Chondroblastic Subtype Is Associated with Higher Rates of Local Recurrence in Skeletal Osteosarcoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Data Collection

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Tumor Characteristics and Surgical Interventions

3.3. Chemotherapy Delivery

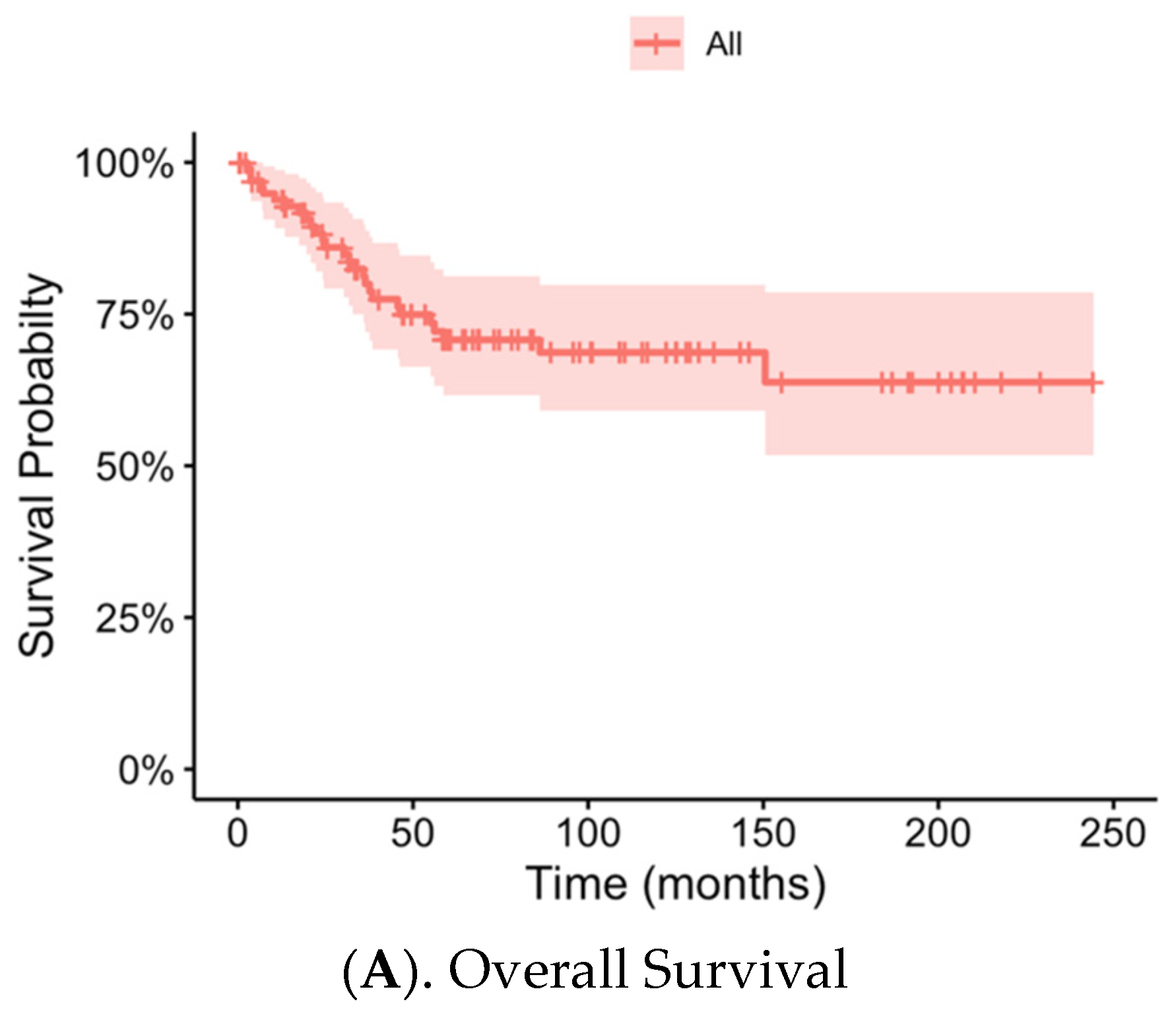

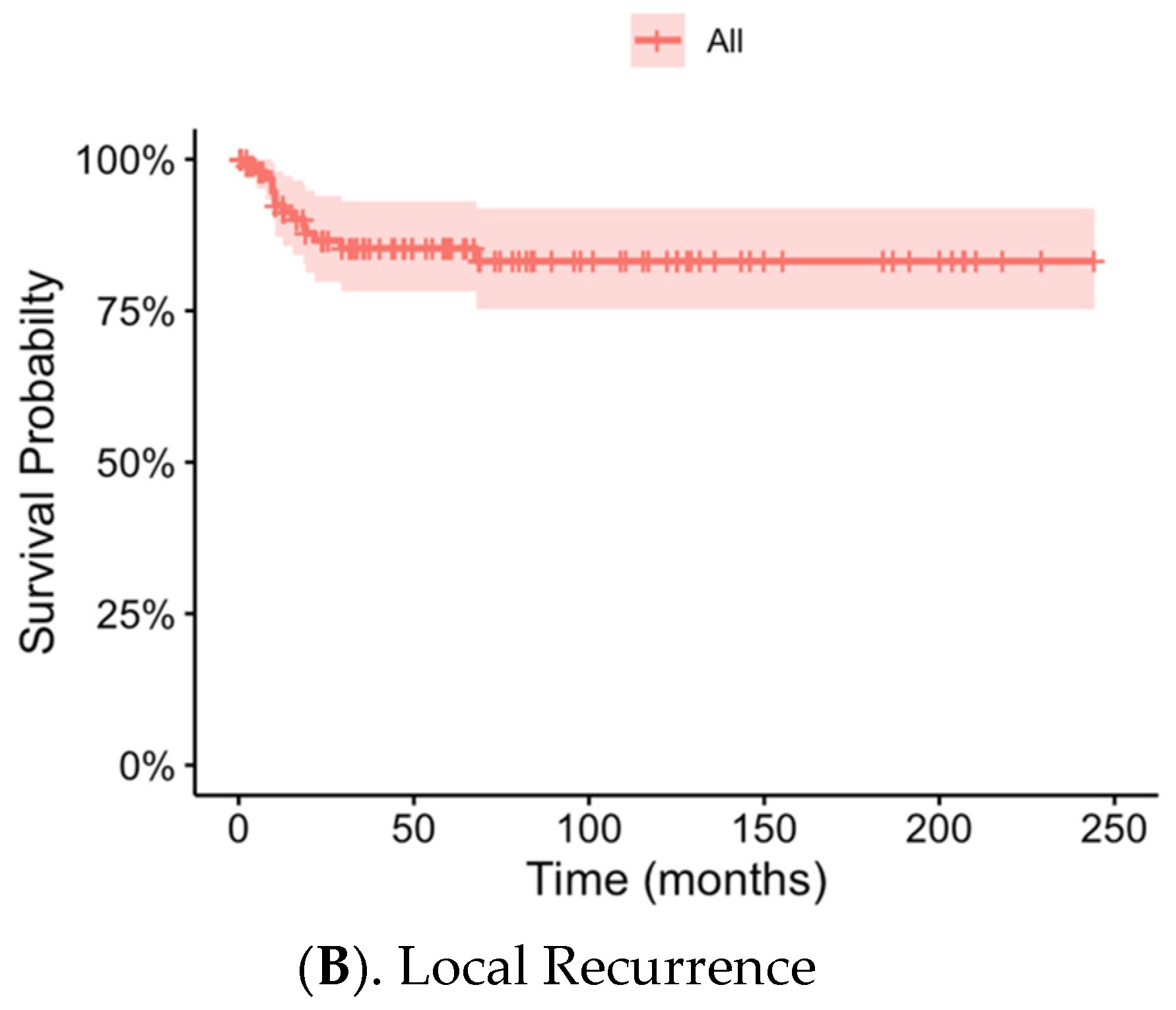

3.4. Local Recurrence, Metastasis and Overall Patient Survival

3.5. Risk Factors for Local Recurrence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| LR | Local recurrence |

| n | Number |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| OSH | Outside Hospital |

References

- Mirabello, L.; Troisi, R.J.; Savage, S.A. International Osteosarcoma Incidence Patterns in Children and Adolescents, Middle Ages and Elderly Persons. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.J.; Leung, D.; Heslin, M.; Woodruff, J.M.; Brennan, M.F. Association of Local Recurrence with Subsequent Survival in Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacci, G.; Longhi, A.; Cesari, M.; Versari, M.; Bertoni, F. Influence of Local Recurrence on Survival in Patients with Extremity Osteosarcoma Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: The Experience of a Single Institution with 44 Patients. Cancer 2006, 106, 2701–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeden, S.; Grimer, R.J.; Cannon, S.R.; Taminiau, A.H.; Uscinska, B.M.; Intergroup European Osteosarcoma. The Effect of Local Recurrence on Survival in Resected Osteosarcoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Lewis, V.O.; Satcher, R.L.; Moon, B.S.; Lin, P.P. What Are the Factors That Affect Survival and Relapse after Local Recurrence of Osteosarcoma? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014, 472, 3188–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Shah, N.; McCarville, M.B.; Billups, C.A.; Neel, M.N.; Rao, B.N.; Daw, N.C. Outcome after Local Recurrence of Osteosarcoma: The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Experience (1970–2000). Cancer 2004, 100, 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, T.E.; Cruz, A.; Binitie, O.; Cheong, D.; Letson, G.D. Do Surgical Margins Affect Local Recurrence and Survival in Extremity, Nonmetastatic, High-Grade Osteosarcoma? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2016, 474, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S.S.; Gorlick, R.; Bukata, S.; Chou, A.; Morris, C.D.; Boland, P.J.; Huvos, A.G.; Meyers, P.A.; Healey, J.H. Treatment Algorithm for Locally Recurrent Osteosarcoma Based on Local Disease-Free Interval and the Presence of Lung Metastasis. Cancer 2006, 107, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Y.; Yu, P.; Bao, Q.; Wen, J.; Hu, C.; Qiu, S. Effects of Resection Margins on Local Recurrence of Osteosarcoma in Extremity and Pelvis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2016, 36, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.H.; Navid, F.; Wang, C.; Bahrami, A.; Wu, J.; Neel, M.D.; Rao, B.N. Management of Local Recurrence of Pediatric Osteosarcoma Following Limb-Sparing Surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 1948–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, D.; Bielack, S.S.; Carrle, D.; Kevric, M.; Kotz, R.; Winkelmann, W.; Jundt, G.; Werner, M.; Fehlberg, S.; Kager, L.; et al. The Influence of Tumor- and Treatment-Related Factors on the Development of Local Recurrence in Osteosarcoma after Adequate Surgery. An Analysis of 1355 Patients Treated on Neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group Protocols. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Sugita, T.; Sato, K.; Hotta, T.; Tsuchiya, H.; Shimose, S.; Kubo, T.; Ochi, M. Clinical Outcomes of 54 Pelvic Osteosarcomas Registered by Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group. Oncology 2005, 68, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Stamatopoulos, A.; Athanasiadis, D.I.; Kenanidis, E.; Potoupnis, M.; Haidich, A.B.; Tsiridis, E. Limb-Salvage Surgery Offers Better Five-Year Survival Rate Than Amputation in Patients with Limb Osteosarcoma Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Bone Oncol. 2020, 25, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, R.R.; Tiwari, V.; Kumar, V.S.; Bakhshi, S.; Gamanagatti, S.; Khan, S.A.; Rastogi, S. Factors Associated with Local Recurrence in Operated Osteosarcomas: A Retrospective Evaluation of 95 Cases from a Tertiary Care Center in a Resource Challenged Environment. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 115, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, G.; Forni, C.; Longhi, A.; Ferrari, S.; Mercuri, M.; Bertoni, F.; Serra, M.; Briccoli, A.; Balladelli, A.; Picci, P. Local Recurrence and Local Control of Non-Metastatic Osteosarcoma of the Extremities: A 27-Year Experience in a Single Institution. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 96, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, D.; Giacomini, S.; Gozzi, E.; Ferrari, S.; Sangiorgi, L.; Tienghi, A.; DeGroot, H.; Bertoni, F.; Bacchini, P.; Bacci, G.; et al. Osteosarcoma of the Pelvis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2004, 30, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosjo, O. Surgical Procedure and Local Recurrence in 223 Patients Treated 1982–1997 According to Two Osteosarcoma Chemotherapy Protocols. The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Experience. Acta. Orthop. Scand. 1999, 70 (Suppl. S285), 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Cui, J.Q.; Zhou, Z.M.; Guo, K.J. Prognostic Factors to Survival of Patients with Chondroblastic Osteosarcoma. Medicine 2018, 97, e12636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, G.; Ferrari, S.; Mercuri, M.; Bertoni, F.; Picci, P.; Manfrini, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Forni, C.; Cesari, M.; Campanacci, M. Predictive Factors for Local Recurrence in Osteosarcoma: 540 Patients with Extremity Tumors Followed for Minimum 2.5 Years after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1998, 69, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielack, S.S.; Kempf-Bielack, B.; Delling, G.; Exner, G.U.; Flege, S.; Helmke, K.; Kotz, R.; Salzer-Kuntschik, M.; Werner, M.; Winkelmann, W.; et al. Prognostic Factors in High-Grade Osteosarcoma of the Extremities or Trunk: An Analysis of 1702 Patients Treated on Neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group Protocols. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, A.T.; de Abreu Alves, F.; Pinto, C.A.; Carvalho, A.L.; Kowalski, L.P.; Lopes, M.A. Clinicopathological and Immunohistochemical Analysis of Twenty-Five Head and Neck Osteosarcomas. Oral. Oncol. 2003, 39, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacci, G.; Bertoni, F.; Longhi, A.; Ferrari, S.; Forni, C.; Biagini, R.; Bacchini, P.; Donati, D.; Manfrini, M.; Bernini, G.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for High-Grade Central Osteosarcoma of the Extremity. Histologic Response to Preoperative Chemotherapy Correlates with Histologic Subtype of the Tumor. Cancer 2003, 97, 3068–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yu, S. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Insights into Chemotherapy-Induced Remodeling of the Osteosarcoma Tumor Microenvironment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Bacci, G.; Picci, P.; Mercuri, M.; Briccoli, A.; Pinto, D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Tienghi, A.; del Prever, A.B. Long-Term Follow-up and Post-Relapse Survival in Patients with Non-Metastatic Osteosarcoma of the Extremity Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 1997, 8, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wippel, B.; Gundle, K.R.; Dang, T.; Paxton, J.; Bubalo, J.; Stork, L.; Fu, R.; Ryan, C.W.; Davis, L.E. Safety and Efficacy of High-Dose Methotrexate for Osteosarcoma in Adolescents Compared with Young Adults. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delepine, N.; Delepine, G.; Bacci, G.; Rosen, G.; Desbois, J.C. Influence of Methotrexate Dose Intensity on Outcome of Patients with High Grade Osteogenic Osteosarcoma. Analysis of the Literature. Cancer 1996, 78, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, F.; Voigtlander, H.; Jang, H.; Schlemmer, H.P.; Kauczor, H.U.; Sedaghat, S. Predicting the Malignancy Grade of Soft Tissue Sarcomas on Mri Using Conventional Image Reading and Radiomics. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 102) | No LR (n = 88) | LR (n = 14) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean ([min-max]; SD) | 25.6 ([4–84]; 16.9) | 24.7 ([4–84]; 16.5) | 31.3 ([12–67]; 18.9) | 0.24 |

| BMI (kg/m2), Mean (SD) | 25.2 (8.4) | 25.0 (8.3) | 26.8 (8.8) | 0.54 |

| Sex, n (%) | >0.99 | |||

| Female | 46 (45.1%) | 40 (45.5%) | 6 (42.9%) | |

| Male | 56 (54.9%) | 48 (54.5%) | 8 (57.1%) | |

| History of Tobacco Use, n (%) | 22 (21.6%) | 17 (19.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.18 |

| Total (n = 102) | No LR (n = 88) | LR (n = 14) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Size, Mean (SD) | 11.0 (5.2) | 11.1 (5.37) | 10.5 (4.1) | 0.65 |

| Tumor Grade, n (%) | 0.75 | |||

| 1 | 8 (7.8%) | 8 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 2 | 13 (12.7%) | 11 (12.5%) | 2 (14.3%) | |

| 3 | 73 (71.6%) | 62 (70.5%) | 11 (78.6%) | |

| Pelvic Location, n (%) | 4 (3.9%) | 2 (2.3%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.09 |

| Biopsy at OSH, n (%) | 15 (14.7%) | 13 (14.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | >0.99 |

| Amputation, n (%) | 10 (9.8%) | 9 (10.2%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.69 |

| Chondroblastic Osteosarcoma, n (%) | 25 (24.5%) | 17 (19.3%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0.005 |

| Positive Surgical Margin, n (%) | 12 (11.8%) | 9 (10.2%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0.37 |

| Surgical Margin < 0.1 cm * | 14 (13.7%) | 13 (14.8%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.68 |

| Surgical Margin < 1.0 cm * | 61 (59.8%) | 51 (58.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | 0.68 |

| Surgical Margin > 2 cm * | 9 (8.8%) | 8 (9.1%) | 1 (7.1%) | >0.99 |

| Surgery at OSH, n (%) | 13 (12.7%) | 11 (12.5%) | 2 (14.3%) | >0.99 |

| Total (n = 80) | No LR (n = 69) | LR (n = 11) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant, (n, %) | 69 (86.3%) | 60 (87.0%) | 9 (81.8%) | 0.43 |

| Treatment Response, (n, %) | 0.25 | |||

| <50% | 10 (12.5%) | 8 (11.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0.60 |

| [50%, 75%) | 15 (18.8%) | 14 (20.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0.19 |

| [75%, 90%) | 8 (10.0%) | 7 (10.1%) | 1 (9.1%) | >0.99 |

| ≥90% | 34 (42.5%) | 27 (39.1%) | 7 (63.6%) | 0.48 |

| Doxorubicin, (n, %) | 74 (92.5%) | 64 (92.8%) | 10 (90.9%) | >0.99 |

| Doxorubicin Cumulative Dose (mg/m2), Mean (SD) | 397.6 (98.8) | 403.7 (91.7) | 360.9 (135.9) | 0.28 |

| Cisplatin, (n, %) | 74 (92.5%) | 64 (92.8%) | 10 (90.9%) | >0.99 |

| Cisplatin Cumulative Dose (mg/m2), Mean (SD) | 461.6 (112.6) | 471.2 (107.0) | 411.3 (135.2) | 0.19 |

| Methotrexate, (n, %) | 60 (75.0%) | 51 (73.9%) | 9 (81.8%) | 0.68 |

| Number of Cycles of Methotrexate, Mean (SD) | 8.5 (3.8) | 9.1 (3.7) | 6.7 (4.7) | 0.092 |

| Ifosfamide, (n, %) | 16 (20%) | 14 (20.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | >0.99 |

| Etoposide, (n, %) | 14 (17.5%) | 12 (17.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | >0.99 |

| Treatment Disruption/Delay, (n, %) | 51 (63.8%) | 44 (63.8%) | 7 (63.6%) | >0.99 |

| Duration to Start of Postoperative Chemotherapy, (n, %), Days | ||||

| <14 days | 5 (6.3%) | 5 (7.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.99 |

| [14, 28 days) | 30 (37.5%) | 26 (37.7%) | 4 (36.6%) | 0.71 |

| ≥28 days | 24 (30.3%) | 20 (29.0.%) | 4 (36.6%) | 0.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krez, A.N.; Fagan-Kellogg, S.; Graves, L.A.; Mebrahtu, A.; Levine, N.L.; Sachs, E.; Eward, W.C.; Brigman, B.E.; Visgauss, J.D. Chondroblastic Subtype Is Associated with Higher Rates of Local Recurrence in Skeletal Osteosarcoma. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227952

Krez AN, Fagan-Kellogg S, Graves LA, Mebrahtu A, Levine NL, Sachs E, Eward WC, Brigman BE, Visgauss JD. Chondroblastic Subtype Is Associated with Higher Rates of Local Recurrence in Skeletal Osteosarcoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227952

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrez, Alexandra N., Sarah Fagan-Kellogg, Laurie A. Graves, Aron Mebrahtu, Nicole L. Levine, Elizabeth Sachs, William C. Eward, Brian E. Brigman, and Julia D. Visgauss. 2025. "Chondroblastic Subtype Is Associated with Higher Rates of Local Recurrence in Skeletal Osteosarcoma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227952

APA StyleKrez, A. N., Fagan-Kellogg, S., Graves, L. A., Mebrahtu, A., Levine, N. L., Sachs, E., Eward, W. C., Brigman, B. E., & Visgauss, J. D. (2025). Chondroblastic Subtype Is Associated with Higher Rates of Local Recurrence in Skeletal Osteosarcoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227952