Using Classical Test Theory to Determine the Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Paediatric Feeding Disorder

1.2. Psychometrics

1.3. Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey

1.4. Aim of Study

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Protocol

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Structural Validity

3.3. Internal Consistency

3.4. Hypothesis Testing for Construct Validity

- (1)

- The hypothesis that there would be no significant difference in the impact of caregiver-related feeding and swallowing disorders on health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) between genders was supported by the Mann–Whitney U test. No significant differences between male (n = 33) and female caregivers (n = 76) were identified on the FS-IS-IT total score: Mean RankMale = 50.79 (Sum of Ranks = 1676.00); Mean RankFemale = 56.83 (Sum of Ranks = 4319.00); U = 1115.000; p = 0.359, two-tailed.

- (2)

- The hypothesis that the FS-IS-IT total score would not differ based on the gender of the child was confirmed, as no significant differences were found between boys (n = 51) and girls (n = 58): Mean RankMale = 54.58 (Sum of Ranks = 2783.50); Mean RankFemale = 55.37 (Sum of Ranks = 3211.50); U = 1457.500; p = 0.896, two-tailed.

- (3)

- The hypothesis that the FS-IS-IT total score would be associated with the IDDSI Functional Level score was supported (rs = −0.502, p < 0.001).

- (4)

- The hypothesis that the age of the children would not be associated with the FS-IS-IT total average score was confirmed (rs = −0.183, p = 0.60).

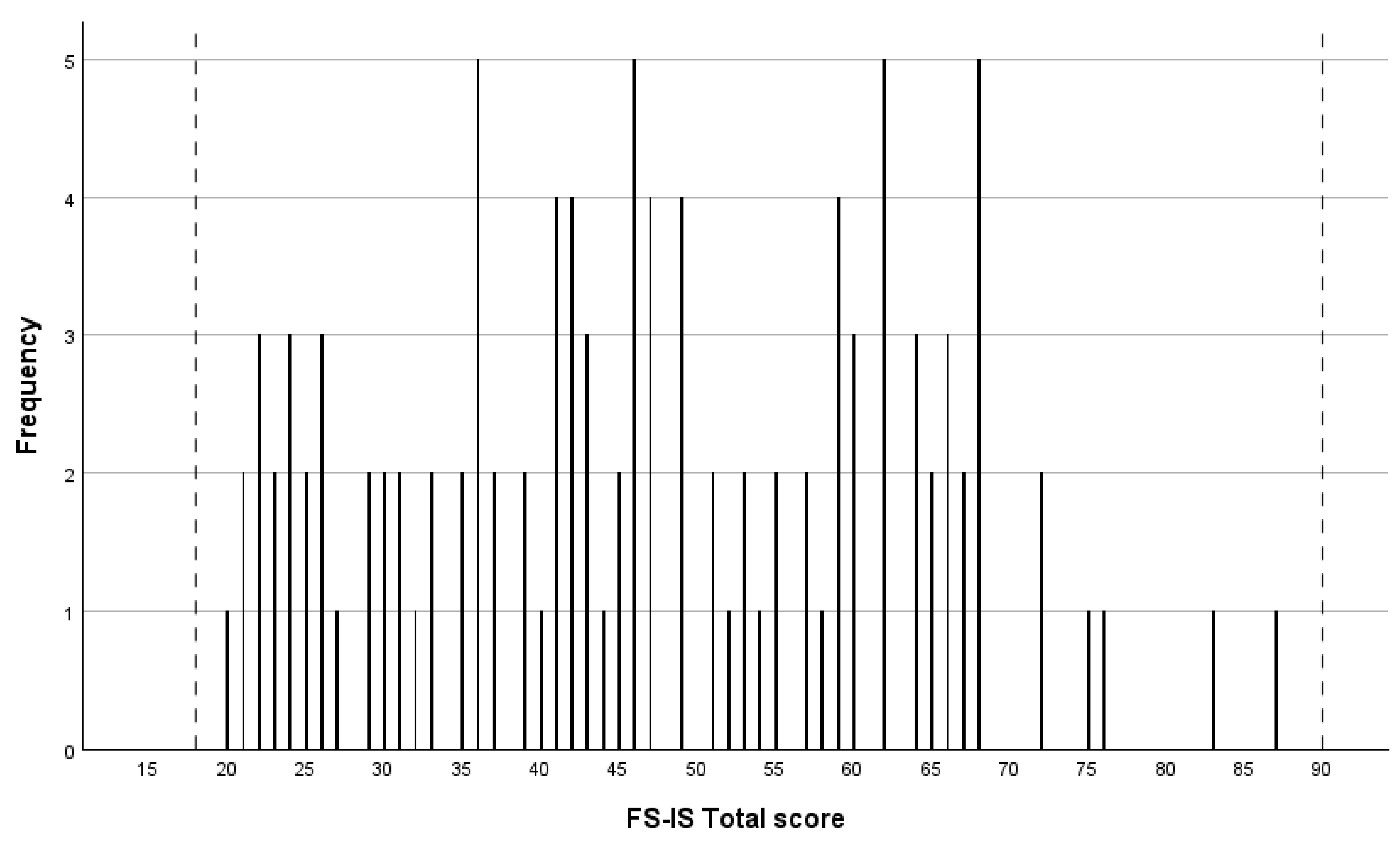

3.5. Interpretability

4. Discussion

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Future Research

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goday, P.S.; Huh, S.Y.; Silverman, A.; Lukens, C.T.; Dodrill, P.; Cohen, S.S.; Delaney, A.L.; Feuling, M.B.; Noel, R.J.; Gisel, E.; et al. Pediatric feeding disorder: Consensus definition and conceptual framework. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacic, K.; Rein, L.E.; Szabo, A.; Kommareddy, S.; Bhagavatula, P.; Goday, P.S. Pediatric feeding disorder: A nationwide prevalence study. J. Pediatr. 2021, 228, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrem, H.H.; Thoyre, S.M.; Knafl, K.A.; Frisk Pados, B.; Van Riper, M. “It’s a long-term process”: Description of daily family life when a child has a feeding disorder. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2017, 32, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, K.; Kristensson Hallstrom, I.; Landgren, K. Parents’ experiences of living with a child with Paediatric Feeding Disorder: An interview study in Sweden. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 37, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simione, M.; Dartley, A.N.; Cooper-Vince, C.; Martin, V.; Hartnick, C.; Taveras, E.M.; Fiechtner, L. Family-centered Outcomes that Matter Most to Parents: A Pediatric Feeding Disorders Qualitative Study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simione, M.; Harshman, S.; Cooper-Vince, C.E.; Daigle, K.; Sorbo, J.; Kuhlthau, K.; Fiechtner, L. Examining health conditions, impairments, and quality of life for pediatric feeding disorders. Dysphagia 2023, 38, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raatz, M.; Ward, E.C.; Marshall, J.; Afoakwah, C.; Byrnes, J. “It takes a whole day, even though it’s a one-hour appointment!” Factors impacting access to pediatric feeding services. Dysphagia 2020, 36, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefton-Greif, M.A.; Arvedson, J.C.; Farneti, D.; Levy, D.S.; Jadcherla, S.R. Global State of the art and science of childhood dysphagia: Similarities and disparities in burden. Dysphagia 2024, 39, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speyer, R. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: Screening and assessment. Otolaryngol. Clin. North. Am. 2013, 46, 989–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefton-Greif, M.A.; Okelo, S.O.; Wright, J.M.; Collaco, J.M.; McGrath-Morrow, S.A.; Eakin, M.N. Impact of children’s feeding/swallowing problems: Validation of a new caregiver instrument. Dysphagia 2014, 29, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, S.; Kılınç, H.; Yaşaroğlu, Ö.; İnal, Ö.; Demir, N.; Karaduman, A. Reliability and validity of the turkish version of the feeding/ swallowing impact survey. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2018, 6, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhlesin, M.; Ebadi, A.; Yadegari, F.; Ghoreishi, Z.S. Translation and Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey in Iranian Mothers. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2024, 76, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, C.G.; Bernardes, F.B.; Lefton-Greif, M.A.; Levy, D.S.; Bosa, V.L. Translation, Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validity Evidence of the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey (FS-IS) to Brazilian Portuguese. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 1226–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, G.; Rogers, E.; Kennedy, E.; Hemler, J.; Acra, S. A comparative analysis of eating behavior of School-Aged children with eosinophilic esophagitis and their caregivers’ quality of life: Perspectives of caregivers. Dysphagia 2019, 34, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.; Demir, N.; Karaduman, A.A.; Tanyel, F.C.; Soyer, T. Assessment of the concerns of caregivers of children with repaired esophageal Atresia-Tracheoesophageal fistula related to Feeding-Swallowing difficulties. Dysphagia 2020, 35, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S. Swallowing related problems of toddlers with down syndrome. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2023, 35, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracchia, M.S.; Diercks, G.; Yamasaki, A.; Hersh, C.; Hardy, S.; Hartnick, M.; Hartnick, C. Assessment of the feeding swallowing impact survey as a quality of life measure in children with laryngeal cleft before and after repair. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 99, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhoun, L.L.; Crerand, C.E.; O’Brien, M.; Baylis, A.L. Feeding and growth in infants with cleft lip and/or palate: Relationships with maternal distress. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2021, 58, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Hoeve, E.V.; Mustafa, A.; Lefton-Greif, M.A.; Ridout, D.; Smith, C.H. The Feeding-swallowing Impact Survey: Reference Values from a UK Sample of Parents of Children Without a Known or Suspected Feeding Disorder. Dysphagia 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffi, A.; Crispiatico, V.; Aiello, E.N.; Curti, B.; De Luca, G.; Poletti, B.; Montali, L. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Preliminary Validation of the Italian Version of the Feeding-Swallowing Impact Survey for both Members of Parental Dyads. Dysphagia 2025, 40, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, C.M.; Namasivayam-MacDonald, A.M.; Guida, B.T.; Cichero, J.A.; Duivestein, J.; Hanson, B.; Lam, P.; Riquelme, L.F. Creation and Initial Validation of the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative Functional Diet Scale. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichero, J.A.; Lam, P.T.; Chen, J.; Dantas, R.O.; Duivestein, J.; Hanson, B.; Kayashita, J.; Pillay, M.; Riquelme, L.F.; Steele, C.M.; et al. Release of updated International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative Framework (IDDSI 2.0). J. Texture Stud. 2020, 51, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlström, S.; Henning, I.; McGreevy, J.; Bergström, L. How Valid and Reliable Is the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) When Translated into Another Language? Dysphagia 2023, 38, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, C.; Giroux, A.; Villeneuve-Rhéaume, A.; Gagnon, C.; Germain, I. Is IDDSI an Evidence-Based Framework? A Relevant Question for the Frail Older Population. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; De Vet, H.C. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; Van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; De Vet, H.C.; Prinsen, C.A.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Boers, M.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. Risk of Bias tool to assess the quality of studies on reliability or measurement error of outcome measurement instruments: A Delphi study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J. Personal. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E. A Concise Guide to Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; William, C.B.; Barry, J.B.; Rolph, E.A. Multivariate Data Analysis. Cengage Learning; Andover: Hampshire, UK, 2018; p. 832. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vatcheva, K.P.; Lee, M.; McCormick, J.B.; Rahbar, M.H. Multicollinearity in Regression Analyses Conducted in Epidemiologic Studies. Epidemiology 2016, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Aryadoust, V.; Tan, H.A.H.; Ng, L.Y. A Scientometric review of Rasch measurement: The rise and progress of a specialty. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J. A User’s Guide to Winsteps Rasch-Model Computer Programs: Program Manual 3.92.0; Mesa-Press II: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Edelen, M.O.; Reeve, B.B. Applying item response theory (IRT) modeling to questionnaire development, evaluation, and refinement. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16 (Suppl. 1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n (%); Median (IQR) *; Range |

|---|---|

| Gender carer | |

| Male | 42 (31.3%) |

| Female | 92 (68.7%) |

| Age Carer (years) | Median 40.2 (IQR 34.0–45.0) Range: 25–66 |

| Work Activity | |

| Full-time | 79 (59.0%) |

| Part-time | 30 (22.4%) |

| Not working | 25 (18.6%) |

| Educational Level | |

| Secondary Education or lower | 67 (50.0%) |

| Tertiary Education | 67 (50.0%) |

| Child Gender | |

| Male | 66 (49.3%) |

| Female | 68 (50.7%) |

| Child Age (months) | Median 60.0 (IQR 35.8–108.0) Range: 2–164 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Congenital and genetic syndromes | 33 (24.6%) |

| Structural and craniofacial syndromes | 28 (20.9%) |

| Neurological and neurodevelopmental syndromes | 24 (17.9%) |

| Cerebral Palsy | 18 (13.4%) |

| Metabolic and endocrine syndromes | 13 (9.7%) |

| Muscular Dystrophies | 12 (9.0%) |

| Other diseases or disorders | 6 (4.5%) |

| IDDSI Functional Diet Scale (IDDSI-FDS) | Median 5.7 (IQR 5.0–7.0) Range: 0–8 |

| FS-IS Total Score ** | Median 46.9 (IQR 35.0–60.0) Range: 20–87 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.000 | 0.578 | 0.546 | 0.516 | 0.638 | 0.417 | 0.440 | 0.437 | 0.448 | 0.439 | 0.395 | 0.587 | 0.611 | 0.324 | 0.241 | 0.481 | 0.452 | 0.508 | 1 |

| n | 130 | 126 | 125 | 129 | 128 | 129 | 130 | 128 | 127 | 124 | 129 | 126 | 127 | 126 | 119 | 120 | 123 | 126 | n |

| 2 | - | 1.000 | 0.669 | 0.388 | 0.481 | 0.399 | 0.561 | 0.452 | 0.508 | 0.445 | 0.447 | 0.503 | 0.453 | 0.344 | 0.148 | 0.377 | 0.526 | 0.507 | 2 |

| n | - | 129 | 127 | 129 | 128 | 128 | 129 | 127 | 126 | 123 | 128 | 125 | 126 | 125 | 118 | 118 | 122 | 125 | n |

| 3 | - | - | 1.000 | 0.486 | 0.507 | 0.443 | 0.413 | 0.451 | 0.449 | 0.459 | 0.384 | 0.586 | 0.373 | 0.227 | 0.281 | 0.350 | 0.476 | 0.442 | 3 |

| n | - | - | 129 | 128 | 126 | 128 | 129 | 127 | 125 | 123 | 128 | 125 | 126 | 125 | 118 | 118 | 122 | 124 | n |

| 4 | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.557 | 0.320 | 0.356 | 0.380 | 0.373 | 0.475 | 0.518 | 0.519 | 0.427 | 0.318 | 0.130 | 0.452 | 0.422 | 0.313 | 4 |

| n | - | - | - | 133 | 131 | 132 | 133 | 131 | 129 | 126 | 132 | 129 | 130 | 129 | 122 | 121 | 126 | 128 | n |

| 5 | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.491 | 0.534 | 0.419 | 0.392 | 0.446 | 0.479 | 0.573 | 0.571 | 0.385 | 0.214 | 0.437 | 0.429 | 0.490 | 5 |

| n | - | - | - | - | 131 | 130 | 131 | 129 | 128 | 125 | 130 | 127 | 128 | 127 | 120 | 120 | 124 | 127 | n |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.511 | 0.379 | 0.342 | 0.515 | 0.465 | 0.328 | 0.472 | 0.298 | 0.257 | 0.453 | 0.419 | 0.455 | 6 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | 133 | 133 | 131 | 130 | 126 | 132 | 129 | 130 | 129 | 122 | 121 | 126 | 129 | n |

| 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.197 | 0.358 | 0.173 | 0.461 | 0.524 | 0.295 | 0.383 | 0.127 | 0.345 | 0.323 | 0.266 | 7 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | 134 | 132 | 130 | 127 | 133 | 130 | 131 | 130 | 123 | 122 | 127 | 129 | n |

| 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.079 | 0.268 | 0.247 | 0.210 | 0.210 | 0.221 | 0.060 | 0.186 | 0.224 | 0.256 | 8 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 132 | 129 | 127 | 131 | 129 | 130 | 129 | 122 | 121 | 126 | 128 | n |

| 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.083 | 0.283 | 0.255 | 0.157 | 0.232 | 0.130 | 0.195 | 0.170 | 0.091 | 9 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 130 | 126 | 130 | 127 | 128 | 127 | 120 | 120 | 124 | 128 | n |

| 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.230 | 0.177 | 0.264 | 0.291 | 0.269 | 0.368 | 0.326 | 0.402 | 10 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 127 | 127 | 125 | 126 | 125 | 118 | 118 | 122 | 124 | n |

| 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.730 | 0.465 | 0.515 | 0.060 | 0.375 | 0.383 | 0.372 | 11 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 133 | 130 | 131 | 130 | 123 | 122 | 126 | 128 | n |

| 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.504 | 0.491 | 0.141 | 0.407 | 0.363 | 0.296 | 12 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 130 | 129 | 128 | 122 | 120 | 124 | 126 | n |

| 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.492 | 0.111 | 0.450 | 0.389 | 0.332 | 13 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 131 | 129 | 123 | 121 | 124 | 127 | n |

| 14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.255 | 0.523 | 0.609 | 0.508 | 14 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 130 | 123 | 121 | 124 | 125 | n |

| 15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.357 | 0.270 | 0.279 | 15 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 123 | 115 | 119 | 119 | n |

| 16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.535 | 0.460 | 16 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 122 | 117 | 118 | n |

| 17 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.484 | 17 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 124 | n |

| 18 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | 18 |

| n | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 129 | n |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| Legend: | |||||||||||||||||||

| 0 ≤ r < 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 0.2 < r < 0.4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 0.4 < r < 0.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 0.6 < r < 0.8 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 0.8 < r ≤ 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crispiatico, V.; Baffi, A.; Buratti, M.A.; Montali, L.; Speyer, R. Using Classical Test Theory to Determine the Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217607

Crispiatico V, Baffi A, Buratti MA, Montali L, Speyer R. Using Classical Test Theory to Determine the Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217607

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrispiatico, Valeria, Alessandra Baffi, Mariagrazia Anna Buratti, Lorenzo Montali, and Renée Speyer. 2025. "Using Classical Test Theory to Determine the Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217607

APA StyleCrispiatico, V., Baffi, A., Buratti, M. A., Montali, L., & Speyer, R. (2025). Using Classical Test Theory to Determine the Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Feeding/Swallowing Impact Survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217607