Advancements in Understanding Spasticity: A Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling Perspective

Abstract

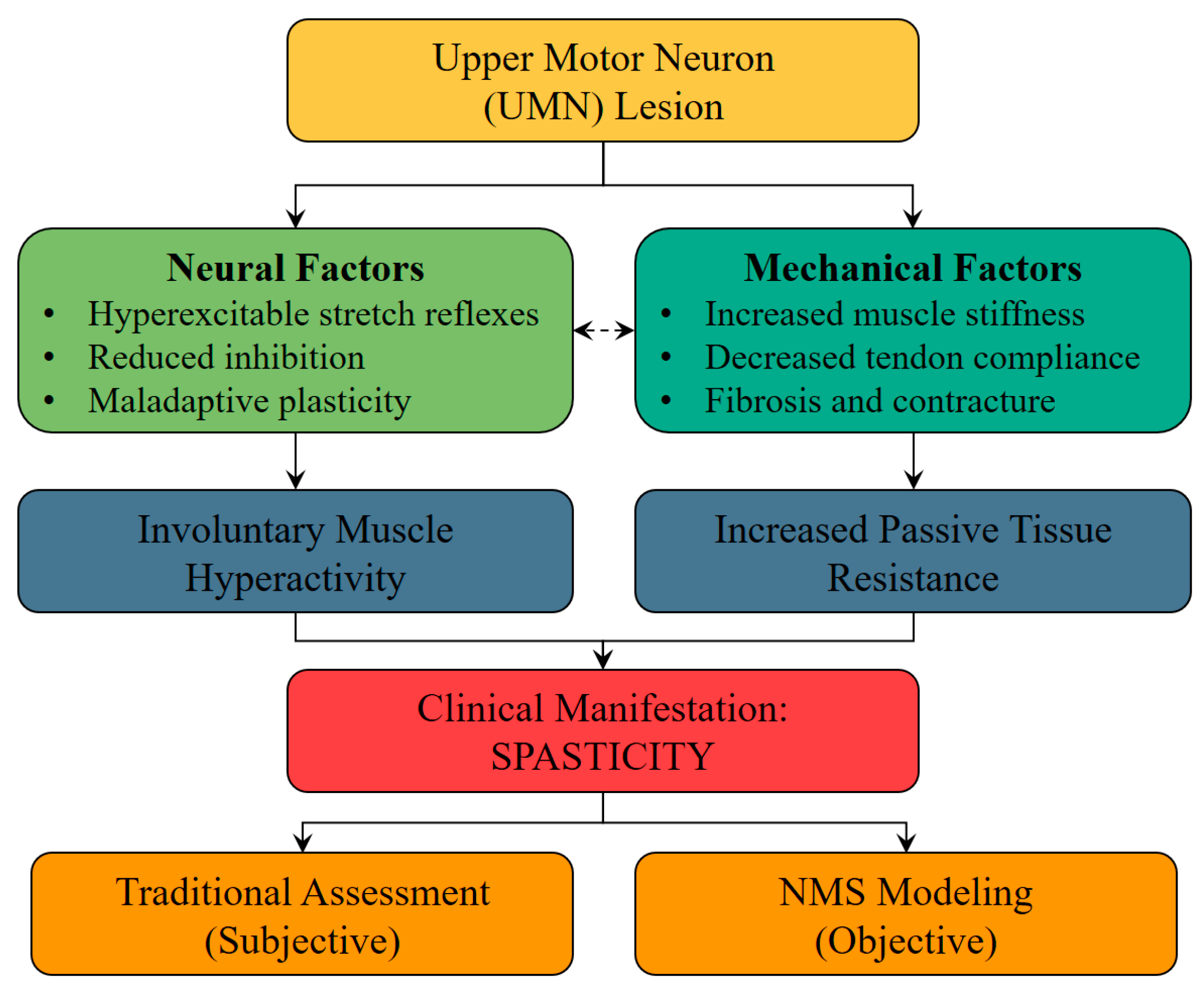

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Spasticity Modeling Approaches

Mechanical, Neurological, and Threshold Control Modeling

3. Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling in Spasticity

3.1. Dynamic Neuromuscular Models

3.2. Physics-Based Simulations

3.3. Clinical Applications

4. Comparing and Evaluating Models

4.1. Metrics for Evaluation

4.2. Integration of Neural and Biomechanical Components

5. Gaps and Future Directions

5.1. Bridging Research and Clinical Practice: Immediate Priorities

5.2. Validation and Standardization: Building Clinical Trust

5.3. Personalized Modeling: Leveraging Advanced Data Sources

5.4. Emerging Technologies: Long-Term Vision

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMS | Neuromusculoskeletal |

| MAS | Modified Ashworth Scale |

| TSRT | Tonic Stretch Reflex Threshold |

| DSRT | Dynamic Stretch Reflex Threshold |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DTI | Diffusion Tensor Imaging |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| CP | Cerebral Palsy |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

References

- Li, S.; Francisco, G.E.; Rymer, W.Z. A new definition of poststroke spasticity and the interference of spasticity with motor recovery from acute to chronic stages. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair. 2021, 35, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stampas, A.; Hook, M.; Korupolu, R.; Jethani, L.; Kaner, M.T.; Pemberton, E.; Li, S.; Francisco, G.E. Evidence of treating spasticity before it develops: A systematic review of spasticity outcomes in acute spinal cord injury interventional trials. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2022, 15, 17562864211070656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressler, D.; Altavista, M.C.; Altenmueller, E.; Bhidayasiri, R.; Bohlega, S.; Chana, P.; Chung, T.M.; Colosimo, C.; Fheodoroff, K.; Garcia-Ruiz, P.J.; et al. Consensus guidelines for botulinum toxin therapy: General algorithms and dosing tables for dystonia and spasticity. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wissel, J.; Schelosky, L.D.; Scott, J.; Christe, W.; Faiss, J.H.; Mueller, J. Early development of spasticity following stroke: A prospective, observational trial. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.A.; Hadjimichael, O.C.; Preiningerova, J.; Vollmer, T.L. Prevalence and treatment of spasticity reported by multiple sclerosis patients. Mult. Scler. J. 2004, 10, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.M.; Hicks, A.L. Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2005, 43, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, T.A.L.; Rethlefsen, S.; Kay, R.M. Prevalence of specific gait abnormalities in children with cerebral palsy: Influence of cerebral palsy subtype, age, and previous surgery. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2005, 25, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne, P.; Coupar, F.; Pollock, A. Motor recovery after stroke: A systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveen, U.; Bautz-Holter, E.; Sandvik, L.; Alvsåker, K.; Røe, C. Relationship between competency in activities, injury severity, and post-concussion symptoms after traumatic brain injury. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2010, 17, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandyan, A.D.; Johnson, G.R.; Price, C.I.M.; Curless, R.H.; Barnes, M.P.; Rodgers, H. A review of the properties and limitations of the Ashworth and modified Ashworth Scales as measures of spasticity. Clin. Rehabil. 1999, 13, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, E.; Ada, L. The Tardieu Scale differentiates contracture from spasticity whereas the Ashworth Scale is confounded by it. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibiglou, L.; Rymer, W.Z.; Harvey, R.L.; Mirbagheri, M.M. The relation between Ashworth scores and neuromechanical measurements of spasticity following stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2008, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, D.G.; Schmit, B.D.; Rymer, W.Z. Effect of muscle biomechanics on the quantification of spasticity. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2001, 29, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, J.W.; Foulds, R.A. Neuromuscular modeling of spasticity in cerebral palsy. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2004, 12, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.K.; Mak, A.F.T. Feasibility of using EMG driven neuromusculoskeletal model for prediction of dynamic movement of the elbow. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2005, 15, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vlugt, E.; De Groot, J.H.; Schenkeveld, K.E.; Arendzen, J.; van Der Helm, F.C.T.; Meskers, C.G.M. The relation between neuromechanical parameters and Ashworth score in stroke patients. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2010, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.F.; Feldman, A.G. The role of stretch reflex threshold regulation in normal and impaired motor control. Brain Res. 1994, 657, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calota, A.; Feldman, A.G.; Levin, M.F. Spasticity measurement based on tonic stretch reflex threshold in stroke using a portable device. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, L.; Aertbeliën, E.; Wambacq, H.; Severijns, D.; Lambrecht, K.; Dan, B.; Huenaerts, C.; Bruyninckx, H.; Janssens, L.; Van Gestel, L.; et al. A clinical measurement to quantify spasticity in children with cerebral palsy by integration of multidimensional signals. Gait Posture 2013, 38, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.J.; Eskinazi, I.; Arias, P.G.; Yack, H.J.; Fregly, B.J. Muscle-driven optimization of walking dynamics for treatment of crouch gait. J. Biomech. 2017, 63, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, M.M.; Li, G.; Shourijeh, M.S.; Ao, D.; Weinschenk, R.C.; Patten, C.; Font-Llagunes, J.M.; Lewis, V.O.; Fregly, B.J. Computational evaluation of psoas muscle influence on walking function following internal hemipelvectomy with reconstruction. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 855870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.; Arami, A. Quantitative modeling of spasticity for clinical assessment, treatment and rehabilitation. Sensors 2020, 20, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falisse, A.; Bar-On, L.; Desloovere, K.; Jonkers, I.; De Groote, F. A spasticity model based on feedback from muscle force explains muscle activity during passive stretches and gait in children with cerebral palsy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Krogt, M.M.; Bar-On, L.; Kindt, T.; Desloovere, K.; Harlaar, J. Neuro-musculoskeletal simulation of instrumented contracture and spasticity assessment in children with cerebral palsy. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2016, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delp, S.L.; Anderson, F.C.; Arnold, A.S.; Loan, P.; Habib, A.; John, C.T.; Guendelman, E.; Thelen, D. GOpenSim: Open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 54, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.; Hicks, J.L.; Uchida, T.K.; Habib, A.; Dembia, C.L.; Dunne, J.J.; Ong, C.F.; Demers, M.S.; Rajagopal, A.; Millard, M.; et al. OpenSim: Simulating musculoskeletal dynamics and neuromuscular control to study human and animal movement. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsgaard, M.; Rasmussen, J.; Christensen, S.T.; Surma, E.; De Zee, M. Analysis of musculoskeletal systems in the AnyBody Modeling System. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2006, 14, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembia, C.L.; Bianco, N.A.; Falisse, A.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. Opensim moco: Musculoskeletal optimal control. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijtenbeek, T. Scone: Open source software for predictive simulation of biological motion. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, C.V.; Williams, S.T.; Vega, M.M.; Ao, D.; Li, G.; Salati, R.M.; Pariser, K.M.; Shourijeh, M.S.; Habib, A.W.; Patten, C.; et al. The Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling Pipeline: MATLAB-based model personalization and treatment optimization functionality for OpenSim. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2025, 22, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling (NMSM) Pipeline: Personalize Models and Design Treatments. Available online: https://nmsm.rice.edu (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Pitto, L.; Kainz, H.; Falisse, A.; Wesseling, M.; Van Rossom, S.; Hoang, H.; Papageorgiou, E.; Hallemans, A.; Desloovere, K.; Molenaers, G.; et al. SimCP: A simulation platform to predict gait performance following orthopedic intervention in children with Cerebral Palsy. Front. Neurorobot. 2019, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzolato, C.; Lloyd, D.G.; Sartori, M.; Ceseracciu, E.; Besier, T.F.; Fregly, B.J.; Reggiani, M. CEINMS: A toolbox to investigate the influence of different neural control solutions on the prediction of muscle excitation and joint moments during dynamic motor tasks. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 3929–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, M.; Refai, M.I.; Gaudio, L.A.; Cop, C.P.; Simonetti, D.; Damonte, F.; Hambly, M.; Lloyd, D.; Pizzolato, C.; Durandau, G.V. Ceinms-rt: An open-source framework for the continuous neuro-mechanical model-based control of wearable robots. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, W.S.; Geyer, H.; Chen, I.-M.; Ang, W.T. Objective assessment of spasticity with a method based on a human upper limb model. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 1414–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cavorzin, P.; Hernot, X.; Bartier, O.; Allain, H.; Carrault, G.; Rochcongar, P.; Chagneau, F. A computed model of the pendulum test of the leg for routine assessment of spasticity in man. ITBM-RBM 2001, 22, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.-S.; Chang, H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, J. Characterization of spastic ankle flexors based on viscoelastic modeling for accurate diagnosis. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2020, 18, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, A.K.; Mullick, A.A.; Moïn-Darbari, K.; Levin, M.F. Tonic stretch reflex threshold as a measure of ankle plantar-flexor spasticity after stroke. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germanotta, M.; Taborri, J.; Rossi, S.; Frascarelli, F.; Palermo, E.; Cappa, P.; Castelli, E.; Petrarca, M. Spasticity measurement based on tonic stretch reflex threshold in children with cerebral palsy using the PediAnklebot. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, N.A.; Feldman, A.G.; Levin, M.F. Stretch-reflex threshold modulation during active elbow movements in post-stroke survivors with spasticity. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falisse, A.; Pitto, L.; Kainz, H.; Hoang, H.; Wesseling, M.; Van Rossom, S.; Papageorgiou, E.; Bar-On, L.; Hallemans, A.; Desloovere, K.; et al. Physics-based simulations to predict the differential effects of motor control and musculoskeletal deficits on gait dysfunction in cerebral palsy: A retrospective case study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Norling, W.R.; Wang, Y. A dynamic neuromuscular model for describing the pendulum test of spasticity. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1997, 44, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, D.; Li, G.; Shourijeh, M.S.; Patten, C.; Fregly, B.J. EMG-driven musculoskeletal model calibration with wrapping surface personalization. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 4235–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, K.P.; D’Incamps, B.L.; Zytnicki, D.; Ting, L.H. Force encoding in muscle spindles during stretch of passive muscle. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fregly, B.J. A Conceptual Blueprint for Making Neuromusculoskeletal Models Clinically Useful. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, V.; van der Krogt, M.M.; Koopman, H.F.J.M.; Verdonschot, N. Sensitivity of subject-specific models to Hill muscle-tendon model parameters in simulations of gait. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shourijeh, M.S.; Mehrabi, N.; McPhee, J.; Fregly, B.J. Advances in Musculoskeletal Modeling and their Application to Neurorehabilitation. Front. Neurorobot. 2020, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shourijeh, M.S.; Fregly, B.J. Muscle Synergies Modify Optimization Estimates of Joint Stiffness During Walking. J. Biomech. Eng. 2020, 142, 011011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shourijeh, M.S.; Ao, D.; Patten, C.; Fregly, B.J. How well do commonly used co-contraction indices approximate lower limb joint stiffness trends during gait for individuals post-stroke? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 588908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, M.; Maculan, M.; Pizzolato, C.; Reggiani, M.; Farina, D. Modeling and simulating the neuromuscular mechanisms regulating ankle and knee joint stiffness during human locomotion. J. Neurophysiol. 2015, 114, 2509–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latash, M.L.; Zatsiorsky, V.M. Joint stiffness: Myth or reality? Hum. Mov. Sci. 1993, 12, 653–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, N.J.; Ada, L.; Neilson, P.D. Spasticity and muscle contracture following stroke. Brain 1996, 119, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinkjær, T.; Magnussen, I. Passive, intrinsic and reflex-mediated stiffness in the ankle extensors of hemiparetic patients. Brain 1994, 117, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquenazi, A.; Mayer, N.; Lee, S.; Brashear, A.; Elovic, E.; Francisco, G.E.; Yablon, S. Patient registry of outcomes in spasticity care. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 91, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, G.E.; McGuire, J.R. Poststroke spasticity management. Stroke 2012, 43, 3132–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissel, J.; Ward, A.B.; Erztgaard, P.; Bensmail, D.; Hecht, M.J.; Lejeune, T.M.; Schnider, P.; Altavista, M.C.; Cavazza, S.; Deltombe, T.; et al. European consensus table on the use of botulinum toxin type A in adult spasticity. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 41, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, F.; Falisse, A. Perspective on musculoskeletal modelling and predictive simulations of human movement to assess the neuromechanics of gait. Proc. R. Soc. B 2021, 288, 20202432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.F.; Piscitelli, D.; Khayat, J. Tonic stretch reflex threshold as a measure of disordered motor control and spasticity—A critical review. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2024, 165, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, D.; Khayat, J.; Feldman, A.G.; Levin, M.F. Clinical Relevance of the Tonic Stretch Reflex Threshold and μ as Measures of Upper Limb Spasticity and Motor Impairment After Stroke. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2025, 39, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, X.; Zhu, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, X. A regression-based framework for quantitative assessment of muscle spasticity using combined EMG and inertial data from wearable sensors. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misgeld, B.J.E.; Lüken, M.; Heitzmann, D.; Wolf, S.I.; Leonhardt, S. Body-sensor-network-based spasticity detection. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2015, 20, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, L.; Barrett, R.; Lichtwark, G. Passive muscle mechanical properties of the medial gastrocnemius in young adults with spastic cerebral palsy. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 2496–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacourpaille, L.; Nordez, A.; Hug, F.; Couturier, A.; Dibie, C.; Guilhem, G. Time-course effect of exercise-induced muscle damage on localized muscle mechanical properties assessed using elastography. Acta Physiol. 2014, 211, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gäverth, J.; Herman, P.A. Changes in the neural and non-neural related properties of the spastic wrist flexors after treatment with botulinum toxin A in post-stroke subjects: An optimization study. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artemiadis, P.K.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. EMG-based control of a robot arm using low-dimensional embeddings. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2010, 26, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durandau, G.; Rampeltshammer, W.F.; van der Kooij, H.; Sartori, M. Neuromechanical model-based adaptive control of bilateral ankle exoskeletons: Biological joint torque and electromyogram reduction across walking conditions. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 1380–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, J.W. The control of muscle tone, reflexes, and movement: Robert Wartenbeg Lecture. Neurology 1980, 30, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorter, A.L.; Richardson, J.K.; Finucane, S.B.; Joshi, V.; Gordon, K.; Rouse, E.J. Characterization and clinical implications of ankle impedance during walking in chronic stroke. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, T.D.; Delgado, M.R.; Gaebler-Spira, D.; Hallett, M.; Mink, J.W.; Task Force on Childhood Motor Disorders. Classification and definition of disorders causing hypertonia in childhood. Pediatrics 2003, 111, e89–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, L.; Aertbeliën, E.; Molenaers, G.; Desloovere, K. Muscle activation patterns when passively stretching spastic lower limb muscles of children with cerebral palsy. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbok, P. Selective dorsal rhizotomy for spastic cerebral palsy: A review. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2007, 23, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlrich, S.D.; Jackson, R.W.; Seth, A.; Kolesar, J.A.; Delp, S.L. Muscle coordination retraining inspired by musculoskeletal simulations reduces knee contact force. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, M.; Llyod, D.G.; Farina, D. Neural data-driven musculoskeletal modeling for personalized neurorehabilitation technologies. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 63, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Momosaki, R.; Niimi, M.; Yamada, N.; Hara, H.; Abo, M. Botulinum toxin therapy combined with rehabilitation for stroke: A systematic review of effect on motor function. Toxins 2019, 11, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, P.B.; Finlayson, H.; Sudol, M.; O’Connor, R. Systematic review of adjunct therapies to improve outcomes following botulinum toxin injection for treatment of limb spasticity. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lannin, N.A.; Ada, L.; English, C.; Ratcliffe, J.; Faux, S.G.; Palit, M.; Gonzalez, S.; Olver, J.; Cameron, I.; Crotty, M.; et al. Effect of additional rehabilitation after botulinum toxin-A on upper limb activity in chronic stroke. Stroke 2020, 51, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, R.L.; Efendy, F.; Teleg, E.S.; Santos, M.M.D.; Rosales, M.C.; Ostrea, M.; Tanglao, M.J.; Ng, A.R. Botulinum toxin as early intervention for spasticity after stroke or non-progressive brain lesion: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 371, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidlauf, T.; Röhrle, O. A multiscale chemo-electro-mechanical skeletal muscle model to analyze muscle contraction and force generation for different muscle fiber arrangements. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrle, O.; Sprenger, M.; Schmitt, S. A two-muscle, continuum-mechanical forward simulation of the upper limb. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2017, 16, 743–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No increase in muscle tone |

| 1 | Slight increase in muscle tone, minimal resistance at end of range of motion (ROM) |

| 1+ | Slight increase in muscle tone, catch followed by minimal resistance through less than half of ROM |

| 2 | More marked increase in muscle tone through most of ROM, but affected part easily moved |

| 3 | Considerable increase in muscle tone, passive movement difficult |

| 4 | Affected part rigid in flexion or extension |

| Velocity of Movement | Quality of Muscle Reaction (Grade) | Description | Angle of Catch (R1)/PROM (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1: Slow (as slow as possible) | N/A (or “No spastic reaction expected”) | Baseline measurement of passive range of motion (PROM) under minimal stretch reflex activation. | R2 (Angle of full PROM) is recorded. No R1 (catch) is expected. |

| V2: Medium (limb falling under gravity) | A grade (0–4) is assigned based on the observed muscle response. | Assesses muscle response to stretch at a moderate speed. A catch (R1) indicates spasticity. | R1 (Angle of catch) is recorded if present. |

| V3: Fast (as fast as possible) | A grade (0–4) is assigned based on the observed muscle response. | Assesses muscle response to stretch at a fast speed. Elicits velocity-dependent spasticity (catch/clonus). | R1 (Angle of catch or clonus) is recorded if present. |

| Model Type | Key Features | Strengths | Limitations | Clinical Applicability | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Spring–damper analogs, passive tissue modeling | Simple to implement; effective for capturing passive stiffness | Does not model neural dynamics; limited to low-velocity tasks | Passive assessments, e.g., pendulum tests | Pendulum tests for elbow stiffness |

| Neurological | Reflex pathways, neural gain, feedback delays | Simulates neural contributions; useful for studying reflexes | Lacks biomechanical realism; often population-averaged parameters | Understanding reflex hyperexcitability | Identifying reflex triggers in stroke |

| Threshold Control | TSRT/DSRT reflex thresholds based on joint angle/velocity | Quantifies reflex triggers; applicable during passive movements | Requires biomechanical integration for task-level simulation | Botulinum toxin targeting; spasticity quantification | Optimizing injection sites in CP |

| Hybrid | Combines neural and mechanical elements | Simulates reflex–mechanical interactions | Often low-dimensional; not fully personalized | Simulated resistance during clinical tasks | Modeling elbow catch in stroke |

| Personalized NMS | Patient-specific anatomy, EMG, multiscale modeling | High anatomical fidelity; predicts functional outcomes | Computationally intensive; requires technical expertise | Diagnosis, treatment planning, outcome prediction | Gait optimization in CP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shourijeh, M.S.; Stampas, A.; Chang, S.-H.; Korupolu, R.; Francisco, G.E. Advancements in Understanding Spasticity: A Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228092

Shourijeh MS, Stampas A, Chang S-H, Korupolu R, Francisco GE. Advancements in Understanding Spasticity: A Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228092

Chicago/Turabian StyleShourijeh, Mohammad S., Argyrios Stampas, Shuo-Hsiu Chang, Radha Korupolu, and Gerard E. Francisco. 2025. "Advancements in Understanding Spasticity: A Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling Perspective" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228092

APA StyleShourijeh, M. S., Stampas, A., Chang, S.-H., Korupolu, R., & Francisco, G. E. (2025). Advancements in Understanding Spasticity: A Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228092