Comparison of Laparoscopic and Laparotomic Total Hysterectomy in Terms of Patient Satisfaction and Cosmetic Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

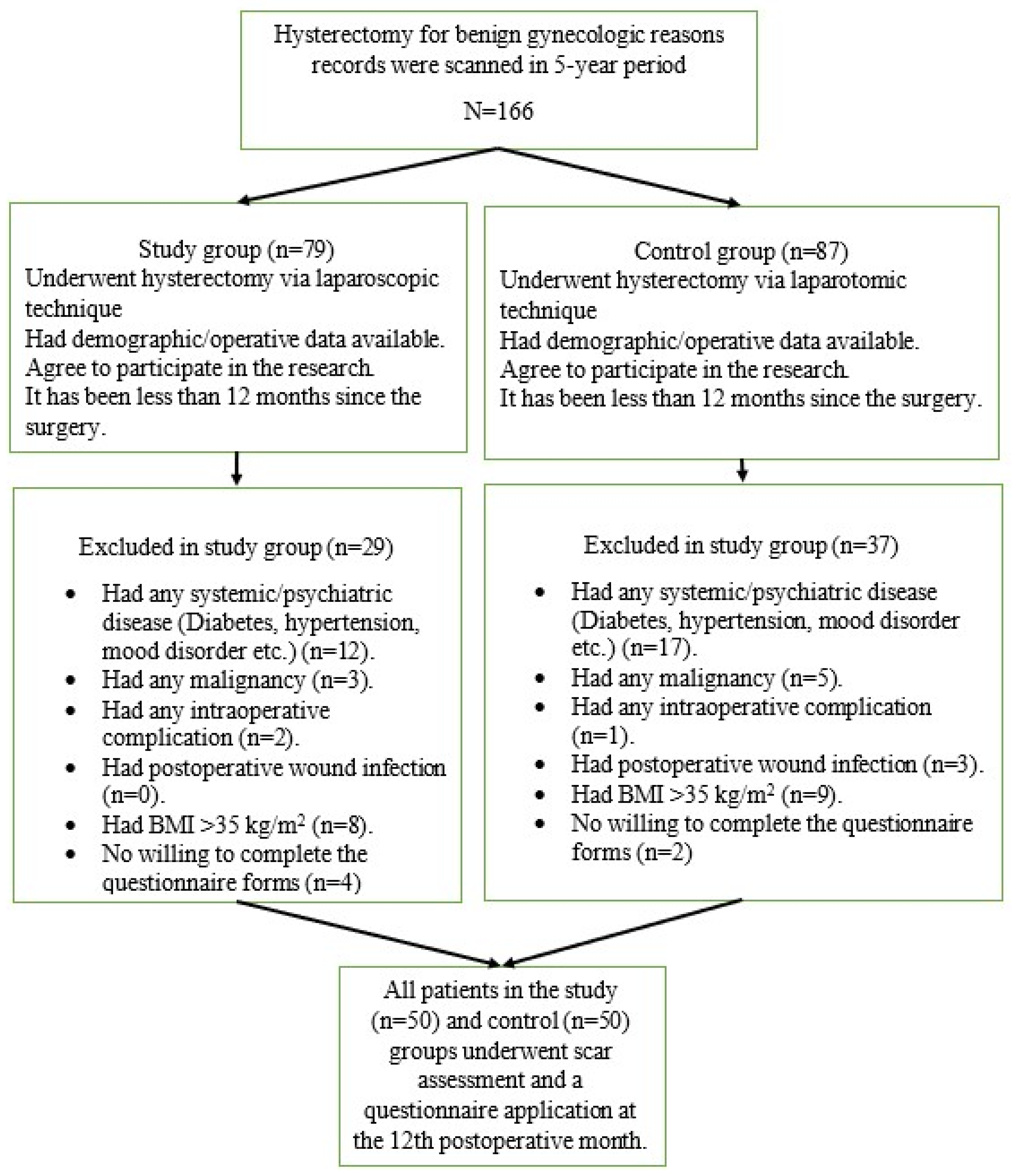

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Inclusion–Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Investigation Procedures

2.4. Manchester Scar Scale

2.5. Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS Patient)

2.6. Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS Observer)

2.7. Vancouver Scar Scale

2.8. Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating (SCAR) Scale

2.9. Body Image Questionnaire

2.10. Body-Cathexis Scale

2.11. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TLH | Total laparoscopic hysterectomy |

| VH | Vaginal hysterectomy |

| LH | Laparotomic hysterectomy |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| POSAS | Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale |

| SCAR | Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating |

| BCS | Body-Cathexis Scale |

References

- Papadopoulos, M.S.; Tolikas, A.C.; Miliaras, D.E. Hysterectomy: Current methods and alternatives for benign indications. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2010, 2010, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brummer, T.H.; Jalkanen, J.; Fraser, J.; Heikkinen, A.M.; Kauko, M.; Makinen, J.; Puistola, U.; Sjoberg, J.; Tomas, E.; Harkki, P. FINHYST 2006—National prospective 1-year survey of 5,279 hysterectomies. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, J.W.; Nieboer, T.E.; Johnson, N.; Tavender, E.; Garry, R.; Mol, B.W.; Kluivers, K.B. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD003677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, K.S.; Auld, B.J. A randomised prospective study of laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy each with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1994, 101, 1068–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrzenski, A.; Radolinski, B.; Ostrzenska, K.M. A review of laparoscopic ureteral injury in pelvic surgery. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2003, 58, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculpher, M.; Manca, A.; Abbott, J.; Fountain, J.; Mason, S.; Garry, R. Cost effectiveness analysis of laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with standard hysterectomy: Results from a randomised trial. BMJ 2004, 328, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioana, J.T.M.; Voita-Mekeres, F.; Motofelea, A.C.; Ciprian, D.; Fulger, L.; Alexandru, I.; Tarta, C.; Stelian, P.; Bernad, E.S.; Teodora, H. Surgical Outcomes in Laparoscopic Hysterectomy, Robotic-Assisted, and Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy for Uterine and Cervical Cancers: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.J.; Jeon, J.E.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, T.J. Feasibility and Surgical Outcomes of Hybrid Robotic Single-Site Hysterectomy Compared with Single-Port Access Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.; Smith, J.; Kermode, J.; McIver, E.; Courtemanche, D.J. Rating the burn scar. J. Burn. Care Rehabil. 1990, 11, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beausang, E.; Floyd, H.; Dunn, K.W.; Orton, C.I.; Ferguson, M.W. A new quantitative scale for clinical scar assessment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draaijers, L.J.; Tempelman, F.R.; Botman, Y.A.; Tuinebreijer, W.E.; Middelkoop, E.; Kreis, R.W.; van Zuijlen, P.P. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: A reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 1960–1965; discussion 1966–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, J. The SCAR (Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating) scale: Development and validation of a new outcome measure for postoperative scar assessment. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 1394–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuhadaroglu, F. Adolesanlarda Benlik Saygısı: Rosenberg Benlik Saygısı ölçeği’nin Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Türk Psikiyatr. Derg. 1986, 2, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood, P.; Fletcher, I.; Lee, A.; Al Ghazal, S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovardaoğlu, S. Vücut Algısı Ölçeği. Psikiyatri, Psikoloji, Psikofarmakoloji Dergisi (3P). Testler Özel Eki. 1992, 1, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis, T.E.; Galatianos, I.N.; Papaziogas, B.T.; Lazaridis, C.N.; Atmatzidis, K.S.; Makris, J.G.; Papaziogas, T.B. Complete dehiscence of the abdominal wound and incriminating factors. Eur. J. Surg. 2001, 167, 351–354; discussion 355. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Lu, J. Comparison of outcomes between laparoscopic and open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer in women with body mass index greater than 24. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2025, 51, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelghar, W.M.; El-Bishry, G.; Emam, L.H. Caesarean deliveries by Pfannenstiel versus Joel-Cohen incision: A randomised controlled trial. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2013, 14, 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari, Z.; Baratali, B.H.; Foroughifar, T.; Pesikhani, M.D.; Shariat, M. Pfannenstiel versus Maylard incision for gynecologic surgery: A randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 48, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lunacek, A.; Radmayr, C.; Horninger, W.; Plas, E. Pfannenstiel incision for radical retropubic prostatectomy as a surgical and cosmetic alternative to the midline or laparoscopic approach: A single center study. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2014, 67, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Sundaram, M.; Mahajan, C.; Raje, S.; Kadam, P.; Rao, G.; Shitut, P. Single-incision total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J. Minim. Access Surg. 2011, 7, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gencdal, S.; Aydogmus, H.; Aydogmus, S.; Kolsuz, Z.; Kelekci, S. Mini-Laparoscopic Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery for Benign Adnexal Masses. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2017, 9, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Raakow, J.; Klein, D.; Barutcu, A.G.; Biebl, M.; Pratschke, J.; Raakow, R. Single-port versus multiport laparoscopic surgery comparing long-term patient satisfaction and cosmetic outcome. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 5533–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, T.; Klarskov, B.; Trap, R.; Kehlet, H.; Rosenberg, J. Microlaparoscopic vs conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective randomized double-blind trial. Surg. Endosc. 2002, 16, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, W.K.; Lenzi, J.E.; So, J.B.; Kum, C.K.; Goh, P.M. Randomized trial of needlescopic versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br. J. Surg. 2001, 88, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arezzo, A.; Passera, R.; Bullano, A.; Mintz, Y.; Kedar, A.; Boni, L.; Cassinotti, E.; Rosati, R.; Fumagalli Romario, U.; Sorrentino, M.; et al. Multi-port versus single-port cholecystectomy: Results of a multi-centre, randomised controlled trial (MUSIC trial). Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 2872–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamabe, A.; Takemasa, I.; Hata, T.; Mizushima, T.; Doki, Y.; Mori, M. Patient Body Image and Satisfaction with Surgical Wound Appearance After Reduced Port Surgery for Colorectal Diseases. World J. Surg. 2016, 40, 1748–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pearl, M. Mini-laparotomy versus laparoscopy for gynecologic conditions. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014, 21, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulcinelli, F.M.; Schimberni, M.; Marci, R.; Bellati, F.; Caserta, D. Laparoscopic versus laparotomic surgery for adnexal masses: Role in elderly. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baum, S.; Alkatout, I.; Proppe, L.; Kotanidis, C.; Rody, A.; Lagana, A.S.; Sommer, S.; Gitas, G. Surgical treatment of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma—Laparotomy versus laparoscopy. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2022, 23, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.L.; Piedmonte, M.R.; Spirtos, N.M.; Eisenkop, S.M.; Schlaerth, J.B.; Mannel, R.S.; Spiegel, G.; Barakat, R.; Pearl, M.L.; Sharma, S.K. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5331–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, L.R.; Rosa, D.D.; Bozzetti, M.C.; Fachel, J.M.; Furness, S.; Garry, R.; Rosa, M.I.; Stein, A.T. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for benign ovarian tumour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2, CD004751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauglitz, G.G.; Korting, H.C.; Pavicic, T.; Ruzicka, T.; Jeschke, M.G. Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: Pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jina, N.H.; Marsh, C.; Than, M.; Singh, H.; Cassidy, S.; Simcock, J. Keratin gel improves poor scarring following median sternotomy. ANZ J. Surg. 2015, 85, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baryza, M.J.; Baryza, G.A. The Vancouver Scar Scale: An administration tool and its interrater reliability. J. Burn. Care Rehabil. 1995, 16, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.K.; Park, J.Y.; Shin, Y.H.; Yang, J.; Kim, H.Y. Reliability and validity of Vancouver Scar Scale and Withey score after syndactyly release. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2022, 31, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Hua, K.; Zhang, X. Comparison of two different methods for cervicovaginal reconstruction: A long-term follow-up. Int. Urogynecology J. 2023, 34, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.N.; Xin, W.J.; Li, X.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Hua, K.Q.; Ding, J.X. The role of oral oil administration in displaying the chylous tubes and preventing chylous leakage in laparoscopic para-aortic lymphadenectomy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 118, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, J.; Hua, K. Laparoscopic local extraperitoneal para-aortic lymphadenectomy: Description of a novel technique. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control Group (LH) | Study Group (TLH) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.34 ± 6.87 | 52.78 ± 7.66 | 0.020 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.80 ± 12.08 | 77.66 ± 15.51 | 0.683 |

| Height (cm) | 159.54 ± 5.23 | 159.98 ± 6.88 | 0.720 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.01 ± 4.95 | 30.3783 ± 5.9583 | 0.568 |

| Gravidity | 3.82 ± 2.11 | 4.02 ± 2.57 | 0.672 |

| Parity | 3.12 ± 1.74 | 3.34 ± 2.08 | 0.568 |

| Uterine volume (measurements during pathological examination) | 970.12 ± 1051.32 | 644.74 ± 478.25 | 0.05 |

| Uterus weight (grams) | 273.14 ± 329.01 | 194.46 ± 140.71 | 0.125 |

| Hospitalization duration (postoperative hospitalization duration) | 3.84 ± 0.76 | 3.00 ± 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Duration of antibiotics use (days) | 7.8 ± 1.47 | 7.62 ± 1.99 | 0.334 |

| Operative time/Anesthesia time (min) | 108.8 ± 21.5 | 164.0 ± 26.3 | <0.001 |

| Estimated blood flow (mL) | 477.4 ± 52.3 | 152.0 ± 33.3 | <0.001 |

| Control Group (LH, n = 50) | Study Group (TLH, n = 50) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total scar area (mm2) | 157.51 ± 96.37 | 109.68 ± 57.01 | 0.003 |

| Manchester Scale Score | 9.56 ± 2.61 | 9.02 ± 3.08 | 0.347 |

| POSAS Observer Scale Score | 16.28 ± 5.77 | 14.80 ± 8.97 | 0.329 |

| Vancouver Scale Score | 4.40 ± 2.59 | 3.48 ± 2.67 | 0.084 |

| SCAR Scale Score | 5.88 ± 2.68 | 5.3 ± 3.18 | 0.327 |

| Control Group (LH, n = 50) | Study Group (TLH, n = 50) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| POSAS Patient Scale Score | 15.78 ± 10.62 | 8.98 ± 3.53 | <0.001 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Score | 30.8 ± 5.64 | 29.41 ± 5.19 | 0.200 |

| Body Image Questionnaire Score | 17.68 ± 2.61 | 19.16 ± 1.87 | 0.002 |

| Body-Cathexis Scale Score | 147.14 ± 21.80 | 149.48 ± 14.21 | 0.526 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aydin, S.E.; Aran, T.; Guven, S. Comparison of Laparoscopic and Laparotomic Total Hysterectomy in Terms of Patient Satisfaction and Cosmetic Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217646

Aydin SE, Aran T, Guven S. Comparison of Laparoscopic and Laparotomic Total Hysterectomy in Terms of Patient Satisfaction and Cosmetic Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217646

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydin, Suheyla Erbasaran, Turhan Aran, and Suleyman Guven. 2025. "Comparison of Laparoscopic and Laparotomic Total Hysterectomy in Terms of Patient Satisfaction and Cosmetic Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217646

APA StyleAydin, S. E., Aran, T., & Guven, S. (2025). Comparison of Laparoscopic and Laparotomic Total Hysterectomy in Terms of Patient Satisfaction and Cosmetic Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217646