Beyond Mortality: Textbook Outcome as a Novel Quality Metric in Cardiothoracic Surgical Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

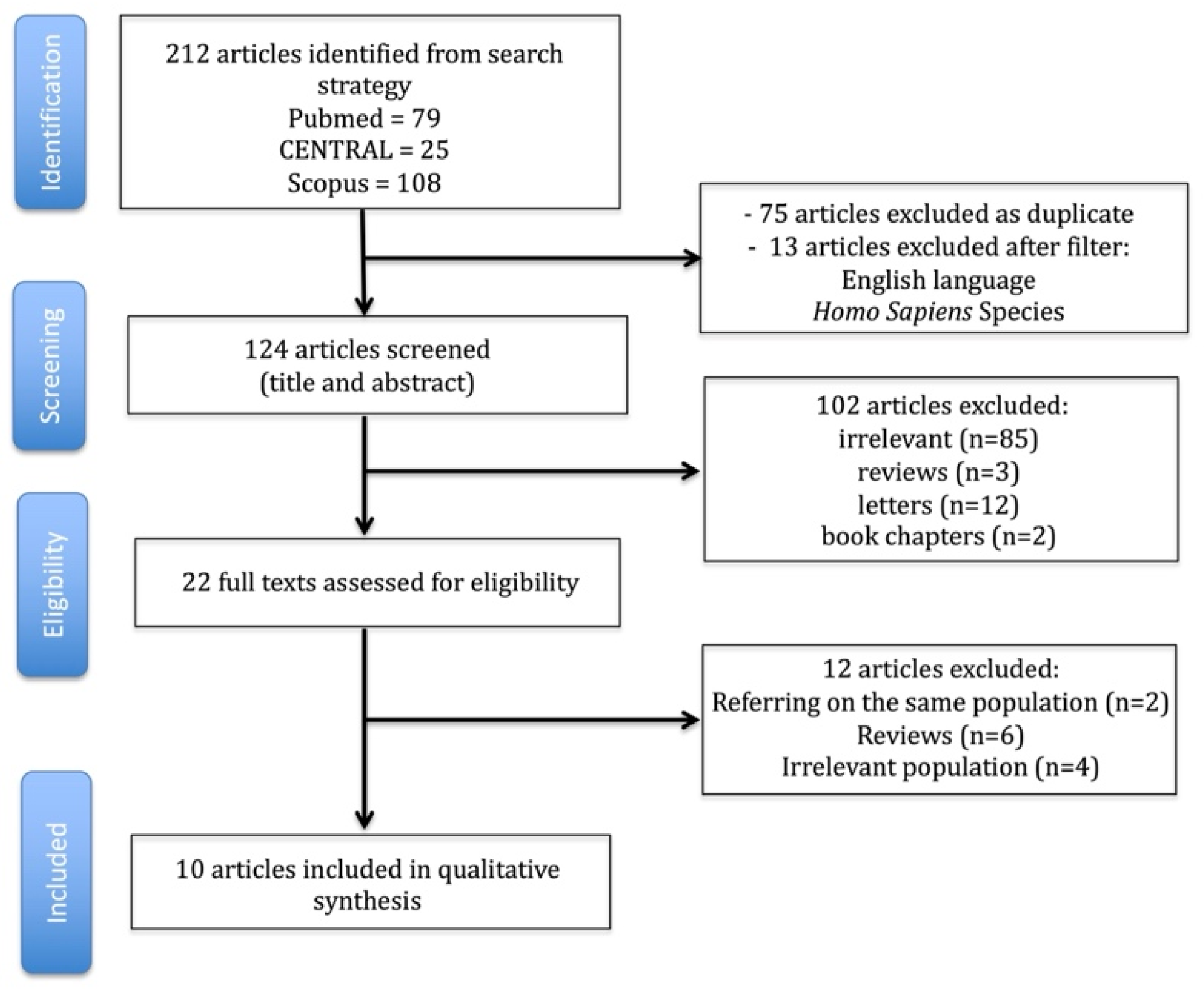

2.1. Search, Article Selection, and Data Extraction Strategy

2.2. Quality and Publication Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Definition of Textbook Outcome

| Procedure | Core Components of TO | Procedure-Specific Additions/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NSCLC resection | R0 resection; adequate lymph node dissection; no in-hospital/30-day mortality; no major complications or reintervention; no ICU readmission; no prolonged length of stay (often >14 d); no 30-day readmission | Nodal adequacy was frequently the dominant driver of non-TO in population datasets [5,6] |

| Esophagectomy (MIE/open) | R0 resection; ≥15 nodes; no major complications; no ICU readmission; length of stay ≤21 d; no 30-day readmission | Radical lymphadenectomy often specified; TO sensitive to operative-time efficiency [7,10,14,19,21] |

| Lung transplantation (single-center) | Early extubation (≤48 h); no PGD3 at 72 h; no ECMO/dialysis; no early rejection; no reintubation/tracheostomy within 7 d; no major in-hospital complications | Transplant-specific ventilatory/graft milestones measurable in institutional datasets [8,9] |

| Lung transplantation (US registry) | Freedom from: intubation at 72 h; ECMO at 72 h; ventilation ≥5 d; PGD3 at 72 h; inpatient dialysis; airway dehiscence; 90-day mortality; index length of stay >30 d; 30-day readmission; pre-discharge acute rejection | Standardized UNOS fields enable national benchmarking and adjusted O:E TO rates [15] |

| Norwood operation (congenital) | Survival without ECMO, cardiac arrest, reintubation, or reintervention; no 30-day readmission; invasive ventilation <10 d; index length of stay <66 d | Operation-specific, consensus-derived composite aligned with STS elements [16] |

| Heart transplantation (adult, OPTN/UNOS 10-item) | Index: LOS ≤30 d; no stroke/dialysis/treated rejection. One-year: EF >50%, Karnofsky 80–100%, no treated rejection/graft failure/chronic dialysis/retransplant/death | Enables O:E TO rates for center benchmarking; TO associated with long-term survival [17] |

| Heart transplantation (adult, OPTN/UNOS 6-domain) | No ECMO ≤72 h; LOS <21 d; no postoperative stroke/pacemaker/dialysis; no PGD; no 1 y readmission for rejection/infection/re-transplant; EF >50% at 1 y | Higher discriminatory power than 1 y survival; quantifies inter-hospital variation [18] |

3.2. Incidence of TO and Drivers of Failure

3.3. Determinants of TO and Risk Adjustment

3.4. Prognostic Impact

3.5. Health Economics and Benchmarking

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Why TO Is Clinically Useful

4.3. Sources of Heterogeneity and What They Mean

4.4. Equity, Social Determinants, and Risk Adjustment

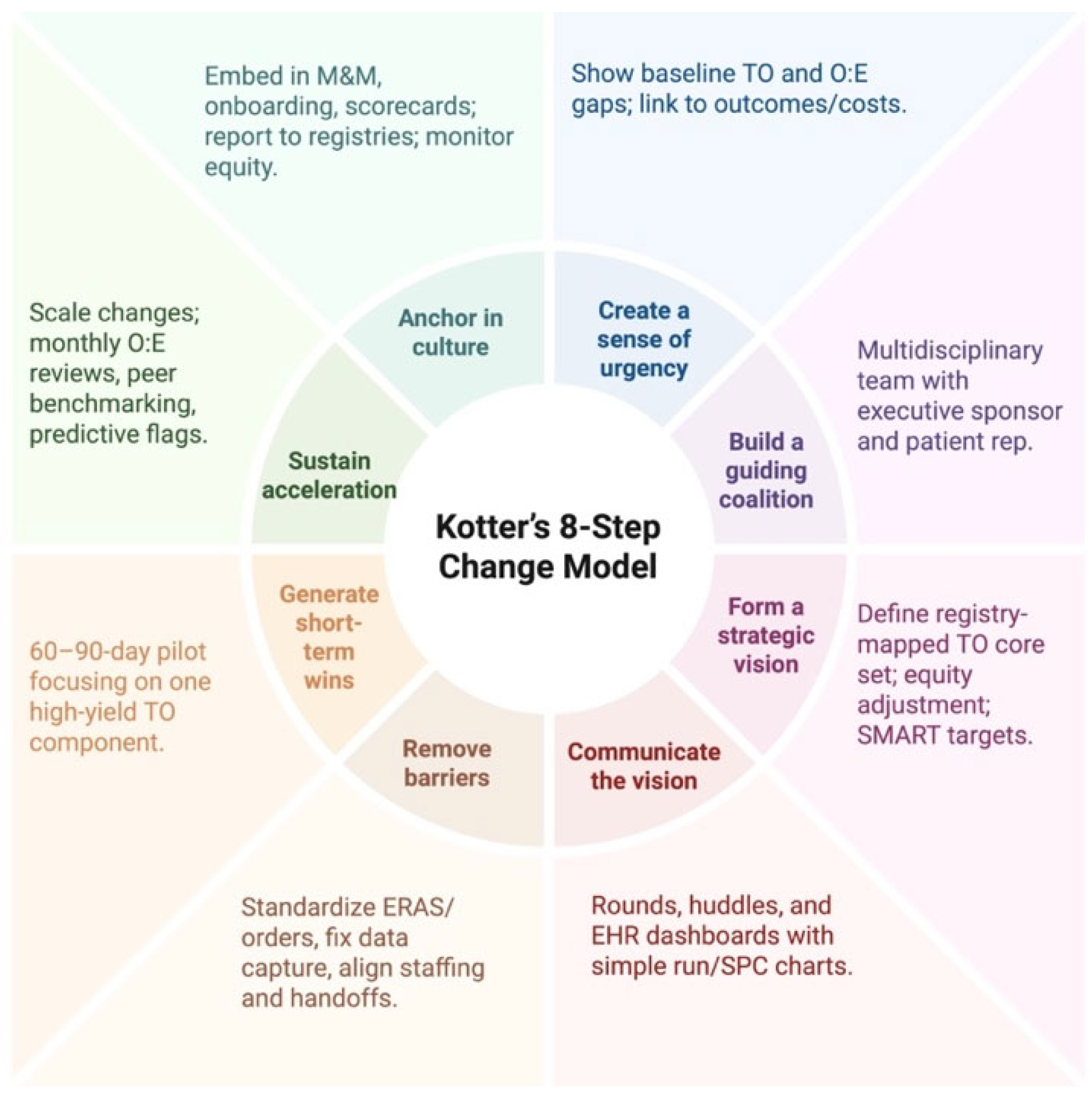

4.5. Implementation Playbook (Kotter-Guided)

- Create urgency: share local baseline TO and O:E gaps; pair with clinical vignettes;

- Build a coalition: surgeon, anesthesia, ICU, ward nursing, oncology/transplant, case management, informatics, finance, patient rep;

- Form a vision: define a registry-mapped TO core set per procedure; prespecify equity adjustment; set SMART targets;

- Communicate: rounds/huddles; simple run/SPC charts on the EHR dashboard;

- Remove barriers: standardize ERAS/order sets; fix data capture; align staffing/handoffs;

- Generate short-term wins: a 60–90-day pilot focused on one high-yield TO component;

- Sustain acceleration: monthly O:E reviews; peer benchmarking; predictive TO-risk flags;

- Anchor in culture: embed in M&M, onboarding, and scorecards; report to registries; monitor equity.

4.6. Limitations of the Evidence

4.7. Future Directions and Deliverables

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zotos, P.-A.; Androutsopoulou, V.; Scarci, M.; Minervini, F.; Cioffi, U.; Xanthopoulos, A.; Athanasiou, T.; Magouliotis, D.E. Failure to Rescue and Lung Resections for Lung Cancer: Measuring Quality from the Operation Room to the Intensive Care Unit. Cancers 2025, 17, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magouliotis, D.E.; Xanthopoulos, A.; Zotos, P.-A.; Rad, A.A.; Tatsios, E.; Bareka, M.; Briasoulis, A.; Triposkiadis, F.; Skoularigis, J.; Athanasiou, T. The Emerging Role of “Failure to Rescue” as the Primary Quality Metric for Cardiovascular Surgery and Critical Care. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warps, A.K.; Detering, R.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Tanis, P.J.; Dekker, J.W.T.; Dutch ColoRectal Audit group. Textbook outcome after rectal cancer surgery as a composite measure for quality of care: A population-based study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 2821–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realis Luc, M.; de Pascale, S.; Ascari, F.; Bonomi, A.M.; Bertani, E.; Cella, C.A.; Gervaso, L.; Fumagalli Romario, U. Textbook outcome as indicator of surgical quality in a single Western center: Results from 300 consecutive gastrectomies. Updates Surg. 2024, 76, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, M.G.T.; Beck, N.; Steup, W.H.; Verhagen, A.F.; van Brakel, T.J.; Schreurs, W.H.; Wouters, M.W.; Dutch Lung Cancer Audit for Surgery Group. Textbook outcome as a composite outcome measure in non-small-cell lung cancer surgery. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 59, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.S.; Shin, J.; Son, J.A.; Jung, J.; Haam, S. Assessment of textbook outcome after lobectomy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer in a Korean institution: A retrospective study. Thorac. Cancer 2022, 13, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.-J.; Lin, L.-Q.; Chen, C.; Chen, T.-Y.; You, C.-X.; Chen, R.-Q.; Deana, C.; Wakefield, C.J.; Shrager, J.B.; Molena, D.; et al. Textbook outcome after minimally invasive esophagectomy is an important prognostic indicator for predicting long-term oncological outcomes with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, S.E.B.; Moris, D.; Gloria, J.N.B.; Shaw, B.I.; Haney, J.C.; Klapper, J.A.; Barbas, A.S.; Hartwig, M.G.M. Textbook Outcome: Definition and Analysis of a Novel Quality Measure in Lung Transplantation. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, S.E.; Wright, M.C.; Madsen, G.; Chow, B.; Harris, C.S.; Haney, J.C.; Klapper, J.A.; Bottiger, B.A.; Hartwig, M.G. Textbook outcome in lung transplantation: Planned venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation versus off-pump support for patients without pulmonary hypertension. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Paredes, A.Z.; Sahara, K.; Moro, A.; Farooq, A.; White, S.; Ejaz, A.; Tsung, A.; Dillhoff, M.; et al. Comparing textbook outcomes among patients undergoing surgery for cancer at U. S. News & World Report ranked hospitals. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 121, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, S.E.; Moris, D.; Shaw, B.I.; Kesseli, S.J.; Samoylova, M.L.; Manook, M.; Schmitz, R.; Collins, B.H.; Sanoff, S.L.; Ravindra, K.V.; et al. Definition and Analysis of Textbook Outcome: A Novel Quality Measure in Kidney Transplantation. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, K.; Yu, B.; Yuan, C.; Qi, C.; Li, Z. Impact of operative time on textbook outcome after minimally invasive esophagectomy, a risk-adjusted analysis from a high-volume center. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 3195–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krischak, M.K.; Au, S.; Halpern, S.E.; Olaso, D.G.; Moris, D.; Snyder, L.D.; Barbas, A.S.; Haney, J.C.; Klapper, J.A.; Hartwig, M.G. Textbook surgical outcome in lung transplantation: Analysis of a US national registry. Clin. Transplant. 2022, 36, e14588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, N.K.; Nellis, J.R.; Moya-Mendez, M.; Hoover, A.; Medina, C.; Meza, J.M.; Allareddy, V.; Andersen, N.D.; Turek, J.W. Textbook outcome for the Norwood operation-an informative quality metric in congenital heart surgery. JTCVS Open 2023, 15, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakko, J.; Premkumar, A.; Logan, A.J.; Sneddon, J.M.; Brock, G.N.; Pawlik, T.M.; Mokadam, N.A.; Whitson, B.A.; Lampert, B.C.; Washburn, W.K.; et al. Textbook outcome: A novel metric in heart transplantation outcomes. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 167, 1077–1087.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiyar, S.S.; Sakowitz, S.; Ali, K.; Coaston, T.; Verma, A.; Chervu, N.L.; Benharash, P. Textbook outcomes in heart transplantation: A quality metric for the modern era. Surgery 2023, 174, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagkalos, E.; Grimminger, P.; Gao, X.; Chiu, C.-H.; Uzun, E.; Lang, H.; Wen, Y.-W.; Chao, Y.-K. Incidence and Predictors of Textbook Outcome after Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy for Cancer: A Two-Center Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnajar, A.; Razi, S.S.; Kodia, K.; Villamizar, N.; Nguyen, D.M. The impact of social determinants of health on textbook oncological outcomes and overall survival in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JTCVS Open 2023, 16, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busweiler, L.A.D.; Schouwenburg, M.G.; Henegouwen, M.I.v.B.; E Kolfschoten, N.; de Jong, P.C.; Rozema, T.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; van Hillegersberg, R.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; Dutch Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Audit (DUCA) group; et al. Textbook outcome as a composite measure in oesophagogastric cancer surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merath, K.; Chen, Q.; Bagante, F.; Beal, E.; Akgul, O.; Dillhoff, M.; Cloyd, J.M.; Pawlik, T.M. Textbook Outcomes Among Medicare Patients Undergoing Hepatopancreatic Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2020, 271, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, E.; Koliogiannis, D.; D’hAese, J.G.; Ilmer, M.; Guba, M.O.; Angele, M.K.; Werner, J.; Niess, H. Textbook outcome in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery: Systematic review. BJS Open 2022, 6, zrac149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slankamenac, K.; Graf, R.; Barkun, J.; Puhan, M.A.; Clavien, P.A. The comprehensive complication index: A novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimick, J.B.; Staiger, D.O.; Birkmeyer, J.D. Ranking hospitals on surgical mortality: The importance of reliability adjustment. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 45 Pt 1, 1614–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrighini, G.S.; Martinino, A.; Zecchin Ferrara, V.; Lorenzon, L.; Giovinazzo, F. Textbook oncologic outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1474008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsted, A.; Beck, A.W.; Banks, C.A.; Neal, D.; Columbo, J.A.; Robinson, S.T.; Stone, D.H.; Scali, S.T. A patient-centered textbook outcome measure effectively discriminates contemporary elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair quality. J. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 80, 1071–1081.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, E.; Levine, A.A.; Udyavar, N.R.; Burstin, H.R.; Bhulani, N.; Hoyt, D.B.; Ko, C.Y.; Weissman, J.S.; Britt, L.D.; Haider, A.H.; et al. Disparities in Surgical Access: A Systematic Literature Review, Conceptual Model, and Evidence Map. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 228, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyer, J.M.; Beane, J.D.; Spolverato, G.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Diaz, A.; Paro, A.; Dalmacy, D.; Pawlik, T.M. Trends in Textbook Outcomes over Time: Are Optimal Outcomes Following Complex Gastrointestinal Surgery for Cancer Increasing? J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2022, 26, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojevic, M.; Bond, C.; Theurer, P.F.; Jones, R.N.; Dabir, R.; Likosky, D.S.; Leyden, T.; Clark, M.; Prager, R.L. The Role of Regional Collaboratives in Quality Improvement: Time to Organize, and How? Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 32, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, A.C.; Magouliotis, D.E.; Milojevic, M.; Bond, C.J.; Clark, M.J.; Theurer, P.F.; Pagani, F.D.; Pruitt, A.L.; Prager, R.L. Lessons learned from the EACTS-MSTCVS quality fellowship: A call to action for continuous improvement of cardiothoracic surgery outcomes in Europe. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 64, ezad293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Procedure | Study/Cohort | N | TO rate | Leading Drivers of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC resection | Dutch Lung Cancer Audit | 5513 | 26.4% | Inadequate nodal dissection [5] |

| NSCLC resection | Korean single-center study | 418 | 66.3% | Prolonged air leak; prolonged LOS [6] |

| Esophagectomy (MIE) | China | 528 | 53.2% | Postoperative complications [7] |

| Esophagectomy (MIE) | Two-center study (EU/Asia) | 945 | 46.6% | Complications; inadequate lymphadenectomy [19] |

| Esophagectomy (MIE) | High-volume center | 2210 | 40.8% | Prolonged operative time; complications [14] |

| Lung transplantation | Academic single-center study | 401 | 24.2% | Delayed extubation [8] |

| Lung transplantation (US registry) | UNOS, 2016–2019 | 8959 | 52.1% | Intubation at 72 h; LOS >30 d; ventilation ≥5 d; PGD3 at 72 h [15] |

| Norwood operation (congenital) | Single-center study, 2005–2021 | 196 | 30% | Prolonged ventilation (49%); reintubation (46%); prolonged LOS (30%) [16] |

| Heart transplantation (adult) | OPTN/UNOS, 2005–2017 | 24,620 | 45.4% | Treated rejection during index stay; one-year rejection [17] |

| Heart transplantation (adult) | OPTN/UNOS, 2011–2022 | 26,885 | 37% | Early ECMO; prolonged LOS; PGD; 1 y EF ≤50%; readmission for rejection/infection [18] |

| Predictor/Effect | Setting | Adjusted Association |

|---|---|---|

| Older age; ASA ≥3; smoking; blood loss | Esophagectomy | Lower TO; worse OS/DFS [6,7] |

| Operative time >~298 min (inverse-U) | Esophagectomy (MIE) | Reduced TO beyond peak time [14] |

| Inadequate lymph node dissection | NSCLC resection | Strong determinant of non-TO [5] |

| Male sex; low DLCO | NSCLC lobectomy | Higher risk of non-TO [6] |

| Robotic vs. thoracoscopic approach | Esophagectomy | Higher TO with robotic [19] |

| Planned VA-ECMO vs. off-pump | Lung transplantation | Higher TO with planned ECMO [9] |

| Pretransplant ventilation/ECMO | Lung transplantation (UNOS) | Lower odds of TO; adverse case mix effects [15] |

| DCD donor; ischemic time (per hour); obesity; non-White race | Lung transplantation (UNOS) | Lower odds of TO; equity and donor factors [15] |

| Single- vs. bilateral transplant | Lung transplantation (UNOS) | Higher odds of TO with single lung [15] |

| TO achievement → patient/graft survival | Lung transplantation | Lower hazards of death and graft failure with TO [8,9,15] |

| Greater weight; absence of shock; shorter CPB | Norwood | Higher odds of TO [16] |

| TO achievement → lower costs | Norwood | Lower direct/total costs with TO [16] |

| No preop MCS/dialysis; not hospitalized | Heart transplant | Higher odds of TO [17,18] |

| TO achievement → long-term survival | Heart transplant | Substantially lower mortality hazards [17,18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magouliotis, D.E.; Androutsopoulou, V.; Zotos, P.-A.; Cioffi, U.; Minervini, F.; Sicouri, N.; Zacharoulis, D.; Xanthopoulos, A.; Scarci, M. Beyond Mortality: Textbook Outcome as a Novel Quality Metric in Cardiothoracic Surgical Care. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217660

Magouliotis DE, Androutsopoulou V, Zotos P-A, Cioffi U, Minervini F, Sicouri N, Zacharoulis D, Xanthopoulos A, Scarci M. Beyond Mortality: Textbook Outcome as a Novel Quality Metric in Cardiothoracic Surgical Care. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217660

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagouliotis, Dimitrios E., Vasiliki Androutsopoulou, Prokopis-Andreas Zotos, Ugo Cioffi, Fabrizio Minervini, Noah Sicouri, Dimitrios Zacharoulis, Andrew Xanthopoulos, and Marco Scarci. 2025. "Beyond Mortality: Textbook Outcome as a Novel Quality Metric in Cardiothoracic Surgical Care" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217660

APA StyleMagouliotis, D. E., Androutsopoulou, V., Zotos, P.-A., Cioffi, U., Minervini, F., Sicouri, N., Zacharoulis, D., Xanthopoulos, A., & Scarci, M. (2025). Beyond Mortality: Textbook Outcome as a Novel Quality Metric in Cardiothoracic Surgical Care. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217660