Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program to Improve Well-Being and Health in Healthcare Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

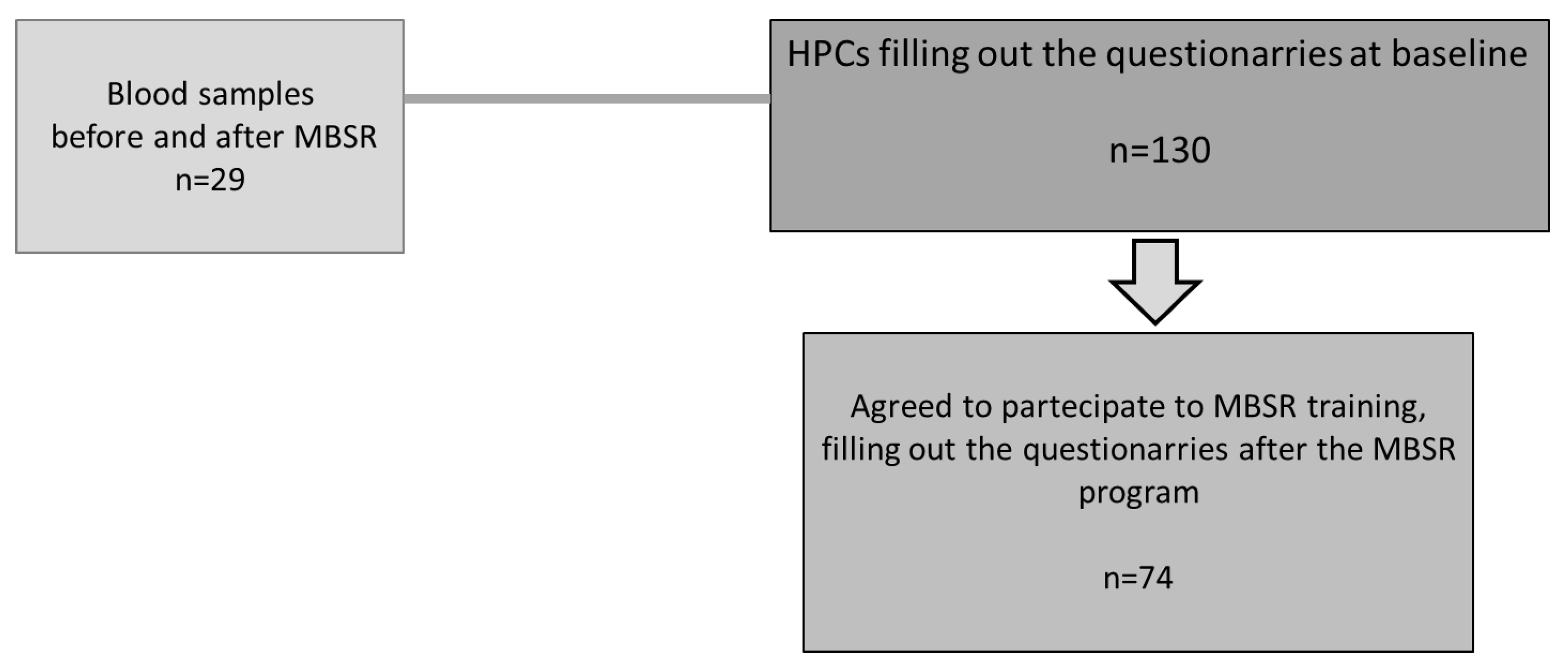

2.1. Study Sample and Procedures

2.2. Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

2.3. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Course

2.4. Questionnaires

2.5. Blood Samples

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Baseline Well-Being, Stress, and Burnout

3.2.1. Psychological General Well-Being Index

3.2.2. Perceived Stress Scale

3.2.3. Maslach Burnout Inventory

3.2.4. Reflections

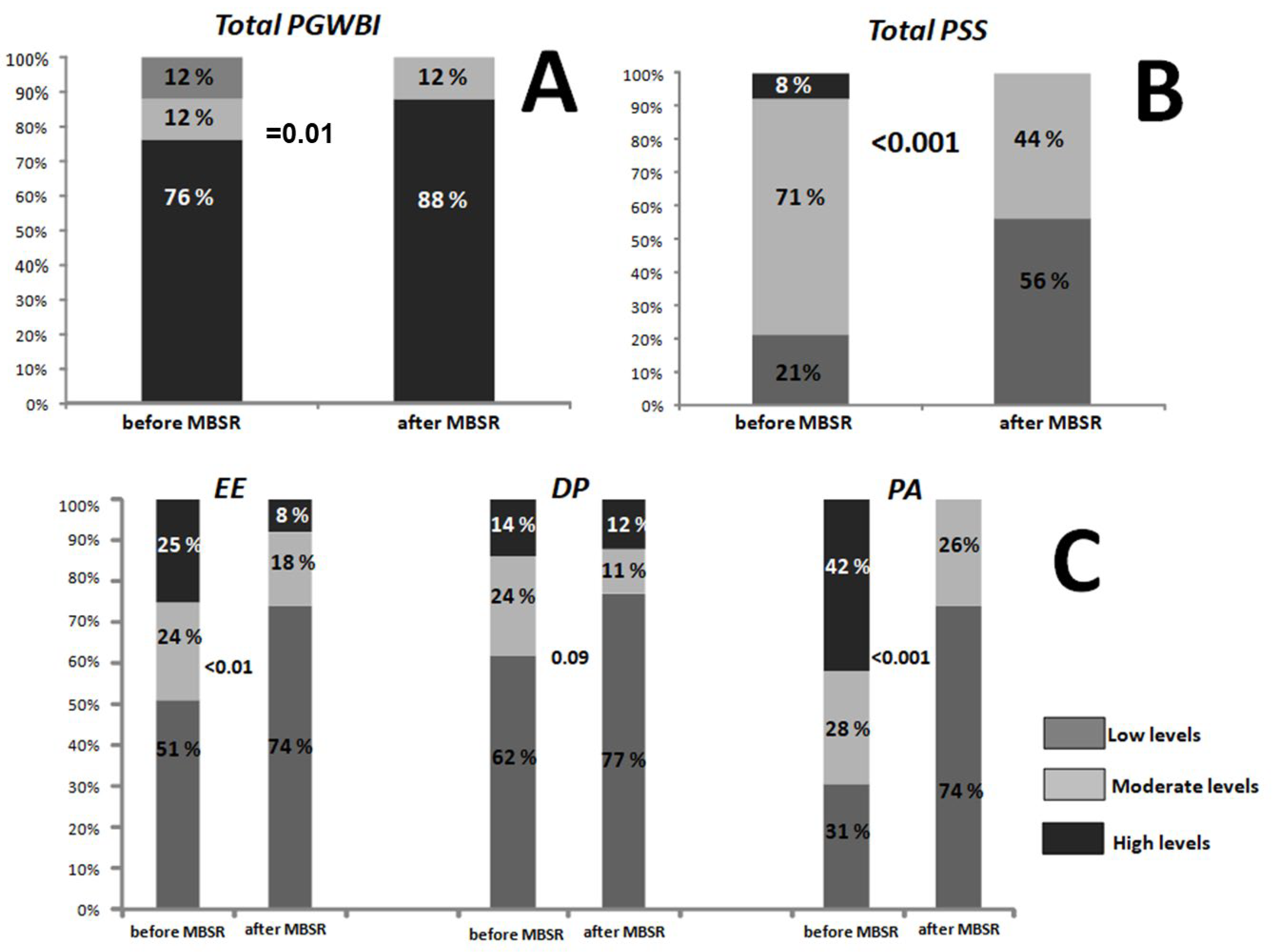

3.3. MBSR Effects

3.3.1. Psychological General Well-Being Index

3.3.2. Perceived Stress Scale

3.3.3. Maslach Burnout Inventory

3.3.4. Cardiometabolic Biomarkers

4. Discussion

4.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Studied Population

4.2. Well-Being, Stress, and Burnout

4.3. MBSR Effects

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rink, L.C.; Oyesanya, T.O.; Adair, K.C.; Humphreys, J.C.; Silva, S.G.; Sexton, J.B. Stressors Among Healthcare Workers: A Summative Content Analysis. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2023, 10, 23333936231161127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarino, V.; Bremner, J.D. Stress and cardiovascular disease: An update. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Gurgoglione, F.L.; Lazzeroni, D.; Halasz, G.; Niccoli, G. Effects of Static Meditation Practice on Blood Lipid Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.D.; Hayney, M.S.; Coe, C.L.; Ninos, C.L.; Barrett, B.P. Differential Reduction of IP-10 and C-Reactive Protein via Aerobic Exercise or Mindfulness-Based Stress-Reduction Training in a Large Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 41, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Patterson, J.S.; Tang, R.; Chi, J.; Ho, N.B.P.; Sears, D.D.; Gu, H. Metabolomic profiles impacted by brief mindfulness intervention with contributions to improved health. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zeng, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, B.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, J. Comprehensive metabolomic and lipidomic analysis reveals metabolic changes after mindfulness training. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, H.J.; Bin Mahmud, M.S.; Rajendran, P.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, W. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on psychological well-being, burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 2323–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh, J.M.; Khawaldeh, M.A.; Mrayyan, M.T.; Yehia, D.; Shudifat, R.M.; Anshasi, H.A.; Al-Shdayfat, N.M.; Alzoubi, M.M.; Aqel, A. The efficacy of mindfulness-based programs in reducing anxiety among nurses in hospital settings: A systematic review. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2024, 21, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajee, N.; Montero-Marin, J.; Saunders, K.E.A.; Myall, K.; Harriss, E.; Kuyken, W. Mindfulness training in healthcare professions: A scoping review of systematic reviews. Med. Educ. 2024, 58, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, I.; Bennie, J.A.; Charity, M.J.; van Uffelen, J.G.Z.; Harvey, J.T.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Eime, R.M. Participant characteristics of users of holistic movement practices in Australia. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 31, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.M.; Arigo, D.; Wolever, R.Q.; Smoski, M.J.; Hall, M.H.; Brantley, J.G.; Greeson, J.M. Do gender, anxiety, or sleep quality predict mindfulness-based stress reduction outcomes? J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 2656–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upchurch, D.M.; Johnson, P.J. Gender Differences in Prevalence, Patterns, Purposes, and Perceived Benefits of Meditation Practices in the United States. J. Womens Health 2019, 28, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojiani, R.; Santoyo, J.F.; Rahrig, H.; Roth, H.D.; Britton, W.B. Women Benefit More Than Men in Response to College-based Meditation Training. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadros, M.; Newby, J.M.; Li, S.; Werner-Seidler, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological treatments to improve sleep quality in university students. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, 0317125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, L.G.; Doty, J.L.; Diehl, D.C.; Nesbit, T.S.; Gage, N.A.; Kumbkarni, N.; Leon, S.P. Acceptability, usage, and efficacy of mindfulness apps for college student mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 367, 951–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsted, K.F. Mindfulness, Stress, and Aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 36, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1982, 4, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, M.; Gorini, F.; Parlanti, A.; Berti, S.; Vassalle, C. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on the Well-Being, Burnout and Stress of Italian Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.J.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Macchi, C.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Mediterranean diet and health status: An updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2769–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi, F.; Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Marcucci, R.; Casini, A. Validation of a literature-based adherence score to Mediterranean diet: The MEDI-LITE score. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, Z.E.; Wilson, M.J.; Benakovic, R.; Mackinnon, A.; Oliffe, J.L.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S.; Kealy, D.; Owen, J.; Pirkis, J.; Mihalopoulos, C.; et al. A randomized wait-list controlled trial of Men in Mind: Enhancing mental health practitioners’ self-rated clinical competencies to work with men. Am. Psychol. 2024, 79, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A.; Lam, C.N.; Stussman, B.; Yang, H. Prevalence and patterns of use of mantra, mindfulness and spiritual meditation among adults in the United States. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Iwanski, A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodek, P.M.; Wong, H.; Norena, M.; Ayas, N.; Reynolds, S.C.; Keenan, S.P.; Hamric, A.; Rodney, P.; Stewart, M.; Alden, L. Moral distress in intensive care unit professionals is associated with profession, age, and years of experience. J. Crit. Care 2016, 31, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Coyle, L.; Opgenorth, D.; Bellows, M.; Dhaliwal, J.; Richardson-Carr, S.; Bagshaw, S.M. Moral distress and burnout among cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit healthcare professionals: A prospective cross-sectional survey. Can. Assoc. Crit. Care Nurses 2016, 27, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dodek, P.M.; Norena, M.; Ayas, N.; Wong, H. Moral distress is associated with general workplace distress in intensive care unit personnel. J. Crit. Care 2019, 50, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, E.; Deligiannidou, G.-E.; Kontogiorgis, C.; Giaginis, C.; Koutelidakis, A.E. Fostering Resilience and Wellness: The Synergy of Mindful Eating and the Mediterranean Lifestyle. Appl. Biosci. 2024, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remskar, M.; Western, M.J.; Osborne, E.L.; Maynard, O.M.; Ainsworth, B. Effects of combining physical activity with mindfulness on mental health and wellbeing: Systematic review of complex interventions. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2024, 26, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, E.B.; Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Britton, W.B. Mindfulness and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: State of the Evidence, Plausible Mechanisms, and Theoretical Framework. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2015, 17, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Brown, J.; Norris, E.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Hayes, E.; Lindson, N. Mindfulness for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 4, CD013696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darehzereshki, S.; Dehghani, F.; Enjezab, B. Mindfulness-based stress reduction group training improves sleep quality in postmenopausal women. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth-Cozens, J. Doctors, their wellbeing, and their stress. BMJ 2003, 326, 670–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, B.; McMunn, A. Gender differences in unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK Covid-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, G.; Schwartz, D.; Friger, M.; Sergienko, R.; Monsonego, A.; Slonim-Nevo, V.; Greenberg, D.; Odes, S.; Sarid, O. Gender Differences in Coping Strategies and Life Satisfaction Following Cognitive-Behavioral and Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Crohn’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruessner, L.; Barnow, S.; Holt, D.V.; Joormann, J.; Schulze, K. A cognitive control framework for understanding emotion regulation flexibility. Emotion 2020, 20, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghen, P.; Aikman, S.N.; Mirabito, G. Mindfulness Interventions in Older Adults for Mental Health and Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2025, 80, gbae205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, L.; Huang, S. The effect of mindfulness training on the psychological state of high-level athletes: Meta analysis and system evaluation research. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 43, 600–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wong, S.Y.; Zhong, C.C.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, L.; Lee, E.K.; Chung, V.C.; Sit, R.W. Which type and dosage of mindfulness-based interventions are most effective for chronic pain? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2025, 191, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Du, S. Effect of mindfulness-based interventions on people with prehypertension or hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Guo, Y.; Bai, J.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on psychosocial well-being and occupational-related outcomes among nurses in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. Crit. Care 2025, 38, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, B.A.A.; McKenna, N. A systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions to reduce ICU nurse burnout: Global evidence and thematic synthesis. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, V.; Menéndez-Crispín, E.J.; Sarabia-Cobo, C.; de Lorena, P.; Fernández-Rodríguez, A.; González-Vaca, J. Mindfulness-Based Intervention for the Reduction of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout in Nurse Caregivers of Institutionalized Older Persons with Dementia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts-de Jong, M.; Geurtsv, D.E.M.; Spinhoven, P.; Ruhé, H.G.; Speckens, A.E.M. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Mental Health Outcomes in Frontline Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniaci, G.; Daino, M.; Iapichino, M.; Giammanco, A.; Taormina, C.; Bonura, G.; Sardella, Z.; Carolla, G.; Cammareri, P.; Sberna, E.; et al. Neurobiological and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of a Deep Diaphragmatic Breathing Technique Based on Neofunctional Psychotherapy: A Pilot RCT. Stress Health 2024, 40, e3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckenberg, R.A.; Eddy, P.; Kent, S.; Wright, B.J. Do workplace-based mindfulness meditation programs improve physiological indices of stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 114, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, C.M.; de Geus, E.J.; Penninx, B.W. Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system predicts the development of metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2484–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinstroop, E.; Fliers, E.; Kalsbeek, A. Hypothalamic control of hepatic lipid metabolism via the autonomic nervous system. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 28, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamasaki, H. The Effects of Mindfulness on Glycemic Control in People with Diabetes: An Overview of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Medicines 2023, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ee, C.C.; Al-Kanini, I.; Armour, M.; Piya, M.K.; McMorrow, R.; Rao, V.S.; Naidoo, D.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Kroeger, C.M.; Sabag, A. Mindfulness-based interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr. Med. Res. 2025, 14, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Thompson, D.R.; Jenkins, Z.M.; Ski, C.F. Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 95, 156–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Marsland, A.L.; Cole, S.W.; Dutcher, J.M.; Greco, C.M.; Wright, A.G.C.; Brown, K.W.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Reduces Proinflammatory Gene Regulation but Not Systemic Inflammation Among Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosom. Med. 2024, 86, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | |

| 5 | 3.5 (1) |

| 8 | 2.5 (1) |

| 17 | 3.3 (1.1) |

| 19 | 2.7 (1) |

| 22 | 2.9 (1.2) |

| Total score | 15 (5) |

| Depressed mood | |

| 3 | 4.1 (1) |

| 7 | 3.4 (0.9) |

| 11 | 4.5 (1) |

| Total score | 12 (2.5) |

| Positive well-being | |

| 1 | 2.5 (1) |

| 9 | 2.6 (1.1) |

| 15 | 3 (1.2) |

| 20 | 2.7 (1) |

| Total score | 11 (3.5) |

| Self-control | |

| 4 | 3 (1.2) |

| 14 | 4.1 (1.4) |

| 18 | 2.8 (1.1) |

| Total score | 10 (3) |

| General health | |

| 2 | 3.1 (1.3) |

| 10 | 3.6 (1.1) |

| 13 | 3.4 (1.1) |

| Total score | 10 (2) |

| Vitality | |

| 6 | 3.1 (0.9) |

| 12 | 2.4 (1.1) |

| 16 | 2.9 (1) |

| 21 | 3.3 (0.9) |

| Total score | 11.7 (3.2) |

| Total PGWBI score | 70 (16) |

| Items and Total Score | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| l. In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 1.7 (1.2) |

| 2. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | 1.9 (1.2) |

| 3. In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed? | 2.9 (0.9) |

| 4. In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? | 1.5 (1) |

| 5. In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way? | 1.8 (0.9) |

| 6. In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | 2.4 (1) |

| 7. In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life? | 1.9 (0.8) |

| 8. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things? | 1.7 (0.8) |

| 9. In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that happened that were outside of your control? | 2.3 (1) |

| 10. In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? | 1.8 (1.2) |

| Total PSS | 20 (7) |

| Items | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion (EE) | |

| 1 | 2.5 (1.8) |

| 2 | 3.4 (1.5) |

| 3 | 3 (1.7) |

| 6 | 1.8 (1.8) |

| 8 | 2.3 (1.9) |

| 13 | 1.9 (1.8) |

| 14 | 2.4 (1.9) |

| 16 | 1.5 (1.6) |

| 20 | 1.5 (1.8) |

| Total score | 20 (12) |

| Depersonalization and detachment from the job (DP) | |

| 5 | 1 (1.5) |

| 10 | 1.4 (1.8) |

| 11 | 2 (2.1) |

| 15 | 0.5 (1.1) |

| 22 | 0.7 (1.3) |

| Total score | 5.6 (6) |

| Lack of personal or professional accomplishment (PA) | |

| 4 | 4.6 (1.6) |

| 7 | 5 (1.1) |

| 9 | 4.4 (1.6) |

| 12 | 3.7 (1.5) |

| 17 | 4.5 (1.4) |

| 18 | 4.5 (1.5) |

| 19 | 4.2 (1.6) |

| 21 | 3.9 (1.8) |

| Total score | 34.7 (7.8) |

| Major Areas | Stressor Categories | Specific Stressors | Subjects | Examples of Reported Discomfort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work stressors | Systems-Level Stressors | Work demands and responsibility | both sexes, elderly | #52, male, 67 yrs “I feel discomfort with finding research funding and project deadlines” #94, male, 57 yrs; #123, female, 56 yrs “I feel a burden of responsibility, especially towards my employees” |

| Systems-level work barriers | both sexes, elderly | #147, male 46 yrs “increased complexity of work while my ability to respond decreased” #62, female, 53 yrs “fear of lack of tools (time, lack of supplies) that do not allow the patient’s needs to be met” #149, female 58 yrs “excessive workload together with lack of time for myself, misunderstandings between colleagues” | ||

| Time-related stressors | both sexes of various ages | #103, female, 56 yrs “it stresses me out to work quickly and not dedicate the left amount of time to the patient and to preparing the work” #96, female, 50 yrs “time to update superiors and colleagues, to discuss mistakes or positive aspects and to better organize activities” | ||

| Relationships | Team member relationships | females of various ages | #53, female, 53 yrs “stress due to inadequacy of superiors which affects the work process and consequently the quality of care” #131, female, 54 yrs “reduced process optimization—lack of dialogue” #126, female, 42 yrs “hectic work, lack of comparison” #144, female, 37 yrs “relationship with superiors, there is no dialogue” #118, female 52 yrs “I feel little trust from superiors and colleagues with whom there is little communication” #119, female 49 yrs “listening to constant comments from colleagues—interruptions at work—solving problems that I don’t think are within my competence” #146, female, 40 yrs “relationships with superiors, which show they don’t believe in my possibilities” #116, female, 24 yrs “the relationship with the other departments is difficult, they don’t seem to give the left value to my work and don’t try to solve the problems” #87, female, 37 yrs; #92, female, 31 yrs; #143, female, 42 yrs “relationship with patients and colleagues” #74, female, 29 yrs; #75, female 39 yrs; #112, female, 47 yrs “relationships with colleagues” | |

| Relationships with patients | females of various ages | #145, female, 35 yrs “Patient hostility and lack of appreciation” #120, female, 35 yrs “-being in contact with patients’ pain -not so much the workload but the relationships with colleagues” #100, female, 35 yrs “inadequacy in the face of clinical and human situations, especially when children are involved” #107, female, 40 yrs, “the relationship with the patients stresses me out and I feel exhausted, frustrated and angry at the end of the shift” #68, female, 53 yrs “accept that I can’t do anything, especially for the children. deal with the aggression of parents who accuse you of having made a mistake and blame you for their child’s illness” #69, female, 26 yrs “working with children, relating to the patient’s family, accepting that we cannot do more #115, female, 34 yrs “working in pediatrics means adding the parents’ anxieties and fears to the patient’s well-being. It is not easy to detach oneself from the situations experienced eight hours a day” | ||

| Individual work stressors | Personal concerns | both sexes of various ages | #122, female, 53 yrs “fear of losing empathy” #140, female 34 yrs “I can’t detach myself from situations with patients and colleagues -I’m detached towards patients -I don’t feel valued -I suffer because my difficulties can weigh on my colleagues” #58, male, 28 yrs “physical tiredness, colleagues’ judgement” #148, female, 35 yrs “relationship with patients: I can’t manage them with the necessary calm and pressure and I don’t feel valued professionally, I’ve lost enthusiasm” #60, female, 25 yrs “fear of making mistakes, lack of confidence in my abilities” #63, female, 56 yrs “sense of inadequacy, relationship with colleagues, stress in seeking control” #67, female, 65 yrs “tiredness, heavy shifts, relatives needing care, children far away, I feel off” | |

| Professional growth and rewards | both sexes of various ages | #73, male, 55 yrs “grow culturally and be adequate and helpful to patients” #106, female, 32 yrs “I feel like I’m not being rewarded” #139, female, 34 yrs “I love my job, but it stresses me out to have to accept decisions from above without considering the ideas of those who live in the department. I don’t feel valued and I have difficulties in my family where I bring stress and tears” | ||

| Work and family balance | females of various ages | #70, female, 36 yrs “balancing home and work, and not having time for myself” #108, female, 27 yrs; #95, female 49 yrs “reconciling work and family” | ||

| General stressors | Finances and money | one young male | #86, male 33 yrs “stress from shifts, dissatisfaction with the contractual aspect of the category” | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marotta, M.; Grassi, N.; Pingitore, A.; Parlanti, A.; Berti, S.; Vassalle, C. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program to Improve Well-Being and Health in Healthcare Professionals. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217655

Marotta M, Grassi N, Pingitore A, Parlanti A, Berti S, Vassalle C. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program to Improve Well-Being and Health in Healthcare Professionals. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217655

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarotta, Marco, Niccolo Grassi, Alessandro Pingitore, Alessandra Parlanti, Sergio Berti, and Cristina Vassalle. 2025. "Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program to Improve Well-Being and Health in Healthcare Professionals" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217655

APA StyleMarotta, M., Grassi, N., Pingitore, A., Parlanti, A., Berti, S., & Vassalle, C. (2025). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program to Improve Well-Being and Health in Healthcare Professionals. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217655