Macitentan in the Treatment of Digital Ulcers in Patients with Systemic Rheumatic Autoimmune Diseases: A National Multicenter Study of 42 Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Ethical Concerns

3. Results

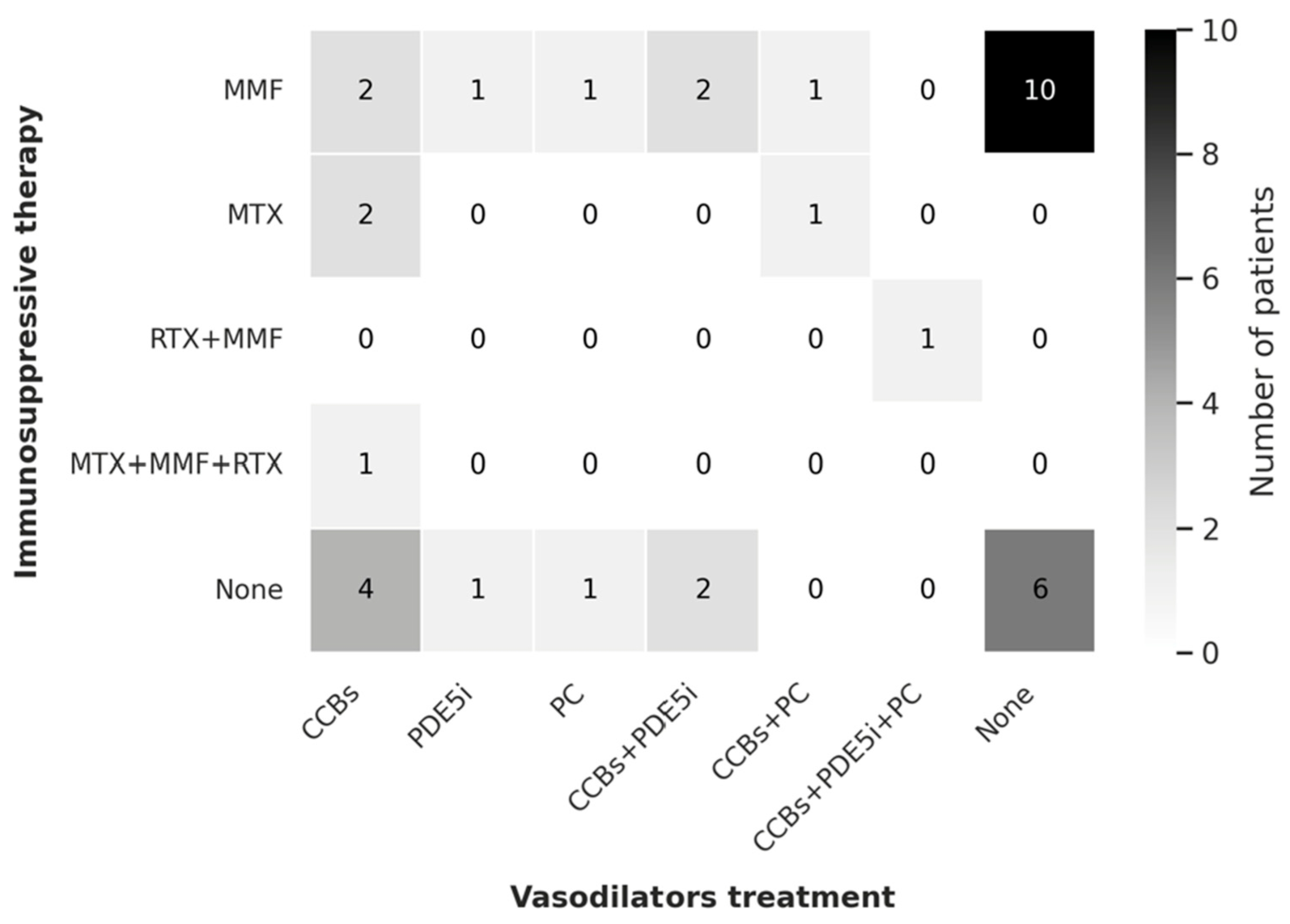

3.1. Previous Therapies and Treatment Regimens

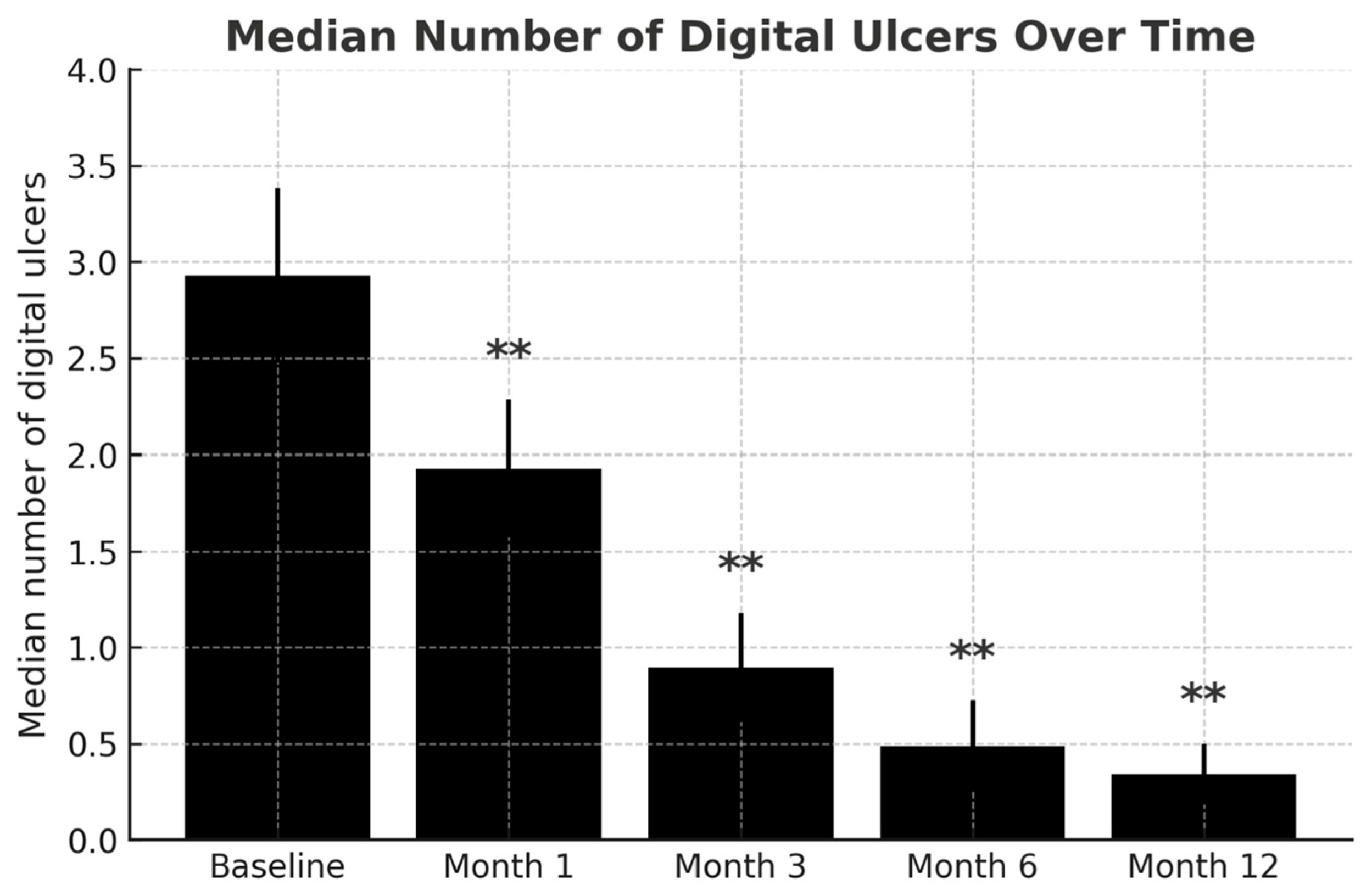

3.2. Efficacy Evaluation

3.3. Safety Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACA | anticentromere antibody |

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| AE | adverse event |

| APS | antiphospholipid syndrome |

| CCB | calcium channel blocker |

| DU | digital ulcer |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ERA | endothelin receptor antagonist |

| ET-1 | endothelin-1 |

| ETAR | endothelin receptor type A |

| ETBR | endothelin receptor type B |

| EULAR | European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology |

| EUSTAR | EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| MACI | macitentan |

| MMF | mycophenolate mofetil |

| PAH | pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| PC | intravenous prostacyclins |

| PDE5i | phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| RTX | rituximab |

| SARD | systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SSc | systemic sclerosis |

| UCTD | undifferentiated connective tissue disease |

| VEDOSS | very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis |

References

- Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Kahaleh, B.; Wigley, F.M. Review: Evidence that systemic sclerosis is a vascular disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Hughes, M.; Pauling, J.; Gooberman-Hill, R.; Moore, A.J. What narrative devices do people with systemic sclerosis use to describe the experience of pain from digital ulcers: A multicentre focus group study at UK scleroderma centres. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, C.P.; Khanna, D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescoat, A.; Huang, S.; Carreira, P.E.; Siegert, E.; de Vries-Bouwstraet, J.; Distler, J.H.W.; Smith, V.; Del Galdo, F.; Anic, B.; Damjanov, N.; et al. Cutaneous manifestations, clinical characteristics, and prognosis of patients with systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: Data from the international EUSTAR database. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisa, T.; Antonio, P.; Giuseppe, P.; Alessandro, B.; Giuseppe, A.; Federico, C.; Marzia, D.; Ruggero, B.; Giacomo, M.; Andrea, O.; et al. Endothelin receptors expressed by immune cells are involved in modulation of inflammation and in fibrosis: Relevance to the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 147616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Park, M.K.; Kim, H.Y.; Park, S.H. Capillary dimension measured by computer-based digitalized image correlated with plasma endothelin-1 levels in patients with systemic sclerosis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2010, 29, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, Y.; Eguchi, S.; Kanno, K.; Imai, T.; Ohta, K.; Marumo, F. Endothelin receptor subtype B mediates synthesis of nitric oxide by cultured bovine endothelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 91, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coral-Alvarado, P.; Quintana, G.; Garces, M.F.; Cepeda, L.A.; Caminos, J.E.; Rondon, F.; Iglesias-Gamarra, A.; Restrepo, J.F. Potential biomarkers for detecting pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol. Int. 2009, 29, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.; Delcroix, M.; Galié, N.; Jansa, P.; Mehta, S.; Pulido, T.; Rubin, L.; Sastry, B.K.S.; Simonneau, G.; Sitbon, O.; et al. Long-term safety, tolerability and survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension treated with macitentan: Results from the SERAPHIN open-label extension. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 4374–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemanse, J.; Sidharta, P.N.; Maddrey, W.C.; Rubin, L.J.; Mickail, H. Efficacy, safety and clinical pharmacology of macitentan in comparison to other endothelin receptor antagonists in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2014, 13, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Kotlyar, E.; Makanji, Y.; Yu, D.Y.; Tan, J.Y.; Casorso, J.; Kouhkamari, M.H.; Lim, S.; Wu, D.B.-C.; Bloomfield, P. Comparative adherence of macitentan versus ambrisentan and bosentan in Australian patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: A retrospective real-world database study. J. Med. Econ. 2024, 27, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidharta, P.N.; Lindegger, N.; Ulč, I.; Dingemanse, J. Pharmacokinetics of the novel dual endothelin receptor antagonist macitentan in subjects with hepatic or renal impairment. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 54, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepist, E.I.; Gillies, H.; Smith, W.; Hao, J.; Hubert, C.; Claire, R.L.S.; Brouwer, K.R.; Ray, A.S. Evaluation of the endothelin receptor antagonists ambrisentan, bosentan, macitentan, and sitaxsentan as hepatobiliary transporter inhibitors and substrates in sandwich-cultured human hepatocytes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA Approval Letter for Macitentan (Opsumit); US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, D.; Denton, C.P.; Merkel, P.A.; Krieg, T.; Le Brun, F.O.; Marr, A.; Papadakis, K.; Pope, J.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Furst, D.E. Effect of Macitentan on the development of new ischemic digital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis: DUAL-1 and DUAL-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA 2016, 315, 1975–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, Y. Is macitentan not a treatment option for digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis? Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4 (Suppl. S1), S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenzana, C.; Robles Marhuenda, Á.; Noblejas Mozo, A.; Soto Abánades, C.; Martínez Robles, E.; Rios Blancos, J.J. Macitentan for the treatment of severe digital ulcers in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease: Avoiding drug interactions. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Soto Abánades, C.; Noblejas Mozo, A.; Bonilla Hernán, G.; Alvarez Troncoso, J.; Ríos Blanco, J.J. Macitentan for the treatment of refractory digital ulcers in patients with connective tissue diseases. Cureus 2023, 15, e38303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.; Santos, L. Macitentan in the treatment of severe digital ulcers. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e228295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hoogen, F.; Khanna, D.; Fransen, J.; Johnson, S.R.; Baron, M.; Tyndall, A.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Naden, R.P.; Medsger, T.A., Jr.; Carreira, P.E.; et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellando-Randone, S.; Del Galdo, F.; Lepri, G.; Minier, T.; Huscher, D.; Furst, D.E.; Allanore, Y.; Distler, O.; Czirják, L.; Bruni, C.; et al. Progression of patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: A five-year analysis of the European Scleroderma Trial and Research group multicentre, longitudinal registry study for Very Early Diagnosis of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS). Lancet Rheumatol. 2021, 3, e834–e843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Krieg, T.; Guillevin, L.; Schwierin, B.; Rosenberg, D.; Cornelisse, P.; Denton, C.P. Elucidating the burden of recurrent and chronic digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: Long-term results from the DUO Registry. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrisroe, K.; Stevens, W.; Sahhar, J.; Ngian, G.S.; Ferdowsi, N.; Hill, C.L.; Roddy, J.; Walker, J.; Proudman, S.; Nikpour, M. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: Their epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and associated clinical and economic burden. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hoang, H.B.; Yang, J.Z.; Papamatheakis, D.G.; Poch, D.S.; Alotaibi, M.; Lombardi, S.; Rodriguez, C.; Kim, N.H.; Fernandes, T.M. Drug-Drug Interactions in the Management of Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Chest 2022, 162, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lorenzo-Pinto, A.; Pinilla Llorente, B. Successful Treatment with Bosentan for Digital Ulcers Related to Mixed Cryoglobulinemia: A Case Report. Am. J. Ther. 2016, 23, e1942–e1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltez, N.; Ross, L.; Baron, M.; Alunno, A.; Campochiaro, C.; Suliman, Y.A.; Schoones, J.W.; Allanore, Y.; Del Galdo, F.; Denton, C.P.; et al. Treatment recommendations for the systemic pharmacological treatment of systemic sclerosis digital ulcers: Results from the World Scleroderma Foundation Ad Hoc Committee. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n 42 | |

|---|---|

| Demographics Female, n (%) Age at MACI onset Age at onset of Raynaud’s, years Age at first DU diagnosis, years Time from first DU diagnosis to MACI, years | 33 (78.6) 64.1 (SD 11.4) 51.4 (SD 14.4) 57.5 (SD 13) 3 (1.1–10.9) |

| Disease classification Diffuse SSc, n (%) Limited SSc, n (%) VEDOSS, n (%) Other SARDs, n (%) | 6 (14.3) 31 (73.8) 2 (4.8) 3 (7.1) |

| Autoantibody Profile ANA positive, n (%) ACA positive, n (%) Anti-SCL-70 positive, n (%) Antiphospholipid ab positive, n (%) | 38 (90.5) 26 (61.9) 7 (16.7) 2 (4.8) |

| Smoking behavior Current, n (%) Former, n (%) | 7 (16.7) 11 (26.2) |

| DU count at baseline <5 ≥5–10 >10 Median total DU count | 30 (71.4) 9 (21.4) 3 (7.2) 2 (1–5) |

| DU localization—Hands only, n (%) | 31 (73.8) |

| Capillaroscopic features Cutolo “early” pattern Cutolo “active” pattern Cutolo “late” pattern Normal or non-specific | 11 (26.2) 9 (21.4) 16 (38.1) 6 (14.3) |

| PAH, n (%) | 1 (2.4) |

| Previous therapy Calcium antagonist PDE5 inhibitor Ambrisentan Bosentan Intravenous prostanoids Antibiotics Acetylsalicylic acid Amputation Surgical sympathectomy Systemic therapy | 39 (92.9) 20 (47.6) 3 (7.1) 40 (95.2) 19 (45.2) 15 (35.7) 22 (52.4) 7 (16.7) 3 (7.1) 23 (54.8) |

| Total Response n 30 | Partial/No Response n 6 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 25 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0.573 |

| dcSSc, n (%) | 25 (83.3) | 3 (50) | 0.109 |

| Mean total DU count | 2.2 (SD 2) | 6.3 (SD 4.6) | 0.028 |

| ANA, n (%) ACA, n (%) | 29 (96.7) 20 (66.6) | 6 (100) 3 (50) | 1 0.645 |

| Telangiectasias, n (%) | 22 (73.3) | 6 (100) | 0.302 |

| Calcinosis, n (%) | 20 (66.6) | 3 (50) | 0.645 |

| Joint involvement, n (%) | 8 (26.7) | 3 (50) | 0.343 |

| GI, n (%) | 14 (46.6) | 6 (100) | 0.022 |

| ILD, n (%) | 16 (53.3) | 3 (50) | 1 |

| Late capillar. pattern, n (%) | 11 (36.7) | 4 (66.7) | 0.367 |

| MACI mono (no vaso.), n (%) | 16 (53.3) | 5 (83.3) | 0.367 |

| CS use, n (%) | 8 (26.7) | 3 (50) | 0.343 |

| IS therapy, n (%) | 16 (53.3) | 3 (50) | 1 |

| Symp. and/or amput., n (%) | 3 (10) | 2 (33.3) | 0.180 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Retuerto-Guerrero, M.; Moriano Morales, C.; Castellvi Barranco, I.; Godoy Tundido, M.H.; Méndez Perles, C.; de la Puente Bujidos, C.; Pareja Martínez, A.S.; Garijo Bufort, M.; Riancho Zarrabeitia, L.; Aurrecoechea Aguinaga, E.; et al. Macitentan in the Treatment of Digital Ulcers in Patients with Systemic Rheumatic Autoimmune Diseases: A National Multicenter Study of 42 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217546

Retuerto-Guerrero M, Moriano Morales C, Castellvi Barranco I, Godoy Tundido MH, Méndez Perles C, de la Puente Bujidos C, Pareja Martínez AS, Garijo Bufort M, Riancho Zarrabeitia L, Aurrecoechea Aguinaga E, et al. Macitentan in the Treatment of Digital Ulcers in Patients with Systemic Rheumatic Autoimmune Diseases: A National Multicenter Study of 42 Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217546

Chicago/Turabian StyleRetuerto-Guerrero, Miriam, Clara Moriano Morales, Ivan Castellvi Barranco, María Hildegarda Godoy Tundido, Clara Méndez Perles, Carlos de la Puente Bujidos, Ana Salome Pareja Martínez, Marta Garijo Bufort, Leyre Riancho Zarrabeitia, Elena Aurrecoechea Aguinaga, and et al. 2025. "Macitentan in the Treatment of Digital Ulcers in Patients with Systemic Rheumatic Autoimmune Diseases: A National Multicenter Study of 42 Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217546

APA StyleRetuerto-Guerrero, M., Moriano Morales, C., Castellvi Barranco, I., Godoy Tundido, M. H., Méndez Perles, C., de la Puente Bujidos, C., Pareja Martínez, A. S., Garijo Bufort, M., Riancho Zarrabeitia, L., Aurrecoechea Aguinaga, E., González Arribas, G., Vicente-Rabaneda, E. F., Montes García, S., Atienza-Mateo, B., Calvo-Río, V., Corrales Selaya, C., Lorenzo Martín, J. A., & Díez Álvarez, E. (2025). Macitentan in the Treatment of Digital Ulcers in Patients with Systemic Rheumatic Autoimmune Diseases: A National Multicenter Study of 42 Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217546