Secondary Prevention of AFAIS: Deploying Traditional Regression, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning Models to Validate and Update CHA2DS2-VASc for 90-Day Recurrence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. TRIPOD+AI Adherence

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Predictor Variables

2.5. Confounding Variables

2.6. Outcome Variables

2.7. Sample Size and Power Analysis

2.8. Handling Class Imbalance

2.9. Ethical Comment and Data Availability

2.10. Code Sharing

2.11. VISTA vs. the CHA2DS2-VASc Development Dataset

2.12. Statistical Analysis

2.12.1. Overview

2.12.2. Data Preprocessing

Missing Data Management Imputation

Imputation Diagnostics

Variable Encoding

2.12.3. Descriptive Statistics

2.12.4. Validation

| Questions | Hypotheses | Outcome Measures | Sampling Plan (N, Power Analyses) | Analysis Plan | Interpretation Given to Different Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary: How well does CHA2DS2-VASc capture 90-day AFAIS recurrence risk in terms of discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility? (Clinical utility performed against updated CPRs, see Tables 3 and 4.) Secondary: How well does CHA2DS2-VASc capture: 7-day recurrence, 7- and 90-day HT, 90-day decline in functional status, and 90-day all-cause mortality? Exploratory: How well does CHA2DS2-VASc capture 90-day recurrence and secondary outcomes for non-AF AIS patients? | Primary: Discrimination of CHA2DS2-VASc for 90-day AFAIS recurrence risk is unsatisfactory (AUC < 0.6), at worst, and modest (<0.7), at best. Calibration for 90-day recurrence also leaves much room for improvement. Secondary: As above. | Discrimination assessed using AUC and calibration curves. Calibration assessed using calibration curves, slopes, and Brier scores. Additional metrics: F1 score, accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, Youden index, PPV, NPR, PLR, NLR. | Primary: A minimum of 680 patients deemed necessary, see Appendix S5.3 in Supplementary Materials file S3. Entire AF dataset will be used, comprising 2763 AFAIS patients. Secondary: As above. Exploratory: Entire non-AF dataset will be used, comprising 7809 AIS patients. | Compute AUCs with 95% CIs using 1000 bootstrap replicates. Produce calibration curves (and report calibration slopes) to illustrate calibration. Calibration curves also serve as alternative to ROC curves, as they illustrate true and false positive rates across different risk thresholds and thus help visualise discrimination. Compute Brier scores. Compute additional metrics. | Discrimination for each outcome will be classified as follows [101]: AUC of 0.81–0.90 = good, 0.71–0.80= fair, 0.61–0.70 = modest, and 0.51–0.60 = poor. In practice, calibration is more vulnerable to geographic and temporal heterogeneity than discrimination [102,103,104,105]. We thus stress that calibration is at least as important as discrimination [77,102]. Clinical utility via DCA will go beyond discrimination and calibration, considering them both at the same time [106], as well as individual preferences. |

2.12.5. Updating

Models

Primary Analysis

Secondary Analysis

2.12.6. Regularisation

Multicollinearity

Regularisation Techniques

Hyperparameter Tuning

Model Building LR and XGBoost

MLP

Model Evaluation Test Set

Further Evalution of Primary Analysis Models

Model Interpretation

Local Interpretation

Global Interpretation

CPR Development

CPR Evaluation

External Validation

Fairness

Gender Bias

Age Bias

Comment on Ethnic and Socioeconomic Biases

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lopes, R.D.; Shah, B.R.; Olson, D.M.; Zhao, X.; Pan, W.; Bushnell, C.D.; Peterson, E.D. Antithrombotic therapy use at discharge and 1 year in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute stroke: Results from the AVAIL Registry. Stroke 2011, 42, 3477–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.Y.; Harrison, S.; Gupta, D.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Lane, D.A. Stroke and Bleeding Risk Assessments in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Concepts and Controversies. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, B.F.; Waterman, A.D.; Shannon, W.; Boechler, M.; Rich, M.W.; Radford, M.J. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: Results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001, 285, 2864–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Minematsu, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Japan Multicenter Stroke Investigators’ Collaboration (J-MUSIC). Atrial fibrillation as a predictive factor for severe stroke and early death in 15,831 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, C.; De Santis, F.; Sacco, S.; Russo, T.; Olivieri, L.; Totaro, R.; Carolei, A. Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: Results from a population-based study. Stroke 2005, 36, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, N.; Sheehan, O.; Kelly, L.; Marnane, M.; Merwick, A.; Moore, A.; Kyne, L.; Duggan, J.; Moroney, J.; McCormack, P.M.; et al. Stroke associated with atrial fibrillation—Incidence and early outcomes in the north Dublin population stroke study. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2010, 29, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelise, L.; Pinardi, G.; Morabito, A.; The Italian Acute Stroke Study Group. Mortality in acute stroke with atrial fibrillation. Stroke 1991, 22, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, N.; Daly, L.; Murphy, S.; Smith, S.; Hayden, D.; Chróinín, D.N.; Callaly, E.; Horgan, G.; Sheehan, Ó.; Honari, B.; et al. Acute hospital, community, and indirect costs of stroke associated with atrial fibrillation: Population-based study. Stroke 2014, 45, 3670–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, M.; Shantsila, E.; Lane, D.A.; Wolff, A.; Proietti, M.; Lip, G.Y.H. Secondary Versus Primary Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from the Darlington Atrial Fibrillation Registry. Stroke 2017, 48, 2198–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, A.H.; Kamel, H.; Healey, J.S.; Hart, R.G. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation: Looking Forward. Circulation 2020, 142, 2371–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, E.R.; Kapral, M.K.; Fang, J.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Conghaile, A.Ó.; Canavan, M.; O’dOnnell, M.J. Antithrombotic therapy after acute ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2014, 45, 3637–3642, Erratum in Stroke 2016, 47, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D.T.; Hannon, N.; Callaly, E.; Chróinín, D.N.; Horgan, G.; Kyne, L.; Duggan, J.; Dolan, E.; O’rOurke, K.; Williams, D.; et al. Rates and Determinants of 5-Year Outcomes After Atrial Fibrillation-Related Stroke: A Population Study. Stroke 2015, 46, 3488–3493, Erratum in Stroke 2015, 46, e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scowcroft, A.C.; Lee, S.; Mant, J. Thromboprophylaxis of elderly patients with AF in the UK: An analysis using the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) 2000–2009. Heart 2013, 99, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Piccini, J.P.; Hernandez, A.F.; Zhao, X.; Patel, M.R.; Lewis, W.R.; Peterson, E.D.; Fonarow, G.C. Quality of care for atrial fibrillation among patients hospitalized for heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.D.; Starr, A.; Pieper, C.F.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Newby, L.K.; Mehta, R.H.; Van de Werf, F.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Armstrong, P.W.; Harrington, R.A.; et al. Warfarin use and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation complicating acute coronary syndromes. Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamiri, N.; Eikelboom, J.; Reilly, P.; Ezekowitz, M.; Oldgren, J.; Yusuf, S.; Connolly, S. CHA2DS2-VASC versus HAS-BLED score for predicting risk of major bleeding and ischemic stroke in atrial fibrillation: Insights from RE-LY trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.G.; Pearce, L.A.; Aguilar, M.I. Meta-analysis: Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group. Independent predictors of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review. Neurology 2007, 69, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Zhao, X.Q.; Wang, C.X.; Liu, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. One-year clinical prediction in Chinese ischemic stroke patients using the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores: The China National Stroke Registry. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012, 18, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, I.; Song, T.J.; Kim, B.J.; Heo, S.H.; Jung, J.-M.; Oh, K.-M.; Kim, C.K.; Yu, S.; Park, K.Y.; Kim, J.-M.; et al. CHADS2, CHA2DS2-VASc, ATRIA, and Essen stroke risk scores in stroke with atrial fibrillation: A nationwide multicenter registry study. Medicine 2021, 100, e24000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.B.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Hansen, M.L.; Hansen, P.R.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Lindhardsen, J.; Selmer, C.; Ahlehoff, O.; Olsen, A.-M.S.; Gislason, G.H.; et al. Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2011, 342, d124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, K.M.; Farahmand, B.; Johansson, S.; Asberg, S.; Terént, A.; Edvardsson, N. Survival after stroke—The impact of CHADS2 score and atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 141, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Tran, G.; Genaidy, A.; Marroquin, P.; Estes, C.; Landsheft, J. Improving dynamic stroke risk prediction in non-anticoagulated patients with and without atrial fibrillation: Comparing common clinical risk scores and machine learning algorithms. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2022, 8, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHA2DS2-VASc Score for Atrial Fibrillation Stroke Risk. Available online: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/801/cha2ds2-vasc-score-atrial-fibrillation-stroke-risk (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Furie, K.L.; Khan, M. Secondary Prevention of Cardioembolic Stroke. In Elsevier eBooks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1014–1029.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, e364–e467, Erratum in Stroke 2021, 52, e483–e484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, D.; Abdul-Rahim, A.H.; Fischer, U.; Werring, D.J.; Robinson, T.G.; Dawson, J. A survey of opinion: When to start oral anticoagulants in patients with acute ischaemic stroke and atrial fibrillation? Eur. Stroke J. 2018, 3, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.D.; Alexander, J.H.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Ansell, J.; Diaz, R.; Easton, J.D.; Gersh, B.J.; Granger, C.B.; Hanna, M.; Horowitz, J.; et al. Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other ThromboemboLic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial: Design and rationale. Am. Heart J. 2010, 159, 331–339, Erratum in Am. Heart J. 2010, 159, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.R.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Garg, J.; Pan, G.; Singer, D.E.; Hacke, W.; Breithardt, G.; Halperin, J.L.; Hankey, G.J.; Piccini, J.P.; et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, C.W.; Lip, G.Y. Insights from the dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation (RE-LY) trial. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2010, 11, 685–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, U.; Koga, M.; Strbian, D.; Branca, M.; Abend, S.; Trelle, S.; Paciaroni, M.; Thomalla, G.; Michel, P.; Nedeltchev, K.; et al. Early versus Later Anticoagulation for Stroke with Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldgren, J.; Åsberg, S.; Hijazi, Z.; Wester, P.; Bertilsson, M.; Norrving, B. Early versus Delayed Non–Vitamin K Antagonist oral anticoagulant therapy after Acute ischemic Stroke in atrial fibrillation (TIMING): A Registry-Based randomized controlled noninferiority study. Circulation 2022, 146, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchis, G.M.; Seiffge, D.J.; Schaedelin, S.; Wilson, D.; Caso, V.; Acciarresi, M.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Koga, M.; Yoshimura, S.; Toyoda, K.; et al. Early versus late start of direct oral anticoagulants after acute ischaemic stroke linked to atrial fibrillation: An observational study and individual patient data pooled analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 93, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.G.; Arram, L.; Ahmed, N.; Balogun, M.; Bennett, K.; Bordea, E.; Campos, M.G.; Caverly, E.; Chau, M.; Cohen, H.; et al. Optimal timing of anticoagulation after acute ischemic stroke with atrial fibrillation (OPTIMAS): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Stroke 2022, 17, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffge, D.J.; Werring, D.J.; Paciaroni, M.; Dawson, J.; Warach, S.; Milling, T.J.; Engelter, S.T.; Fischer, U.; Norrving, B. Timing of anticoagulation after recent ischaemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, G.; Gallego, B. Clinical prediction rules: A systematic review of healthcare provider opinions and preferences. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 123, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plüddemann, A.; Wallace, E.; Bankhead, C.; Keogh, C.; Van der Windt, D.; Lasserson, D.; Galvin, R.; Moschetti, I.; Kearley, K.; O’brien, K.; et al. Clinical prediction rules in practice: Review of clinical guidelines and survey of GPs. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2014, 64, e233–e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damen, J.A.A.G.; Hooft, L.; Schuit, E.; Debray, T.P.A.; Collins, G.S.; Tzoulaki, I.; Lassale, C.M.; Siontis, G.C.M.; Chiocchia, V.; Roberts, C.; et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: Systematic review. BMJ 2016, 353, i2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynants, L.; Van Calster, B.; Collins, G.S.; Riley, R.D.; Heinze, G.; Schuit, E.; Bonten, M.M.J.; Dahly, D.L.; Damen, J.A.; Debray, T.P.A.; et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19: Systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 2020, 369, m1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouli, M.; Friedman, P.A. Ischemic Stroke Risk in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 3050–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.S.; Lin, C.L. Use of CHA2DS2-VASc Score to Predict New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients—Large-Scale Longitudinal Study. Circ. J. 2017, 81, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camm, A.J.; Lip, G.Y.H.; De Caterina, R.; Savelieva, I.; Atar, D.; Hohnloser, S.H.; Hindricks, G.; Kirchhof, P.; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); Bax, J.J.; et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2719–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toll, D.B.; Janssen, K.J.; Vergouwe, Y.; Moons, K.G. Validation, updating and impact of clinical prediction rules: A review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwmeester, W.; Zuithoff, N.P.; Mallett, S.; I Geerlings, M.; Vergouwe, Y.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G.M. Reporting and methods in clinical prediction research: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laupacis, A.; Sekar, N.; Stiell, I.G. Clinical prediction rules. A review and suggested modifications of methodological standards. JAMA 1997, 277, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS); American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR); Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE); Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (CIRA); Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS); European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT); European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR); European Stroke Organization (ESO); Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI); Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR); et al. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Revised Consensus Statement for Endovascular Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Int. J. Stroke 2018, 13, 612–632. [Google Scholar]

- Steyerberg, E.W.; Moons, K.G.; van der Windt, D.A.; Hayden, J.A.; Perel, P.; Schroter, S.; Riley, R.D.; Hemingway, H.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 3: Prognostic model research. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaur Navarro, C.L.; Damen, J.A.A.; Takada, T.; Nijman, S.W.J.; Dhiman, P.; Ma, J.; Collins, G.S.; Bajpai, R.; Riley, R.D.; Moons, K.G.M.; et al. Completeness of reporting of clinical prediction models developed using supervised machine learning: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2022, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, M.M.; de Macedo Filho, L.; White, A.J.; Perez-Vega, C.; Samson, S.L.; Chaichana, K.L.; Olomu, O.U.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Almeida, J.P. Machine Learning Models to Forecast Outcomes of Pituitary Surgery: A Systematic Review in Quality of Reporting and Current Evidence. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munguía-Realpozo, P.; Etchegaray-Morales, I.; Mendoza-Pinto, C.; Méndez-Martínez, S.; Osorio-Peña, Á.D.; Ayón-Aguilar, J.; García-Carrasco, M. Current state and completeness of reporting clinical prediction models using machine learning in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, O.T.; Harun, H.; Mustafa, N.; Murad, N.A.A.; Chin, S.F.; Jaafar, R.; Abdullah, N. Cardiovascular complications in a diabetes prediction model using machine learning: A systematic review. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Yang, Z.; Hou, M.; Shi, X. Machine learning in predicting cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 951881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Fan, X.; Cao, X.; Hao, W.; Lu, J.; Wei, J.; Tian, J.; Yin, M.; Ge, L. Reporting and risk of bias of prediction models based on machine learning methods in preterm birth: A systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groot, O.Q.; Ogink, P.T.; Lans, A.; Twining, P.K.; Kapoor, N.D.; DiGiovanni, W.; Bindels, B.J.J.; Bongers, M.E.R.; Oosterhoff, J.H.F.; Karhade, A.V.; et al. Machine learning prediction models in orthopedic surgery: A systematic review in transparent reporting. J. Orthop. Res. 2022, 40, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lans, A.; Kanbier, L.N.; Bernstein, D.N.; Groot, O.Q.; Ogink, P.T.; Tobert, D.G.; Verlaan, J.; Schwab, J.H. Social determinants of health in prognostic machine learning models for orthopaedic outcomes: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2023, 29, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Feridooni, T.; Cuen-Ojeda, C.; Kishibe, T.; de Mestral, C.; Mamdani, M.; Al-Omran, M. Machine learning in vascular surgery: A systematic review and critical appraisal. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, O.Q.; Bindels, B.J.J.; Ogink, P.T.; Kapoor, N.D.; Twining, P.K.; Collins, A.K.; Bongers, M.E.R.; Lans, A.; Oosterhoff, J.H.F.; Karhade, A.V.; et al. Availability and reporting quality of external validations of machine-learning prediction models with orthopedic surgical outcomes: A systematic review. Acta Orthop. 2021, 92, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaur Navarro, C.L.; Damen, J.A.A.; Takada, T.; Nijman, S.W.J.; Dhiman, P.; Ma, J.; Collins, G.S.; Bajpai, R.; Riley, R.D.; Moons, K.G.M.; et al. Risk of bias in studies on prediction models developed using supervised machine learning techniques: Systematic review. BMJ 2021, 375, n2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, E.; Ma, J.; Collins, G.S.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Van Calster, B. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 110, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.; Atal, I.; Li, J.; Smith, P.; Ravaud, P.; Fergie, M.; Callaghan, M.; Selfe, J. Reporting quality of studies using machine learning models for medical diagnosis: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kiik, M.; Peek, N.; Curcin, V.; Marshall, I.J.; Rudd, A.G.; Wang, Y.; Douiri, A.; Wolfe, C.D.; Bray, B. A systematic review of machine learning models for predicting outcomes of stroke with structured data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.; Turner, J.; Jacques, R.; Williams, J.; Mason, S. Using machine learning risk prediction models to triage the acuity of undifferentiated patients entering the emergency care system: A systematic review. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2020, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, P.; Ma, J.; Navarro, C.A.; Speich, B.; Bullock, G.; Damen, J.A.; Kirtley, S.; Hooft, L.; Riley, R.D.; Van Calster, B.; et al. Reporting of prognostic clinical prediction models based on machine learning methods in oncology needs to be improved. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 138, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD Statement. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppe, A.; Skrede, O.J.; De Raedt, S.; Liestøl, K.; Kerr, D.J.; Danielsen, H.E. Designing deep learning studies in cancer diagnostics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korevaar, D.A.; Hooft, L.; Askie, L.M.; Barbour, V.; Faure, H.; Gatsonis, C.A.; E Hunter, K.; Kressel, H.Y.; Lippman, H.; McInnes, M.D.F.; et al. Facilitating prospective registration of diagnostic accuracy Studies: A STARD initiative. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. The importance of predefined rules and prespecified statistical analyses. JAMA 2019, 321, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppe, A.; Skrede, O.J.; Liestøl, K.; Kerr, D.J.; Danielsen, H.E. Guidelines for study protocols describing predefined validations of prediction models in medical deep learning and beyond. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, P.; Whittle, R.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; McCradden, M.D.; Moons, K.G.M.; Riley, R.D.; Collins, G.S. The TRIPOD-P reporting guideline for improving the integrity and transparency of predictive analytics in healthcare through study protocols. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 816–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, W.; Gronich, N.; Barnett-Griness, O.; Rennert, G. The role of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-ASc scores in the prediction of stroke in individuals without atrial fibrillation: A population-based study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, A.S.; Hylek, E.M.; Phillips, K.A.; Chang, Y.; Henault, L.E.; Selby, J.V.; Singer, D.E. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: National implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: The AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001, 285, 2370–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Induruwa, I.; Amis, E.; Hannon, N.; Khadjooi, K. The increasing burden of atrial fibrillation in acute medical admissions, an opportunity to optimise stroke prevention. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2017, 47, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiin, G.S.; Howard, D.P.; Paul, N.L.; Li, L.; Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Bull, L.M.; Welch, S.J.; Gutnikov, S.A.; Mehta, Z.; Rothwell, P.M. Age-specific incidence, outcome, cost, and projected future burden of atrial fibrillation-related embolic vascular events: A population-based study. Circulation 2014, 130, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, P.J. Preventing the rise of atrial fibrillation-related stroke in populations: A call to action. Circulation 2014, 130, 1221–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, C.; Jenkins, D.; Martin, G.P.; Kontopantelis, E.; Body, R. Is your clinical prediction model past its sell by date? Emerg. Med. J. 2022, 39, 956–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Wynants, L.; Van Smeden, M. There is no such thing as a validated prediction model. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steyerberg, E.W. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Bath, P.M.; Curram, J.; Davis, S.M.; Diener, H.-C.; Donnan, G.A.; Fisher, M.; Gregson, B.A.; Grotta, J.; Hacke, W.; et al. The Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive. Stroke 2007, 38, 1905–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimar, C.; Ali, M.; Lees, K.R.; Bluhmki, E.; Donnan, G.A.; Diener, H.C. The Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive (VISTA): Results and impact on future stroke trials and management of stroke patients. Int. J. Stroke 2010, 5, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, M.; De Groot, J.A.H.; Moons, K.G.M.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Reitsma, J.B. No rationale for 1 variable per 10 events criterion for binary logistic regression analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, M.; Moons, K.G.; de Groot, J.A.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Reitsma, J.B. Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2019, 28, 2455–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.D.; Snell, K.I.; Ensor, J.; Burke, D.L.; Harrell, F.E., Jr.; Moons, K.G.M.; Collins, G.S. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II—binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 1276–1296, Erratum in Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.D.; Ensor, J.; Snell, K.I.E.; Harrell, F.E.; Martin, G.P.; Reitsma, J.B.; Moons, K.G.M.; Collins, G.; van Smeden, M. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 2020, 368, m441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, T.; Austin, P.C.; Steyerberg, E.W. Modern modelling techniques are data hungry: A simulation study for predicting dichotomous endpoints. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hond, A.A.H.; Leeuwenberg, A.M.; Hooft, L.; Kant, I.M.J.; Nijman, S.W.J.; Van Os, H.J.A.; Aardoom, J.J.; Debray, T.P.A.; Schuit, E.; van Smeden, M.; et al. Guidelines and quality criteria for artificial intelligence-based prediction models in healthcare: A scoping review. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, H.; Hoyle, D.C.; Singh, S. Machine learning in bioinformatics: A brief survey and recommendations for practitioners. Comput. Biol. Med. 2006, 36, 1104–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, E.; van Smeden, M.; Edlinger, M.; Timmerman, D.; Wanitschek, M.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Van Calster, B. Adaptive sample size determination for the development of clinical prediction models. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2021, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahri, Y.; Dyer, E.; Kaplan, J.; Lee, J.; Sharma, U. Explaining neural scaling laws. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, 8121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthery, F.S.; Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. J. Wildl. Manag. 2003, 67, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Capucci, A.; Lip, G.Y.; Olsson, S.B.; Prins, M.H.; Nieman, F.H.; López-Sendón, J.; Vardas, P.E.; Aliot, E.; Santini, M.; et al. Antithrombotic treatment in real-life atrial fibrillation patients: A report from the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 3018–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.; Nieuwlaat, R.; Pisters, R.; Lane, D.A.; Crijns, H.J. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010, 137, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doove, L.L.; Van Buuren, S.; Dusseldorp, E. Recursive partitioning for missing data imputation in the presence of interaction effects. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2014, 72, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azur, M.J.; Stuart, E.A.; Frangakis, C.; Leaf, P.J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 20, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.M.; Schafer, J.L.; Kam, C.M. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol. Methods 2001, 6, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.L. Multiple imputation in multivariate problems when the imputation and analysis models differ. Stat. Neerl. 2003, 57, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.W. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbakel, J.Y.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Uno, H.; De Cock, B.; Wynants, L.; Collins, G.S.; Van Calster, B. ROC curves for clinical prediction models part 1. ROC plots showed no added value above the AUC when evaluating the performance of clinical prediction models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 126, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, K.G.; Altman, D.G.; Reitsma, J.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Macaskill, P.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Vickers, A.J.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Collins, G.S. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, W1–W73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovani, D.; Sokou, R.; Tsantes, A.G.; Vitello, A.S.; Bonovas, S. Optimizing Clinical Decision Making with Decision Curve Analysis: Insights for Clinical Investigators. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, T.J.; Usman, M.S.; Shahid, I.; Ahmed, J.; Khan, S.U.; Ya’qoub, L.; Rihal, C.S.; Alkhouli, M. Utility of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for predicting ischaemic stroke in patients with or without atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B.; McLernon, D.J.; van Smeden, M.; Wynants, L.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Topic Group ‘Evaluating diagnostic tests and prediction models’ of the STRATOS initiative. Calibration: The Achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, G.; Upshaw, J.; Wessler, B.S.; Brazil, R.J.; Nelson, J.; van Klaveren, D.; Lundquist, C.M.; Park, J.G.; McGinnes, H.; Steyerberg, E.W.; et al. Generalizability of Cardiovascular Disease Clinical Prediction Models: 158 Independent External Validations of 104 Unique Models. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 15, e008487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijken, K.; Groenwold, R.H.H.; Van Calster, B.; Steyerberg, E.W.; van Smeden, M. Impact of predictor measurement heterogeneity across settings on the performance of prediction models: A measurement error perspective. Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 3444–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C.; van Klaveren, D.; Vergouwe, Y.; Nieboer, D.; Lee, D.S.; Steyerberg, E.W. Validation of prediction models: Examining temporal and geographic stability of baseline risk and estimated covariate effects. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2017, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B.; Vickers, A.J. Calibration of risk prediction models: Impact on decision-analytic performance. Med. Decis. Mak. 2015, 35, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, D.J. Classifier technology and the illusion of progress. Stat. Sci. 2006, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbehoj, A.; Thunbo, M.Ø.; Andersen, O.E.; Glindtvad, M.V.; Hulman, A. Transfer learning for non-image data in clinical research: A scoping review. PLOS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuwenberg, A.M.; Maarten, V.S.; Langendijk, J.A.; Arjen, V.D.S.; Mauer, M.E.; Moons, K.G.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Schuit, E. Comparing methods addressing multi-collinearity when developing prediction models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.01603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar, D.E.; Glauber, R.R. Multicollinearity in Regression Analysis: The problem revisited. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1967, 49, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggensperger, K.; Lindauer, M.; Hutter, F. Pitfalls and best practices in algorithm configuration. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.06058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, T.; Mukaino, M.; Matsunaga, K.; Wada, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Aoshima, Y.; Furuzawa, S.; Kono, Y.; Saitoh, E.; Yamaguchi, M.; et al. Prediction of stroke patients’ bedroom-stay duration: Machine-learning approach using wearable sensor data. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 1285945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Ong, M.E.H.; Chakraborty, B.; Goldstein, B.A.; Ting, D.S.W.; Vaughan, R.; Liu, N. Shapley variable importance cloud for interpretable machine learning. Patterns 2022, 3, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimbi, V.; Shaffi, N.; Mahmud, M. Interpreting artificial intelligence models: A systematic review on the application of LIME and SHAP in Alzheimer’s disease detection. Brain Inform. 2024, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covert, I.; Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. Understanding global feature contributions with additive importance measures. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 17212–17223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.E. Can you Open a Box Without Touching It? Circumventing the Black Box of Artificial Intelligence to Reconcile Algorithmic Opacity and Ethical Soundness. In Social, Ethical, and Cultural Aspects of the Use of Artificial Intelligence. The Future of New Technologies; Polish Economic Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ustun, B.; Rudin, C. Supersparse linear integer models for optimized medical scoring systems. Mach. Learn. 2015, 102, 349–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Roger, V.L.; Redfield, M.M. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewington, S.; Clarke, R.; Qizilbash, N.; Peto, R.; Collins, R.; Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002, 360, 1903–1913, Erratum in Lancet 2002, 361, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowers, J.R.; Epstein, M.; Frohlich, E.D. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: An update. Hypertension 2001, 37, 1053–1059, Erratum in Hypertension 2001, 37, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B.; Wynants, L.; Verbeek, J.F.M.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Christodoulou, E.; Vickers, A.J.; Roobol, M.J.; Steyerberg, E.W. Reporting and Interpreting Decision Curve Analysis: A Guide for Investigators. Eur. Urol. 2018, 74, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siontis, G.C.; Tzoulaki, I.; Castaldi, P.J.; Ioannidis, J.P. External validation of new risk prediction models is infrequent and reveals worse prognostic discrimination. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 68, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.B.; Skjøth, F.; Overvad, T.F.; Larsen, T.B.; Lip, G.Y.H. Female Sex Is a Risk Modifier Rather Than a Risk Factor for Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation: Should We Use a CHA2DS2-VA Score Rather Than CHA2DS2-VASc? Circulation 2018, 137, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, U.R.; Kim, N.; Magnani, J.W.; Good, C.B.; Litam, T.M.A.; Hausmann, L.R.M.; Mor, M.K.; Gellad, W.F.; Fine, M.J. Association of Race and Ethnicity and Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Dually Enrolled in Veterans Health Administration and Medicare: Effects of Medicare Part D on Prescribing Disparities. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 15, e008389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kist, J.M.; Vos, R.C.; Mairuhu, A.T.A.; Struijs, J.N.; van Peet, P.G.; Vos, H.M.; van Os, H.J.; Beishuizen, E.D.; Sijpkens, Y.W.; Faiq, M.A.; et al. SCORE2 cardiovascular risk prediction models in an ethnic and socioeconomic diverse population in the Netherlands: An external validation study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Hyperparameter | Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LR | C (L2 regularisation strength) | [0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100] | |

| max_iter | [100, 200, 500] | ||

| XGBoost | n_estimators | [50, 100, 200] | |

| learning_rate | [0.01, 0.1, 0.2] | ||

| max_depth | [3, 5, 7, 9] | ||

| MLP | Pretraining | units (hidden layer sizes) | [32, 64, 128, 256, 512] |

| hidden_layers | [1, 2, 3, 4] | ||

| activation | [‘relu’, ‘tanh’] | ||

| learning_rate | [0.0001, 0.001, 0.01] | ||

| kernel_regularizer = l2() | [0.000001, 0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1] | ||

| dropout (dropout rate) | [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5] | ||

| Fine-tuning | units (hidden layer sizes) | [32, 64, 128, 256, 512] | |

| hidden_layers | [1, 2, 3, 4] | ||

| activation | [‘relu’, ‘tanh’] | ||

| learning_rate | [0.000001, 0.00001, 0.0001] | ||

| kernel_regularizer = l2() | [0.000001, 0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1] | ||

| dropout | [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5] | ||

| Freezing layers | Custom implementation | ||

| Questions | Hypotheses | Outcome Measures | Sampling Plan (N, Power Analyses) | Analysis Plan | Interpretation Given to Different Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

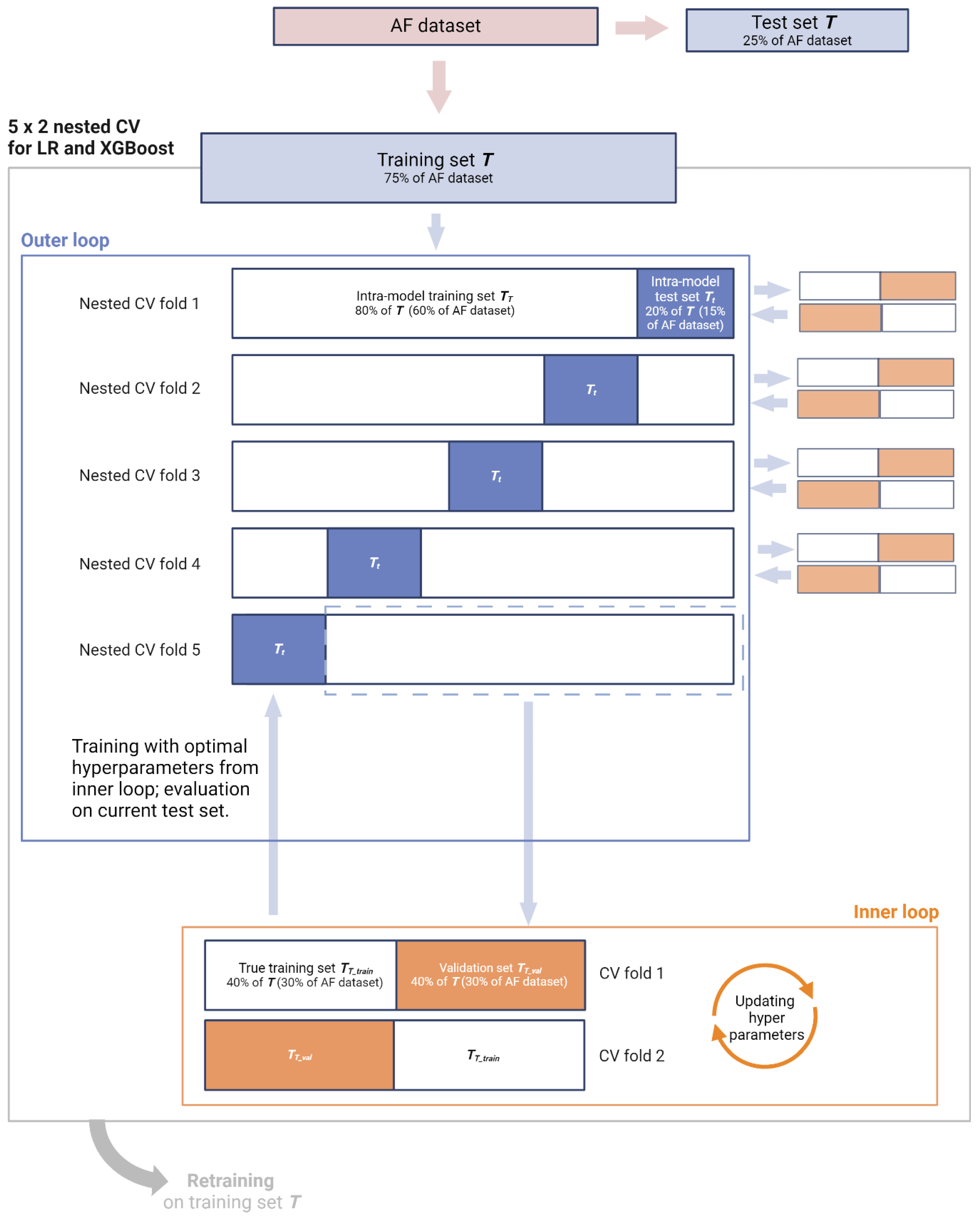

| Primary: Does the acute context of AFAIS, and the importance of the index event, call for a CPR bespoke to early secondary prevention? In other words, are the main effects of the constituent features of CHA2DS2-VASc different post-stroke? Besides main effects, are there synergistic or other non-linear interaction effects between stroke history and the constituent features of CHA2DS2-VASc that can further improve prediction of 90-day AFAIS recurrence? Secondary: How do CPRs trained to capture 90-day AFAIS recurrence perform with regard to secondary outcomes (7-day recurrence, 7- and 90-day HT, 90-day decline in functional status, and 90-day all-cause mortality)? Exploratory: How do CPRs trained to capture 90-day AFAIS recurrence perform with regard to recurrence among non-AF AIS patients? | Primary: LR and XGBoost can capture the main effects of the constituent features of CHA2DS2-VASc in the context of secondary prevention. XGBoost is also equipped to capture complex functional relationships between the features. The outputs of these models can be employed to construct CPRs that outperform CHA2DS2-VASc for predicting 90-day recurrence in AFAIS patients. Specifically, fair (AUC < 0.8) to good (< 0.9) discrimination can be achieved for this high-risk group, alongside improved calibration and clinical utility relative to CHA2DS2-VASc. Secondary: The resulting CPRs also outperform CHA2DS2-VASc for predicting secondary outcomes. | LR and XGBoost models: Discrimination assessed using AUC and calibration curves. Calibration assessed using calibration curves, slopes, and Brier scores. Additional metrics: F1 score, accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, Youden index, PPV, NPR, PLR, NLR. Resulting CPRs: Discrimination assessed using AUC and calibration curves. Calibration assessed using calibration curves, slopes, and Brier scores. Clinical utility assessed via DCA relative to default strategies as well as CHA2DS2-VASc. Test tradeoff analysis will be used to balance ease-of-use with clinical utility. | Primary: LR—680 patients deemed necessary, see Appendix S5.3 in Supplementary Materials file S3. XGBoost—learning curve analysis and KL divergence will afford post hoc insight on suitability of sample size. 75% of AF dataset will be used, comprising 2072 AFAIS patients. Remaining 25% (691 patients) will be withheld as test set. Secondary: Entire AF dataset will be used, comprising 2763 AFAIS patients. Exploratory: Entire non-AF dataset will be used as supplementary test set, comprising 7809 AIS patients. | Models will be instantiated (LR with L2 regularisation and XGBoost with default hyperparameters) on AF dataset, randomly split into training (T, 75%) and test sets (t, 25%), preserving distribution of outcomes. Nested cross-validation (5 × 2) will be employed for training and hyperparameter tuning. After hyperparameters are optimised, final models will be retrained using the entire training set. The test set t will then be used for evaluation of final LR and XGBoost models, focusing on discrimination and calibration. Feature importance will be reported via coefficients and odds ratios (ORs) for LR and feature gain for XGBoost. To derive CPRs from these models, SHAP will quantify both main effects and interaction effects of predictor variables. Main effects, represented by mean SHAP values, will be used to rank and assign scores to each predictor, enabling the creation of interpretable and clinically applicable CPRs. Interaction effects, captured through SHAP interaction values, will further refine our CPRs by identifying significant synergistic or redundant relationships between predictors. These interactions will be incorporated into so-called ‘augmented CPRs’ in the form of accompanying rules. Both non-augmented and augmented CPRs will be evaluated on the test set t in terms of discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility. Clinical utility will be measured using NB via DCA, plotting NB against risk thresholds within the 0.01–0.20 range. The CPRs will be compared on the basis of clinical utility to one another, CHA2DS2-VASc, and default strategies (‘treat all’ and ‘treat none’). Test tradeoff analysis will evaluate whether any incremental benefit in clinical utility observed with augmented CPRs justifies the added complexity of incorporating accompanying rules. Secondary: CPRs (and not models) will be evaluated on the entire AF dataset for each secondary outcome via discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility. Exploratory: CPRs (and not models) will be evaluated on the entire non-AF cohort to assess generalisability and compare their clinical utility when applied to an unseen yet closely related patient population. | Discrimination will be classified as follows [101]: AUC of 0.81–0.90 = good, 0.71–0.80 = fair, 0.61–0.70 = modest, and 0.51–0.60 = poor. Miscalibration is detrimental to medical decision making and poor calibration has been coined the Achilles heel for CPR applicability [102]. As such, we consider at least as important as discrimination and give precedence to clinical utility, which provides a more comprehensive evaluation by integrating both discrimination and calibration when interpreting the performance of our CPRs. CPRs will be considered clinically useful at a given risk threshold only if their NBs exceed those of both default strategies. Of those deemed useful, we will rank the CPRs (including CHA2DS2-VASc) based on NB across the 0.01–0.20 risk thresholds. Test tradeoff (∆NB) will be interpreted only insofar as spotlighting those CPRs which would be more conveniently deployable without sacrificing significant clinical utility. |

| Questions | Hypotheses | Outcome Measures | Sampling Plan (N, Power Analyses) | Analysis Plan | Interpretation Given to Different Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary: Does the acute context of AFAIS, and the importance of the index event, call for a CPR bespoke to early secondary prevention? In other words, are the main effects of the constituent features of CHA2DS2-VASc different post-stroke? Besides main effects, are there synergistic or other non-linear interaction effects between stroke history and the constituent features of CHA2DS2-VASc that can further improve prediction of 90-day AFAIS recurrence? Secondary: How do CPRs trained to capture 90-day AFAIS recurrence perform with regard to secondary outcomes (7-day recurrence, 7- and 90-day HT, 90-day decline in functional status, and 90-day all-cause mortality)? | Primary: MLP can capture the main effects of the constituent features of CHA2DS2-VASc in the context of secondary prevention, as well as complex functional relationships between stroke history and the other features. Its output can be employed to construct CPRs that outperform CHA2DS2-VASc for predicting 90-day recurrence in AFAIS patients. Specifically, fair (AUC <0.8) to good (<0.9) discrimination can be achieved for this high-risk group, alongside improved calibration and clinical utility relative to CHA2DS2-VASc. Secondary: The resulting CPRs also outperform CHA2DS2-VASc for predicting secondary outcomes. | See Table 3. | Learning curve analysis and KL divergence will afford post hoc insight on suitability of sample size. Data augmentation via transfer learning is particularly valuable for DL models like MLP, which are very data-hungry. Entire non-AF dataset will be used in pretraining phase, comprising 7809 AIS patients. 75% of AF dataset (T) will be used in fine-tuning phase, comprising 2072 AFAIS patients. Remaining 25% of AF dataset (t, 691 patients) will be withheld as test set. | The MLP model will leverage information within the non-AF patient dataset during pretraining. Non-AF AIS patients, who were not included in training the LR and XGBoost models—and therefore in no capacity informed the CPRs constructed thus far—may improve CPR generalisability and clinical utility. We contend our use case is well-suited to transfer learning given that the features of CHA2DS2-VASc are known to increase risk of AIS in patients without AF, and it has been reported to be equally predictive in the absence of AF [40]. MLP will be instantiated using default hyperparameters and undergo training, hyperparameter tuning, and retraining on the entire non-AF dataset to yield the pretrained model. The pretrained model will be evaluated (AUC, F1 score, precision, sensitivity, specificity) and its last layer(s) removed. These will be replaced by new, naive layers that culminate in an output layer with two neurons. The resulting neural network will be trained on the training set T. Two strategies will be tried: fine-tuning and freezing. In either case, the training phase will again employ nested CV (5 × 2) and the fine-tuned model will be retrained on the AF training set. Training performance will be reported using AUC, F1 score, accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and specificity, used to inform whether the purely fine-tuned or the frozen model will be retained for evaluation on the test set t. To derive CPRs from the MLP model’s output, SHAP will quantify main and interaction effects of predictor variables. Main effects, represented by mean SHAP values, will be used to rank and assign scores to each predictor. Interaction effects, captured through SHAP interaction values, will further refine our CPR by identifying significant synergistic or redundant relationships between predictors. These interactions will be incorporated into an ‘augmented CPR’ in the form of accompanying rules. Both non-augmented and augmented CPRs will be evaluated on the test set t in terms of discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility. The CPRs will be compared on the basis of clinical utility to one another, LR- and XGBoost-informed CPRs, CHA2DS2-VASc, and default strategies (‘treat all’ and ‘treat none’). Test tradeoff analysis will be performed. Secondary: CPRs (and not the MLP model) will be evaluated on the test set t for each secondary outcome via discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility. | See Table 3. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simon, J.; Kraiński, Ł.; Karliński, M.; Niewada, M.; on behalf of the VISTA-Acute Collaboration. Secondary Prevention of AFAIS: Deploying Traditional Regression, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning Models to Validate and Update CHA2DS2-VASc for 90-Day Recurrence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207327

Simon J, Kraiński Ł, Karliński M, Niewada M, on behalf of the VISTA-Acute Collaboration. Secondary Prevention of AFAIS: Deploying Traditional Regression, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning Models to Validate and Update CHA2DS2-VASc for 90-Day Recurrence. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207327

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimon, Jenny, Łukasz Kraiński, Michał Karliński, Maciej Niewada, and on behalf of the VISTA-Acute Collaboration. 2025. "Secondary Prevention of AFAIS: Deploying Traditional Regression, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning Models to Validate and Update CHA2DS2-VASc for 90-Day Recurrence" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207327

APA StyleSimon, J., Kraiński, Ł., Karliński, M., Niewada, M., & on behalf of the VISTA-Acute Collaboration. (2025). Secondary Prevention of AFAIS: Deploying Traditional Regression, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning Models to Validate and Update CHA2DS2-VASc for 90-Day Recurrence. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207327