Accuracy of Emergency Physician-Performed Echocardiography for Diastolic Dysfunction in Suspected Acute Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

2.3. Screening and Assessment of Studies

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Data Synthesis

3. Results

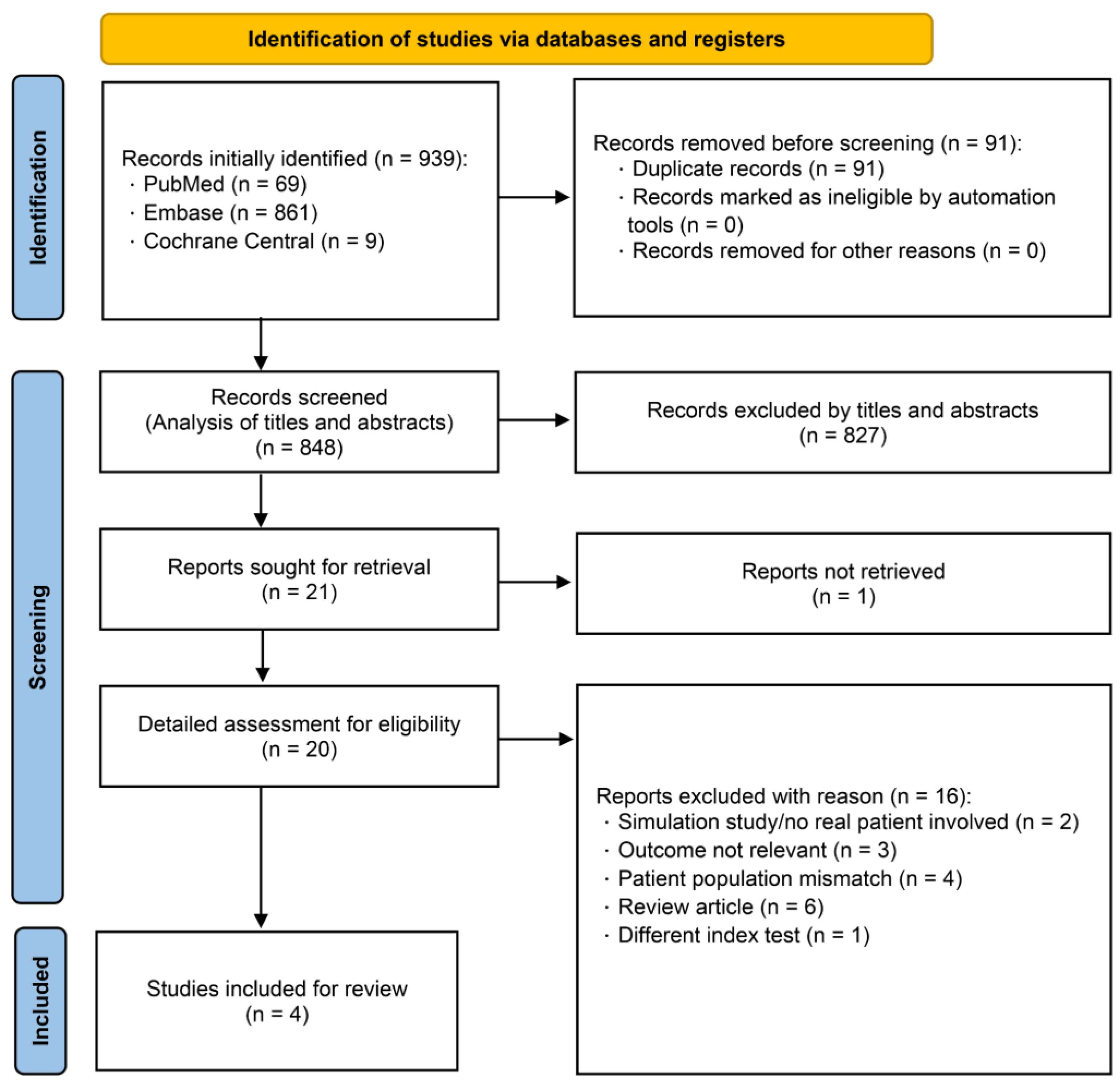

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Description of Included Studies

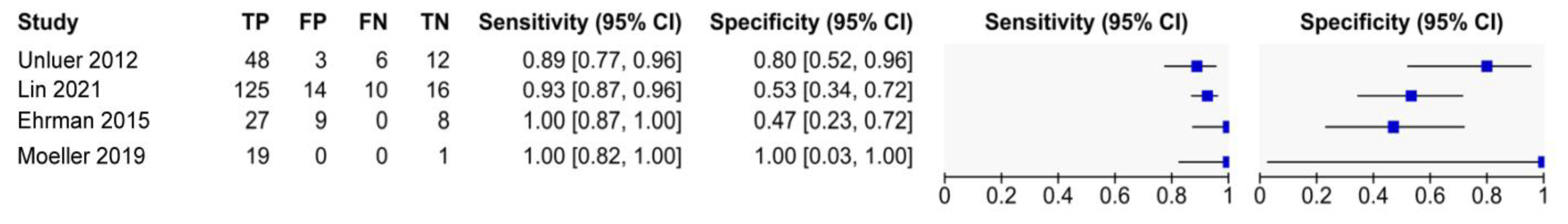

3.3. Overall Diagnostic Values of EP-FCU for Diastolic Dysfunction

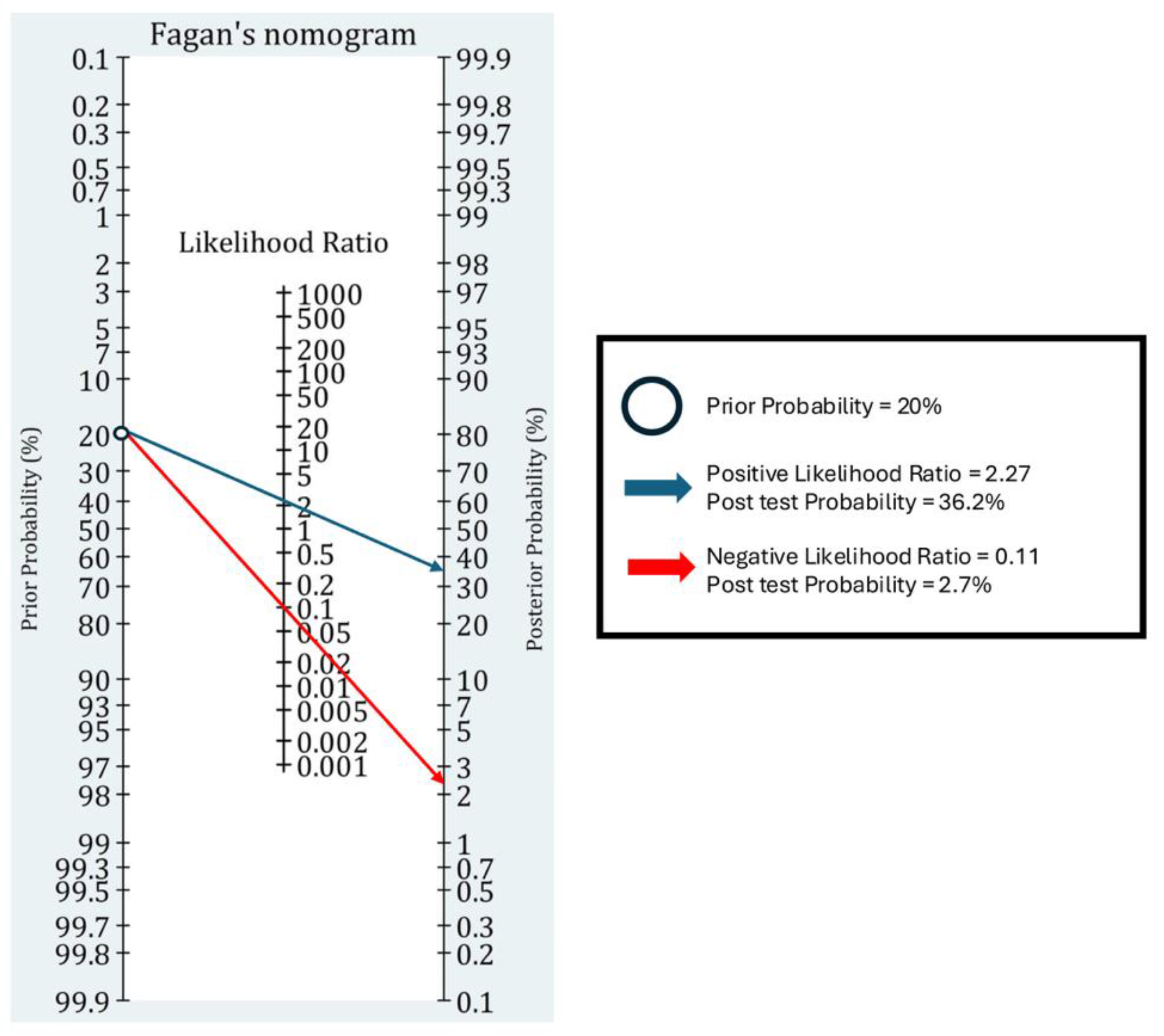

3.4. Clinical Utility of EP-FCU to Diagnose Diastolic Dysfunction

3.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Integration with International Guidelines

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABEM | American Board of Emergency Medicine |

| ACEP | American College of Emergency Physicians |

| AEMUS | Advanced Emergency Medicine Ultrasonography |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ASE | American Society of Echocardiography |

| CENTRAL | Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DD | Diastolic Dysfunction |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| EF | Ejection Fraction |

| EACVI | European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging |

| EP | Emergency Physician |

| EP-FCU | Emergency Physician-performed Focused Cardiac Ultrasound |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FCU | Focused Cardiac Ultrasound |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| HFpEF | Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction |

| HSROC | Hierarchical Summary Receiver-Operating Characteristic |

| LA | Left Atrium |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| NLR | Negative Likelihood Ratio |

| PLR | Positive Likelihood Ratio |

| PRISMA-DTA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Diagnostic Test Accuracy |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies—2 |

| Rayyan | Web-based screening tool for systematic reviews |

| RevMan | Review Manager |

| TDI | Tissue Doppler Imaging |

| TR | Tricuspid Regurgitation |

| TTE | Transthoracic Echocardiography |

References

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Shah, A.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Perspective. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1598–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschope, C.; de Boer, R.A.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: A consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e895–e1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Sanborn, D.Y.; Oh, J.K.; Anderson, B.; Billick, K.; Derumeaux, G.; Klein, A.; Koulogiannis, K.; Mitchell, C.; Shah, A.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography and for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Diagnosis: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2025, 38, 537–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F., 3rd; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omote, K.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riet, E.E.; Hoes, A.W.; Limburg, A.; Landman, M.A.; van der Hoeven, H.; Rutten, F.H. Prevalence of unrecognized heart failure in older persons with shortness of breath on exertion. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via, G.; Tavazzi, G. Diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction in the emergency department: Really at reach for minimally trained sonologists? A call for a wise approach to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction diagnosis in the ER. Crit. Ultrasound J. 2018, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unluer, E.E.; Bayata, S.; Postaci, N.; Yesil, M.; Yavasi, O.; Kara, P.H.; Vandenberk, N.; Akay, S. Limited bedside echocardiography by emergency physicians for diagnosis of diastolic heart failure. Emerg. Med. J. 2012, 29, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrman, R.R.; Russell, F.M.; Ansari, A.H.; Margeta, B.; Clary, J.M.; Christian, E.; Cosby, K.S.; Bailitz, J. Can emergency physicians diagnose and correctly classify diastolic dysfunction using bedside echocardiography? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 33, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Drapkin, J.; Likourezos, A.; Giakoumatos, E.; Schachter, M.; Sarkis, J.P.; Shetty, V.; Moskovits, M.; Haines, L.; Dickman, E. Emergency physician bedside echocardiographic identification of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 44, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arques, S.; Quennelle, F.; Roux, E. Accuracy of peak mitral e-wave velocity in the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in older patients with acute dyspnea. Ann. Cardiol. Angeiol. 2021, 70, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.M.; Franci, D.; Schweller, M.; Ribeiro, D.L.; Gontijo-Coutinho, C.M.; Matos-Souza, J.R.; de Carvalho-Filho, M.A. Left Ventricle Tissue Doppler Imaging Predicts Disease Severity in Septic Patients Newly Admitted in an Emergency Unit. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 49, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labovitz, A.J.; Noble, V.E.; Bierig, M.; Goldstein, S.A.; Jones, R.; Kort, S.; Porter, T.R.; Spencer, K.T.; Tayal, V.S.; Wei, K. Focused cardiac ultrasound in the emergent setting: A consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and American College of Emergency Physicians. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neskovic, A.N.; Hagendorff, A.; Lancellotti, P.; Guarracino, F.; Varga, A.; Cosyns, B.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Popescu, B.A.; Gargani, L.; Zamorano, J.L.; et al. Emergency echocardiography: The European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging recommendations. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Leo, M.; Liu, R.; Johnston, M.; Keehbauch, J.; Barton, M.; Kendall, J. The 2023 Core Content of advanced emergency medicine ultrasonography. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2023, 4, e13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Deeks, J.J.; Leeflang, M.M.; Takwoingi, Y.; Flemyng, E. Evaluating medical tests: Introducing the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 7, ED000163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; McInnes, M.D.F. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Diagnostic Test Accuracy: The PRISMA-DTA Statement. Radiology 2018, 289, 313–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, R.M.; Whiting, P. Metandi: Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy Using Hierarchical Logistic Regression. Stata J. 2009, 9, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, J.; Abraira, V.; Muriel, A.; Khan, K.; Coomarasamy, A. Meta-DiSc: A software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, J.; Fischetti, C.; Shniter, I.; Fox, J.C.; Lahham, S.; Abrams, E.; Thompson, M.; Saadat, S.; To, T. 70 Accuracy of Point-of-Care Ultrasound by Emergency Physicians in Diagnosis of Diastolic Cardiac Dysfunction When Compared to 2D Echocardiogram by Cardiology. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2019, 74, S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program], Version 5.4.1; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2020.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Suspected Non STEACS; Tomaszewski, C.A.; Nestler, D.; Shah, K.H.; Sudhir, A.; Brown, M.D. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Emergency Department Patients with Suspected Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 72, e65–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Brozek, J.; Glasziou, P.; Jaeschke, R.; Vist, G.E.; Williams, J.W., Jr.; Kunz, R.; Craig, J.; Montori, V.M.; et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008, 336, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnav, J.; Chasler, J.E.; Lee, Y.J.; Ndumele, C.E.; Hu, J.R.; Schulman, S.P.; Russell, S.D.; Sharma, K. Highest Obesity Category Associated with Largest Decrease in N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjan, V.Y.; Loftus, T.M.; Burke, M.A.; Akhter, N.; Fonarow, G.C.; Gheorghiade, M.; Shah, S.J. Prevalence, clinical phenotype, and outcomes associated with normal B-type natriuretic peptide levels in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M.; Schraft, E.; O’Brien, J.; Patel, D. Diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence for identifying systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction in the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 86, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Year) | Sample Size (n) | Male (%) | Age ± SD (Years) | Definition of DD by EP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ünlüer et al. (2012) [10] | 69 |

| ||

| NR | 63 ± 9 |

| ||

| ||||

| Ehrman et al. (2015) [11] | Diastolic dysfunction graded by simplified 2009 ASE criteria using Doppler and TDI: | |||

| 62 | 48% | 56 ± 14 |

| |

| ||||

| Moeller et al. 2019 [25] | 20 | NR | NR | NR |

| Lin et al. (2021) [12] |

| |||

| 176 | 65% | 64 ± 14 |

| |

|

| Study (Year) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PLR | NLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ünlüer et al. (2012) [10] | 89% (77 to 96) | 80% (52 to 96) | 4.44 (1.6 to 12.28) | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.31) |

| Ehrman et al. (2015) [11] | 100% (87 to 100) | 47% (23 to 72) | 1.89 (1.21 to 2.96) | 0 ** |

| Moeller et al. (2019) [25] | 100% (82 to 100) | 100% (2.5 to 100) | not estimable * | 0 ** |

| Lin et al. (2021) [12] | 93% (87 to 96) | 53% (34 to 72) | 1.98 (1.35 to 2.92) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.28) |

| Summary Point | Estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| sensitivity | 94% | 87% to 97% |

| specificity | 59% | 42% to 74% |

| PLR | 2.27 | 1.55 to 3.33 |

| NLR | 0.11 | 0.05 to 0.21 |

| Pre-Test Probability | PLR = 2.27 | NLR = 0.11 |

| 10% | 20.1% | 1.2% |

| 20% | 36.2% | 2.7% |

| 30% | 49.3% | 4.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, S.-M.; Yeh, Y.-H.; Sun, C.-K.; Chu, H.-W. Accuracy of Emergency Physician-Performed Echocardiography for Diastolic Dysfunction in Suspected Acute Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7726. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217726

Huang S-M, Yeh Y-H, Sun C-K, Chu H-W. Accuracy of Emergency Physician-Performed Echocardiography for Diastolic Dysfunction in Suspected Acute Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7726. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217726

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Shao-Min, Yu-Hsuan Yeh, Cheuk-Kwan Sun, and Hsuan-Wei Chu. 2025. "Accuracy of Emergency Physician-Performed Echocardiography for Diastolic Dysfunction in Suspected Acute Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7726. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217726

APA StyleHuang, S.-M., Yeh, Y.-H., Sun, C.-K., & Chu, H.-W. (2025). Accuracy of Emergency Physician-Performed Echocardiography for Diastolic Dysfunction in Suspected Acute Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7726. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217726