Female Trans-Sphincteric Anterior Anal Fistula: Still an Unsolved Problem—Results from a Nationwide Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Patients and Variables

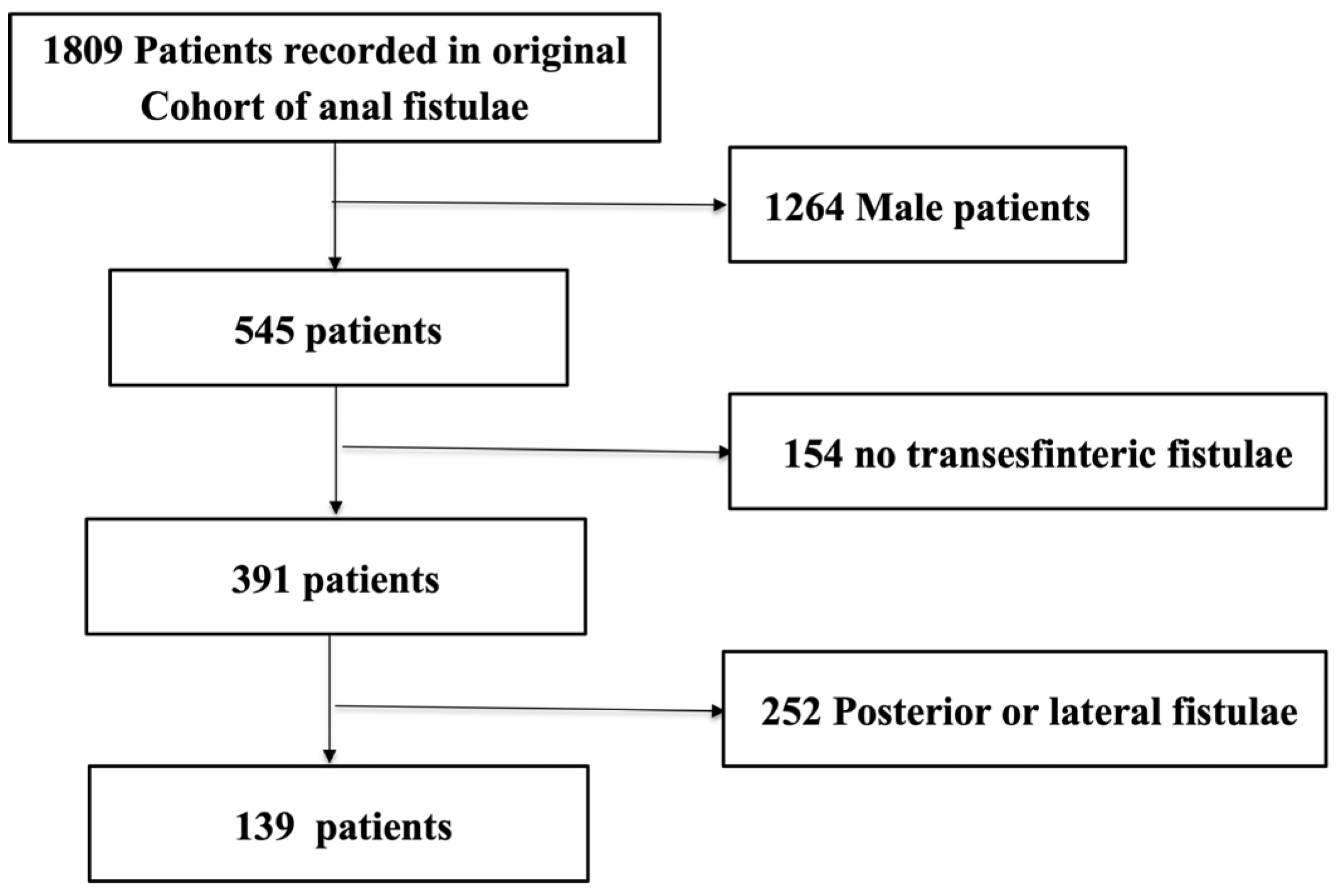

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- -

- AF healing: Total absence of perianal discharge, swelling or persistence of a perianal opening.

- -

- AF recurrence: Disappearance of discharge and/or swelling for at least 6 months followed by fistula reappearance.

- -

- AF persistence: The presence of non-interrupted discharge since surgery.

- -

- Preoperatory FI: The loss of control at passing gas or feces during at least 3 months, having started symptoms within 6 months before surgery.

- -

- De novo postoperative FI: The loss of voluntary control in passing gas or feces during at least 8 weeks in the postoperative period, without previous incontinence.

2.3. Main Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

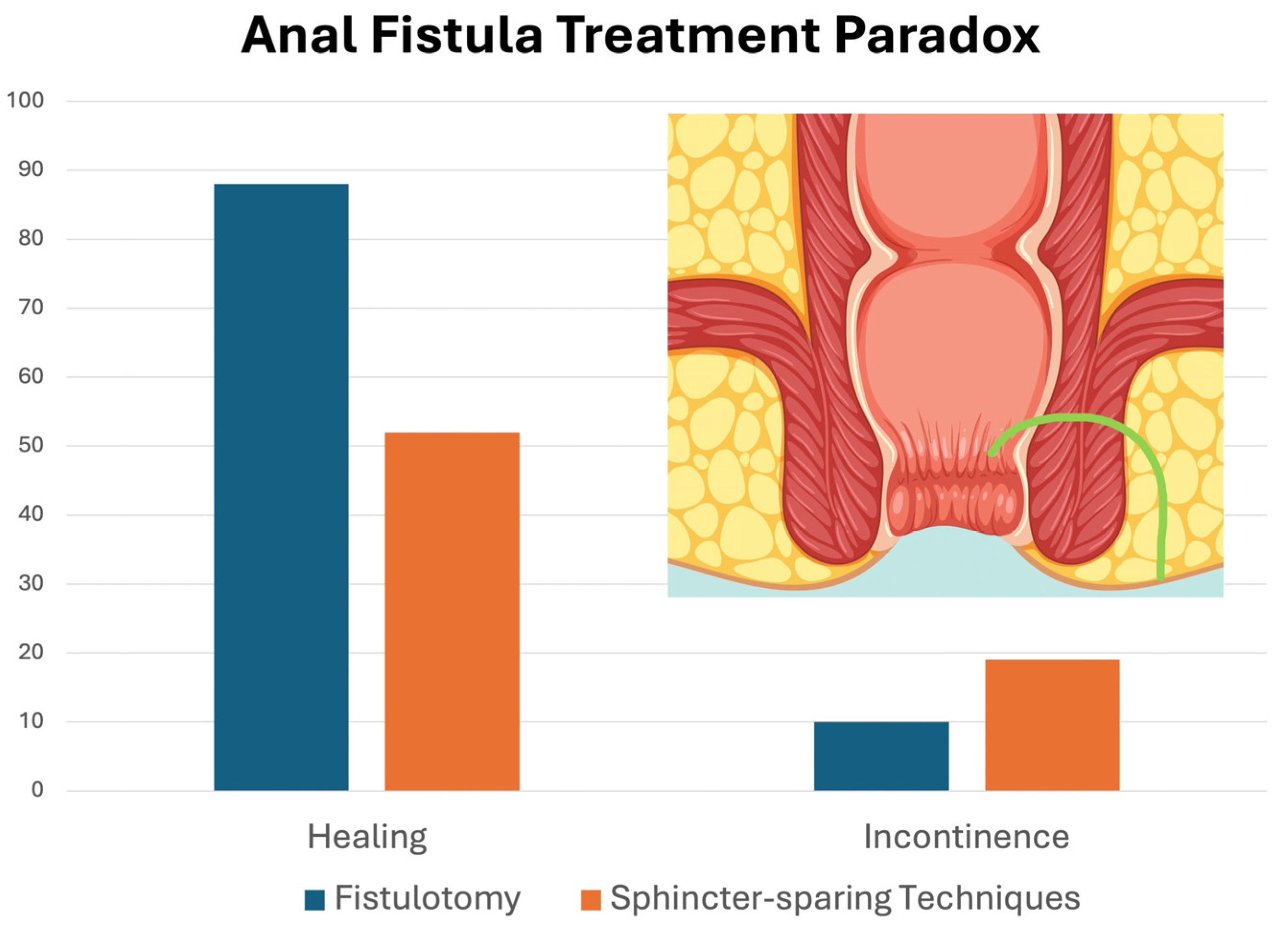

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | anal fistula |

| F-TAAF | female trans-sphincteric anterior anal fistula |

| FI | fecal incontinence |

| GJ-AECP | Group of Young Colorectal Surgeons of the Spanish Association of Coloproctology (Grupo Joven de la Asociación Española de Coloproctología) |

| CCIS | Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score |

| LIFT | inter-sphincteric ligation of the fistula tract |

| FiLaC | fistula laser closure |

| VAAFT | video-assisted ablation of fistula tract |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Cerdan Santacruz, C.; Santos Rancano, R.; Vigara Garcia, M.; Fernandez Perez, C.; Ortega Lopez, M.; Cerdan Miguel, J. Prevalence of anal incontinence in a working population within a healthcare environment. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, A.G.; Gordon, P.H.; Hardcastle, J.D. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br. J. Surg. 1976, 63, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Valderrama, Ó.; Miguel, T.F.; Bonito, A.C.; Muriel, J.S.; Fernández, F.J.M.; Ros, E.P.; Cabrera, A.M.G.; Cerdán-Santacruz, C. Surgical treatment trends and outcomes for anal fistula: Fistulotomy is still accurate and safe. Results from a nationwide observational study. Tech. Coloproctol. 2023, 27, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, J.M.; Wexner, S.D. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1993, 36, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.; Bharucha, A.E.; Chiarioni, G.; Felt-Bersma, R.; Knowles, C.; Malcolm, A.; Wald, A. Functional Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Reza, L.; Gottgens, K.; Kleijnen, J.; Breukink, S.; Ambe, P.C.; Aigner, F.; Aytac, E.; Bislenghi, G.; Nordholm-Carstensen, A.; Elfeki, H.; et al. European Society of Coloproctology: Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of cryptoglandular anal fistula. Color. Dis. 2024, 26, 145–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, J.; Mantilla, N.; Abcarian, A.; Kochar, K.; Marecik, S.; Chaudhry, V.; Mellgren, A.; Nordenstam, J. Sphincter-Sparing Anal Fistula Repair: Are We Getting Better? Dis. Colon Rectum 2017, 60, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göttgens, K.W.A.; Janssen, P.T.J.; Heemskerk, J.; van Dielen, F.M.H.; Konsten, J.L.M.; Lettinga, T.; Hoofwijk, A.G.M.; Belgers, H.J.; Stassen, L.P.S.; Breukink, S.O. Long-term outcome of low perianal fistulas treated by fistulotomy: A multicenter study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2015, 30, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.; Xu, W.; Varghese, C.; Dubey, N.; Wells, C.I.; Harmston, C.; O’gRady, G.; Bissett, I.P.; Lin, A.Y. Efficacy of different surgical treatments for management of anal fistula: A network meta-analysis. Tech. Coloproctol. 2023, 27, 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litta, F.; Parello, A.; Ferri, L.; Torrecilla, N.O.; Marra, A.A.; Orefice, R.; De Simone, V.; Campennì, P.; Goglia, M.; Ratto, C. Simple fistula-in-ano: Is it all simple? A systematic review. Tech. Coloproctol. 2021, 25, 385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Stellingwerf, M.E.; van Praag, E.M.; Tozer, P.J.; Bemelman, W.A.; Buskens, C.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endorectal advancement flap and ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for cryptoglandular and Crohn’s high perianal fistulas. BJS Open 2019, 3, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra Fernandez, I.; Balciscueta Coltell, Z.; Uribe Quintana, N. Systematic review and network meta-analysis of cryptoglandular complex anal fistula treatment: Evaluation of surgical strategies. Updates Surg. 2025, 77, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco Teres, L.; Cerdan Santacruz, C.; Garcia Septiem, J.; Maqueda Gonzalez, R.; Lopesino Gonzalez, J.M.; Correa Bonito, A.; Martín-Pérez, E. Patients’ Perceived Satisfaction Through Telephone-Assisted Tele-Consultation During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic Period: Observational Single-Centre Study at a Tertiary-Referral Colorectal Surgery Department. Surg. Innov. 2022, 29, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oostendorp, J.Y.; Verkade, C.; Han-Geurts, I.J.M.; van der Mijnsbrugge, G.J.H.; Wasowicz-Kemps, D.K.; Zimmerman, D.D.E. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) for trans-sphincteric cryptoglandular anal fistula: Long-term impact on faecal continence. BJS Open 2024, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Teres, L.; Bermejo Marcos, E.; Cerdan Santacruz, C.; Correa Bonito, A.; Rodriguez Sanchez, A.; Chaparro, M.; Gisbert, J.P.; Septiem, J.G.; Martin-Perez, E. FiLaC(R) procedure for highly selected anal fistula patients: Indications, safety and efficacy from an observational study at a tertiary referral center. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2023, 115, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marref, I.; Spindler, L.; Aubert, M.; Lemarchand, N.; Fathallah, N.; Pommaret, E.; Soudan, D.; Moult, H.P.-L.; Far, E.S.; Fellous, K.; et al. The optimal indication for FiLaC® is high trans-sphincteric fistula-in-ano: A prospective cohort of 69 consecutive patients. Tech. Coloproctol. 2019, 23, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emile, S.; Khafagy, W.; Elbaz, S. Impact of number of previous surgeries on the continence state and healing after repeat surgery for recurrent anal fistula. J. Visc. Surg. 2022, 159, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescatori, M. Surgery for anal fistulae: State of the art. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2071–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, D.D.E.; Delemarre, J.B.V.M.; Gosselink, M.P.; Hop, W.C.J.; Briel, J.W.; Schouten, W.R. Smoking affects the outcome of transanal mucosal advancement flap repair of trans-sphincteric fistulas. Br. J. Surg. 2003, 90, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Ge, M.; Du, P.; Yang, W.; He, Y. Risk Factors for Recurrence after anal fistula surgery: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2019, 69, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichanavichkij, P.; Vollebregt, P.F.; Keshishian, K.; Knowles, C.H.; Scott, S.M. The Clinical Impact of Obesity in Patients With Disorders of Defecation: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1155 Patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I.; Jones, O.M.; Smilgin-Humphreys, M.M.; Cunningham, C.; Mortensen, N.J. Patterns of Fecal Incontinence After Anal Surgery. Dis. Colon Rectum 2004, 47, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad-Regadas, S.M.M.; Regadas, F.S.P.M.; Mont’aLverne, R.E.D.; Fernandes, G.O.M.d.S.; de Souza, M.M.; Frota, N.d.A.; Ferreira, D.G. Impact of Internal Anal Sphincter Division on Continence Disturbance in Female Patients. Dis. Colon Rectum 2023, 66, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommer, A.; Wenger, F.A.; Rolfs, T.; Walz, M.K. Continence disorders after anal surgery—A relevant problem? Int. J. Color. Dis. 2008, 23, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litta, F.; Parello, A.; De Simone, V.; Grossi, U.; Orefice, R.; Ratto, C. Fistulotomy and primary sphincteroplasty for anal fistula: Long-term data on continence and patient satisfaction. Tech. Coloproctol. 2019, 23, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, D.D.E.; Gosselink, M.P.; Hop, W.C.J.; Darby, M.; Briel, J.W.; Schouten, R.W. Impact of two different types of anal retractor on fecal continence after fistula repair: A prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Dis. Colon Rectum 2003, 46, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunniss, P.J.; Kamm, M.A.; Phillips, R.K.S. Factors affecting continence after surgery for anal fistula. Br. J. Surg. 1994, 81, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n = 139 | ||

| Age (years) * | 45.8 (43.6–47.9) | |

| Duration of symptoms before surgery (months) * | 21.2 (17.7–24.6) | |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 46 (35.3%) | |

| Diabetes | 11 (7.9%) | |

| Current smoker | 33 (24.6%) | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 14 (10.1%) | |

| Previous anal surgery | 71 (51%) | |

| Previous AF surgery | 41 (29.5%) | |

| Patients with 2 or more anal fistula surgeries | 13 (9.3%) | |

| Previous perianal abscess | 86 (61.9%) | |

| Previous delivery (in women) | 58 (53.7%) | |

| Preparatory surgeries before the definitive procedure | None | 38 (27.34%) |

| 1 | 55 (39.57%) | |

| 2 | 31 (22.3%) | |

| 3 or more | 15 (10.79%) | |

| Preoperative fecal incontinence | 6 (4.3%) | |

| Cleveland Clinical Incontinence Score in patients with preoperative FI * | 3.8 (2.2–6.4) | |

| n = 139 | ||

| Trans-sphincteric fistula classification | Low | 50 (36%) |

| Medium | 67 (48%) | |

| High | 22 (16%) | |

| Multiple tracts | 11 (7.9%) | |

| Associated abscess | 14 (10%) | |

| Cryptoglandular origin | 120 (83.6%) | |

| Surgical procedure | Fistulotomy | 41 (29.5%) |

| LIFT | 31 (22.3%) | |

| Platelet-rich plasma | 14 (10%) | |

| Advancement flap | 13 (9.3%) | |

| Fistulotomy + sphincter repair | 12 (8.6%) | |

| Drain seton | 8 (5.7%) | |

| Fibrin sealant | 8 (5.8%) | |

| FiLaC | 5 (3.6%) | |

| Cutting seton | 5 (3.6%) | |

| Stem cells | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Anal plug | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Fistulotomy | Sphincter-Sparing Surgical Techniques | Sphincter-Sparing Minimally Invasive Procedures | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low fistula | Healing (n = 36, 78.3%) | 26 (89.7%) | 8 (61.5%) | 2 (50%) | 0.04 |

| Non-healing (n = 10, 21.7%) | 3 (10.3%) | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (50%) | ||

| Medium fistula | Healing n = 34, 54.0%) | 10 (83.3%) | 13 (43.3%) | 11 (52.4%) | 0.06 |

| Non-healing (n = 29, 46.0%) | 2 (16.7%) | 17 (56.7%) | 10 (47.6%) | ||

| High fistula | Healing (n = 10, 58.8%) | -- | 8 (61.5%) | 2 (50%) | 0.68 |

| Non-healing (n = 7, 41.2%) | -- | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (50%) | ||

| Healing (84, 60.4%) | Non-Healing (55, 39.6%) | OR (95%-CI) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) * | 46.2 (43.3–48.8) | 45 (41.3–48.7) | - | 0.5 | |

| Duration of symptoms (months) * | 19.3(14.8–23.8) | 24 (18.4–29.6) | - | 0.05 | |

| Obesity | 22 (28.2%) | 24 (46.1%) | 0.45 (0.22–0.95) | 0.04 | |

| Diabetes | 5 (5.95%) | 6 (11%) | 0.5 (0.1–1.6) | 0.2 | |

| Current smoker | 14 (17.3%) | 19 (35.8%) | 0.37 (0.17–0.83) | 0.01 | |

| Previous anal surgery | 38 (45.2%) | 33 (60%) | 0.5 (0.2–1.09) | 0.08 | |

| Previous anal fistula surgery | 22 (26.2%) | 19 (34.5%) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.2 | |

| Previous perianal abscess | 48(57.1%) | 38(69.1%) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.15 | |

| Previous delivery | 37 (52.1%) | 21 (56.8%) | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | 0.65 | |

| Preparatory surgeries before the definitive procedure | None | 27 (32.1%) | 11 (20%) | 3.28 (2.32–4.64) | 0.00 |

| 1 | 34 (40.4%) | 21 (38.2%) | 2.19 (1.56–3.08) | <0.01 | |

| 2 | 15 (17.9%) | 16 (29.9%) | 1.53 (1.03–2.27) | 0.02 | |

| 3 or more | 8 (9.5%) | 7 (12.7%) | -- | ||

| Preoperative fecal incontinence | 2 (2.3%) | 4 (7.2%) | 0.3 (0–1.5) | 0.1 | |

| Multiple tracts | 5 (6%) | 6 (10%) | 0.5 (0.1–1.6) | 0.2 | |

| Associated abscess | 5 (5.9%) | 9 (16.3%) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 0.046 | |

| Anal Fistula Origin | Cryptoglandular origin | 78 (92.9%) | 47 (85.4%) | 0.5 (0.1–1.6) | 0.2 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 6 (7.1%) | 8 (14.5%) | |||

| Surgical procedure | Fistulotomy | 36 (45%) | 5 (10.8%) | 8.6 (6.31–11.98) | 0.03 |

| Sphincter-sparing surgical techniques | 29 (36.2%) | 27 (58.7%) | 2.21 (1.55–3.14) | <0.01 | |

| Sphincter-sparing mini-invasive procedures | 15 (18.7%) | 14 (30.4%) | -- | ||

| Variables | OR | 95%-CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical procedure | Sphincter-sparing mini-invasive procedures | Reference | - | - |

| Fistulotomy | 5.9 | (1.7–21.6) | 0.006 | |

| Sphincter-sparing surgical techniques | 0.8 | (0.3–2.1) | 0.608 | |

| Current smoker | 3.1 | (1.2–8.3) | 0.021 | |

| Number of preparatoy surgeries | 0.7 | (0.5–0.96) | 0.03 | |

| Fistulotomy | Sphincter-Sparing Surgical Techniques | Sphincter-Sparing Mini-Invasive Procedures | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low fistula | FI (n = 7, 15.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 3 (25.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.430 |

| No FI (n = 38, 84.4%) | 26 (89.7%) | 9 (75.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| Medium fistula | FI (n = 6, 9.8%) | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (10.3%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0.991 |

| No FI (n = 55, 90.5%) | 10 (90.9%) | 26 (89.7%) | 19 (90.5%) | ||

| High fistula | FI (n = 4, 25.0%) | -- | 4 (33.3%) | 0 | 0.182 |

| No FI (n = 12, 75.0%) | -- | 8 (66.7%) | 4 (100%) | ||

| Variables | Postoperative FI | No Postoperative FI | OR (95%-CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) * | 47.6 (42.4–52.8) | 45.4 (43–47.8) | - | 0.6 |

| Obesity | 9 (64.2%) | 34 (30.6%) | 4.13 (1.34–12.65) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes | 2(11.7%) | 9 (7.6%) | 1.6 (0–7.39) | 0.55 |

| Current smoker | 4 (28.5%) | 27 (23.2%) | 1.3 (0.4–4.3) | 0.6 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 (5.8%) | 13 (11%) | 0.5 (0–3.2) | 0.51 |

| Previous anal surgery | 9 (53%) | 59 (50%) | 1.13 (0.42–3.03) | 1 |

| Previous anal fistula surgery | 8 (47%) | 30 (25.4%) | 3 (0.7–12) | 0.1 |

| Time of symptoms * | 20.9 (17.1–24.7) | 20.6 (10.5–30.7) | - | 0.06 |

| Previous perianal abscess | 4 (23.5%) | 79 (67.0%) | 0.2 (0.05–0.5) | <0.01 |

| Preparatory surgeries before definitive procedure | ||||

| None | 7 (41.2%) | 31 (26.2%) | - | - |

| 1 | 6 (35.2%) | 47 (39.8%) | 0.57 (0.17–1.84) | 0.612 |

| 2 | 3 (7.6%) | 27 (22.8%) | 0.49 (0.12–2.09) | |

| 3 or more | 1 (5.8%) | 13 (11%) | 0.34 (0.04–3.05) | |

| Anal fistula characteristics | ||||

| Multiple tracts | 2 (11.7%) | 8 (6.7%) | 1.8 (0–8.5) | 0.4 |

| Associated abscess | 0 | 13 (11%) | 0 (0–1.8) | 0.1 |

| Cryptoglandular origin | 15 (93.7%) | 101 (87.8%) | 0.48 (0.05–3.9) | 0.5 |

| Surgical procedure | ||||

| Fistulotomy | 4 (23.5%) | 36 (34.2%) | --- | 0.386 |

| Sphincter-sparing surgery | 10 (58.8%) | 43 (41%) | 2.09 (0.60–4.12) | |

| Sphincter-sparing mini-invasive procedures | 3 (17.6%) | 26 (24.7%) | 1.04 (0.21–3.68) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correa Bonito, A.; Cano Valderrama, Ó.; Muinelo Lorenzo, M.; Ochoa Villalabeitia, B.; Ocaña Jiménez, J.; Martín Pérez, B.; Cristóbal Poch, L.; Fernández Miguel, T.; Cerdán Santacruz, C.; on behalf of Young Group of Spanish Coloproctology Association. Female Trans-Sphincteric Anterior Anal Fistula: Still an Unsolved Problem—Results from a Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207326

Correa Bonito A, Cano Valderrama Ó, Muinelo Lorenzo M, Ochoa Villalabeitia B, Ocaña Jiménez J, Martín Pérez B, Cristóbal Poch L, Fernández Miguel T, Cerdán Santacruz C, on behalf of Young Group of Spanish Coloproctology Association. Female Trans-Sphincteric Anterior Anal Fistula: Still an Unsolved Problem—Results from a Nationwide Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207326

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorrea Bonito, Alba, Óscar Cano Valderrama, Manuel Muinelo Lorenzo, Begoña Ochoa Villalabeitia, Juan Ocaña Jiménez, Beatriz Martín Pérez, Lidia Cristóbal Poch, Tamara Fernández Miguel, Carlos Cerdán Santacruz, and on behalf of Young Group of Spanish Coloproctology Association. 2025. "Female Trans-Sphincteric Anterior Anal Fistula: Still an Unsolved Problem—Results from a Nationwide Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207326

APA StyleCorrea Bonito, A., Cano Valderrama, Ó., Muinelo Lorenzo, M., Ochoa Villalabeitia, B., Ocaña Jiménez, J., Martín Pérez, B., Cristóbal Poch, L., Fernández Miguel, T., Cerdán Santacruz, C., & on behalf of Young Group of Spanish Coloproctology Association. (2025). Female Trans-Sphincteric Anterior Anal Fistula: Still an Unsolved Problem—Results from a Nationwide Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207326