Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Pseudohypercalcemia in Paraproteinemia: A Case and Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

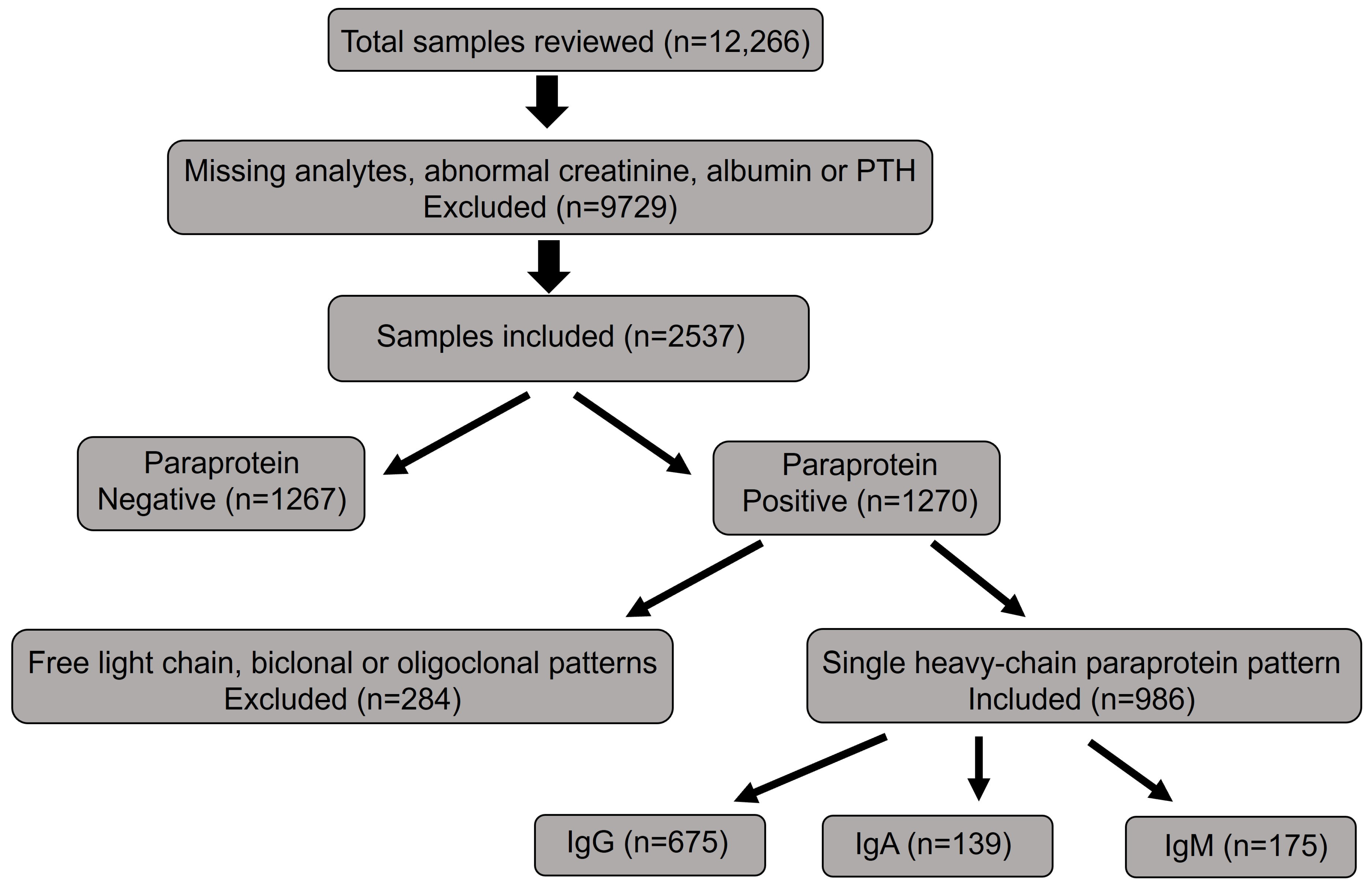

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Case Scenario

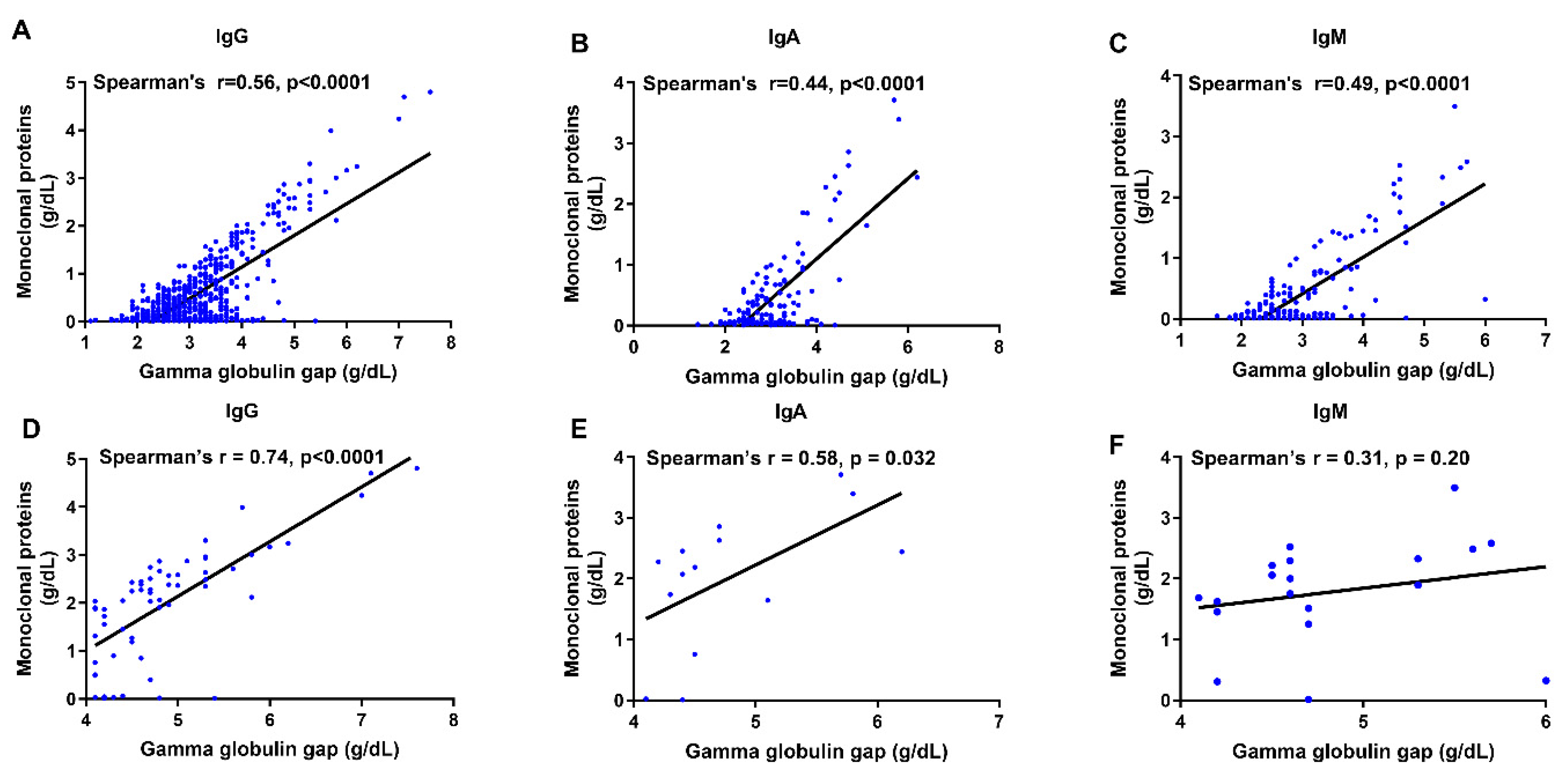

3.2. Subtype-Specific Relationships Between Monoclonal Proteins and Gamma Globulin Gap or Hypercalcemia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sakr, M.F. Calcium: Why Is It Important? In Parathyroid Gland Disorders: Controversies and Debates; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen, N.; Pekkarinen, T.; Ryhänen, E.M.; Schalin-Jäntti, C. Physiology of calcium homeostasis: An overview. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 2021, 50, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.D.; Shane, E. Hypercalcemia: A Review. JAMA 2022, 328, 1624–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkiewicz, P.; Kunachowicz, D.; Filipski, M.; Stebel, A.; Ligoda, J.; Rembiałkowska, N. Hypercalcemia in cancer: Causes, effects, and treatment strategies. Cells 2024, 13, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.I. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 2021, 50, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisa, M.O.; Saadi, S.; Nayfeh, T.; Muthusamy, K.; Shah, S.H.; Firwana, M.; Hasan, B.; Jawaid, T.; Abd-Rabu, R.; Korytkowski, M.T.; et al. A Systematic Review Supporting the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on the Treatment of Hypercalcemia of Malignancy in Adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, C.R.; Silva, T.A.A.L.; Pereira, F.W.L.; Queiroz, D.A.R.; Junior, E.L.F.; Martins, D.; Azevedo, P.S.; Okoshi, M.P.; Zornoff, L.A.M.; de Paiva, S.A.R.; et al. A review of current clinical concepts in the pathophysiology, etiology, diagnosis, and management of hypercalcemia. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e935821-1–e935821-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghumman, G.M.; Haider, M.; Raffay, E.A.; Cheema, H.A.; Yousaf, A. Hypercalcemia-induced hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with hypophosphatemia in a multiple myeloma patient: Lessons for the clinical nephrologist. J. Nephrol. 2023, 36, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzamzamy, O.M. Targeting Calcium Homeostasis for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Ph.D. Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, A.J.; Green, D.J.; Kwok, M.; Lee, S.; Coffey, D.G.; Holmberg, L.A.; Tuazon, S.; Gopal, A.K.; Libby, E.N. Diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma: A review. JAMA 2022, 327, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyajobi, B.O. Multiple myeloma/hypercalcemia. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007, 9 (Suppl. S1), S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R.A.; Rajkumar, S.V. Multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.F. Clinical practice. Hypercalcemia associated with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R.A.; Rajkumar, S.V. Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2009, 23, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Myeloma bone disease: Pathophysiology and management. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.H.; Wagar, E.A. Laboratory approaches for the diagnosis and assessment of hypercalcemia. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2015, 52, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishima, C.; Yakushijin, K.; Fukuoka, H.; Takahashi, R.; Okazoe, Y.; Joyce, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Sakai, R.; Inui, Y.; Kurata, K.; et al. A Rare Case of Pseudohypercalcemia Associated with Multiple Myeloma. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2025, 71, E46–E49. [Google Scholar]

- Mennens, S.F.; Van der Spek, E.; Ruinemans-Koerts, J.; Van Borren, M.M. Hematologists/Physicians Need to Be Aware of Pseudohypercalcemia in Monoclonal Gammopathy: Lessons from a Case Report. Case Rep. Hematol. 2024, 2024, 8844335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, C.J.; Hine, T.J.; Peek, K. Hypercalcaemia due to calcium binding by a polymeric IgA kappa-paraprotein. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1991, 28, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, R.; Oleesky, D.; Issa, B.; Scanlon, M.F.; Williams, C.P.; Harrison, C.B.; Child, D.F. Pseudohypercalcaemia in two patients with IgM paraproteinaemia. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1997, 34, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfatih, A.; Anderson, N.R.; Fahie-Wilson, M.N.; Gama, R. Pseudo-pseudohypercalcaemia, apparent primary hyperparathyroidism and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia. J. Clin. Pathol. 2007, 60, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portales-Castillo, I.; Jalal, A.; Kendall, P.L.; Parks, D. Normal Levels of Ionized Calcium Despite Persistent Increase in Total Calcium in a Patient With IgA Paraproteinemia. JCEM Case Rep. 2024, 2, luad163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Li, X.; Huang, B.; Gu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Li, J. The identification and correction of pseudohypercalcemia. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1441851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastritis, E.; Katodritou, E.; Pouli, A.; Hatzimichael, E.; Delimpasi, S.; Michalis, E.; Zomas, A.; Kartasis, Z.; Parcharidou, A.; Gika, D.; et al. Frequency and Prognostic Significance of Hypercalcemia in Patients with Multiple Myeloma: An Analysis of the Database of the Greek Myeloma Study Group. Blood 2011, 118, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Howanitz, P.J.; Howanitz, J.H.; Gorfajn, H.; Wong, K. Paraproteins are a common cause of interferences with automated chemistry methods. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2008, 132, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, R. Paraprotein Interferences: Insights from a Short Study Involving Multiple Platforms and Multiple Measurands. EJIFCC 2024, 35, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tCa (mg/dL) | 13.5 | 12.5 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 10.8 |

| iCa (mmol/L) | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.18 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.18 | 1.23 |

| Test | Results (Reference Range) |

|---|---|

| Calcium | 13.0 mg/dL (8.6–10.3) |

| Ionized calcium | 1.22 mmol/L (1.15–1.29) |

| Albumin | 3.1 g/dL (4.2–5.5) |

| Total protein | 9.8 g/dL (6.0–8.3) |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) | 43.3 pg/mL (8.7–77.1) |

| PTH-related protein (PTHrP) | <2.0 pmol/L (<2.0) |

| Vitamin D | 40.7 ng/mL (30–100) |

| Calcitriol (1,25-OH vitamin D) | 38.5 pg/mL (19.9–79.3) |

| κ/λ light chain ratio | 1.56 (0.26–1.65) |

| IgG | 5540 mg/dL (635–1741) |

| IgA | 23 mg/dL (45–281) |

| IgM | 32 mg/dL (66–433) |

| IgG κ M-protein | 4.4 g/dL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sunusi, U.; Chen, L.; Li, N.; Lee, J.K.Y.; Siddiqui, I.; Goodhue, E.; Huang, R.; Li, J. Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Pseudohypercalcemia in Paraproteinemia: A Case and Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217676

Sunusi U, Chen L, Li N, Lee JKY, Siddiqui I, Goodhue E, Huang R, Li J. Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Pseudohypercalcemia in Paraproteinemia: A Case and Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217676

Chicago/Turabian StyleSunusi, Usman, Li Chen, Nianyi Li, Jason K. Y. Lee, Irmeen Siddiqui, Erin Goodhue, Rongrong Huang, and Jieli Li. 2025. "Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Pseudohypercalcemia in Paraproteinemia: A Case and Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217676

APA StyleSunusi, U., Chen, L., Li, N., Lee, J. K. Y., Siddiqui, I., Goodhue, E., Huang, R., & Li, J. (2025). Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Pseudohypercalcemia in Paraproteinemia: A Case and Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7676. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217676