Waist Circumference as an Independent Marker of Insulin Resistance: Evidence from a Nationwide Korean Population Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Waist Circumference (WC)

2.3. Serum Insulin, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-β

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Association of WC with Insulin Resistance and Beta-Cell Function

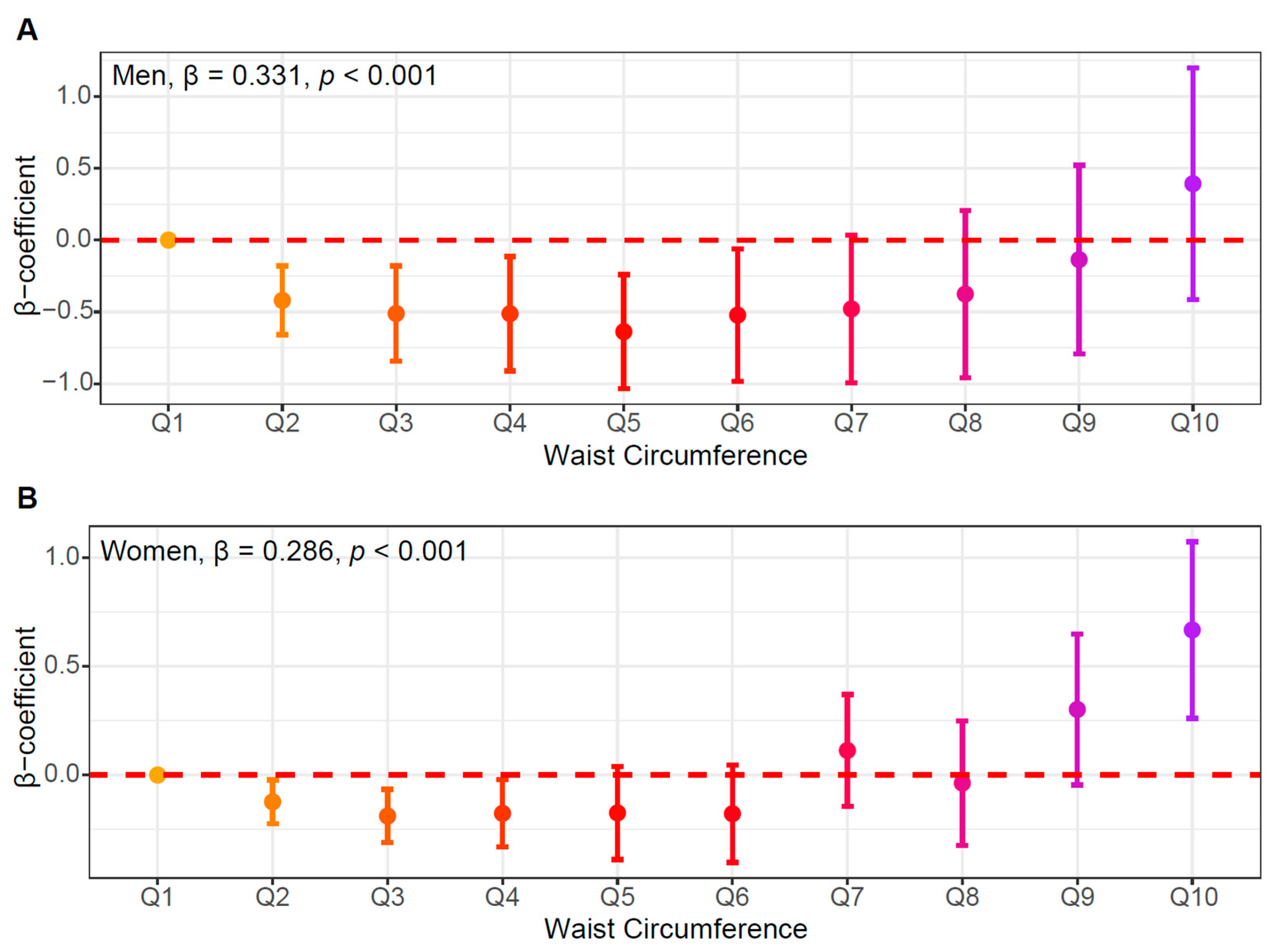

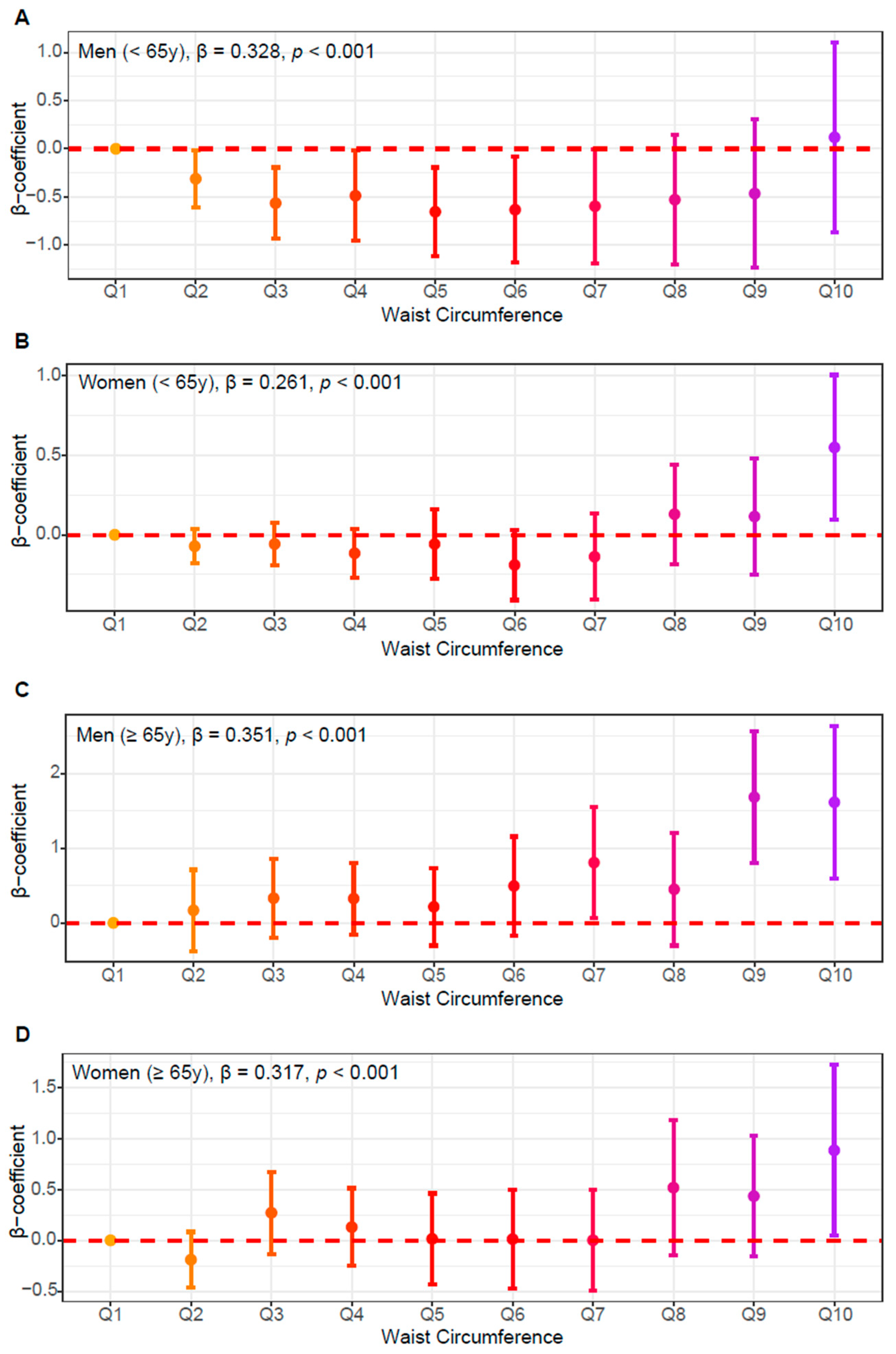

3.3. Independent Association of WC and HOMA-IR

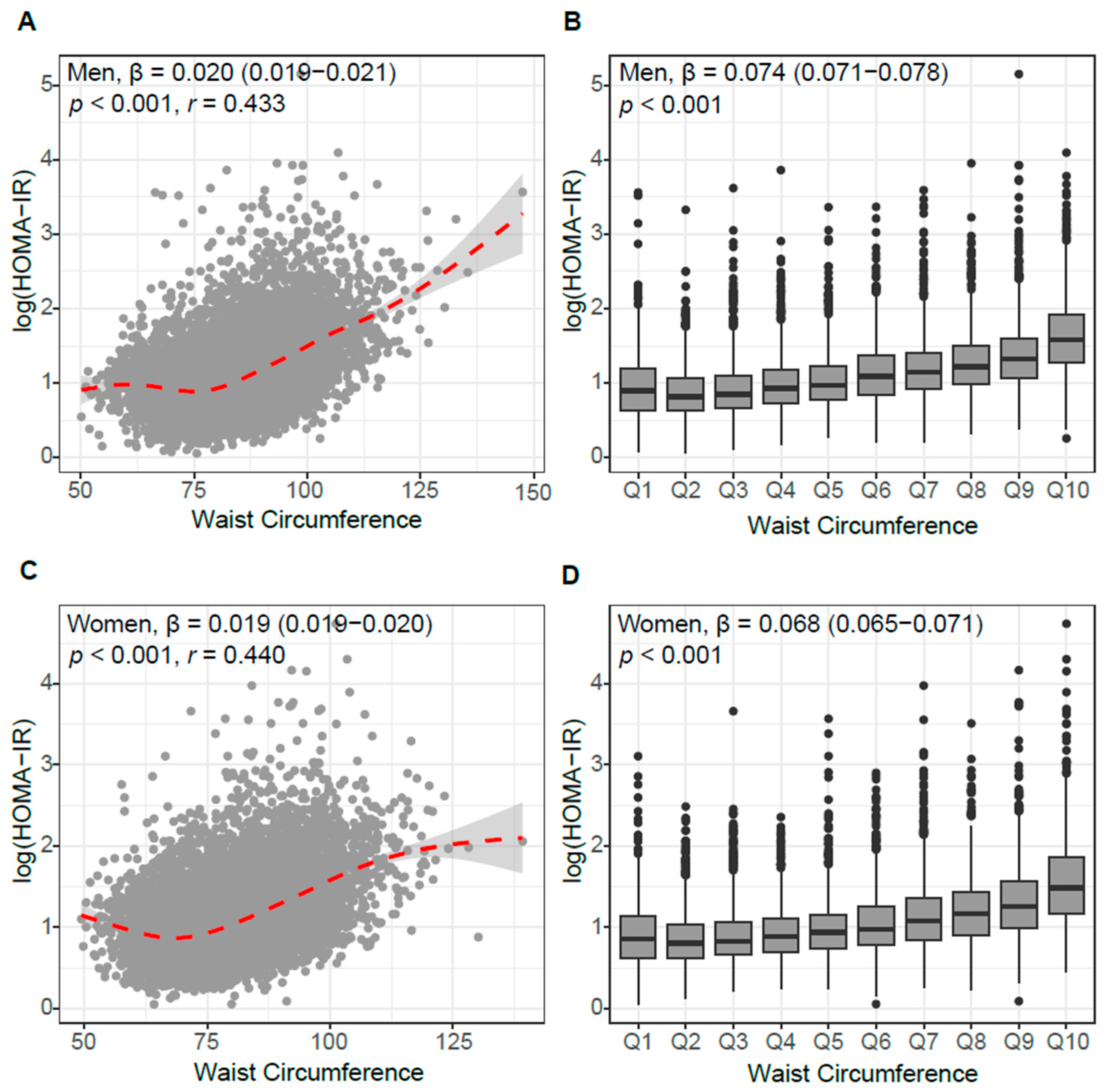

3.4. Linearity Between WC and Insulin Resistance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MetS | Metabolic syndrome |

| WC | Waist circumference |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| KNHANES | Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| KDCA | Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| HOMA-β | Homeostasis Model Assessment of β-cell function |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AHM | Antihypertensive medication |

| LLD | Lipid-lowering drug |

References

- Islam, M.S.; Wei, P.; Suzauddula, M.; Nime, I.; Feroz, F.; Acharjee, M.; Pan, F. The interplay of factors in metabolic syndrome: Understanding its roots and complexity. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.H.; Liu, Z.; Ho, S.C. Metabolic syndrome and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankoski, A.; Harris, T.B.; McClain, J.J.; Brychta, R.J.; Caserotti, P.; Chen, K.Y.; Berrigan, D.; Troiano, R.P.; Koster, A. Sedentary activity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of physical activity. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeidat, A.A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Ghabashi, M.A.; Alazzeh, A.Y.; Habib, S.M.; Abu Al-Haijaa, D.; Azzeh, F.S. Developmental Trends of Metabolic Syndrome in the Past Two Decades: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlani, Y.; Pothineni, N.V.; Kovelamudi, S.; Mehta, J.L. Metabolic syndrome: Pathophysiology, management, and modulation by natural compounds. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 11, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkau, B.; Charles, M.A. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet. Med. 1999, 16, 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. 1998, 15, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahrenberg, H.; Hertel, K.; Leijonhufvud, B.M.; Persson, L.G.; Toft, E.; Arner, P. Use of waist circumference to predict insulin resistance: Retrospective study. BMJ 2005, 330, 1363–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Executive summary. Cardiol. Rev. 2005, 13, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Manent, J.I.; Jover, A.M.; Martinez, C.S.; Tomás-Gil, P.; Martí-Lliteras, P.; López-González, Á.A. Waist Circumference Is an Essential Factor in Predicting Insulin Resistance and Early Detection of Metabolic Syndrome in Adults. Nutrients 2023, 15, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Kim, J.S.; Jo, M.J.; Cho, E.; Ahn, S.Y.; Kwon, Y.J.; Ko, G.J. The Roles and Associated Mechanisms of Adipokines in Development of Metabolic Syndrome. Molecules 2022, 27, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, M.I.; Kurylowicz, A.; Bartoszewicz, Z.; Lisik, W.; Jonas, M.; Domienik-Karlowicz, J.; Puzianowska-Kuznicka, M. Adiponectin/resistin interplay in serum and in adipose tissue of obese and normal-weight individuals. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2017, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Park, H.Y. Association between muscular strength, abdominal obesity, and incident nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a Korean population. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeland, I.J.; Ross, R.; Després, J.P.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Shai, I.; Seidell, J.; Magni, P.; Santos, R.D.; Arsenault, B.; et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: A position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, J. The Causal Role of Ectopic Fat Deposition in the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, S.A. Obesity, abdominal obesity, and insulin resistance. Clin. Cornerstone 2008, 9, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascaso, J.F.; Romero, P.; Real, J.T.; Lorente, R.I.; Martínez-Valls, J.; Carmena, R. Abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome in a southern European population. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2003, 14, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.Y.; Nam, G.E.; Han, K.; Hwang, H.S. Body weight variability and the risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A nationwide cohort study in Korea. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 190, 110015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Park, S.H.; Kang, Y.; Han, K.; Lee, S.H. Statin therapy in individuals with intermediate cardiovascular risk. Metabolism 2024, 150, 155723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigit, F.S.; Tahapary, D.L.; Trompet, S.; Sartono, E.; Willems van Dijk, K.; Rosendaal, F.R.; de Mutsert, R. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its association with body fat distribution in middle-aged individuals from Indonesia and the Netherlands: A cross-sectional analysis of two population-based studies. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakugi, H.; Ogihara, T. The metabolic syndrome in the asian population. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2005, 7, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.R.; Lim, S. Clinical characteristics of metabolic syndrome in Korea, and its comparison with other Asian countries. J. Diabetes Investig. 2015, 6, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, K.; Tojjar, D.; Yamada, S.; Toda, K.; Patel, C.J.; Butte, A.J. Ethnic differences in the relationship between insulin sensitivity and insulin response: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haam, J.H.; Kim, B.T.; Kim, E.M.; Kwon, H.; Kang, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.K.; Rhee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, K.Y. Diagnosis of Obesity: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 32, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Oh, S.W. Optimal waist circumference cutoff values for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity in korean adults. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 29, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Neeland, I.J.; Yamashita, S.; Shai, I.; Seidell, J.; Magni, P.; Santos, R.D.; Arsenault, B.; Cuevas, A.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: A Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakelides, H.; Irving, B.A.; Short, K.R.; O’Brien, P.; Nair, K.S. Age, obesity, and sex effects on insulin sensitivity and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Diabetes 2010, 59, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.M.; Weschenfelder, J.; Sander, C.; Minkwitz, J.; Thormann, J.; Chittka, T.; Mergl, R.; Kirkby, K.C.; Faßhauer, M.; Stumvoll, M.; et al. Inflammatory cytokines in general and central obesity and modulating effects of physical activity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, D.G.; Jenkins, A.B.; Campbell, L.V.; Freund, J.; Chisholm, D.J. Abdominal fat and insulin resistance in normal and overweight women: Direct measurements reveal a strong relationship in subjects at both low and high risk of NIDDM. Diabetes 1996, 45, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedland, E.S. Role of a critical visceral adipose tissue threshold (CVATT) in metabolic syndrome: Implications for controlling dietary carbohydrates: A review. Nutr. Metab. 2004, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.P.; Prado, C.M.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Shepherd, J.A. Evaluation of visceral adipose tissue thresholds for elevated metabolic syndrome risk across diverse populations: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, J.; Chen, P.J.; Xiao, W.H. Mechanism of increased risk of insulin resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seko, T.; Akasaka, H.; Koyama, M.; Himuro, N.; Saitoh, S.; Miura, T.; Mori, M.; Ohnishi, H. Preserved Lower Limb Muscle Mass Prevents Insulin Resistance Development in Nondiabetic Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 376–381.e371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yue, R. Aging adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Biogerontology 2024, 25, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.J.; Liang, L.J.; Lee, C.C. Associations of appendicular lean mass and abdominal adiposity with insulin resistance in older adults: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerlander, A.A.; Lyass, A.; Mahoney, T.F.; Massaro, J.M.; Long, M.T.; Vasan, R.S.; Hoffmann, U. Sex Differences in the Associations of Visceral Adipose Tissue and Cardiometabolic and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elffers, T.W.; de Mutsert, R.; Lamb, H.J.; de Roos, A.; Willems van Dijk, K.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Jukema, J.W.; Trompet, S. Body fat distribution, in particular visceral fat, is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in obese women. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.L.; Schulkin, J. Sex differences in fat storage, fat metabolism, and the health risks from obesity: Possible evolutionary origins. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, B.; Shu, J. Role of estrogen in the regulation of central and peripheral energy homeostasis: From a menopausal perspective. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 14, 20420188231199359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.S.; Xie, W.; Johnson, W.D.; Cefalu, W.T.; Redman, L.M.; Ravussin, E. Defining insulin resistance from hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Men | Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WC, cm (n) | Total (8886) | <90 (5662) | 90–102 (2689) | >102 (535) | p for Trend | Total (11,316) | <85 (7865) | 85–95 (2511) | >95 (940) | p for Trend |

| Age, y | 47.9 ± 20.40 | 45 ± 21.26 | 53.9 ± 17.31 | 48.9 ± 18.86 | <0.001 | 49.8 ± 19.03 | 45.6 ± 18.85 | 59.8 ± 15.20 | 59.3 ± 16.34 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.3 ± 3.63 | 22.4 ± 2.54 | 26.7 ± 2.04 | 31.6 ± 3.34 | <0.001 | 23.4 ± 3.77 | 21.7 ± 2.45 | 26.1 ± 2.14 | 30.6 ± 3.54 | <0.001 |

| WC, cm | 86.4 ± 10.52 | 80.4 ± 7.37 | 94.8 ± 3.28 | 107.6 ± 5.69 | <0.001 | 79.9 ± 10.53 | 74.5 ± 6.67 | 89.2 ± 2.74 | 100.7 ± 5.57 | <0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 120.4 ± 14.85 | 118 ± 14.83 | 124.5 ± 14.1 | 125.7 ± 12.72 | <0.001 | 117 ± 17.55 | 113.4 ± 16.55 | 124.4 ± 17.33 | 127.6 ± 15.6 | <0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 75.7 ± 10.53 | 73.9 ± 10.16 | 78.5 ± 10.26 | 80.1 ± 11.40 | <0.001 | 72.8 ± 9.51 | 71.7 ± 9.32 | 75 ± 9.41 | 76.7 ± 9.41 | <0.001 |

| AHM, n | 1921 (21.6) | 838 (14.8) | 884 (32.9) | 199 (37.2) | <0.001 | 2463 (21.8) | 1029 (13.1) | 968 (38.6) | 466 (49.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n | 928 (10.4) | 424 (7.5) | 399 (14.8) | 105 (19.6) | <0.001 | 989 (8.7) | 389 (4.9) | 398 (15.9) | 202 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| LLD, n | 1019 (11.5) | 463 (8.2) | 446 (16.6) | 110 (20.6) | <0.001 | 1834 (16.2) | 835 (10.6) | 703 (28) | 296 (31.5) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | 2413 (27.2) | 1473 (26) | 793 (29.5) | 147 (27.5) | 0.004 | 504 (4.5) | 323 (4.1) | 119 (4.7) | 62 (6.6) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1999 (22.5) | 1116 (19.7) | 745 (27.7) | 138 (25.8) | <0.001 | 917 (8.1) | 653 (8.3) | 187 (7.4) | 77 (8.2) | 0.39 |

| Physical activity | 1807 (20.3) | 1249 (22.1) | 474 (17.6) | 84 (15.7) | <0.001 | 1743 (15.4) | 1387 (17.6) | 267 (10.6) | 89 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Men | Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WC, cm (n) | Total (8886) | <90 (5662) | 90–102 (2689) | >102 (535) | p for Trend | Total (11,316) | <85 (7865) | 85–95 (2511) | >95 (940) | p for Trend |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 48.1 ± 11.43 | 50 ± 11.63 | 45.1 ± 10.33 | 42.8 ± 9.44 | <0.001 | 54.8 ± 12.72 | 56.8 ± 12.75 | 50.8 ± 11.64 | 49.1 ± 10.87 | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C, mg/dL | 136.2 ± 38.31 | 132.1 ± 37.11 | 143.1 ± 39.09 | 144.8 ± 40.46 | <0.001 | 135.5 ± 36.74 | 133 ± 35.22 | 141.1 ± 38.59 | 141.2 ± 41.51 | <0.001 |

| TG, mg/dL | 144.6 ± 119.41 | 126.1 ± 107.78 | 175.6 ± 131.79 | 183.5 ± 129.27 | <0.001 | 111.1 ± 70.29 | 99.1 ± 62.62 | 134.4 ± 76.55 | 148.4 ± 83.53 | <0.001 |

| Insulin, μU/mL | 10.1 ± 10.20 | 8.1 ± 7.01 | 12.3 ± 12.53 | 20 ± 15.87 | <0.001 | 9.3 ± 8.43 | 7.8 ± 6.36 | 11.2 ± 8.17 | 16.9 ± 15.86 | <0.001 |

| Glc, mg/dL | 103.3 ± 24.16 | 99.8 ± 20.73 | 108.3 ± 26.65 | 115.4 ± 34.27 | <0.001 | 99.2 ± 21.65 | 95.3 ± 17.1 | 106 ± 25.87 | 112.8 ± 31.22 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.7 ± 3.49 | 2 ± 2.09 | 3.4 ± 4.68 | 5.8 ± 5.4 | <0.001 | 2.4 ± 2.89 | 1.9 ± 1.77 | 3.1 ± 3.08 | 5 ± 6.24 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-β | 101.4 ± 99.73 | 89 ± 82.93 | 112.7 ± 100.24 | 175.8 ± 184.86 | <0.001 | 101.8 ± 95.5 | 94.7 ± 73.28 | 108.6 ± 133.2 | 143 ± 123.49 | <0.001 |

| Men | Women | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | se | 95% CI | t | p | R2 | β | se | 95% CI | t | p | R2 | |

| Model 1 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.024–0.026 | 45.2 | <0.001 | 0.269 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.024–0.026 | 47.8 | <0.001 | 0.264 |

| Model 2 | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.023–0.025 | 42.9 | <0.001 | 0.296 | 0.023 | 0.001 | 0.022–0.024 | 45.2 | <0.001 | 0.305 |

| Model 3 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.014–0.02 | 12.4 | <0.001 | 0.320 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.013–0.017 | 13.8 | <0.001 | 0.331 |

| Model 4 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.011–0.016 | 11.5 | <0.001 | 0.465 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.008–0.011 | 10.2 | <0.001 | 0.497 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, S.H.; Lee, T.; Oh, J.; Hwang, K.-H.; Choi, E.H.; Cha, S.-K. Waist Circumference as an Independent Marker of Insulin Resistance: Evidence from a Nationwide Korean Population Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7957. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227957

Lim SH, Lee T, Oh J, Hwang K-H, Choi EH, Cha S-K. Waist Circumference as an Independent Marker of Insulin Resistance: Evidence from a Nationwide Korean Population Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7957. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227957

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Sung Ha, Taesic Lee, Jiyeon Oh, Kyu-Hee Hwang, Eung Ho Choi, and Seung-Kuy Cha. 2025. "Waist Circumference as an Independent Marker of Insulin Resistance: Evidence from a Nationwide Korean Population Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7957. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227957

APA StyleLim, S. H., Lee, T., Oh, J., Hwang, K.-H., Choi, E. H., & Cha, S.-K. (2025). Waist Circumference as an Independent Marker of Insulin Resistance: Evidence from a Nationwide Korean Population Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7957. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227957