, S.; Rucci, P.; Palese, A. Prioritization Patterns of Nurses in the Management of a Patient With Delirium: Results of a Q-Methodology Study. Res. Nurs. Health 2025, 48, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burry, L.D.; Cheng, W.; Williamson, D.R.; Adhikari, N.K.; Egerod, I.; Kanji, S.; Martin, C.M.; Hutton, B.; Rose, L. Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Interventions to Prevent Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, F.; Penfold, R.S.; Soiza, R.L.; Von Haken, R.; Lindroth, H.; Liu, K.; Nydhal, P.; Quinn, T.J. Delirium Assessment, Management and Barriers to Effective Care across Scotland: A Secondary Analysis of Survey Data from World Delirium Awareness Day 2023. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2025, 55, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, N.Y.; Ryu, S. Effects of Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Preventing Delirium in General Ward Inpatients: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y. Non-Pharmacological Nursing Interventions for Prevention and Treatment of Delirium in Hospitalized Adult Patients: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W.; Friganovic, A.; Oomen, B.; Krupa, S. Non-Pharmacological Nursing Interventions to Prevent Delirium in ICU Patients—An Umbrella Review with Implications for Evidence-Based Practice. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannon, L.; McGaughey, J.; Verghis, R.; Clarke, M.; McAuley, D.F.; Blackwood, B. The Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Interventions in Reducing the Incidence and Duration of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rood, P.J.T.; Ramnarain, D.; Oldenbeuving, A.W.; den Oudsten, B.L.; Pouwels, S.; van Loon, L.M.; Teerenstra, S.; Pickkers, P.; de Vries, J.; van den Boogaard, M. The Impact of Non-Pharmacological Interventions on Delirium in Neurological Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Single-Center Interrupted Time Series Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herling, S.F.; Greve, I.E.; Vasilevskis, E.E.; Egerod, I.; Mortensen, C.B.; Møller, A.M.; Svenningsen, H.; Thomsen, T. Interventions for Preventing Intensive Care Unit Delirium in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD009783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehranineshat, B.; Hosseinpour, N.; Mani, A.; Rakhshan, M. The Effect of Multi-Component Interventions on the Incidence Rate, Severity, and Duration of Post Open Heart Surgery Delirium among Hospitalized Patients. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Cho, Y.S.; Lee, M.; Yun, S.; Jeong, Y.J.; Won, Y.-H.; Hong, J.; Kim, S. Effects of Nonpharmacological Interventions on Sleep Improvement and Delirium Prevention in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aust. Crit. Care 2023, 36, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, Y.; Luo, R.; Yin, N.; Wang, Y.; Jing, J.; Zhang, J. The Impact of Non-Pharmacological Sleep Interventions on Delirium Prevention and Sleep Improvement in Postoperative ICU Patients: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2025, 87, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Lee, M. Effects of Anxiety Focused Nursing Interventions on Anxiety, Cognitive Function and Delirium in Neurocritical Patients: A Non-Randomized Controlled Design. Nurs. Crit. Care 2025, 30, e70062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Tovar, L.O.; Henao Castaño, A.M. Dynamic Delirium—Nursing Intervention to Reduce Delirium in Patients Critically Ill, a Randomized Control Trial. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 83, 103691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.-X.; Cao, L.; Zhang, L.-N.; Peng, X.-B.; Zhang, L. Non-Pharmacological Interventions to Reduce the Incidence and Duration of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Crit. Care 2020, 60, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivosecchi, R.M.; Smithburger, P.L.; Svec, S.; Campbell, S.; Kane-Gill, S.L. Nonpharmacological Interventions to Prevent Delirium: An Evidence-Based Systematic Review. Crit. Care Nurse 2015, 35, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Dong, L.; Zhu, X.; Liu, J. Non-Pharmacological Interventions to Prevent and Treat Delirium in Older People: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 148, 104584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-J.; Traynor, V.; Wang, A.-Y.; Shih, C.-Y.; Tu, M.-C.; Chuang, C.-H.; Chiu, H.-Y.; Chang, H.-C.R. Comparative Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Preventing Delirium in Critically Ill Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 131, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Tan, S.; Guan, Y.; Luo, X. Psychological Stress and Associated Factors in Caring for Patients with Delirium among Intensive Care Unit Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Aust. Crit. Care 2023, 36, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, M.L.; Henriques, A.; Melo, G.; Henriques, H.R. The Effectiveness of Family Participation Interventions for the Prevention of Delirium in Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2025, 89, 103976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.; Thorhauge, K.A.L.; Petri, C.L.; Madsen, M.T.; Burcharth, J.F.H. Preventative Interventions for Postoperative Delirium after Intraabdominal Surgery—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Am. J. Surg. 2025, 243, 116245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y. Effectiveness of Nurse-led Non-pharmacological Interventions on Outcomes of Delirium in Adults: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2024, 21, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, J.; Duan, J. Effects of Sensory-Based Interventions on Delirium Prevention in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2025, 31, e13321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelin, M.; Sert, H. The Effect of Nursing Care Provided to Coronary Intensive Care Patients According to Their Circadian Rhythms on Sleep Quality, Pain, Anxiety, and Delirium: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, Y.; Ohno, Y.; Toyoshima, M.; Ueno, T. Effects of Non-Pharmacologic Prevention on Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Network Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 28, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yuan, W. Perioperative Multicomponent Interdisciplinary Program Reduces Delirium Incidence in Elderly Patients With Hip Fracture. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2022, 28, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unal, N.; Guvenc, G.; Naharci, M. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Delirium Prevention Care Protocol for the Patients with Hip Fracture: A Randomised Controlled Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 1082–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, C.; Cirbus, J.; Han, J. Emergency Department Interventions and Their Effect on Delirium’s Natural Course: The Folly May Be in the Foley. J. Emergencies Trauma Shock 2019, 12, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.G.; Falavigna, M.; da Silva, D.B.; Sganzerla, D.; Santos, M.M.S.; Kochhann, R.; de Moura, R.M.; Eugênio, C.S.; Haack, T.d.S.R.; Barbosa, M.G.; et al. Effect of Flexible Family Visitation on Delirium Among Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: The ICU Visits Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 322, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustino, T.N.; Suzart, N.A.; Rabelo, R.N.D.S.; Santos, J.L.; Batista, G.S.; Freitas, Y.S.d.; Saback, D.A.; Sales, N.M.M.D.; Brandao Barreto, B.; Gusmao-Flores, D. Effectiveness of Combined Non-Pharmacological Interventions in the Prevention of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Crit. Care 2022, 68, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Jung, Y.-J.; Choi, N.-J.; Hong, S.-K. The Effects of Environmental Interventions for Delirium in Critically Ill Surgical Patients. Acute Crit. Care 2023, 38, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.; Ling, N.; Ho, V.W.T.; Vidhya, N.; Chen, M.Z.; Wong, B.L.L.; Ng, S.E.; Murphy, D.; Merchant, R.A. Delirium Is Significantly Associated with Hospital Frailty Risk Score Derived from Administrative Data. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Ye, C.; Ma, D.; Wang, E. Emergence Delirium and Postoperative Delirium Associated with High Plasma NfL and GFAP: An Observational Study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, T.E.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Jung, E.; Swanson, A.; Ing, C.; Garcia, P.S.; Whittington, R.A.; Moitra, V. Association of Delirium With Long-Term Cognitive Decline: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, A.; Kirwan, M.; Bannon, L. Nurses’ Usage of Validated Tools to Assess for Delirium in General Acute Care Settings: A Scoping Review Protocol. HRB Open Res. 2025, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Huraizi, A.R.; Al-Maqbali, J.S.; Al Farsi, R.S.; Al Zeedy, K.; Al-Saadi, T.; Al-Hamadani, N.; Al Alawi, A.M. Delirium and Its Association with Short- and Long-Term Health Outcomes in Medically Admitted Patients: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetz, A.; Weiss, B.; Boettcher, S.; Burmeister, J.; Wernecke, K.-D.; Spies, C. Routine Delirium Monitoring Is Independently Associated with a Reduction of Hospital Mortality in Critically Ill Surgical Patients: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. J. Crit. Care 2016, 35, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C. Confusion and Delirium in the Acute Setting. Medicine 2017, 45, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollings, J.L.; Kotfis, K.; Chanques, G.; Pun, B.T.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Ely, E.W. Delirium in Critical Illness: Clinical Manifestations, Outcomes, and Management. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nydahl, P.; Liu, K.; Bellelli, G.; Benbenishty, J.; van den Boogaard, M.; Caplan, G.; Chung, C.R.; Elhadi, M.; Gurjar, M.; Heras-La Calle, G.; et al. A World-Wide Study on Delirium Assessments and Presence of Protocols. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Coleman, M.; Terry, D. Nurses’ Experience of Caring for Patients with Delirium: Systematic Review and Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fordyce, C.B.; Katz, J.N.; Alviar, C.L.; Arslanian-Engoren, C.; Bohula, E.A.; Geller, B.J.; Hollenberg, S.M.; Jentzer, J.C.; Sims, D.B.; Washam, J.B.; et al. Prevention of Complications in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142, e379–e406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional para la Excelencia en la Salud y la Atención (NICE). Delirium: Prevention, Diagnosis and Management in Hospital and Long-Term Care. NICE Guidelines; Instituto Nacional para la Excelencia en la Salud y la Atención (NICE): Ra’Anana, Israel, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, Z.; Kaya, M.; Aksoy, M.; Karaman Özlü, Z. Investigation of the Factors Affecting Delirium Evaluation by Intensive Care Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewulak, K.D.; Stelfox, H.T.; Leigh, J.P.; Ely, E.W.; Fiest, K.M. Incidence and Prevalence of Delirium Subtypes in an Adult ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewulak, K.D.; Stelfox, H.T.; Ely, E.W.; Fiest, K.M. Risk Factors and Outcomes among Delirium Subtypes in Adult ICUs: A Systematic Review. J. Crit. Care 2020, 56, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, C.J.; Marra, A.; Han, J.H.; Patel, M.B.; Brummel, N.E.; Thompson, J.L.; Jackson, J.C.; Chandrasekhar, R.; Ely, E.W.; Pandharipande, P.P.; et al. Association of Hypoactive and Hyperactive Delirium With Cognitive Function After Critical Illness. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e480–e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, J.; Norcott, A.; Benn, L.; Shah, N.; McKinney, A.; Min, L.; Vlisides, P.E. Barriers to Delirium Screening and Management during Hospital Admission: A Qualitative Analysis of Inpatient Nursing Perspectives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.W.; Skrobik, Y.; Gélinas, C.; Needham, D.M.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Watson, P.L.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; Rochwerg, B.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, e825–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, G.U.; Towell-Barnard, A.; McLean, C.; Ewens, B. The Development of a Family-Led Novel Intervention for Delirium Prevention and Management in the Adult Intensive Care Unit: A Co-Design Qualitative Study. Aust. Crit. Care Off. J. Confed. Aust. Crit. Care Nurses 2025, 38, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosted, E.E.; Prokofieva, T.V.; Sanders, S.C.; Schultz, M. Serious Consequences of Malnutrition and Delirium in Frail Older Patients. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 37, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, A.; Inzitari, M.; Udina, C.; Gual, N.; Mota, M.; Tassistro, E.; Andreano, A.; Cherubini, A.; Gentile, S.; Mossello, E. Visual and Hearing Impairment Are Associated With Delirium in Hospitalized Patients: Results of a Multisite Prevalence Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1162–1167.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, D.; Yeo, M.S.; Yoo, G.E.; Kim, S.J.; Na, S. Effects of Patient-Directed Interactive Music Therapy on Sleep Quality in Postoperative Elderly Patients: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2020, 12, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slooter, A.J.C. Nonpharmacological Interventions in Delirium: The Law of the Handicap of a Head Start. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rood, P.J.T.; Zegers, M.; Ramnarain, D.; Koopmans, M.; Klarenbeek, T.; Ewalds, E.; van der Steen, M.S.; Oldenbeuving, A.W.; Kuiper, M.A.; Teerenstra, S.; et al. The Impact of Nursing Delirium Preventive Interventions in the ICU: A Multicenter Cluster-Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hshieh, T.T.; Yue, J.; Oh, E.; Puelle, M.; Dowal, S.; Travison, T.; Inouye, S.K. Effectiveness of Multicomponent Nonpharmacological Delirium Interventions: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Free Full Text | By Titles | By Abstracts | Included | Duplicates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | 1356 | 674 | 172 | 40 | 20 | |

| Scopus | 1310 | 686 | 118 | 46 | 12 | |

| CINAHL/EBSCO | 1125 | 542 | 118 | 55 | 8 | |

| Total: | 3791 | 1902 | 408 | 141 | 40 | 1291 |

| Number | Reference | Setting/Population/Country | Publication Type | Scope of the Study | Main Conclusion | The Main Conclusions Regarding the Role of Nurses | Study Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | [36] | Patients hospitalised out of ICU | Systematic review (22 studies included) | Nonpharmacological interventions | Complex, nonpharmacological interventions have little or no effect on patient mortality in the hospital. However, they can shorten the duration of delirium episodes and reduce the length of hospitalisation. | Nurses play a role in implementing multicomponent interventions to prevent delirium, particularly through protocols such as reorientation, cognitive stimulation, and sleep hygiene. They are involved in assessing and addressing delirium risk factors, indicating a proactive role in prevention. | Multicomponent nonpharmacological interventions show limited effectiveness. They can reduce delirium incidence and duration, but do not significantly impact patient mortality. Study interpretations are limited by: lack of blinding (risk of bias), scarce data on patients with dementia, limited evidence for single-component interventions, inconsistent frailty assessment and subgroup reporting, insufficient attention to cognitive outcomes and dementia progression. |

| 2. | [37] | ICU patients (N = 2566)/Australia | Original study | Multicomponent interventions carried out by nurses | Overall, the nursing-led intervention did not produce a meaningful decrease in either the occurrence or the duration of delirium. | Nurses play a role in delivering and promoting the delirium prevention protocol. However, despite their involvement, the intervention did not lead to a statistically significant reduction in either the incidence or the duration of delirium and, thus, failed to achieve the expected outcomes. | Owing to the lower-than-anticipated baseline incidence of delirium (14%), the achieved sample size lacked sufficient statistical power to detect the observed effect size. |

| 3. | [12] | Perioperative and ICU patients | Review (narrative review) | Diagnostic approaches to delirium | Timely diagnosis and treatment of delirium are critical to preventing serious adverse outcomes such as death and institutionalisation. More than 30 tools are available for screening and diagnosing delirium, but they vary in sensitivity, specificity, and time to diagnosis, which complicates their selection and comparison. | Nurses, due to their daily patient contact, can detect early signs using reliable screening tools (e.g., CAM-ICU, 4AT). Timely diagnosis prevents complications, and regular use of screening tools is essential for effective nursing care and improved patient outcomes. | An excessive number (more than 30) of diagnostic tools complicates selection and comparison in studies, thereby complicating the process of standardisation and comparison of diagnostic methods. Healthcare professionals may not be sufficiently familiar with the various assessments of delirium, indicating a gap in education and training. |

| 4. | [38] | Patients hospitalized out of ICU | Systematic review and meta-analysis (39 studies included) | Preventive, multicomponent interventions | Multicomponent interventions significantly reduce the incidence of delirium in hospitalised patients compared to usual care. The study shows that monitoring the depth of anaesthesia using Bispectral Index-guided anaesthesia reduces the incidence of postoperative delirium compared to anaesthesia without such monitoring. | Nurses play a central role in multidisciplinary teams by participating in educational programs, implementing protocols that address specific risk factors, and delivering specialised interventions such as medication management and mobilisation. | Evidence for delirium prevention outside the ICU is limited, except for multicomponent interventions. Many studies had small samples, high heterogeneity, and lacked data on key subgroups (e.g., patients with dementia). Most did not exclude patients with preexisting delirium, affecting accuracy. Outcomes like delirium duration, severity, mortality, functional status, adverse events, quality of life, caregiver or staff burden, and costs were rarely assessed. |

| 5. | [14] | Elderly patients after elective surgery (N = 1470)/Germany | Original study | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological multimodal intervention is effective in reducing the risk of delirium in elderly patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. | Nurses played a role in the delirium prevention by participating in training on delirium detection and prevention, implementing intervention modules, evaluating outcomes, mentoring volunteers, and ensuring program feasibility and fidelity. | The intervention did not influence the incidence of delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Its feasibility and effectiveness should be further evaluated in smaller, nonacademic, and rural hospitals. Patient readmissions after discharge were not reported, and analyses of ICU stays must be interpreted with caution due to variability in institutional protocols. |

| 6. | [39] | Nurses–managing patients with delirium | Systematic review (12 included studies) | Analysis of nurses’ priorities | Nurses generally prioritise patient safety, communication, and monitoring, but individual approaches vary: some tailor interventions to patient needs, others focus on prevention. These differences can delay active delirium treatment and highlight the need for consistent communication, cognitive reorientation, and harmonised decision-making to improve care quality. | Nurses prioritise interventions in delirium management, with a particular focus on safety and communication. Priority patterns vary across levels, reflecting different approaches to care. | The Q-sample was derived from the literature and may have overemphasised certain interventions. The systematic review excluded primary studies included within other systematic reviews. The scenario used to prompt reasoning may have been overly limited, and online data collection could have restricted in-depth engagement. Nurses’ knowledge and prior experience with delirium management were not assessed. Additionally, data collection took place during the pandemic, which may have influenced prioritisation. |

| 7. | [40] | Patients in critical condition | Systematic review and meta-analysis (38 included studies) | Pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions | Nonpharmacological interventions have not demonstrated a significant impact on delirium prevention or ICU length of stay. | Nurses play a role in preventing delirium in critically ill patients by monitoring sedation, applying sedation protocols, observing patients, and documenting symptoms. Their cooperation in implementing evidence-based pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions is important. | Many of the included studies did not use blinding, which increases the risk of bias. Data on patients with dementia were limited, and the effectiveness of single-component interventions was not sufficiently documented. Some studies did not exclude patients with existing delirium, which may have affected the assessment of the effectiveness of the interventions. In addition, cognitive outcomes and dementia progression were rarely assessed, and the implementation of multicomponent interventions requires further study. |

| 8. | [41] | Patients from various hospital wards (N = 3257)/United Kingdom | Secondary analysis of survey data | Identifying barriers in the assessment and care of patients with delirium | Delirium management includes nonpharmacological interventions like pain control, hydration, and family visits. Insufficient staffing and training are major barriers to effective care. | Nurses are responsible for assessing delirium and participate in the implementation of nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions. The barriers reported include staff shortages and lack of time for staff education and training. | All survey data was provided by clinicians participating in World Delirium Awareness Day 2023, without verification of the data provided. |

| 9. | [42] | General wards patients | Systematic review and meta-analysis (17 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | Multicomponent nonpharmacological interventions are effective in reducing the incidence of delirium in general wards. These interventions are effective in both medical and surgical wards. | Nurses implement nonpharmacological interventions to prevent delirium. | Many studies did not report the frequency or duration of nonpharmacological interventions, which contributed to variability in intervention components across studies and made it difficult to standardise multicomponent interventions. This variability, along with the limited number of studies on surgical patients, prevented meta-analysis of single-component interventions. |

| 10. | [43] | Adults admitted to hospital | Systematic review and meta-analysis (9 included studies) | Intervention carried out by nurses | Nonpharmacological nursing interventions for delirium prevention and treatment include multi-component interventions, multidisciplinary care, multimedia education, listening to music, and others. These interventions are effective in preventing delirium, especially in general wards and through multicomponent programs. Interventions are commonly used in surgical wards and are often repeated, with cognitive interventions being a significant component. | Nurses are key in preventing and managing delirium through nonpharmacological interventions, leading teams, implementing strategies independently, supporting families, and contributing to research on improving care. | The interventions were highly heterogeneous due to differences in activities, providers, and timing, and the literature search was insufficient. Only four of the nine studies were assessed as having a low overall risk of bias. Variability in delirium screening scales further complicated comparisons, and the analysis of nonpharmacological interventions delivered by nurses was limited. |

| 11. | [44] | Adults admitted to the ICU | Systematic review (14 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | Nonpharmacological nursing interventions are effective in preventing and reducing the duration of delirium in ICU patients. Multicomponent interventions are the most promising strategy for preventing delirium. Family involvement and cognitive exercises are beneficial in reducing the incidence and duration of delirium. | Nurses play a role in implementing nonpharmacological interventions to prevent delirium in ICU patients. They should involve family members in the prevention process, conduct delirium assessments, and work as part of a multidisciplinary team to minimise risk and prevent delirium. | While multifactorial interventions appear effective, the most beneficial combinations of specific interventions remain unclear, highlighting the need for research that focuses on integrating single interventions into multifactorial approaches. |

| 12. | [23] | Patients in critical condition | Scoping review (15 included studies) | Intervention carried out by nurses | Nonpharmacological interventions-such as sleep promotion, reorientation, cognitive stimulation, early mobilisation, comfort measures, and anxiety reduction-are essential for delirium prevention and management. Early recognition and timely intervention improve outcomes and quality of life. | Nurses are central in assessing, preventing, and treating delirium through both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. In the ICU, they monitor patients, collaborate with medical teams, administer medications, implement multicomponent strategies, and follow guidelines like the ABCDEF bundle, requiring proper training to ensure effective care. | Restrictions in language and free access to full texts may have led to the exclusion of relevant articles. The included studies were heterogeneous and lacked assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias, limiting the strength of clinical recommendations. |

| 13. | [45] | Patients in critical condition | Systematic review and meta-analysis (15 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | Current evidence does not support the effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions (early mobilisation, cognitive stimulation, sleep promotion, environmental modifications) in reducing the incidence and duration of delirium in critically ill patients. | Nurses play a key role in implementing nonpharmacological interventions by identifying early signs of delirium, and their active involvement and education are essential to the success of these interventions. | The overall evidence quality was low due to high risk of bias, small sample sizes, and heterogeneous interventions, populations, and outcomes. Delirium reporting was inconsistent, many patients were unassessable, and high-risk populations were overrepresented. |

| 14. | [46] | Neurological ICU patients (N = 120)/Netherlands | Original paper | Nonpharmacological interventions | A multicomponent nonpharmacological nursing intervention program did not significantly change the number of delirium-free and noncomatose days after 28 days in patients with neurological ICU admission. The intervention had no significant effect on secondary outcomes such as incidence and duration of delirium. | Nurses play a role in implementing a multicomponent nonpharmacological intervention program aimed at reducing delirium in patients in the neurological ICU. They are responsible for optimising vision, hearing, orientation, sleep, cognitive function, and mobility, the impairment of which is a risk factor, and were able to tailor the program to the individual needs of patients. However, the program did not significantly improve the number of delirium-free and coma-free days after 28 days. | The overall quality of evidence was low due to a high risk of bias. Heterogeneity in interventions, populations, and outcomes prevented data pooling, and some studies had small sample sizes. Inconsistent reporting of delirium incidence and duration, combined with the inability to assess patients in drug- or trauma-induced coma, limited generalisability. The focus on high-risk patients restricted applicability to lower-risk populations, and delirium assessment using CAM-ICU rather than DSM-5 criteria may have underestimated prevalence. |

| 15. | [11] | Adults admitted to hospital | Systematic review and meta-analysis (9 included studies) | Research on the prevalence of delirium | The relationship between immobility, sleep deprivation, and delirium are important issues to consider, especially in intensive care units. | Recommendations for caregivers, including nurses, regarding early diagnosis and treatment of delirium have been confirmed. Nurses should have appropriate tools to monitor delirium in order to recognise it in a timely manner, and intervention recommendations should be widely used. Delirium can be superimposed on dementia. | The studies were heterogeneous in populations and assessment tools, highlighting the need for standardised screening in hospitals. Only English-language and hospital-based studies were included, limiting generalisability. Potential publication bias and methodological diversity restrict the strength of recommendations for guidelines and care models. |

| 16. | [47] | Adults admitted to the ICU | Cochrane review (12 included studies) | Interventions to prevent delirium in the ICU | There is probably little or no difference between haloperidol and placebo in preventing ICU delirium, but further studies are needed to increase confidence in these results. There is insufficient evidence to determine the effect of physical and cognitive interventions on delirium. The effect of other pharmacological interventions, sedation, environment, and nursing care on delirium is unclear and requires further research. | There is potential for nursing interventions to reduce the incidence of delirium in the intensive care unit by targeting predisposing and triggering factors, but more research is needed to confirm their effectiveness. | The quality of evidence is low due to small sample sizes and lack of blinding, highlighting the need for further research to clarify the effectiveness of these interventions. |

| 17. | [48] | Patients after open heart surgery (N = 48)/Iran | Original paper | Multicomponent interventions: preoperative patient education, nursing education, environmental interventions | The intervention did not have a significant impact on preventing or reducing delirium, as differences in incidence, severity, and duration compared to the control group were not statistically significant. | Patient education and nurse training as part of multicomponent interventions did not lead to a statistically significant reduction in the incidence, severity, or duration of delirium following open-heart surgery. | Assessing delirium symptoms only three times a day may overlook fluctuations in severity, which may affect the accuracy of the results. |

| 18. | [49] | Patients in critical condition, ICU patients | Systematic review (118 included studies) and meta-analysis (100 included studies) | Sleep-related interventions | Nonpharmacological interventions significantly improved subjective sleep quality and reduced the incidence and duration of delirium in ICU patients. Specific interventions such as aromatherapy, music, and massage improved sleep, while exercise, family involvement, and others reduced delirium. Light/noise blocking was effective in both improving sleep and preventing delirium. | Nurses should use nonpharmacological interventions that promote environmental compatibility in their clinical practice to improve sleep and prevent delirium in ICU patients. | Excluding studies not published in English or lacking full-text availability is a limitation, as it may have led to the omission of relevant research. |

| 19. | [50] | Postoperative ICU patients | Systematic review and meta-analysis (17 included studies) | Sleep-related interventions | The most effective way to prevent delirium in postoperative patients in intensive care units is through multicomponent nonpharmacological interventions that improve sleep quality by maintaining the circadian sleep/wake rhythm and alleviating stress. | Nurses should pay attention to the patient’s circadian rhythm and stress levels and implement targeted interventions into routine care. The implementation of multicomponent interventions into nurses’ work may generate an increase in workload, which suggests a significant role in the management of these interventions. | Several studies show a risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision, and heterogeneity, leading to very low quality of evidence. |

| 20. | [51] | Neurocritical patients, ICU patients (N = 60)/South Korea | Original paper | Interventions focused on anxiety and cognitive function | Nursing intervention focused on anxiety significantly reduced anxiety levels in the experimental group compared to the control group. The intervention improved cognitive function in the experimental group. | Nurses play a vital role in implementing comprehensive nursing interventions to address psychological and cognitive needs, reduce anxiety, improve cognitive function, and reduce the risk of delirium in patients in neurocritical care units. Nurses’ training is essential because it is critical to the effective implementation and improvement of patient outcomes. | Participants were recruited from a single ICU, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The study assessed only short-term outcomes, and long-term effects on anxiety, cognitive function, and delirium remain unknown. The nonrandomized, controlled design may have introduced selection and measurement bias. Additionally, interventions were implemented under controlled conditions, which may not fully represent real-world practice. |

| 21. | [52] | Patients in critical condition, ICU patients (N = 213)/Colombia | Original paper | Intervention carried out by nurses | The Dy-Del intervention, a nonpharmacological approach involving family engagement, appears effective in reducing both the incidence and duration of delirium, as well as pain intensity, in adult ICU patients. | Nurses play a key role in implementing Dy-Del interventions, which do not involve administering medication but focus on meeting physiological, psychological, spiritual, and social needs. Nurses are crucial in reducing the incidence and duration of delirium and can provide humane care through the use of Dy-Del. | The study did not assess anxiety and stress levels before and after implementing the protocol. Contamination bias may have occurred, as some ICU staff applied elements of the Dy-Del intervention to control group patients. Additionally, the impact of additional workload and adherence to the intervention was not measured. |

| 22. | [53] | Patients in critical condition | Systematic review and meta-analysis (26 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | Family involvement is one of the most effective interventions for reducing the incidence of delirium in critically ill patients. Multicomponent strategies are generally optimal intervention techniques for preventing delirium and reducing the length of stay in the ICU. | The various interventions studied-physical environment intervention (PEI), sedation reduction (SR), family participation (FP), exercise program (EP), improvement of cerebral hemodynamics (CHI), multicomponent training (MLT), and usual care (UC)-highlight the critical role of nurses in engaging families in patient care to help reduce the incidence of delirium. | The study lacks information on the frequency, duration, and number of interventions. Although multicomponent strategies are considered optimal, specific details on how interventions were combined, their frequency, or duration are not provided. Similarly, no detailed information is available for other interventions, including PEI, SR, EP, and CHI. |

| 23. | [54] | Adults admitted to the ICU | Systematic review (17 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | The implementation of a nonpharmacological protocol effectively prevents delirium by controlling risk factors, significantly reducing both its incidence and duration. | Nurse education was an integral part of the protocol, enabling nurses to actively implement nonpharmacological interventions. They play a central role in the M.O.R.E. interventions-Music, Opening of blinds, Reorientation and cognitive stimulation, and Eye/Ear protocols-which led to a significant reduction in delirium in the ICU and improved patients’ quality of life. This highlights the critical role of nurses in successfully delivering nonpharmacological strategies. | The review did not provide a detailed assessment of study bias. Heterogeneity in patient populations, interventions, and outcome measures, as well as the use of different delirium assessment tools, limits comparability and generalisability of the findings. |

| 24. | [55] | Elderly patients | Systematic review and meta-analysis (24 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | Multicomponent interventions effectively prevent delirium. Single-component interventions may help prevent delirium but have limited impact on its duration and severity. Overall, nonpharmacological treatments have limited effectiveness in delirium management. | The use of nonpharmacological interventions to help reduce the incidence of delirium. | The variability in results and quality across systematic reviews makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. |

| 25. | [21] | ICU nurses (N = 2835)/China | Original paper | KAP protocol (knowledge, attitudes, practices) concerning hypoactive delirium | A significant percentage of ICU nurses have a positive attitude and adequate practice toward hypoactive delirium, but their level of knowledge is very low. Factors such as age, years of working in the ICU, education, and training in hypoactive delirium are significantly associated with KAP status. Hypoactive delirium is often ignored by nurses and there is no specific nursing procedure that requires improvement in training and standard procedures. | Nurses have poor knowledge of hypoactive delirium. Enhanced training is essential to improve knowledge, attitudes, and practice. | Hospitals were not randomly selected but were chosen through convenience sampling, which may introduce selection bias. |

| 26. | [13] | Patients from different wards | Umbrella review (59 included studies) | Preventive and therapeutic interventions | Delirium prevention and treatment are not well understood, with limited high-certainty evidence. Dexmedetomidine is effective for surgical patients, while nonpharmacological strategies—light sedation, comprehensive geriatric assessment, and multi-component interventions—show benefits, especially in older adults. | The use of nonpharmacological interventions in ICUs and other medical units seems to be confirmed; nurses should use standardised protocols containing multi-component interventions addressing six risk factors: cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual impairment, hearing impairment, and dehydration. Nonpharmacological interventions may be preferred as first-line treatment. | The review included only meta-analyses of RCTs in hospitalised patients, with most evidence derived from surgical populations and no consideration of delirium subtypes, limiting generalisability. |

| 27. | [56] | Patients in critical condition | Systematic review and meta-analysis (29 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | The most effective nonpharmacological ICU interventions are multicomponent measures-especially early mobilisation and family involvement-which reduce delirium incidence and duration, supporting evidence-based care optimisation for critically ill patients. | Nurses providing care to patients in the ICU can effectively influence the incidence and duration of delirium by implementing several nonpharmacological measures. | The included studies were heterogeneous and of low to moderate quality. |

| 28. | [57] | ICU nurses (N = 355)/China | Original paper | Assessment of psychological stress in ICU nurses caring for delirium patients | Intensive care nurses experience moderate stress caused by caring for patients with delirium. Factors that increase stress include: current experiences related to caring for delirious patients, less knowledge, low satisfaction with support (e.g., organisational), lower psychological resilience of nurses, and low professional self-esteem. There is a need to support nurses who influence these factors. | Caring for patients with delirium can be challenging and stressful for nurses, who often experience moderate levels of work-related stress. Psychological assessment and support are important to safeguard nurses’ mental health and enhance the quality of care. Nurse managers and researchers should prioritise the well-being of ICU nurses by offering targeted support, increasing delirium-related knowledge, and strengthening resilience and coping skills. | The cross-sectional design limits the ability to determine causal relationships. Conducted in only three hospitals in China, and the sample may not be representative of all nurses. |

| 29. | [18] | Patients from different wards (N = 831,348)/United States | Original paper | Characteristics and prediction of delirium frequency | Delirium incidence varies by diagnosis and ward type, with maternity wards showing the lowest rates. Diagnosis and hospitalisation location are stronger predictors than age, highlighting the need for targeted prevention and treatment strategies. | Nurses should take into account the increased risk of delirium in patients hospitalised in high-risk wards. | The present study reported experience at two centres, both of which were tertiary referral centers in the same geographic area. The sample may not be representative of all nurses. |

| 30. | [58] | Family of patients admitted to the ICU | Systematic review (14 included studies) | Family participatory interventions | Single-component interventions, such as familiar voice messages and flexible visits, have shown beneficial effects in reducing delirium. Multicomponent interventions, including family visits with professional support programs and sensory stimulation, have also shown positive effects in reducing the incidence and duration of delirium. | Although it does not directly discuss the role of nurses, those who are closest to the patient can encourage and engage the family during the provision of care. | The results were highly heterogeneous, preventing meaningful data synthesis and limiting the ability to draw definitive conclusions. |

| 31. | [59] | Postoperative patients (abdomen) | Systematic review and meta-analysis (16 included studies) | Interventions to prevent delirium after intra-abdominal surgery: (I) bundle care: multicomponent, coordinated preventive and nursing programs; (II) anaesthesia interventions: variations in anaesthesia techniques and intraoperative oxygen management; and (III) pharmacological interventions: medication administration aimed at delirium prevention. | Multimodal interventions can reduce postoperative delirium by 49%, with risk influenced by surgical technique and anaesthesia type. Clear communication, family involvement, standardised protocols, and a multidisciplinary approach-including early risk identification and combined nonpharmacological and pharmacological strategies-are key to effective prevention and treatment. | Nurses are part of a multidisciplinary team that works together to care for patients and can encourage families to cooperate. | The authors conducted an analysis of the heterogeneity of results, pointing to significant differences between studies. A subgroup analysis indicated a greater effect of the intervention in smaller studies, which were characterised by a higher risk of research errors. It should be noted that the authors did not perform a formal assessment of the risk of research errors in individual studies, which may limit the interpretation of the results. |

| 32. | [60] | Patients from different wards | Meta-analysis (32 included studies) | Intervention carried out by nurses | Multicomponent nonpharmacological interventions effectively reduce the incidence of delirium in hospitalised patients and mortality, but do not significantly affect its duration, severity, or length of hospitalisation. | Nurses effectively improve treatment outcomes by using nonpharmacological multicomponent interventions, but this can increase the workload of staff. | The included studies were heterogeneous in interventions, patient populations, and outcomes, limiting data synthesis. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2.0, but specific biases were not detailed. Publication bias was not explicitly addressed, potentially overestimating intervention effectiveness. |

| 33. | [10] | Elderly patients in the ICU | Systematic review (14 included studies) | Delirium management and prevention | Pharmacological interventions have been identified as viable pharmacological options for reducing the incidence of delirium. Bright light therapy to improve circadian rhythm and sleep/wake cycles, and the combination of epidural and general anaesthesia was effective, as were nonpharmacological and mixed interventions. | As part of nonpharmacological interventions, nurses can use nursing programs that focus on optimising modifiable risk factors and using therapies such as bright light therapy. | The authors point to significant heterogeneity in the included studies, including differences in diagnostic tools, populations, and age criteria, which makes it difficult to compare results. In addition, the number of studies on nonpharmacological interventions is limited, and their samples are small, which reduces the strength of the evidence. Another significant limitation is the lack of analysis of the effectiveness of interventions in relation to different types of delirium. |

| 34. | [61] | Patients in critical condition | Systematic review and meta-analysis (14 included studies) | Sensory interventions | Sensory interventions, particularly auditory stimulation, can help reduce the risk of delirium in critically ill ICU patients, although overall sensory-based strategies show limited effectiveness in prevention. | When choosing sensory interventions, nurses should prefer auditory stimulation. | The study did not provide a detailed assessment of methodological limitations or risk of bias. Potential limitations include the lack of randomisation and a control group, absence of blinding, single-center design limiting generalisability, no evaluation of long-term outcomes (e.g., cognitive function or quality of life), and unaddressed potential for publication bias. |

| 35. | [62] | Coronary ICU patients (N = 44)/Turkey | Original paper | Nurse-led circadian rhythm–based care: scheduling care to minimise nighttime disturbances, noise control, and use of earplugs to improve sleep, reduce pain and anxiety, and prevent delirium. | Nursing care should be adapted to the patient’s natural circadian rhythm, provided at the right time, and focused on improving sleep quality, as sleep problems can cause pain, anxiety, and delirium. | Nurses caring for patients in accordance with the sleep–wake cycle and assessing the need for intervention effectively improve sleep quality, reducing pain, anxiety, and delirium in patients receiving intensive cardiac care. | Single-center study with a small sample size. Potential confounding factors, such as medications and comorbidities, were not controlled. Reliance on self-reported measures of sleep quality and anxiety may introduce measurement bias. |

| 36. | [63] | Patients in critical condition | Meta-analysis (11 included studies) | Nonpharmacological interventions | Multicomponent interventions significantly reduced the incidence of delirium in critically ill patients. These include: sleep promotion (SP): noise and light control, minimisation of night care; cognitive stimulation (CS): orientation of patients to date, time, and place; hearing and visual acuity support; music, word games, crossword puzzles, and board games; early mobilisation (EM); pain control (PC); and assessment. | Nurses are an integral part of the intensive care team and play a key role in the multidisciplinary team implementing multicomponent interventions to prevent delirium, particularly in interventions requiring specialist knowledge and skills. | Studies included small sample sizes, showed variable quality in reviews and meta-analyses, lacked blinding and randomisation in some cases, raised risk of bias concerns, and did not provide direct head-to-head comparisons. |

| 37. | [64] | Elderly patients with femoral neck fractures (N = 174)/China | Original paper | A multi-component interdisciplinary program | A nurse-led, multicomponent interdisciplinary program can effectively reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium and postoperative hypoxia in elderly patients with femoral neck fractures. However, it does not appear to significantly affect the severity or duration of delirium, nor the overall length of hospital stay. | An interdisciplinary, multi-component perioperative program led by nurses is feasible and effective in reducing the incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly patients with hip fractures, indicating the important role of nurses in preventing delirium. | The study did not provide a detailed assessment of methodological limitations or risk of bias. Potential limitations include the lack of randomisation and a control group, absence of blinding, single-center design limiting generalisability, no evaluation of long-term outcomes (e.g., cognitive function or quality of life), and unaddressed potential for publication bias. |

| 38. | [65] | Patients with femoral neck fractures (N = 41)/Turkey | Original paper | Delirium prevention protocol | Implementing a multicomponent care protocol- including vital signs monitoring, oxygen support for saturation below 90%, nutrition and hydration assessment, and patient orientation-can improve patient outcomes and support delirium prevention. | Nurses play a central role in preventing delirium by identifying risk factors and managing at-risk patients according to established protocols. Their early recognition and holistic care are essential for timely intervention. Training in nonpharmacological strategies to improve sleep and manage delirium risk factors, combined with collaboration with geriatric units, supports a comprehensive approach to patient care. | Single-researcher study with patient assessments limited to twice daily. Although the geriatrician was blinded to group assignments, the evaluation process may still have caused bias. The protocol is specific to older patients with hip fractures, limiting generalisability to other age groups or conditions. |

| 39. | [66] | Emergency department patients (N = 3383)/United States | Original paper | Practical interventions. Evaluation of factors affecting delirium duration. | Bladder catheterisation in elderly patients in the emergency department is associated with a longer duration of delirium. | Nurses should minimise the duration of urinary catheter use in elderly patients in the emergency department, as prolonged catheter use is associated with prolonged delirium. | The study was conducted at a single academic center. It did not assess long-term outcomes, such as cognitive function or mortality, due to the limited sample size. |

| Reference | Nursing Role | Intervention Type | Clinical Setting | Effect Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Delirium management | Nonpharmacological and pharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [11] | Delirium diagnosis | Delirium diagnosis | non-ICU | positive |

| [12] | Delirium diagnosis | Delirium diagnosis | ICU | positive |

| [13] | Delirium management and preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological, pharmacological and multicomponent | non-ICU | positive |

| [14] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | non-ICU | positive |

| [18] | Delirium diagnosis | Delirium diagnosis | non-ICU | positive |

| [21] | Delirium diagnosis | Delirium diagnosis | ICU | positive |

| [23] | Delirium management | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [36] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | non-ICU | null |

| [37] | Delirium management and preventive interventions | Multicomponent | ICU | positive |

| [38] | Preventive interventions | Multicomponent, nonpharmacological and pharmacological | non-ICU | positive |

| [39] | Delirium management and diagnosis | Nonpharmacological | non-ICU | null |

| [40] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological and pharmacological | ICU | null |

| [41] | Delirium diagnosis | Nonpharmacological and pharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [42] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | non-ICU | positive |

| [43] | Delirium management and preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological and multicomponent | non-ICU | positive |

| [44] | Delirium management and preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological and multicomponent | ICU | positive |

| [45] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | null |

| [46] | Delirium diagnosis | Nonpharmacological and multicomponent | ICU | negative |

| [47] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | null |

| [48] | Preventive interventions | Multicomponent | non-ICU | negative |

| [49] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [50] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological, multicomponent | ICU | positive |

| [51] | Delirium management | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [52] | Delirium management | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [53] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological, multicomponent | ICU | positive |

| [54] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [55] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | null |

| [56] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [57] | Delirium diagnosis | Delirium diagnosis and care for delirium patients | ICU | positive |

| [58] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [59] | Preventive interventions | Multicomponent | non-ICU | positive |

| [60] | Delirium management and diagnosis | Nonpharmacological, multicomponent | non-ICU | positive |

| [61] | Preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | non-ICU | positive |

| [62] | Delirium management and preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological | ICU | positive |

| [63] | Delirium management and preventive interventions | Nonpharmacological, multicomponent | ICU | positive |

| [64] | Preventive interventions | Multicomponent | non-ICU | positive |

| [65] | Preventive interventions | Multicomponent | non-ICU | positive |

| [66] | Delirium diagnosis | Nonpharmacological | non-ICU | null |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szewczak, A.; Siwicka, D.; Klukow, J.; Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J.; Zmorzynski, S. Clinical Nursing Management of Adult Patients with Delirium in a Hospital Setting—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228113

Szewczak A, Siwicka D, Klukow J, Czerwik-Marcinkowska J, Zmorzynski S. Clinical Nursing Management of Adult Patients with Delirium in a Hospital Setting—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228113

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzewczak, Anna, Dorota Siwicka, Jadwiga Klukow, Joanna Czerwik-Marcinkowska, and Szymon Zmorzynski. 2025. "Clinical Nursing Management of Adult Patients with Delirium in a Hospital Setting—A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228113

APA StyleSzewczak, A., Siwicka, D., Klukow, J., Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J., & Zmorzynski, S. (2025). Clinical Nursing Management of Adult Patients with Delirium in a Hospital Setting—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228113