1. Introduction

With the increasing number of elective surgeries, optimizing preoperative preparation has become a priority [

1,

2]. Consequently, preoperative patient management is evolving rapidly and has become an essential component of patient-centered perioperative care [

3,

4]. This optimization is particularly relevant in the field of anesthesia, where the provision of clear and comprehensive information is crucial to ensure trust and to help the patient reach an informed decision [

5]. During the preoperative anesthetic assessment before surgery, the patient receives general information about anesthesia, their concerns are addressed, and specific information about their health status is obtained [

3]. Quality communication in the preanesthetic clinic has been shown to reduce patient anxiety, improve adherence to fasting and medication instructions, and enhance overall satisfaction with perioperative care [

6,

7]. Effective communication about treatment options and care plans is an essential part of shared decision-making, particularly when these decisions affect a patient’s health status [

7,

8].

In this context, digital education tools are being increasingly integrated into healthcare to standardize and clarify information delivery and promote patient empowerment [

9,

10]. Understanding how clinician-related factors interact with digital education is essential to ensuring equitable and effective patient preparation across diverse healthcare settings. However, the overall effectiveness of preoperative education depends not only on digital tools but also on the interpersonal interaction with the physician, especially during face-to-face visits, where factors such as physician gender and clinical experience may influence how patients respond to previously conveyed digital content. Previous studies have shown that gender differences among healthcare providers can influence satisfaction, visit duration, and outcomes of surgical patients [

11,

12,

13]. Patients’ expectations of physicians may also vary based on the physician’s gender [

14]. Similarly, research in clinical and training settings indicates that physician experience can enhance communication quality over time [

15,

16]. Unlike in other specialties, anesthesiologists often meet patients only once before surgery, making the quality of this single interaction particularly important. Despite these insights, few studies have specifically investigated how an anesthesiologist’s gender and clinical experience influence patients’ preoperative preparation [

17].

In our initial prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled iPREDICT study, we demonstrated that online education prior to an in-person preoperative visit significantly improves patients’ knowledge of anesthesia-related risks and promotes patient empowerment [

18]. Building on these findings, the present sub-analysis aimed to explore the role of interpersonal factors, specifically the gender of the anesthesiologist and level of clinical experience, in shaping patients’ preoperative preparation within the context of digital education. More specifically, this study examined whether individual physician characteristics influence patients’ understanding and recall of anesthesia-related risks, and whether anesthesiologist gender affects the reduction in patient anxiety after the face-to-face preoperative consultation. Furthermore, this sub-study aimed to clarify how these physician characteristics interact with digital education tools and influence communication quality in perioperative care.

2. Materials and Methods

The present sub-analysis investigated 275 adult patients who were scheduled for elective surgery under general anesthesia or combined regional and general anesthesia. They were recruited within the iPREDICT Trial from September 2023 to January 2025. The iPREDICT study was a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study conducted at the University Hospital Bonn, Germany [

18]. The study is registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (

https://drks.de/search/en/trial/DRKS00032514; accessed on 21 August 2023) (

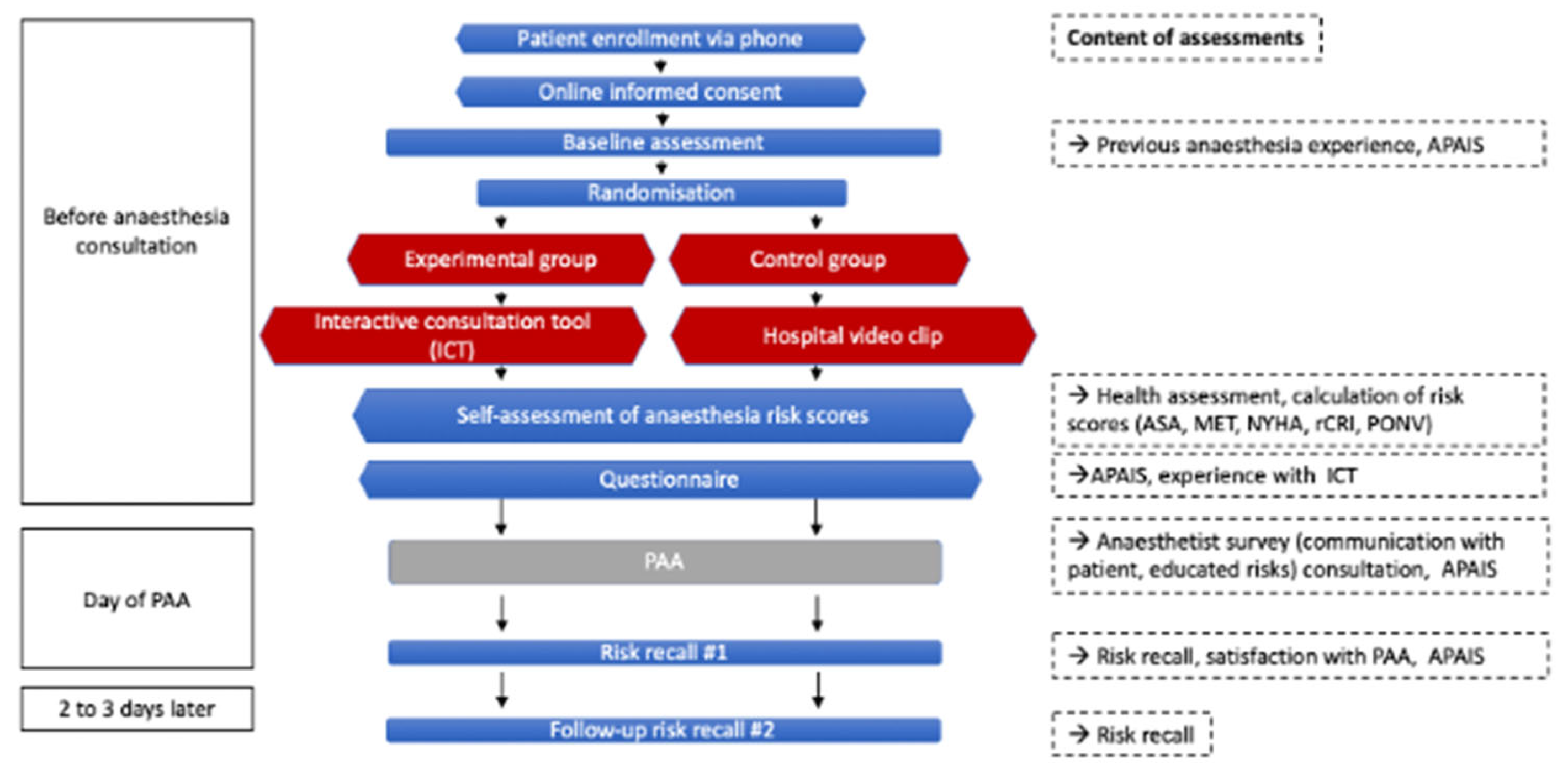

Figure 1).

Participants were enrolled in the study prior to their preoperative anesthetic assessment at the clinic and randomly assigned to an online anesthesia risk education in an experimental ICT group (Interactive consultation tool group) or to a control group that watched a video without any anesthetic risk content. Details of the trial design and procedures have been reported previously; only methods relevant to the present sub-analysis are summarized here [

18].

In addition to the baseline demographic and clinical data, data on the patient’s anesthesia-related anxiety levels and information needs in the preoperative phase were collected using the six-point Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) [

19]. On the day of the preoperative consultation, anesthesiologists completed a structured questionnaire documenting the quality of communication, the specific risks explained, and whether the patient declined a detailed explanation. The anesthesiologists who conducted the consultations were randomly assigned to patients according to the clinic’s appointment schedule. They were unaware of the patients’ group assignment (ICT group vs. control) and completed a standardized questionnaire immediately after each consultation. Patients completed a separate questionnaire evaluating their knowledge of potential risks and whether the consultation had alleviated their fears and concerns. Two days later, patients were surveyed again to assess retention of anesthesia-related risk information.

2.1. Outcome Parameters

The primary outcome of this sub-analysis was patients’ understanding of the risks associated with anesthesia after personal consultation, as well as the influence of gender and the anesthetist’s clinical experience on this parameter. In this context, risk understanding was defined as the patient’s overall comprehension of anesthesia-related risks following both digital and in-person education; risk recall referred to the number of individual risks the patient could correctly remember at each assessment time point; and risk explanation reflected the number of risks communicated by the anesthesiologist during the consultation.

Secondary outcomes included changes in patients’ preoperative anxiety levels, concern about anesthesia, and information needs measured with the APAIS score at three time points: at the baseline visit, after online education, and after the personal consultation. In addition, patients’ perceptions of consultation-related relief of fears and concerns were assessed. Further exploratory outcomes were as follows: the duration of the clinical consultation, the frequency with which patients asked questions, the effectiveness of communication between the patient and the anesthetist, and whether the patient refused the detailed educational explanation.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for key measures are stratified by the anesthesiologist’s gender, as well as the patient’s gender. Continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (Q1, Q3), and categorical variables as numbers with percentages. To examine differences in patient-reported anxiety levels, information needs, understanding of anesthesia-related risks, and perceived communication effectiveness, we applied linear mixed-effects models (LMMs). Fixed effects included patient age, patient gender, anesthesiologist gender and clinical experience, study group, with random intercepts for anesthesiologist. For understanding of anesthesia-related risks, random intercepts are additionally included for patients to account for repeated measurements at up to two time points, immediately after the consultation and during the online follow-up two days later. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, no adjustment for multiple testing was performed. Analyses were performed using R Version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

4. Discussion

In this sub-analysis of the iPREDICT trial [

18], we investigated the influence of anesthesiologist gender and clinical experience on preoperative patient preparation in the context of digital education. We demonstrated with the iPREDICT trial that online preoperative education prior to an in-person visit significantly improved patients’ knowledge of anesthesia-related risks over time. This sub-analysis found that anesthesiologist characteristics primarily affected aspects of communication and reassurance. Female anesthesiologists were more likely to alleviate patients’ fears, and anesthesiologists with 1–4 years of experience explained more risks compared to those with <1 year of experience. In contrast, communication quality was rated highest when anesthesiologists had more than 10 years of experience. Overall, preoperative anxiety was low, and recall of risks was largely determined by patient characteristics, particularly age, rather than anesthesiologist factors.

Given the exploratory nature of this analysis and the number of models tested, the results should be interpreted with caution. The wide confidence intervals for certain predictors suggest limited significance in some subgroups. The observed gender differences likely reflect complex communication and interpersonal factors rather than gender alone. However, our findings align with previous research suggesting that physician gender can influence patient satisfaction, trust, and communication quality [

20,

21]. Previous studies have shown that female physicians show more empathy and provide more psychosocial support, asking more questions and providing more information compared to their male colleagues [

22]. This may explain why patients reported greater relief from fear when the consultation was led by a female anesthesiologist. Also, this finding should be interpreted with caution, given the gender imbalance in our sample. Most consultations were conducted by female anesthesiologists, which may have influenced the overall direction of the observed effects.

Similarly, the observation that anesthesiologists in their early years of training explained more risks is consistent with earlier work showing that younger clinicians may adhere more strictly to protocols and provide more comprehensive risk disclosure, while experienced practitioners rely more on judgment [

23]. The group of anesthesiologists with 1–4 years of experience was the most thorough, probably because they have gained confidence, but still adhere strictly to protocol. Conversely, the higher communication ratings for anesthetists with longer professional experience probably reflect interpersonal skills acquired over time, even if detailed explanations of risks were less common. This pattern may reflect a trade-off between thoroughness and patient understanding: while young anesthesiologists provide detailed, protocol-oriented explanations, too much information can overwhelm patients [

24]. In contrast, experienced physicians often focus on clarity and relevance, which can improve patient understanding and reassurance [

15]. This clarity not only supports informed consent, but can also reduce perioperative stress and improve patient satisfaction—outcomes that are becoming increasingly important in modern anesthetic practice. The integration of an online education tool in the perioperative clinical practice proved significant advantages for patient empowerment and decision-making [

18]. The variability in risk recall was almost entirely due to patient factors, not the anesthesiologist, indicating the ICT (Interactive consultation tool) was more important for retention than who delivered the information. Importantly, this effect was independent of anesthesiologist gender or experience, suggesting that digital tools can standardize the delivery of essential information. At the same time, our data highlight that interpersonal interactions remain crucial for reducing preoperative fears and shaping the patient’s perception of communication quality. Together, these findings suggest that digital tools should complement, rather than replace, face-to-face consultations in preoperative education. Integrating such tools into routine practice can enhance patient understanding, while interpersonal communication remains essential for reducing anxiety and promoting trust. Patients who obtain basic knowledge in advance through online education are also better prepared to engage in meaningful dialog with the anesthesiologist, ask specific questions, and participate more actively in shared decision-making, which also reflects greater patient empowerment.

Targeted communication training, particularly for less experienced anesthesiologists, could further improve patient interactions [

25]. Future research should examine how combining digital preparation with structured communication approaches influences patient outcomes across diverse clinical and cultural settings. From a practical perspective, these findings underscore the importance of integrating digital education tools into structured communication training for anesthesiologists, particularly those early in their careers. Such training could help balance thoroughness and clarity, improve patient-centered communication, and ensure that digital and interpersonal approaches to preoperative care effectively complement each other. Integrating evidence-based digital tools into structured communication training could represent the next step toward a standardized yet individualized model of preoperative patient education.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its generalizability may be limited, as it was conducted in a single hospital in Germany with a moderate sample size derived from the iPREDICT trial. Furthermore, cultural norms and expectations regarding gender roles in physician–patient interactions may have influenced the results. As communication behaviors and patient perceptions can vary depending on the healthcare systems and cultural settings, the observed gender-related effects may not be directly generalizable to other countries. However, direct influence by the researchers on patient responses is unlikely, as the anesthetists who conducted the consultations were randomly assigned according to the schedule, had no knowledge of the allocation of patient groups, and followed a standardized procedure for preoperative documentation.

Second, the results are based on patient-reported measures, which are inherently subjective and may be influenced by individual expectations or perceptions. Finally, unmeasured factors—such as personal empathy, communication style, or the specific dynamics of each consultation—may have contributed to the observed differences and were not fully captured in this analysis.

Third, the study relied on patient-reported outcomes, such as the APAIS (Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale) and Likert-scale ratings. Although these are validated instruments, they remain subjective and may be influenced by individual expectations, rapport with the anesthesiologist, or unmeasured psychosocial factors. These potential biases should be considered when interpreting the results. Despite these limitations, the strengths of the study include the relatively large cohort and the systematic assessment of both patient and anesthetist characteristics, which together provide valuable insights into preoperative preparation.