Perceived Menstrual Irregularities and Premenstrual Syndrome in Relation to Insomnia: Evidence from a Cohort of Student Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Data Management and Statistical Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Menstrual Problems Frequency

3.3. Insomnia Frequency

3.4. Association Between Insomnia and Menstrual Problems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| AIS | Athens Insomnia Scale |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CAWI | Computer-Assisted Web Interview (web-based survey) |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| PMDD | Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder |

| PMS | Premenstrual Syndrome |

References

- Thomas, C.M.; McIntosh, C.E.; Lamar, R.A.; Allen, R.L. Sleep deprivation in nursing students: The negative impact for quality and safety. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binjabr, M.A.; Alalawi, I.S.; Alzahrani, R.A.; Albalawi, O.S.; Hamzah, R.H.; Ibrahim, Y.S.; Buali, F.; Husni, M.; BaHammam, A.S.; Vitiello, M.V.; et al. The worldwide prevalence of sleep problems among medical students by problem, country, and COVID-19 status: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 109 studies involving 59,427 participants. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2023, 9, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yu, T.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Yu, J. Poor sleep quality and overweight/obesity in healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1390643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Jang, K.-H.; Lim, H.-M.; Ahn, J.-S.; Park, W.-J. The menstrual cycle associated with insomnia in newly employed nurses performing shift work: A 12-month follow-up study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikura, I.; Fernandes, G.; Hachul, H.; Tufik, S.; Andersen, M. 0742 Is sleep altered during the menstrual cycle? A polysomnography study from EPISONO. Sleep 2023, 46, A326–A327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Fan, F.; Jia, C.-X. Early menarche and menstrual problems are associated with sleep disturbance in a large sample of Chinese adolescent girls. Sleep 2017, 40, zsx107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, G.E.; Han, K.; Lee, G. Association between sleep duration and menstrual cycle irregularity in Korean female adolescents. Sleep Med. 2017, 35, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.E.R.; Onyeonwu, C.; Nowakowski, S.; Hale, L.; Branas, C.C.; Killgore, W.D.S.; Wills, C.C.A.; Grandner, M.A. Menstrual regularity and bleeding is associated with sleep duration, sleep quality and fatigue in a community sample. J. Sleep Res. 2022, 31, e13434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbil, N.; Yücesoy, H. Relationship between premenstrual syndrome and sleep quality among nursing and medical students. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ge, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S. The association between occupational stress, sleep quality and premenstrual syndrome among clinical nurses. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, I.; Choi-Kwon, S.; Ki, J.; Kim, S.; Baek, J. Premenstrual Symptoms Risk Factors Among Newly Graduated Nurses in Shift Work: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Asian Nurs. Res. 2024, 18, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.-C.; Ko, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-J.; Yen, J.-Y. Insomnia, Inattention and Fatigue Symptoms of Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fornal-Pawłowska, M.; Wołończyk-Gmaj, D.; Szelenberger, W. Walidacja Ateńskiej Skali Bezsenności. Psychiatr. Pol. 2011, 45, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.; Xue, P.; Li, S.X.; Zhou, J.; Tang, X. Sleep disturbance is associated with an increased risk of menstrual problems in female Chinese university students. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, F.; Dong, H. The impact of chronic insomnia disorder on menstruation and ovarian reserve in childbearing-age women: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2024, 51, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, M.; Han, K.; Nam, G.E. The association between mental health problems and menstrual cycle irregularity among adolescent Korean girls. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, T. Premenstrual disorders: Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delray, K.; Lewis, G.; Hayes, J.F. Tracking mood symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women with depression using ecological momentary assessment and heart rate variability. BMJ Ment. Health 2025, 28, e301674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Diao, C.; Sun, J. Melatonin for premenstrual syndrome: A potential remedy but not ready. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 13, 1084249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shao, S.; Zhao, H.; Lu, Z.; Lei, X.; Zhang, Y. Circadian Rhythms Within the Female HPG Axis: From Physiology to Etiology. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqab117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vigil, P.; Meléndez, J.; Soto, H.; Petkovic, G.; Bernal, Y.A.; Molina, S. Chronic Stress and Ovulatory Dysfunction: Implications in Times of COVID-19. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 866104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baker, F.C.; Lee, K.A. Menstrual cycle effects on sleep. Sleep Med. Clin. 2022, 17, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Kim, H.; Koh, D.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Yoon, S. Relationship Between Shift Intensity and Insomnia Among Hospital Nurses in Korea: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2021, 54, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapkin, A.J.; Winer, S.A. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Quality of life and burden of illness. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2009, 9, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | PMS | Test | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Cycle regularity | yes | n (%) | 40 (78.4) | 18 (85.7) | Chi2 = 0.50, df = 1 | 0.48 |

| no | n (%) | 11 (21.6) | 3 (14.3) | |||

| Age | <25 | n (%) | 30 (58.8) | 13 (61.9) | Chi2 = 0.06, df = 1 | 0.81 |

| ≥25 | n (%) | 21 (41.2) | 8 (38.1) | |||

| Parity | no | n (%) | 38 (74.5) | 15 (71.4) | Chi2 = 0.07, df = 1 | 0.79 |

| yes | n (%) | 13 (25.5) | 6 (28.6) | |||

| Night shift work | no | n (%) | 14 (27.5) | 3 (14.3) | Chi2 = 1.42, df = 1 | 0.23 |

| yes | n (%) | 37 (72.6) | 18 (85.7) | |||

| Professional experience | no or <1 year | n (%) | 22 (43.1) | 5 (23.8) | Chi2 = 2.37, df = 1 | 0.30 |

| 1–5 years | n (%) | 16 (31.4) | 9 (42.7) | |||

| >5 years | n (%) | 13 (25.5) | 7 (33.3) | |||

| PMS | Z | p | ||||

| yes | no | |||||

| Body mass | [kg] | n | 51 | 21 | 0.10 | 0.92 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 62.0 (58.0–68.0) | 62.0 (57.0–68.0) | ||||

| Height | [cm] | n | 51 | 21 | 2.43 | 0.02 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 166.0 (164.0–170) | 164.0 (160.0–167.0) | ||||

| BMI | [kg/m2] | n | 51 | 21 | −0.95 | 0.34 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 22.2 (21.0–24.0) | 23.1 (21.5–26.5) | ||||

| Menarcheal age | [years] | n | 50 | 21 | −0.08 | 0.94 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 13.0 (12.0–14.0) | 13.0 (12.0–14.0) | ||||

| AIS | [total score] | n | 51 | 21 | 1.35 | 0.18 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 11.0 (8.0–13.0) | 8.0 (5.0–13.0) | ||||

| Item Score | N | PMS (Yes) | N | PMS (No) | Test | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Me (Q1–Q3) | Mean (SD) | Me (Q1–Q3) | |||||

| Sleep induction [0–3] | 51 | 1.24 (0.79) | 1.00 (1.0–2.0) | 21 | 1.24 (1.0) | 1.00 (0.0–2.0) | Z = 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Awakenings during the night [0–3] | 51 | 0.90 (0.73) | 1.00 (0.0–1.0) | 21 | 1.33 (0.9) | 1.00 (1.0–2.0) | Z = −1.94 | 0.05 |

| Final awakening earlier than desired [0–3] | 51 | 0.47 (0.73) | 0.00 (0.0–1.0) | 21 | 1.00 (1.0) | 1.00 (0.0–2.0) | Z = −2.31 | 0.02 |

| Total sleep duration [0–3] | 51 | 1.59 (0.78) | 2.00 (1.0–2.0) | 21 | 1.29 (0.6) | 1.00 (1.0–2.0) | Z = 2.14 | 0.03 |

| Overall quality of sleep [0–3] | 51 | 1.49 (0.67) | 2.00 (1.0–2.0) | 21 | 1.14 (0.9) | 1.00 (1.0–2.0) | Z = 1.74 | 0.08 |

| Sense of well-being during the day [0–3] | 51 | 1.57 (0.81) | 2.00 (1.0–2.0) | 21 | 1.00 (0.7) | 1.00 (1.0–1.0) | Z = 2.79 | 0.01 |

| Functioning during the day [0–3] | 51 | 1.45 (0.73) | 2.00 (1.0–2.0) | 21 | 0.62 (0.5) | 1.00 (0.0–1.0) | Z = 4.27 | 0.00 |

| Sleepiness during the day [0–3] | 51 | 1.88 (0.59) | 2.00 (2.0–2.0) | 21 | 1.38 (0.6) | 1.00 (1.0–2.0) | Z = 3.00 | 0.00 |

| AIS [total score] | 51 | 10.59 (3.69) | 11.00 (8.0–13.0) | 21 | 9.00 (4.7) | 8.00 (5.0–13.0) | t = 1.5, df = 70 | 0.13 |

| Outcome Measure | Insomnia Effect | Crude | p-Value | Adjusted | p-Value | AUC (SE) | Hosmer Lemeshow Test (HL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||||||

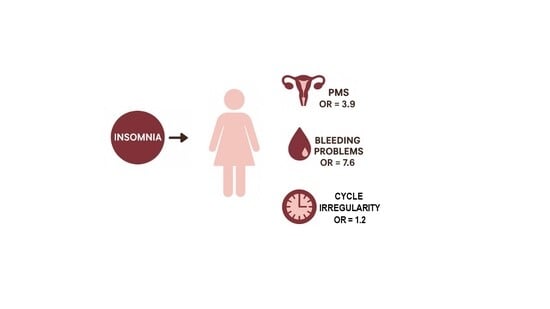

| PMS symptoms occurrence | AIS ≥ 8 points | 2.44 (0.83–7.18) | 0.11 | 3.93 (1.14–13.59) | 0.03 | 0.74 (0.07) | HL = 4.1; p = 0.85 |

| AIS total score | 1.11 (0.97–1.26) | 0.13 | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | 0.06 | 0.76 (0.07) | H-L = 9.4; p = 0.30 | |

| Cycle irregularity | AIS ≥ 8 points | 1.95 (0.49–7.74) | 0.34 | 3.00 (0.55–16.37) | 0.20 | 0.73 (0.07) | HL = 8.5; p = 0.39 |

| AIS total score | 1.10 (0.95–1.27) | 0.19 | 1.24 (1.01–1.50) | 0.04 | 0.77 (0.07) | H-L = 3.2; p = 0.92 | |

| Bleeding problems | AIS ≥ 8 points | 6.00 (1.34–26.81) | 0.02 | 7.56 (1.51–37-97) | 0.01 | 0.76 (0.10) | H-L = 8.1; p = 0.42 |

| AIS total score | 1.48 (1.15–1.91) | <0.001 | 1.51 (1.13–2.00) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.08) | H-L = 15.1; p = 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimlievych, A.; Dębska, G.; Grzesik-Gąsior, J.; Merklinger-Gruchala, A. Perceived Menstrual Irregularities and Premenstrual Syndrome in Relation to Insomnia: Evidence from a Cohort of Student Nurses. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217470

Dimlievych A, Dębska G, Grzesik-Gąsior J, Merklinger-Gruchala A. Perceived Menstrual Irregularities and Premenstrual Syndrome in Relation to Insomnia: Evidence from a Cohort of Student Nurses. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217470

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimlievych, Anastasiia, Grażyna Dębska, Joanna Grzesik-Gąsior, and Anna Merklinger-Gruchala. 2025. "Perceived Menstrual Irregularities and Premenstrual Syndrome in Relation to Insomnia: Evidence from a Cohort of Student Nurses" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217470

APA StyleDimlievych, A., Dębska, G., Grzesik-Gąsior, J., & Merklinger-Gruchala, A. (2025). Perceived Menstrual Irregularities and Premenstrual Syndrome in Relation to Insomnia: Evidence from a Cohort of Student Nurses. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217470