Comprehensive Evaluation of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Paediatric Cystic Fibrosis: Nutritional, Pulmonary, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes †

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Nutritional Status Measurements

2.3. Pulmonary Function Measurements

2.4. Health-Related Quality of Life Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

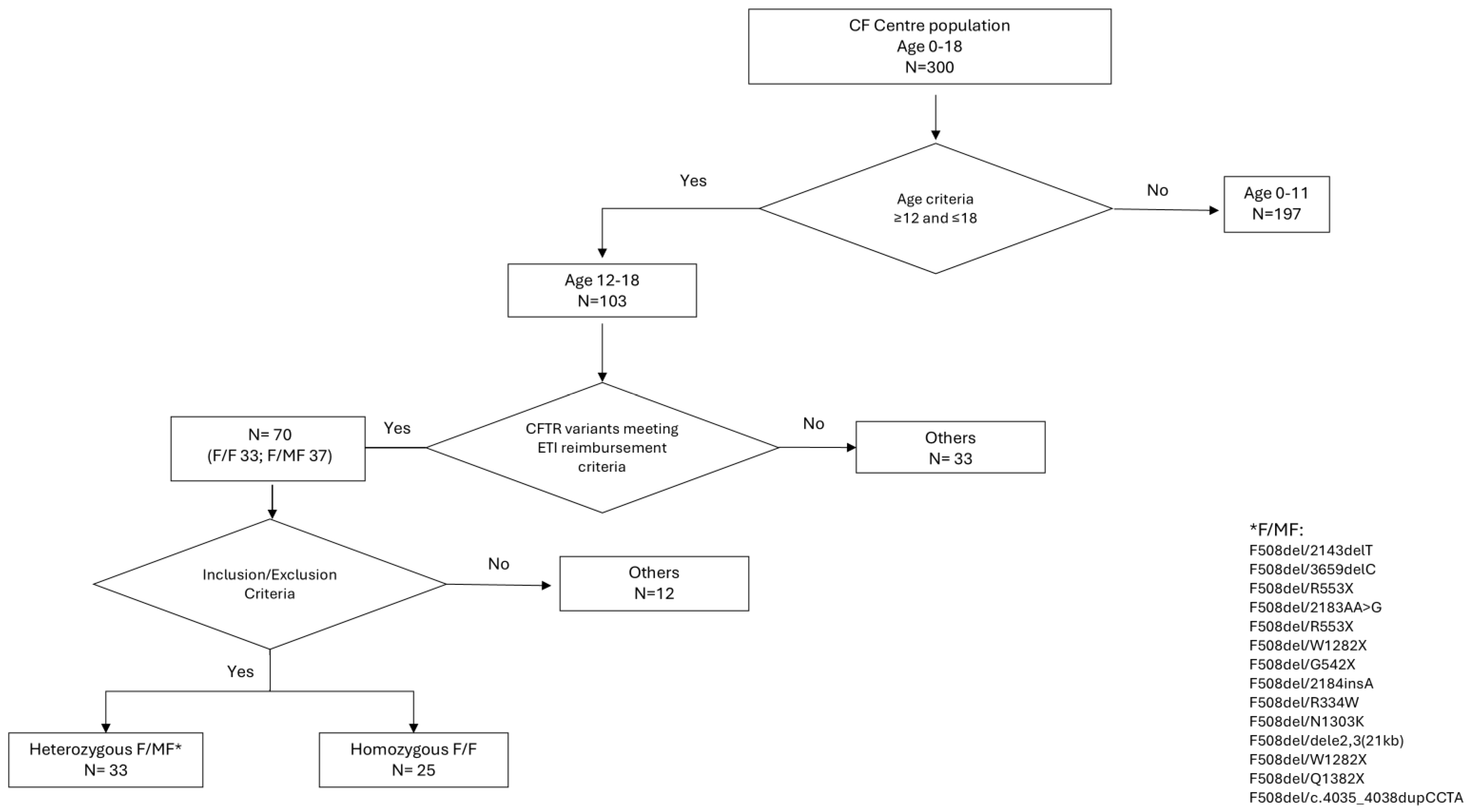

3.1. Subjects’ Characteristics

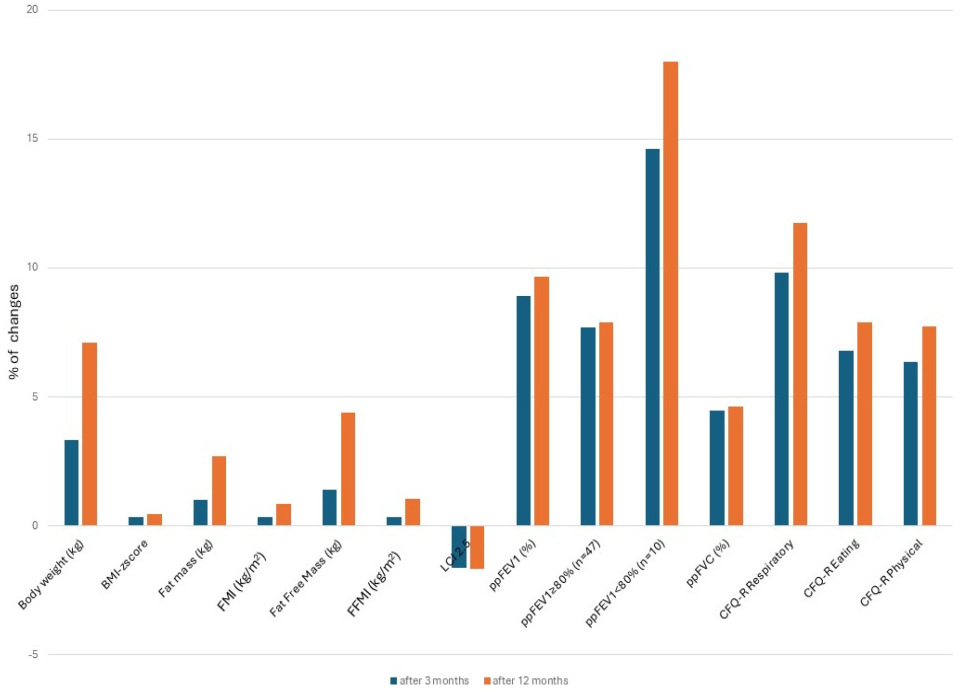

3.2. Nutritional Status Assessment

3.3. Pulmonary Function Assessment

3.4. Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

3.5. Assessment of the Relationship Between Pulmonary Function, Nutritional Status, and Quality of Life

3.5.1. Pulmonary Function and Nutritional Status

3.5.2. Pulmonary Function and Quality of Life

3.5.3. Nutritional Status and Quality of Life

4. Discussion

4.1. Nutritional Aspects

4.2. Pulmonary Aspects

4.3. Psychological Aspects

4.4. Correlations Between Lung Function, Nutritional Status, and Psychological Well-Being

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Southern, K.W.; Castellani, C.; Lammertyn, E.; Smyth, A.; VanDevanter, D.; van Koningsbruggen-Rietschel, S.; Barben, J.; Bevan, A.; Brokaar, E.; Collins, S.; et al. Standards of care for CFTR variant-specific therapy (including modulators) for people with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, B.W.; Davies, J.; McElvaney, N.G.; Tullis, E.; Bell, S.C.; Dřevínek, P.; Griese, M.; McKone, E.F.; Wainwright, C.E.; Konstan, M.W.; et al. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, P.G.; Mall, M.A.; Dřevínek, P.; Lands, L.C.; McKone, E.F.; Polineni, D.; Ramsey, B.W.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; Tullis, E.; Vermeulen, F.; et al. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; Munck, A.; McKone, E.F.; Van Der Ent, C.K.; Moeller, A.; Simard, C.; Wang, L.T.; Ingenito, E.P.; McKee, C.; Lu, Y.; et al. Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis Homozygous for Phe508del. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2013–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstan, M.W.; McKone, E.F.; Moss, R.B.; Marigowda, G.; Tian, S.; Waltz, D.; Huang, X.; Lubarsky, B.; Rubin, J.; Millar, S.J.; et al. Assessment of safety and efficacy of long-term treatment with combination lumacaftor and ivacaftor therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation (PROGRESS): A phase 3, extension study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, B.; Li, W.; Li, P. Efficacy and Safety of Triple Combination Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Modulators in Patients With Cystic Fibrosis: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 863280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkova, N.; Moy, K.; Evans, J.; Campbell, D.; Tian, S.; Simard, C.; Higgins, M.; Konstan, M.W.; Sawicki, G.S.; Elbert, A.; et al. Disease progression in patients with cystic fibrosis treated with ivacaftor: Data from national US and UK registries. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2020, 19, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagenais, R.V.E.; Su, V.C.H.; Quon, B.S. Real-World Safety of CFTR Modulators in the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, M.; Kavvalou, A.; Welsner, M.; Hirtz, R.; Straßburg, S.; Sutharsan, S.; Stehling, F.; Steindor, M. Real-life impact of highly effective CFTR modulator therapy in children with cystic fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1176815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuek, S.; McCullagh, A.; Paul, E.; Armstrong, D. Real world outcomes of CFTR modulator therapy in Australian adults and children. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 82, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.K.; Volkova, N.; Ahluwalia, N.; Sahota, G.; Xuan, F.; Chin, A.; Weinstock, T.G.; Ostrenga, J.; Elbert, A. Real-world safety and effectiveness of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in people with cystic fibrosis: Interim results of a long-term registry-based study. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapouni, N.; Moustaki, M.; Douros, K.; Loukou, I. Efficacy and Safety of Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis: A Systematic Review. Children 2023, 10, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.P.; Paynter, A.C.; Heltshe, S.L.; Donaldson, S.H.; Frederick, C.A.; Freedman, S.D.; Gelfond, D.; Hoffman, L.R.; Kelly, A.; Narkewicz, M.R.; et al. Clinical Effectiveness of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in People with Cystic Fibrosis: A Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutharsan, S.; Dillenhoefer, S.; Welsner, M.; Stehling, F.; Brinkmann, F.; Burkhart, M.; Ellemunter, H.; Dittrich, A.-M.; Smaczny, C.; Eickmeier, O.; et al. Impact of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on lung function, nutritional status, pulmonary exacerbation frequency and sweat chloride in people with cystic fibrosis: Real-world evidence from the German CF Registry. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 32, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilschanski, M.; Munck, A.; Carrion, E.; Cipolli, M.; Collins, S.; Colombo, C.; Declercq, D.; Hatziagorou, E.; Hulst, J.; Kalnins, D.; et al. ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS guideline on nutrition care for cystic fibrosis. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 413–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgel, P.-R.; Southern, K.W.; Addy, C.; Battezzati, A.; Berry, C.; Bouchara, J.-P.; Brokaar, E.; Brown, W.; Azevedo, P.; Durieu, I.; et al. Standards for the care of people with cystic fibrosis (CF); recognising and addressing CF health issues. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2024, 23, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, L.S.; Marciel, K.K.; Quittner, A.L. Utilization of patient-reported outcomes as a step towards collaborative medicine. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2013, 14, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, C.; Duff, A.J.; Bell, S.C.; Heijerman, H.G.; Munck, A.; Ratjen, F.; Sermet-Gaudelus, I.; Southern, K.W.; Barben, J.; Flume, P.A.; et al. ECFS best practice guidelines: The 2018 revision. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2018, 17, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walicka-Serzysko, K.; Borawska-Kowalczyk, U.; Postek, M.; Milczewska, J.; Zybert, K.; Woźniacki, Ł.; Mielus, M.; Wołkowicz, A.; Żabińska-Jaroń, A.; Matusiak, J.; et al. Real-life impact of CFTR modulator therapy on respiratory system in children with cystic fibrosis. In Proceedings of the 47th European Cystic Fibrosis Conference, Glasgow, UK, 5–8 June 2024; p. S101. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, P.M.; Rosenstein, B.J.; White, T.B.; Accurso, F.J.; Castellani, C.; Cutting, G.R.; Durie, P.R.; Legrys, V.A.; Massie, J.; Parad, R.B.; et al. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J. Pediatr. 2008, 153, S4–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boeck, K.; Wilschanski, M.; Castellani, C.; Taylor, C.; Cuppens, H.; Dodge, J.; Sinaasappel, M.; Group, D.W. Cystic fibrosis: Terminology and diagnostic algorithms. Thorax 2006, 61, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, C.; Simmonds, N.J.; Barben, J.; Addy, C.; Bevan, A.; Burgel, P.R.; Drevinek, P.; Gartner, S.; Gramegna, A.; Lammertyn, E.; et al. Standards for the care of people with cystic fibrosis (CF): A timely and accurate diagnosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ecfs.eu/sites/default/files/VariablesDefinitionsAS_V9_ECFSPR_20241121.pdf. (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Robinson, P.D.; Latzin, P.; Verbanck, S.; Hall, G.L.; Horsley, A.; Gappa, M.; Thamrin, C.; Arets, H.G.; Aurora, P.; Fuchs, S.I.; et al. Consensus statement for inert gas washout measurement using multiple- and single- breath tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 41, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapletal, A.; Samanek, M.; Paul, T. Lung Function in Children and Adolescents: Methods, Reference Values; Karger: Basel, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beydon, N.; Davis, S.D.; Lombardi, E.; Allen, J.L.; Arets, H.G.; Aurora, P.; Bisgaard, H.; Davis, G.M.; Ducharme, F.M.; Eigen, H.; et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Pulmonary function testing in preschool children. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 1304–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Crapo, R.; Enright, P.; van der Grinten, C.P.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.; Zheng, J.; et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: The global lung function 2012 equations. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, B.L.; Steenbruggen, I.; Miller, M.R.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Cooper, B.G.; Hall, G.L.; Hallstrand, T.S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; McCarthy, K.; McCormack, M.C.; et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, D.; Borawska-Kowalczyk, U. Polska adaptacja Kwestionariusza Jakości Życia przeznaczonego dla dzieci i dorosłych chorych na mukowiscydozę oraz ich rodziców (CFQ-R). Pediatr. Pol. 2009, 84, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quittner, A.L.; Sawicki, G.S.; McMullen, A.; Rasouliyan, L.; Pasta, D.J.; Yegin, A.; Konstan, M.W. Erratum to: Psychometric evaluation of the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised in a national, US sample. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quittner, A.L.; Modi, A.C.; Wainwright, C.; Otto, K.; Kirihara, J.; Montgomery, A.B. Determination of the minimal clinically important difference scores for the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised respiratory symptom scale in two populations of patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection. Chest 2009, 135, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; Robinson, P.D.; Shteinberg, M.; Downey, D.G. CFTR modulator therapy: Transforming the landscape of clinical care in cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2023, 402, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meoli, A.; Fainardi, V.; Deolmi, M.; Chiopris, G.; Marinelli, F.; Caminiti, C.; Esposito, S.; Pisi, G. State of the Art on Approved Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Cárdenes, C.M.; Merino Sánchez-Cañete, A.; Vicente Santamaría, S.; Gascón Galindo, C.; Merino Sanz, N.; Tabares González, A.; Blitz Castro, E.; Morales Tirado, A.; Garriga García, M.; López Rozas, M.; et al. Effects on growth, weight and body composition after CFTR modulators in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 3632–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boat, T.; Hossain, M.M.; Nakamura, A.; Hjelm, M.; Hardie, W.; Wackler, M.; Amato, A.; Dress, C. Growth, Body Composition, and Strength of Children With Cystic Fibrosis Treated With Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor (ETI). Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2025, 60, e27463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaud, R.; Languepin, J.; Lagarrigue, M.; Arrouy, A.; Macey, J.; Bui, S.; Dupuis, M.; Roditis, L.; Flumian, C.; Mas, E.; et al. Dietary intake remains unchanged while nutritional status improves in children and adults with cystic fibrosis on Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 50, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijerman, H.G.M.; McKone, E.F.; Downey, D.G.; Van Braeckel, E.; Rowe, S.M.; Tullis, E.; Mall, M.A.; Welter, J.J.; Ramsey, B.W.; McKee, C.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: A double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1940–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connett, G.; Maguire, S.; Larcombe, T.; Scanlan, N.; Shinde, S.; Muthukumarana, T.; Bevan, A.; Keogh, R.; Legg, J. Real-world impact of Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor treatment in young people with Cystic Fibrosis: A longitudinal study. Respir. Med. 2025, 236, 107882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanick, E.T.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; Davies, J.; Gibson, R.L.; Mall, M.A.; McKone, E.F.; McNally, P.; Ramsey, B.W.; Rayment, J.H.; Rowe, S.M.; et al. A Phase 3 Open-Label Study of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Children 6 through 11 Years of Age with Cystic Fibrosis and at Least One. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralski, J.L.; Hoppe, J.E.; Mall, M.A.; McColley, S.A.; McKone, E.; Ramsey, B.; Rayment, J.H.; Robinson, P.; Stehling, F.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; et al. Phase 3 Open-Label Clinical Trial of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Children Aged 2–5 Years with Cystic Fibrosis and at Least One. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graeber, S.Y.; Renz, D.M.; Stahl, M.; Pallenberg, S.T.; Sommerburg, O.; Naehrlich, L.; Berges, J.; Dohna, M.; Ringshausen, F.C.; Doellinger, F.; et al. Effects of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor Therapy on Lung Clearance Index and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streibel, C.; Willers, C.C.; Pusterla, O.; Bauman, G.; Stranzinger, E.; Brabandt, B.; Bieri, O.; Curdy, M.; Bullo, M.; Frauchiger, B.S.; et al. Effects of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy in children with cystic fibrosis—A comprehensive assessment using lung clearance index, spirometry, and functional and structural lung MRI. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, M.; Dohna, M.; Graeber, S.Y.; Sommerburg, O.; Renz, D.M.; Pallenberg, S.T.; Voskrebenzev, A.; Schütz, K.; Hansen, G.; Doellinger, F.; et al. Impact of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy on lung clearance index and magnetic resonance imaging in children with cystic fibrosis and one or two. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2400004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, P.J.; Mall, M.A.; Álvarez, A.; Colombo, C.; de Winter-de Groot, K.M.; Fajac, I.; McBennett, K.A.; McKone, E.F.; Ramsey, B.W.; Sutharsan, S.; et al. Triple Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMango, E.; Spielman, D.B.; Overdevest, J.; Keating, C.; Francis, S.F.; Dansky, D.; Gudis, D.A. Effect of highly effective modulator therapy on quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnovale, V.; Iacotucci, P.; Terlizzi, V.; Colangelo, C.; Ferrillo, L.; Pepe, A.; Francalanci, M.; Taccetti, G.; Buonaurio, S.; Celardo, A.; et al. Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis Homozygous for the. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziano, S.; Boldrini, F.; Pellicano, G.R.; Milo, F.; Majo, F.; Cristiani, L.; Montemitro, E.; Alghisi, F.; Bella, S.; Cutrera, R.; et al. Longitudinal Effects of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor: Multidimensional Assessment of Neuropsychological Side Effects and Physical and Mental Health Outcomes in Adolescents and Adults. Chest 2024, 165, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajac, I.; Daines, C.; Durieu, I.; Goralski, J.L.; Heijerman, H.; Knoop, C.; Majoor, C.; Bruinsma, B.G.; Moskowitz, S.; Prieto-Centurion, V.; et al. Non-respiratory health-related quality of life in people with cystic fibrosis receiving elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, W.; Welsner, M.; Blosch, C.; Dillenhoefer, S.; Olivier, M.; Brinkmann, F.; Koerner-Rettberg, C.; Sutharsan, S.; Mellies, U.; Taube, C.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Health-Related Quality of Life and Short-Term Intervention with CFTR Modulator Therapy in Adults with Cystic Fibrosis: Evaluation of Changes over Several Years with or without 33 Weeks of CFTR Modulator Therapy. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Parameters | Points of Assessment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (0 Month) | 3 Months | 12 Months | Change Between 3 m and 0 | p * | Change Between 12 m and 0 | p * | ||||

| Mean ± sd | Min–Max | Mean ± sd | Min–Max | Mean ± sd | Min–Max | Mean ± sd | Mean ± sd | |||

| Age (years) | 14.19 ± 1.78 | 12–17 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||

| Body weight (kg) | 52.34 ± 11.64 | 32.3–90.3 | 55.66 ± 11.56 | 36.7–96.8 | 59.40 ± 11.96 | 39.40–106.3 | 3.33 ± 2.30 | <0.001 | 7.10 ± 4.62 | <0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) Female/Male | 49.82 ± 6.28/54.86 ± 14.89 | 52.87 ± 5.60/58.48 ± 14.94 | 55.56 ± 6.24/63.37 ± 14.67 | |||||||

| BMI-zscore | −0.30 ± 0.95 | −3.39–1.72 | 0.05 ± 0.82 | −2.33–1.83 | 0.18 ± 0.89 | −2.59–1.96 | 0.35 ± 0.36 | <0.001 | 0.47 ± 0.46 | <0.001 |

| BMI-zscore Female/Male | −0.08 ± 0.73/−0.51 ± 1.09 | 0.23 ± 0.60/−0.12 ± 0.96 | 0.29 ± 0.77/0.06 ± 1.02 | |||||||

| Fat mass (kg) | 10.88 ± 3.72 | 5.30–21.6 | 12.08 ± 4.19 | 5.10–25.7 | 13.64 ± 4.73 | 5.00–29.20 | 1.02 ± 2.09 | <0.001 | 2.70 ± 2.51 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (kg) Female/Male | 12.46 ± 2.90/9.3 ± 3.3 | 13.89 ± 3.15/10.4 ± 4.27 | 15.37 ± 3.69/11.85 ± 4.93 | |||||||

| FMI (kg/m2) | 4.02 ± 1.32 | 1.80–7.31 | 4.43 ± 1.54 | 1.89–8.33 | 4.90 ± 1.75 | 1.85–9.49 | 0.35 ± 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.86 ± 0.88 | <0.001 |

| FMI (kg/m2) Female/Male | 4.84 ± 1.06/3.22 ± 0.98 | 5.37 ± 1.24/3.57 ± 1.19 | 5.85 ± 1.50/3.91 ± 1.38 | |||||||

| Fat Free Mass (kg) | 41.47 ± 9.75 | 25–68.7 | 43.66 ± 9.66 | 28.6–71.10 | 45.76 ± 9.86 | 29.70–77.10 | 1.41 ± 5.52 | <0.001 | 4.40 ± 3.13 | <0.001 |

| Fat Free Mass (kg) Female/Male | 37.36 ± 3.96/45.49 ± 11.92 | 39.06 ± 3.21/47.99 ± 11.59 | 40.20 ± 3.48/51.51 ± 10.81 | |||||||

| FFMI (kg/m2) | 15.13 ± 1.92 | 11.41–20.51 | 15.77 ± 1.82 | 12.71–21.00 | 16.16 ± 1.99 | 12.85–22.28 | 0.36 ± 2.05 | <0.001 | 1.06 + 0.85 | <0.001 |

| FFMI (kg/m2) Female/Male | 14.52 ± 1.23/15.69 ± 2.27 | 15.07 ± 0.95/16.40 ± 2.16 | 15.26 ± 1.17/17.09 ± 2.21 | |||||||

| LCI2.5 | 9.52 ± 2.62 | 6.08–16.14 | 7.71 ± 1.91 | 6.08–14.88 | 7.81 ± 2.35 | 6.00–20.39 | −1.62 ± 2.15 | <0.001 | −1.68 ± 1.89 | <0.001 |

| LCI2.5 Female/Male | 8.96 ± 2.70/10.04 ± 2.45 | 7.78 ± 2.1/7.62 ± 1.66 | 7.77 ± 2.91/7.82 ± 1.61 | |||||||

| ppFEV1 (%) | 92.09 ± 17.67 | 38.00–134.0 | 100.91 ± 14.9 | 51.00–130.00 | 101.65 ± 14.92 | 50.00–136.00 | 8.91 ± 8.23 | <0.001 | 9.67 ± 8.77 | <0.001 |

| ppFEV1 (%) Female/Male | 95.39 ± 17.69/89.43 ± 16.8 | 101.52 ± 14.71/100.75 ± 14.95 | 102.89 ± 14.82/100.82 ± 14.6 | |||||||

| ppFEV1 ≥ 80% (n = 47) | 97.83 ± 12.11 | 81.00–134.00 | 105.53 ± 10.05 | 85.00–130.00 | 105.72 ± 11.23 | 77.00–136.00 | 7.70 ± 8.04 | <0.001 | 7.89 ± 7.95 | <0.001 |

| ppFEV1 < 80% (n = 10) | 65.10 ± 14.53 | 38.00–78.00 | 79.70 ± 16.78 | 51.00–99.00 | 83.10 ± 17.10 | 50.00–105.00 | 14.60 ± 6.91 | 0.004 | 18.00 ± 7.89 | 0.004 |

| ppFVC (%) | 98.31 ± 15.39 | 42.00–134.00 | 102.88 ± 13.29 | 48.00–131.00 | 103.00 ± 12.88 | 49.00–135.00 | 4.46 ± 5.24 | <0001 | 4.61 ± 5.70 | <0.001 |

| ppFVC (%) Female/Male | 100.11 ± 15.0/97.25 ± 15.11 | 104.07 ± 13.07/102.11 ± 13.27 | 104.86 ± 12.80/101.57 ± 12.47 | |||||||

| CFQ-R Respiratory | 81.71 ± 16.79 | 22.22–100.00 | 91.71 ± 11.43 | 50.00–100.00 | 93.85 ± 11.18 | 33.33–100.00 | 9.83 ± 16.48 ** | <0.001 | 11.75 ± 15.62 ** | <0.001 |

| CFQ-R Respiratory Female/Male | 83.13 ± 19.03/81.13 ± 12.55 | 93.01 ± 7.53/91.05 ± 13.93 | 94.72 ± 8.67/92.96 ± 13.16 | |||||||

| CFQ-R Eating | 83.65 ± 17.78 | 33.33–100.00 | 86.94 ± 15.16 | 33.33–100.00 | 91.22 ± 12.01 | 55.55–100.00 | 6.79 ± 22.58 | 0.088 | 7.90 ± 17.37 | 0.001 |

| CFQ-R Eating Female/Male | 81.75 ± 18.59/86.57 ± 16.03 | 85.44 ± 1.04/89.30 ± 11.90 | 92.06 ± 10.22/91.2 ± 12.72 | |||||||

| CFQ-R Physical | 88.23 ± 15.70 | 20.83–100.00 | 92.81 ± 11.01 | 58.33–100.00 | 96.32 ± 7.48 | 70.83–100.00 | 6.34 ± 17.78 | 0.003 | 7.74 ± 13.69 | <0.001 |

| CFQ-R Physical Female/Male | 85.3 ± 1.85/91.26 ± 11.87 | 91.6 ± 10.99/94.70 ± 10.24 | 94.34 ± 9.20/98.46 ± 4.24 | |||||||

| BMI (Percentiles) | Baseline (n) | 3 Months (n) | 12 Months (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50–85th | 26 | 32 | 27 |

| 25–49th | 12 | 10 | 11 |

| 24–10th | 13 | 9 | 5 |

| below 10th | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 85–94.9th | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| above 95th | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| ∆ of Parameters | ppFEV1 (%) * | ppFVC (%) * | LCI2.5 * | CFQ-R Respiratory * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 m vs. 0 m | 12 m vs. 0 m | 3 m vs. 0 m | 12 m vs. 0 m | 3 m vs. 0 m | 12 m vs. 0 m | 3 m vs. 0 m | 12 m vs. 0 m | |

| Body weight (kg) | 0.425 | 0.353 | 0.488 | 0.398 | - | - | 0.335 | - |

| BMI-zscore | 0.443 | 0.417 | 0.407 | 0.468 | −0.280 | −0.341 | 0.470 | 0.406 |

| Fat mass (kg) | - | - | 0.298 | 0.321 | - | - | - | - |

| FMI (kg/m2) | - | - | 0.290 | 0.292 | - | - | - | - |

| Fat Free Mass (kg) | 0.423 | 0.333 | 0.382 | 0.357 | - | - | 0.379 | - |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | 0.419 | 0.275 | 0.376 | 0.380 | - | - | 0.375 | - |

| CFQ-R Respiratory | 0.439 | 0.472 | 0.464 | 0.537 | −0.284 | - | n/a | n/a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walicka-Serzysko, K.; Postek, M.; Mielus, M.; Borawska-Kowalczyk, U.; Milczewska, J.; Zybert, K.; Wozniacki, Ł.; Wołkowicz, A.; Sands, D. Comprehensive Evaluation of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Paediatric Cystic Fibrosis: Nutritional, Pulmonary, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7969. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227969

Walicka-Serzysko K, Postek M, Mielus M, Borawska-Kowalczyk U, Milczewska J, Zybert K, Wozniacki Ł, Wołkowicz A, Sands D. Comprehensive Evaluation of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Paediatric Cystic Fibrosis: Nutritional, Pulmonary, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7969. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227969

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalicka-Serzysko, Katarzyna, Magdalena Postek, Monika Mielus, Urszula Borawska-Kowalczyk, Justyna Milczewska, Katarzyna Zybert, Łukasz Wozniacki, Anna Wołkowicz, and Dorota Sands. 2025. "Comprehensive Evaluation of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Paediatric Cystic Fibrosis: Nutritional, Pulmonary, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7969. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227969

APA StyleWalicka-Serzysko, K., Postek, M., Mielus, M., Borawska-Kowalczyk, U., Milczewska, J., Zybert, K., Wozniacki, Ł., Wołkowicz, A., & Sands, D. (2025). Comprehensive Evaluation of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Paediatric Cystic Fibrosis: Nutritional, Pulmonary, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7969. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227969