Multinodular Hydropic Leiomyoma in a 41-Year-Old Patient: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

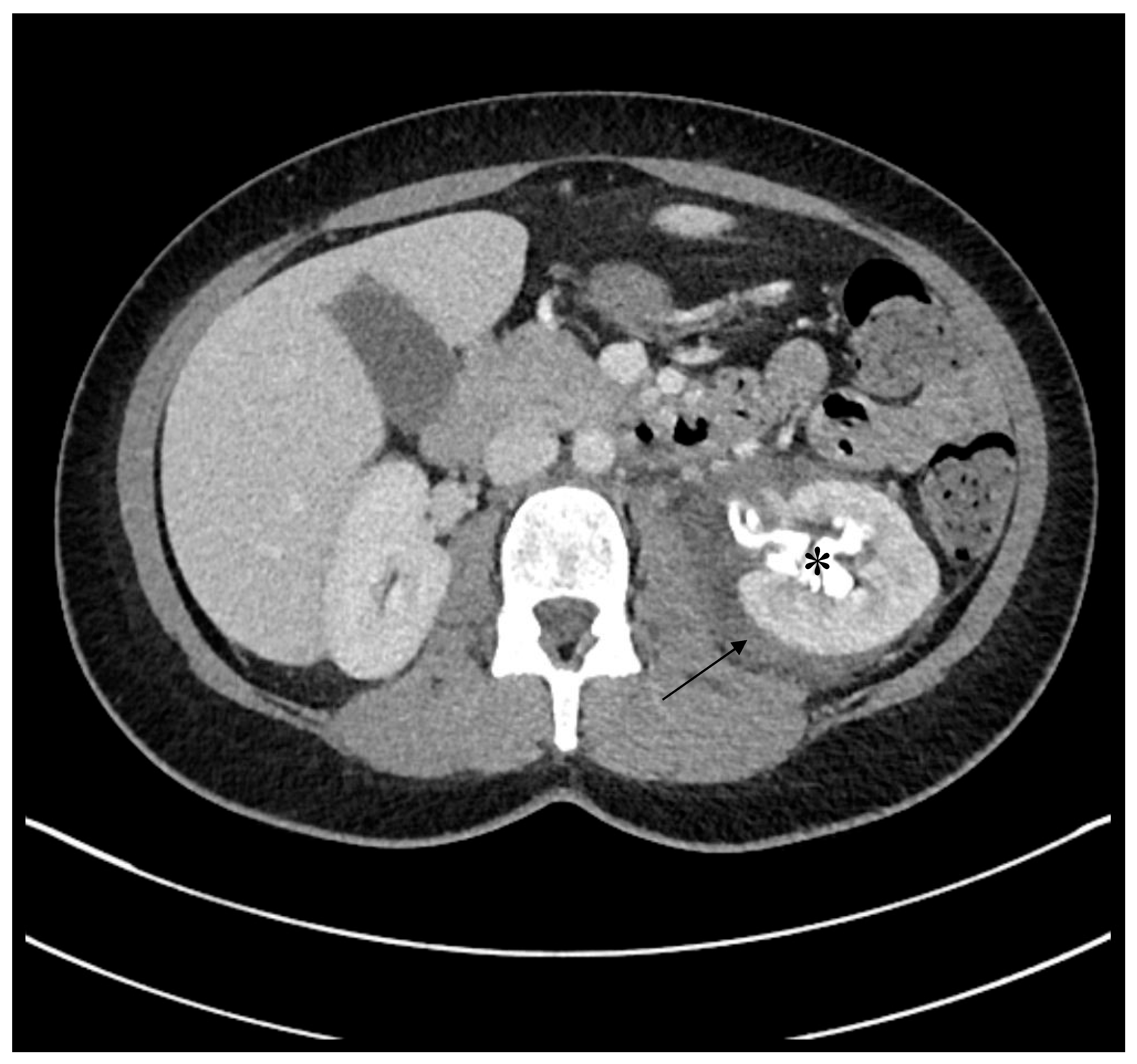

2. Case

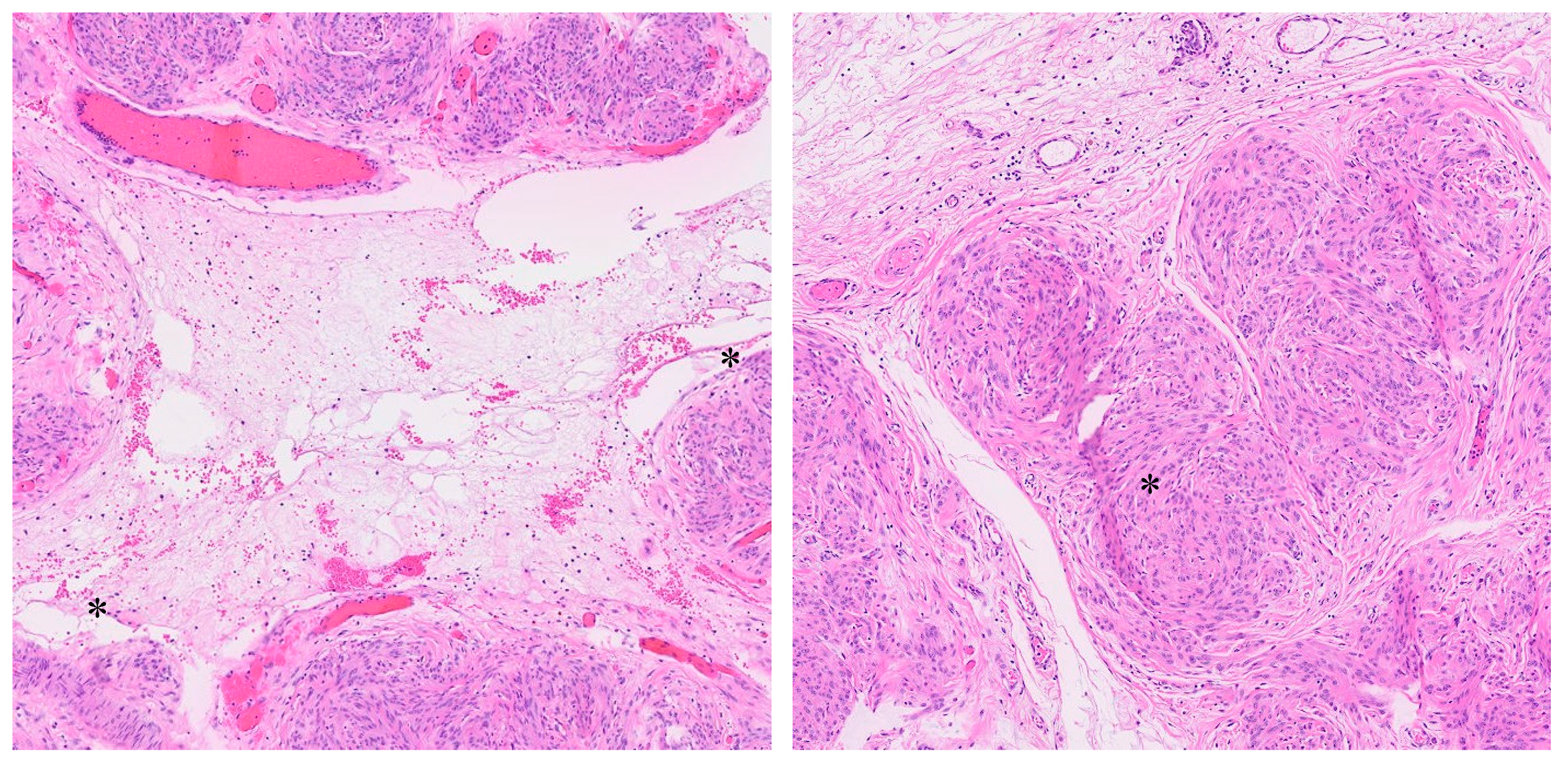

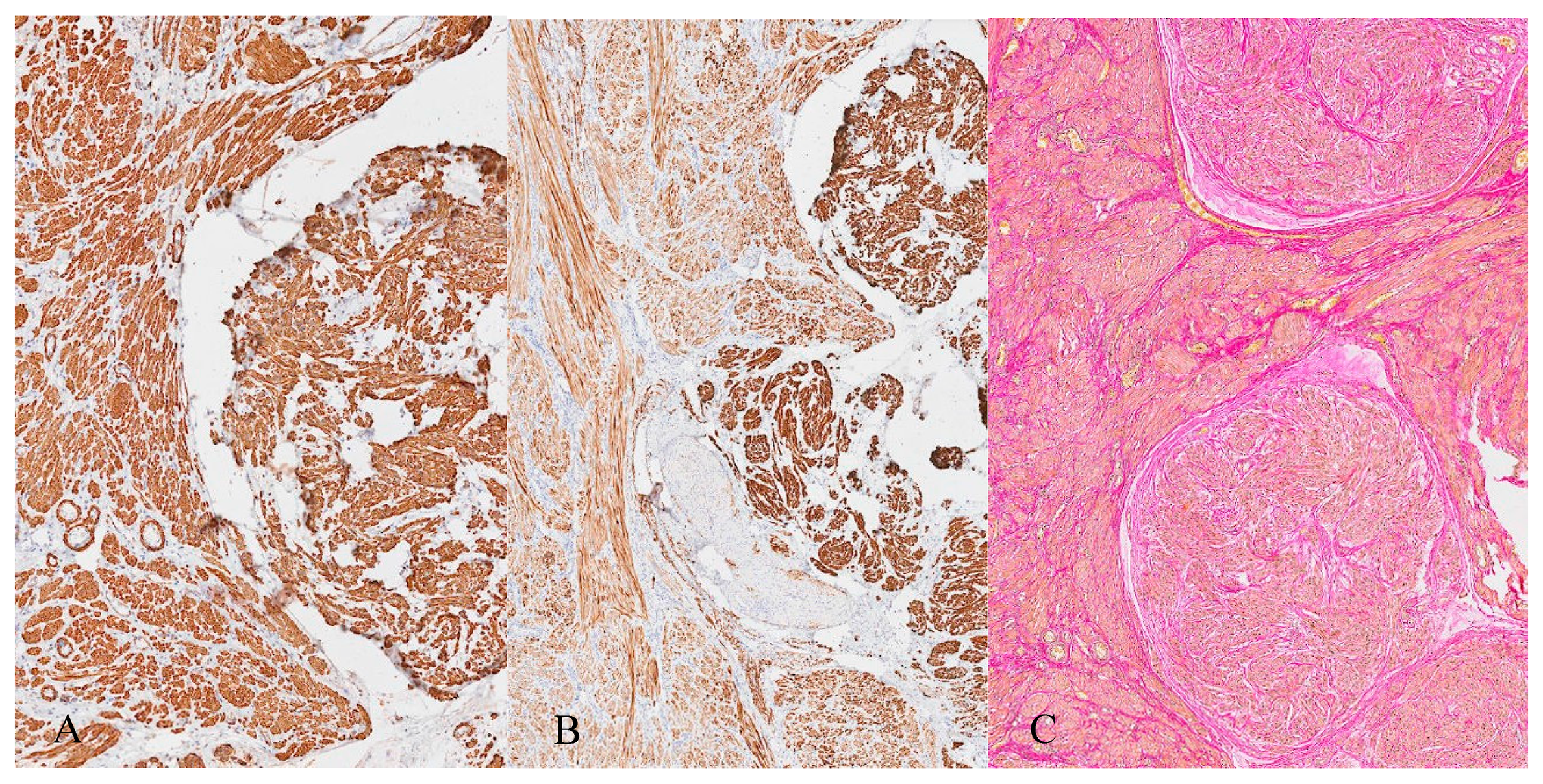

3. Histopathology

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnostic Challenges

4.2. Histopathology and Differential Diagnosis

4.3. Management

4.4. Complications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eggert, S.L.; Huyck, K.L.; Somasundaram, P.; Kavalla, R.; Stewart, E.A.; Lu, A.T.; Painter, J.N.; Montgomery, G.W.; Medland, S.E.; Nyholt, D.R.; et al. Genome-wide linkage and association analyses implicate FASN in predisposition to Uterine Leiomyomata. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day Baird, D.; Dunson, D.B.; Hill, M.C.; Cousins, D.; Schectman, J.M. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: Ultrasound evidence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.M.; Spiegelman, D.; Barbieri, R.L.; Goldman, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C.; Hunter, D.J. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 90, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, B.J.; Nicholson, W.K.; Bradley, L.; Stewart, E.A. The impact of uterine leiomyomas: A national survey of affected women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 209, 319.e1–319.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicinelli, E.; Romano, F.; Anastasio, P.S.; Blasi, N.; Parisi, C.; Galantino, P. Transabdominal sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography, and hysteroscopy in the evaluation of submucous myomas. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 85, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, D.; Fernandez, H.; Levaillant, J.M.; Capmas, P. Quality assessment of pelvic ultrasound for uterine myoma according to the CNGOF guidelines. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 46, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.M. Uterine fibroid management: From the present to the future. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seshadri, S.; El-Toukhy, T.; Douiri, A.; Jayaprakasan, K.; Khalaf, Y. Diagnostic accuracy of saline infusion sonography in the evaluation of uterine cavity abnormalities prior to assisted reproductive techniques: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffone, A.; Raimondo, D.; Neola, D.; Travaglino, A.; Giorgi, M.; Lazzeri, L.; De Laurentiis, F.; Carravetta, C.; Zupi, E.; Seracchioli, R.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI in the differential diagnosis between uterine leiomyomas and sarcomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 165, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valletta, R.; Corato, V.; Lombardo, F.; Avesani, G.; Negri, G.; Steinkasserer, M.; Tagliaferri, T.; Bonatti, M. Leiomyoma or sarcoma? MRI performance in the differential diagnosis of sonographically suspicious uterine masses. Eur. J. Radiol. 2024, 170, 111217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMulder, D.; Ascher, S.M. Uterine Leiomyosarcoma: Can MRI Differentiate Leiomyosarcoma From Benign Leiomyoma Before Treatment? AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018, 211, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, K.; Murakami, K.; Kaji, Y.; Sugimura, K. Spectrum of FDG PET/CT findings of uterine tumors. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rha, S.E.; Byun, J.Y.; Jung, S.E.; Lee, S.L.; Cho, S.M.; Hwang, S.S.; Lee, H.G.; Namkoong, S.E.; Lee, J.M. CT and MRI of uterine sarcomas and their mimickers. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003, 181, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Management of Symptomatic Uterine Leiomyomas: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 228. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 137, e100–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, S.F. New features in the 2014 WHO classification of uterine neoplasms. Pathologe 2016, 37, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kınay, T.; Ergani, S.; Dağdeviren, G.; Akpinar, F.; Mesci, Ç.; Karakaya, J.; Altinbas, S.; Tapisiz, O.; Kayikcioglu, F. Characteristics that distinguish leiomyoma variants from the ordinary leiomyomas and recurrence risk. Gulhane Med. J. 2022, 64, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhan, K.; Şimşir, C.; Dölen, I.S.; Çalýşkan, E.; Umudum, H. Multinodular hydropic leiomyoma of the uterus with perinodular hydropic degeneration and extrauterine extension. Pathol. Int. 2002, 52, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghali, E.H.; Meziyane, J.; Auragh, S.; Saadi, H.; Taheri, H.; Mimouni, A. Hydropic leiomyoma, a considerable differential diagnosis: A case series. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 11, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkour, K.; Alhulwah, M.; Alqahtani, N.; Arafah, M.A. A Giant Leiomyoma with Massive Cystic Hydropic Degeneration Mimicking an Aggressive Neoplasm: A Challenging Case with a Literature Review. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e929085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, H.; Chiang, S.; Dickinson, S.; Chi, D.S.; Kim, S.H. When it’s not ovarian cancer: A case of a massive leiomyoma with hydropic change. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 53, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Lou, J.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. Pseudo-Meigs syndrome caused by a rapidly enlarging hydropic leiomyoma with elevated CA125 levels mimicking ovarian malignancy: A case report and literature review. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horta, M.; Cunha, T.M.; Oliveira, R.; Magro, P. Hydropic leiomyoma of the uterus presenting as a giant abdominal mass. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Kyozuka, H.; Kochi, Y.; Ito, F.; Odajima, H.; Suzuki, D.; Nomura, Y. Hydropic leiomyoma-like ovarian tumor: A case report. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2024, 70, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lameira, P.; Filipe, J.; Cabeçadas, J.; Cunha, T.M. Hydropic leiomyoma: A radiologic pathologic correlation of a rare uterine tumor. Radiol. Case Rep. 2022, 17, 3151–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.B.; Ban, Y.; Lu, X.; Wei, J.J. Hydropic leiomyoma: A distinct variant of leiomyoma closely related to HMGA2 overexpression. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 84, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, G.; Lima, M.; Gil, R.; Horta, M.; Cunha, T.M. T2 hyperintense myometrial tumors: Can MRI features differentiate leiomyomas from leiomyosarcomas? Abdom. Radiol. 2019, 44, 3388–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.R.; Nandikoor, S.; Padilu, R. Hydropic degeneration of leiomyoma in nongravid uterus: The “split fiber” sign on magnetic resonance imaging. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2018, 28, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, P.B.; Young, R.H.; Scully, R.E. Diffuse, perinodular, and other patterns of hydropic degeneration within and adjacent to uterine leiomyomas. Problems in differential diagnosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1992, 16, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, J.E.; Sulaiman, R.A.; Das, K.; Staley, N. Perinodular hydropic degeneration of a uterine leiomyoma: A diagnostic challenge. Hum. Pathol. 1997, 28, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.C.; Gold, M.A.; Wile, G.; Fadare, O. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus: A review of clinical, pathological, and radiological features. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 20, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-N.; Jang, J.; Kim, K.-R. Uterine Leiomyomas with Perinodular Hydropic Degeneration—A Report of Two Cases. Korean J. Pathol. 2002, 36, 257–261. Available online: https://www.jpatholtm.org/upload/pdf/kjp-36-4-257.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Ip, P.P.C.; Croce, S.; Bennett, J.A.; Garg, K.; Yang, B. Uterine Leiomyoma, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buza, N.; Quade, B.J. Intravenous Leiomyomatosis, 5th ed.; Oliva, E., Ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés Devesa, V.; Conley, C.R.; Stone, W.M.; Collins, J.M.; Magrina, J.F. Update on intravenous leiomyomatosis: Report of five patients and literature review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 171, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, H.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, K.S.; Shen, H.P.; Wu, P.J.; Tseng, C.J. Intravenous leiomyomatosis of the uterus: A clinicopathological analysis of nine cases and literature review. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 56, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Fu, J.; Cao, T.; Huang, L.; Qie, M.; Ouyang, Y. Clinicopathologic features and clinical outcomes of intravenous leiomyomatosis of the uterus: A case series. Medicine 2021, 100, e24228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Lu, B. Intravenous leiomyomatosis of the uterus: A clinicopathologic analysis of 13 cases with an emphasis on histogenesis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2018, 214, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canzonieri, V.; D’Amore, E.S.; Bartoloni, G.; Piazza, M.; Blandamura, S.; Carbone, A. Leiomyomatosis with vascular invasion. A unified pathogenesis regarding leiomyoma with vascular microinvasion, benign metastasizing leiomyoma and intravenous leiomyomatosis. Virchows Arch. 1994, 425, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhao, X.; Guo, D.; Li, H.; Sun, B. Intravenous leiomyomatosis of the uterus: A clinicopathologic study of 18 cases, with emphasis on early diagnosis and appropriate treatment strategies. Hum. Pathol. 2011, 42, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longacre, T.A.; Parra-Herran, C.; Lim, D. Uterine leiomyosarcoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours: Female Genital Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, P.P.C.; Croce, S.; Gupta, M. Smooth muscle tumour of uncertain malignant potential of the uterine corpus. In WHO Classification of Tumours: Female Genital Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-H.; Chiang, S. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours: Female Genital Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga, M.; Ushigome, S. Dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus with extrauterine extension. Histopathology 1998, 32, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, I.; Sinha, S.; Sinha, U.; Kumar, T.; Singh, J. Diffuse Leiomyomatosis of the Uterus: A Diagnostic Enigma. Cureus 2022, 14, e29595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrowski, R.; Babbel, B.; Fisch, D. Renal Calyceal Rupture following Ureteral Injury after Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2020, 9, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, E.M.; Bell, S.; Kamdar, N.S.; Swenson, C.W.; Wiese, H.; Morgan, D.M. Importance of Estimated Blood Loss in Resource Utilization and Complications of Hysterectomy for Benign Indications. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Age (Years) | Tumour Size (cm) | Presentation | Diagnostics | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Ghali et al., 2022 [18] 2 cases | 46 | 16 and 26 | Pelvic pain, menorrhagia and progressive abdominal distension and menorrhagia | MRI: solid and cystic, intermediate T2 intensity and high T2 intensity, areas of necrosis | Hysterectomy | Uneventful |

| Akkour et al., 2021 [19] | 32 | 33 | Abdominal distension, pelvic pain, suspicious for ovarian malignancy or leiomyosarcoma | MRI: cystic, huge abdomino-pelvic masses | Myomectomy | Intraoperative hemorrhage of 6L, blood transfusion, recovery uneventful |

| Erfani et al., 2024 [20] | 31 | 35 | Abdominal distension, suspicious for ovarian malignancy, elevated CA-125 levels | CT/MRI: inconclusive large pelvic tumour | Myomectomy | Not disclosed |

| Zou et al., 2024 [21] | 45 | 20 | Elevated CA-125, Pseudo-Meigs syndrome, suspicious for ovarian malignancy or leiomyosarcoma | CT: suspicion of ovarian malignancy, hydrothorax, ascites | Hysterectomy | Uneventful |

| Horta et al., 2015 [22] | 35 | 20 | Diffuse abdominal bloating | MRI: T2 hyperintense, cystic | Hysterectomy | Uneventful |

| Yamaguchi et al., 2024 [23] | 49 | 20 | Abdominal distension, suspicious for ovarian malignancy | MRI: T2 hyperintense, cystic, ovaries not sufficiently assessable | Hysterectomy | Uneventful |

| Lameira et al., 2022 [24] | 54 | 18 | Rapidly growing abdominal mass, suspicious for malignancy | MRI: T2 hyperintense, hydropic | Hysterectomy | Uneventful |

| Markers | Staining Pattern | Expression | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD34 | Membranous stain | Positive in vascular endothelial cells | Endothelial differentiation |

| D2-40 | Membranous stain | Positive in lymphatic endothelial cells | Lymphatic endothelial marker for the exclusion of lymphangiosis |

| Aktin | Cytoplasmic stain | Strongly positive | Expressed in tumours with myogenic differentiation; in endometrial stromal sarcoma only positive in areas of smooth muscle differentiation |

| Caldesmon | Cytoplasmic stain | Strongly positive | Expressed in tumours with myogenic differentiation; in endometrial stromal sarcoma only positive in areas of smooth muscle differentiation |

| Desmin | Cytoplasmic stain | Strongly positive | Expressed in tumours with myogenic differentiation; in endometrial stromal sarcoma only positive in areas of smooth muscle differentiation |

| CD10 | Diffuse cytoplasmic or membranous | Negative | Positive in endometrial stromal sarcoma (sensitivity 91%, specificity 45%) |

| Ki-67 | Nuclear stain | 1% | Very low proliferation index which indicates low tumour malignancy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie Freire, D.; Blumer, A.; Teixeira da Silva, T.; Düblin, S.; Diebold, J.; Fähnle-Schiegg, I. Multinodular Hydropic Leiomyoma in a 41-Year-Old Patient: A Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217615

Xie Freire D, Blumer A, Teixeira da Silva T, Düblin S, Diebold J, Fähnle-Schiegg I. Multinodular Hydropic Leiomyoma in a 41-Year-Old Patient: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217615

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie Freire, Diana, Alissia Blumer, Teresa Teixeira da Silva, Sonali Düblin, Joachim Diebold, and Ivo Fähnle-Schiegg. 2025. "Multinodular Hydropic Leiomyoma in a 41-Year-Old Patient: A Case Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217615

APA StyleXie Freire, D., Blumer, A., Teixeira da Silva, T., Düblin, S., Diebold, J., & Fähnle-Schiegg, I. (2025). Multinodular Hydropic Leiomyoma in a 41-Year-Old Patient: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217615