Sustainable Ultralightweight U-Net-Based Architecture for Myocardium Segmentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel ultralightweight U-Net-based model tailored for myocardium segmentation;

- We introduce a new dataset with manually segmented cardiac muscle areas, validated by specialists, which is publicly available from GitHub;

- We demonstrate comparable segmentation accuracy in terms of IoU and Dice coefficients, alongside significant reductions in model complexity and parameter count;

- Our work aligns with the Green AI trend by considering not only accuracy but also model size, computational complexity, and operational efficiency. We provide a thorough quantitative analysis of the model’s sustainability using FLOPs and parameter counts.

2. Related Work

2.1. Medical Image Segmentation

2.2. Green AI

3. Materials and Methods

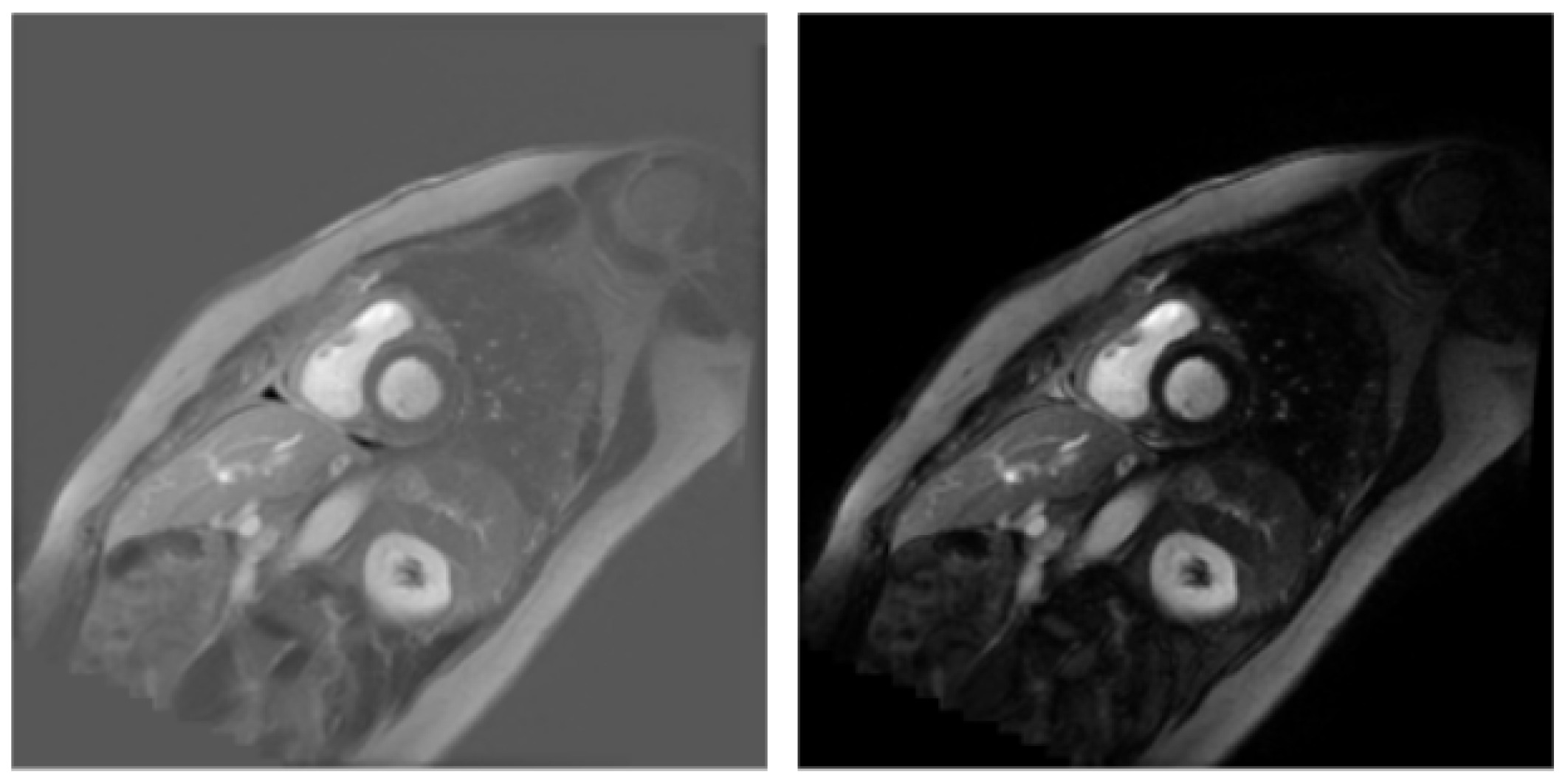

3.1. Dataset

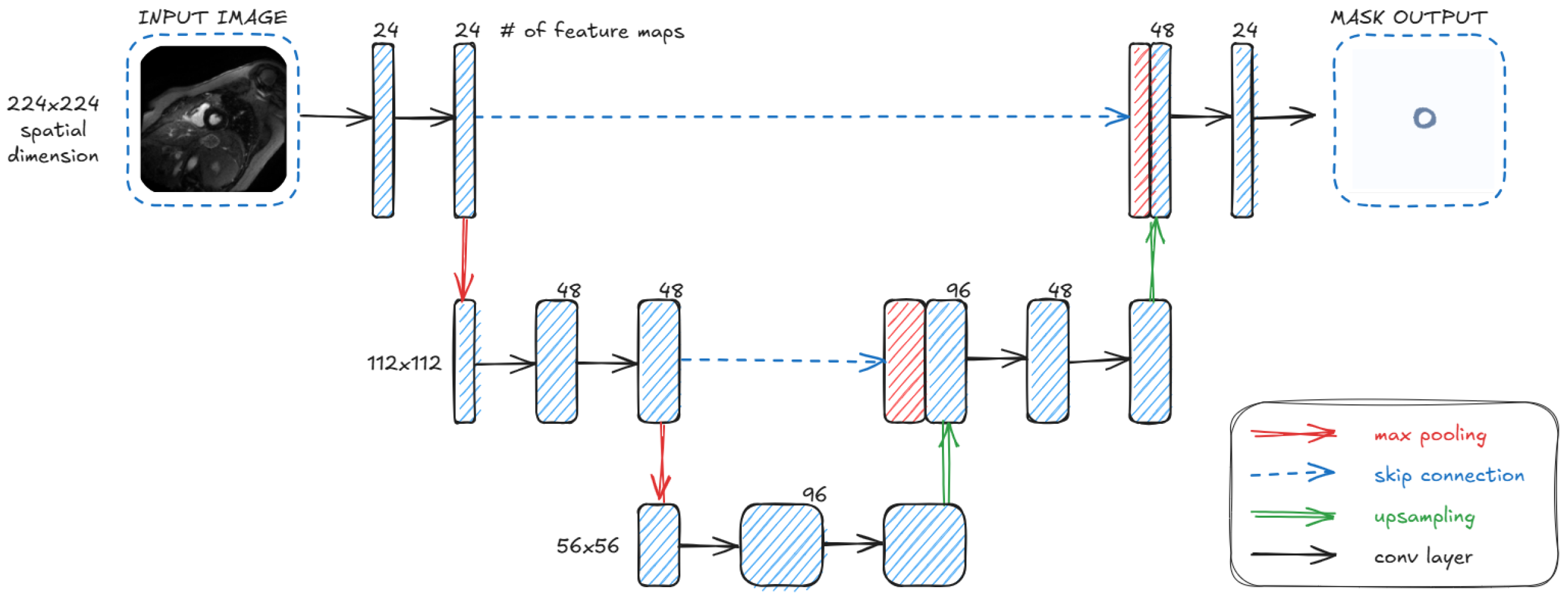

3.2. Architecture

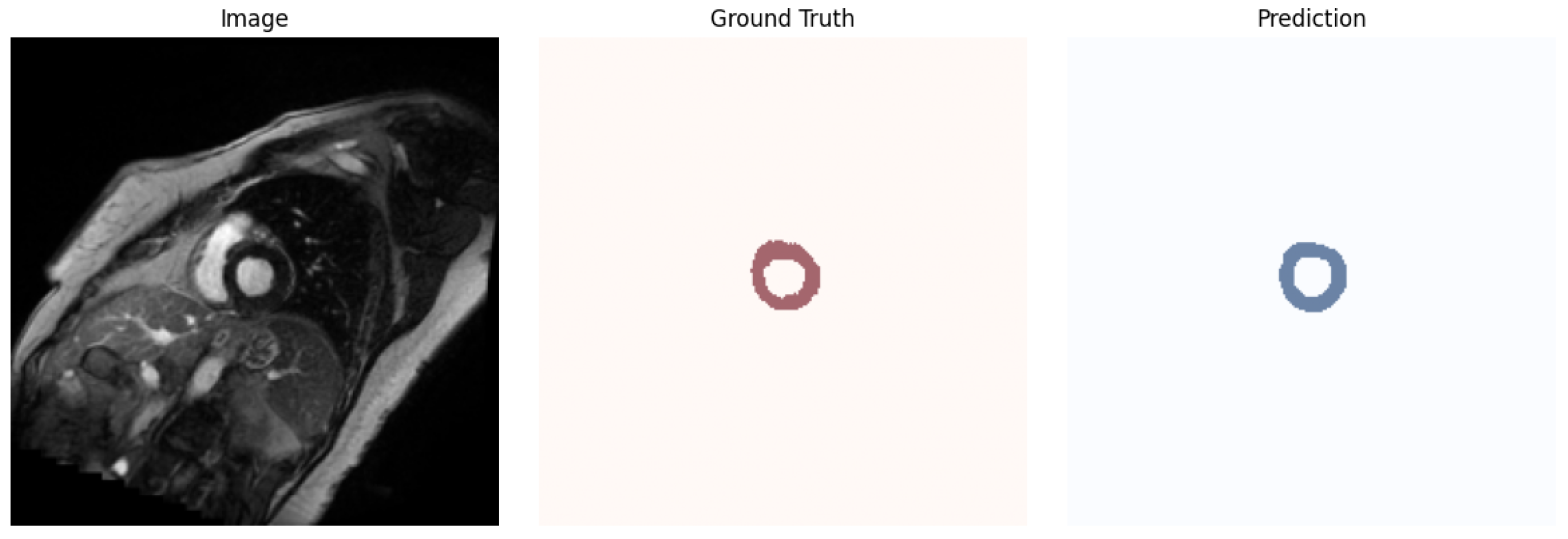

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

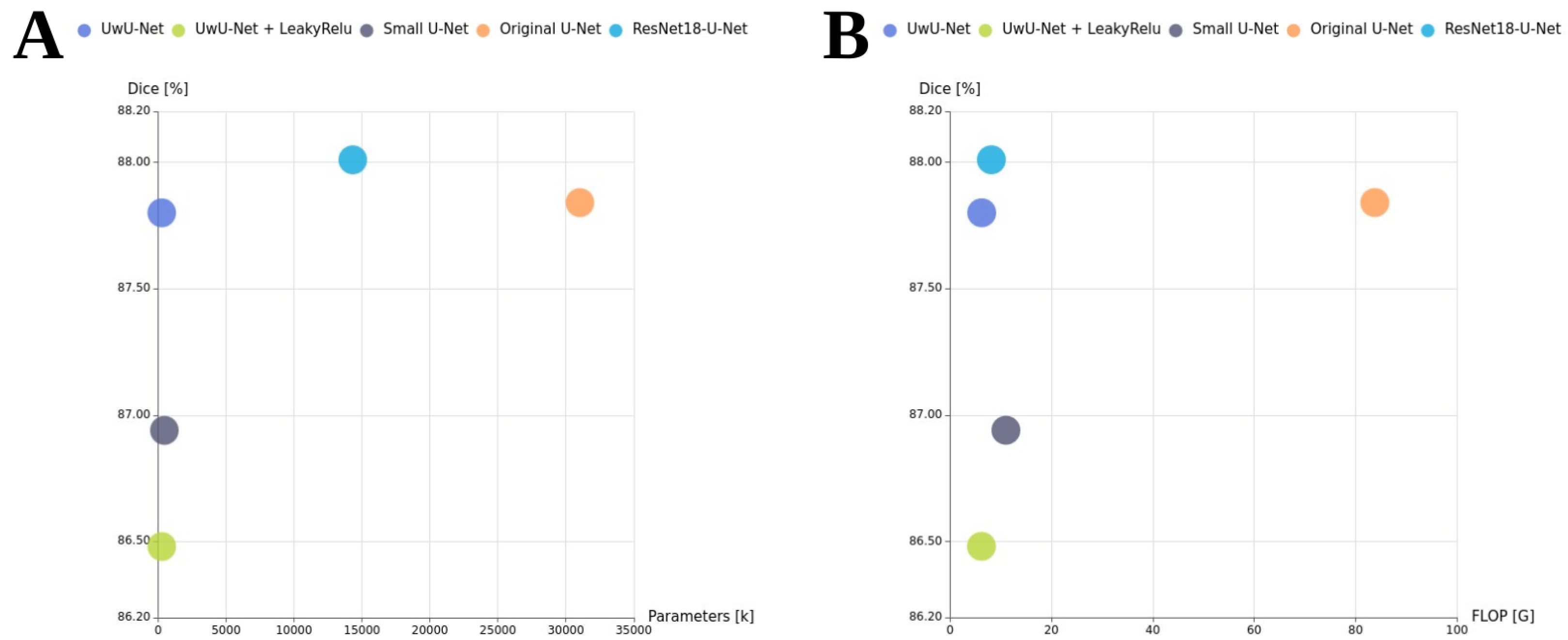

4.2. Obtained Results

- ResNet18-U-Net: This model follows the standard U-Net decoder architecture but uses a ResNet18 encoder. It contains approximately 14.3 million parameters. By using a ResNet18 backbone, the model can benefit from transfer learning, leveraging features learned from large-scale datasets such as ImageNet. The decoder is a custom upsampling path designed to match the feature maps from the ResNet layers via skip connections.

- Original U-Net: A widely used baseline architecture with four downsampling and four upsampling blocks, each composed of double convolution layers [28]. It was originally designed for biomedical image segmentation.

- Small U-Net: A simplified version of U-Net architecture with only two downsampling and two upsampling blocks.

- UwU-Net (Proposed): A lightweight version of U-Net with a reduced number of layers and parameters, making it almost twice as light as Small U-Net.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

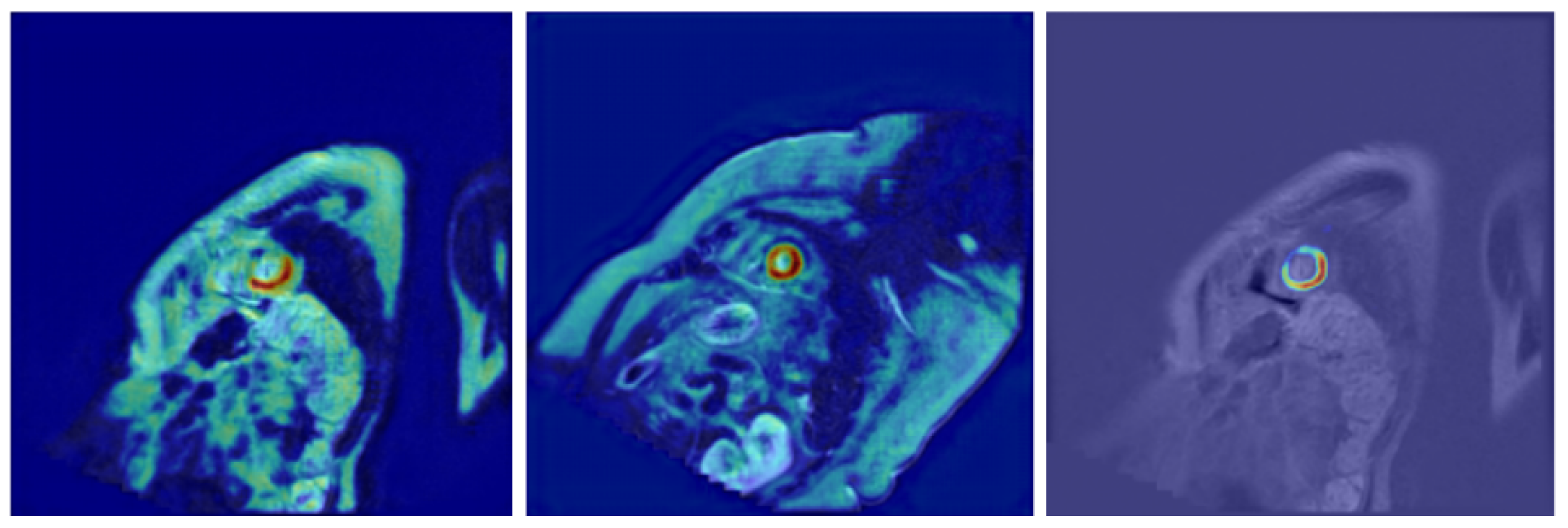

- Further model explainability—In the current work, we have integrated explainability techniques into our architecture, incorporating Grad-CAM visualizations to highlight the image regions that most significantly influenced the segmentation output. These visualizations not only improve trust in the model’s decisions but also provide valuable feedback for clinicians by revealing patterns that are consistent with anatomical structures. Future work may extend this approach by exploring additional methods, such as integrated gradients or layer-wise relevance propagation, to provide complementary perspectives on model reasoning and further enhance clinical interpretability.

- Further energy-aware optimization—Although the proposed model demonstrates competitive performance, further optimization with respect to energy efficiency remains an important issue for future work. Advanced hyperparameter tuning or model pruning strategies could be employed to reduce the computational cost (e.g., FLOPs and total number of parameters) while potentially maintaining or even improving the segmentation performance. This is particularly relevant in the context of sustainable AI and deployment in resource-constrained environments.

- Extension to diagnostic classification systems—The current segmentation architecture could be extended to support classification tasks. For instance, by analyzing the segmented myocardium, the system could assist in detecting specific cardiac pathologies (e.g., myocardial infarction, fibrosis, or inflammation) based on extracted textural or morphological features. Integrating segmentation with classification may provide a comprehensive diagnostic pipeline that enhances clinical decision-making.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Y.; Dang, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Bai, X. 3-D contour-aware U-Net for efficient rectal tumor segmentation in magnetic resonance imaging. Med. Eng. Phys. 2025, 140, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, B.; Navazo, I.; Brunet, P.; Monclús, E.; Bendezú, Á.; Azpiroz, F. Automatic colon segmentation on T1-FS MR images. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2025, 123, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleszewski, J.J.; Lai, C.K.; Nair, V.; Veinot, J.P. Anatomic considerations and examination of cardiovascular specimens (excluding devices). In Cardiovascular Pathology, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 27–84. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Miron, A.; Hone, K.; Li, Y. Segmenting medical images: From UNet to Res-UNet and nnUNet. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 37th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Guadalajara, Mexico, 26–28 June 2024; pp. 483–489. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, R.; Aghdam, E.K.; Rauland, A.; Jia, Y.; Avval, A.H.; Bozorgpour, A.; Karimijafarbigloo, S.; Cohen, J.P.; Adeli, E.; Merhof, D. Medical image segmentation review: The success of U-Net. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 10076–10095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petmezas, G.; Papageorgiou, V.E.; Vassilikos, V.; Pagourelias, E.; Tsaklidis, G.; Katsaggelos, A.K.; Maglaveras, N. Recent advancements and applications of deep learning in heart failure: A systematic review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 176, 108557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, S.; Dreżewski, R. Modified histogram equalization for improved CNN medical image segmentation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 225, 3021–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Huang, H.; Xia, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X. Automatic segmentation method using FCN with multi-scale dilated convolution for medical ultrasound image. Vis. Comput. 2023, 39, 5953–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, P.; Sharma, D.; Yadav, K.; Sethi, T. Enhancing Medical Image Segmentation with Recurrent Neural Network Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Disruptive Technologies (ICDT), Greater Noida, India, 15–16 March 2024; pp. 824–830. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Wu, L.M.; Xia, Y. Towards accurate cardiac MRI segmentation with variational autoencoder-based unsupervised domain adaptation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 2924–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Hong, M.; Ji, W.; Fu, H.; Xu, Y.; Xu, M.; Jin, Y. Medical SAM Adapter: Adapting Segment Anything Model for Medical Image Segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2025, 102, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Cui, C.; Liu, Q.; Yao, T.; Remedios, L.W.; Bao, S.; Landman, B.A.; Wheless, L.E.; Coburn, L.A.; Wilson, K.T.; et al. Segment Anything Model (SAM) for Digital Pathology: Assess Zero-shot Segmentation on Whole Slide Imaging. In Proceedings of the IS&T International Symposium on Electronic Imaging, Burlingame, CA, USA, 2–6 February 2025; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Y. Improving myocardial pathology segmentation with U-Net++ and EfficientSeg from multi-sequence cardiac magnetic resonance images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 151, 106218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.F.S.D.; Silva, A.C.; Paiva, A.C.D.; Gattass, M.; Cunha, A.M. A Multi-Stage Automatic Method Based on a Combination of Fully Convolutional Networks for Cardiac Segmentation in Short-Axis MRI. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y. nnformer: Volumetric medical image segmentation via a 3d transformer. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 4036–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, H.; Zeng, D.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zhuang, J.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Myocardial segmentation of cardiac MRI sequences with temporal consistency for coronary artery disease diagnosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 804442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouei, E.; Pan, S.; Hu, M.; Kesarwala, A.H.; Qiu, R.L.; Zhou, J.; Roper, J.; Yang, X. Cardiac MRI segmentation using shifted-window multilayer perceptron mixer networks. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 115048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-antari, M.A.; Shaaf, Z.F.; Jamil, M.M.A.; Samee, N.A.; Alkanhel, R.; Talo, M.; Al-Huda, Z. Deep learning myocardial infarction segmentation framework from cardiac magnetic resonance images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 89, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Huang, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, L. Selective and multi-scale fusion mamba for medical image segmentation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 261, 125518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Zhou, H.Y.; Yu, L.; Liang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, H.; Wang, S. Swin-UMamba†: Adapting Mamba-based vision foundation models for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 44, 3898–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Z.; Ye, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. Segmamba: Long-range sequential modeling mamba for 3D medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 578–588. [Google Scholar]

- Bolón-Canedo, V.; Morán-Fernández, L.; Cancela, B.; Alonso-Betanzos, A. A Review of Green Artificial Intelligence: Towards a More Sustainable Future. Neurocomputing 2024, 599, 128096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.; Dodge, J.; Smith, N.A.; Etzioni, O. Green AI. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbierato, E.; Gatti, A. Toward Green AI: A Methodological Survey of the Scientific Literature. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23989–24013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia, R.; Sallou, J.; Cruz, L. A Systematic Review of Green AI. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2023, 13, e1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboshosha, A. AI based medical imagery diagnosis for COVID-19 disease examination and remedy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI 2015), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlicka, A.; Pawlicki, M.; Jaroszewska-Choraś, D.; Kozik, R.; Choraś, M. Enhancing Clinical Trust: The Role of AI Explainability in Transforming Healthcare. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–12 December 2024; pp. 543–549. [Google Scholar]

| Model | Avg. | Min. | Max. | Std.dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UwU-Net (proposed) | 0.7889 | 0.7686 | 0.8173 | 0.0168 |

| UwU-Net + LeakyRelu (proposed) | 0.7697 | 0.7075 | 0.8139 | 0.0286 |

| Small U-Net | 0.7769 | 0.7347 | 0.8097 | 0.0195 |

| Original U-Net | 0.7896 | 0.7534 | 0.8154 | 0.0176 |

| ResNet18-U-Net | 0.7909 | 0.7787 | 0.8007 | 0.0076 |

| Model | Avg. | Min. | Max. | Std.dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UwU-Net (proposed) | 0.8780 | 0.8618 | 0.8938 | 0.0109 |

| UwU-Net + LeakyRelu (proposed) | 0.8648 | 0.8203 | 0.8920 | 0.0198 |

| Small U-Net | 0.8694 | 0.8343 | 0.8888 | 0.0153 |

| Original U-Net | 0.8784 | 0.8466 | 0.8926 | 0.0142 |

| ResNet18-U-Net | 0.8801 | 0.8713 | 0.8879 | 0.0058 |

| Model | FLOP [G] | Parameters [M] |

|---|---|---|

| UwU-Net (proposed) | 6.24 | 0.263 |

| UwU-Net + LeakyRelu (proposed) | 6.22 | 0.263 |

| Small U-Net | 11.02 | 0.467 |

| Original U-Net | 83.79 | 31.042 |

| ResNet18-U-Net | 8.16 | 14.321 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filarecki, J.; Mockiewicz, D.; Giełczyk, A.; Kuźba-Kryszak, T.; Makarewicz, R.; Lewandowski, M.; Serafin, Z. Sustainable Ultralightweight U-Net-Based Architecture for Myocardium Segmentation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7971. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227971

Filarecki J, Mockiewicz D, Giełczyk A, Kuźba-Kryszak T, Makarewicz R, Lewandowski M, Serafin Z. Sustainable Ultralightweight U-Net-Based Architecture for Myocardium Segmentation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7971. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227971

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilarecki, Jakub, Dorota Mockiewicz, Agata Giełczyk, Tamara Kuźba-Kryszak, Roman Makarewicz, Marek Lewandowski, and Zbigniew Serafin. 2025. "Sustainable Ultralightweight U-Net-Based Architecture for Myocardium Segmentation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7971. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227971

APA StyleFilarecki, J., Mockiewicz, D., Giełczyk, A., Kuźba-Kryszak, T., Makarewicz, R., Lewandowski, M., & Serafin, Z. (2025). Sustainable Ultralightweight U-Net-Based Architecture for Myocardium Segmentation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7971. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227971