Abstract

Circulatory disturbances in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) present significant challenges in interventional cardiology. This review examines the pathophysiological mechanisms, management strategies, and outcomes associated with these hemodynamic complications, ranging from transient hypotension to severe cardiogenic shock (CS). The complex interplay between myocardial ischemia, reperfusion injury, and procedural stress creates a dynamic circulatory environment that requires careful monitoring and intervention. The review analyzes various causes of circulatory disturbances, including vasovagal reflexes, allergic reactions, cardiac arrhythmias, acute ischemia, and procedural complications. It emphasizes the importance of early recognition and appropriate management of these conditions to improve patient outcomes. The progression from hypotension to CS is examined, with a focus on assessment tools, prognostication, and revascularization strategies. The role of mechanical circulatory support devices in managing severe circulatory compromise is discussed, including intra-aortic balloon pumps, Impella devices, and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO). Recent randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results regarding the efficacy of these devices, highlighting the need for a nuanced, patient-centered approach to their use. This comprehensive analysis provides clinicians with a framework for anticipating, identifying, and managing circulatory disturbances in ACS patients undergoing PCI. It underscores the importance of risk stratification, multidisciplinary approaches, and ongoing research to optimize patient care and improve outcomes in this high-risk population.

1. Background

Circulatory disturbances in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) represent a significant challenge in interventional cardiology. These hemodynamic complications, ranging from transient hypotension to severe cardiogenic shock (CS), can profoundly impact patient outcomes and procedural success [1,2]. The complex interplay between myocardial ischemia, reperfusion injury, and the physiological stress of the intervention itself creates a dynamic and potentially precarious circulatory environment [3,4,5].

This review article aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the circulatory disturbances encountered in ACS patients during PCI, with a particular focus on hypotension, pre-shock states, and CS. We will examine the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these complications, including blood pressure fluctuations, alterations in tissue perfusion, and signs of end-organ hypoperfusion. By characterizing the progression of circulatory instability in these patients, we seek to enhance understanding of the various stages of hemodynamic compromise and their clinical implications.

The timing of circulatory disturbances in relation to PCI is of particular interest, as these complications can manifest before, during, or after the procedure [4]. Each temporal phase presents unique challenges in terms of etiology, diagnosis, and management [5,6]. The multifactorial nature of these disturbances, which can include vagal responses, myocardial stunning, and procedure-related complications such as coronary perforation or no-reflow phenomenon, necessitates a nuanced approach to patient care [4].

By synthesizing current evidence and expert opinion, this review aims to provide clinicians with a comprehensive framework for anticipating, identifying, and managing circulatory disturbances in ACS patients undergoing PCI. Through this analysis, we hope to contribute to improved patient outcomes and advance the field of interventional cardiology in managing this high-risk patient population.

This review was conducted using a structured literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Google Scholar. Search terms included “acute coronary syndrome,” “hypotension,” “cardiogenic shock,” “mechanical circulatory support,” “Impella,” “IABP,” “ECMO,” “no-reflow,” and related keywords. Priority was given to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), large registries, and meta-analyses, while narrative reviews and expert consensus documents were included to provide contextual interpretation.

Studies were included if they involved adult patients undergoing PCI for ACS with reported hemodynamic complications or MCS use. Exclusion criteria were case reports, pediatric studies, and non-English publications.

2. Hypotension

Hypotension during and after PCI represents a multifaceted clinical challenge that demands careful consideration and prompt intervention. This hemodynamic instability, characterized by a significant decrease in blood pressure, can arise from various physiological and procedural factors associated with the intervention [7]. The complexity of this condition lies in its potential to rapidly deteriorate into CS, a life-threatening complication with high morbidity and mortality rates [6,7]. Recognizing the early signs of hypotension and implementing appropriate therapeutic strategies are crucial steps in preventing adverse outcomes and optimizing patient care in the context of PCI procedures. The following discussion aims to explore the etiology, risk factors, and management strategies for hypotension in the peri-PCI period, emphasizing the importance of vigilant monitoring and timely intervention to improve patient outcomes.

2.1. Vasovagal Reflexes

The activation of vagal reflexes can transiently reduce cardiac output. A notable instance is the Bezold–Jarisch reflex (BJR), commonly observed in inferior myocardial infarction (MI) during reperfusion. BJR is characterized by a triad of bradycardia, hypotension, and peripheral vasodilation, which is triggered by the stimulation of cardiac vagal afferents, predominantly located in the inferoposterior wall, during ischemia or sudden reperfusion [8]. The reflex induces an abrupt parasympathetic surge and sympathetic withdrawal; even when heart rate is maintained through pacing, significant vasodilation occurs, thereby reducing both preload and afterload. Clinically, this phenomenon can manifest during a right coronary artery (RCA) or left circumflex artery (LCx) PCI for inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), resulting in sudden hypotension and often bradycardia immediately following the reopening of the artery [8,9]. Management is supportive, involving intravenous fluids, atropine, and vasoconstrictors such as epinephrine or phenylephrine, until the reflex subsides. Additionally, a more routine vasovagal reaction, unrelated to reperfusion, may occur due to pain or anxiety, similarly causing transient hypotension and bradycardia through increased vagal tone [10].

2.2. Allergic/Anaphylactoid Reaction

A sudden response to contrast media or other substances (such as protamine) can result in widespread vasodilation, capillary leakage, and shock. Although uncommon, anaphylaxis in the catheterization lab manifests as severe low blood pressure, often accompanied by rapid heartbeat, skin rash, or bronchospasm [11]. This reaction can occur within minutes following the injection of contrast. Immediate intervention is necessary, involving the use of epinephrine, steroids, and fluids. In one instance, contrast-induced anaphylaxis was considered among the possible causes of abrupt hypotension during PCI (Importantly, the patient’s low blood pressure did not respond to steroids or antihistamines, suggesting that an allergy was unlikely [12].

2.3. Cardiac Arrhythmias

Both bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias can precipitate hypotension during PCI. For instance, transient high-grade AV block or sinus pauses (especially during RCA/inferior wall ischemia) will drop cardiac output and blood pressure [13]. On the other end, a ventricular tachycardia (VT) or rapid atrial arrhythmia can compromise filling time and output. These arrhythmias may be procedure-related (e.g., ischemia-induced or triggered by guidewire irritation) and need prompt management if they cause hemodynamic instability [14].

2.4. Acute Ischemia, No-Reflow and Myocardial Stunning

Hypotension may indicate insufficient myocardial perfusion during intervention. The no-reflow phenomenon is characterized by impaired microvascular perfusion despite the patency of the epicardial artery. This condition is most frequently observed during PCI for acute myocardial infarction (MI) or in saphenous vein graft interventions. Mechanistically, no-reflow results from microvascular obstruction due to distal microthromboembolism, endothelial swelling, inflammatory damage, and edema, leading to persistent ischemia [15]. Clinically, no-reflow often manifests as sudden hypotension, bradycardia, and ST-segment changes, accompanied by recurrent chest pain, even after successful stent placement. One registry reported no-reflow in approximately 2.3% of MI PCI cases, while smaller studies suggest a higher incidence, ranging from 10% to 40% in high-risk MI cases. Notably, no-reflow is a significant cause of severe intraprocedural hypotension; one study identified it as the cause in 83% of cases of profound hypotension during PCI that required intracoronary epinephrine administration [16,17]. The treatment of no-reflow involves the use of intracoronary vasodilators, such as adenosine, verapamil, and nitroprusside, along with supportive care to enhance coronary microcirculation. Persistent no-reflow indicates a large area of myocardial stunning, often signaling the onset of CS. Additionally, myocardial stunning is a transient, reversible depression of left-ventricular contractility that persists after the relief of acute ischemia, despite viable myocardium and restored epicardial patency; classically, wall-motion abnormalities may take hours to days to normalize after reperfusion [18]. This phenomenon is characterized by a prolonged period of reduced contractility even after blood flow has been restored. During PCI, the temporary occlusion of a coronary artery can lead to this stunning effect. The stunned myocardium, while still viable, exhibits impaired function, which can contribute to a temporary decrease in cardiac output. This reduction in cardiac performance may result in hypotension following the procedure. The exact mechanisms of stunning are complex, but they likely involve calcium overload within the cardiomyocytes and increased production of reactive oxygen species during reperfusion. These factors can interfere with the normal contractile function of the heart muscle cells. The hypotension that follows is a consequence of this reduced contractility and the subsequent decrease in cardiac output. It is important to note that while stunning is generally reversible, it can take hours or even days for the myocardium to fully recover its function after the ischemic event [19,20].

A related but distinct ischemic complication is right ventricular infarction (RVI), which most frequently occurs in the context of inferior STEMI. RVI results in disproportionate hypotension despite a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, highlighting the right ventricle’s sensitivity to ischemia and its reliance on adequate preload. In contrast to left ventricular dysfunction, hypotension in RVI is aggravated by the administration of nitrates or excessive diuresis, whereas cautious fluid resuscitation to enhance venous return is generally advantageous. The definitive treatment remains the urgent reperfusion of the culprit vessel, and temporary pacing may be necessary in the presence of bradyarrhythmia. Recognizing this unique hemodynamic profile is essential, as tailored management can swiftly reverse shock physiology and prevent progression to CS [7,21].

2.5. Procedural Complications

Procedural mechanical complications during PC can lead to sudden circulatory collapse by acutely impairing cardiac filling or forward flow. A quintessential example is cardiac tamponade resulting from coronary or chamber perforation, where rapid accumulation of pericardial blood elevates intrapericardial pressure, restricts diastolic filling, and causes a sharp decline in stroke volume and arterial pressure [22]. Any unexplained intra-procedural hypotension should prompt immediate evaluation for tamponade—preferably with point-of-care echocardiography—as timely pericardiocentesis is often lifesaving. Notably, delayed tamponade may occur when a small perforation or wire-related injury results in a slower pericardial effusion that becomes clinically evident during recovery; new hypotension in the hours following PCI warrants urgent reassessment even if the procedure appeared uncomplicated [23]. Clinical findings such as elevated jugular venous pressure, muffled heart sounds, and pulsus paradoxus support the diagnosis. Beyond overt perforation, intramural hematoma or a loculated pericardial clot can create “dry” or pseudo-tamponade with chamber compression and similar hemodynamic consequences without a large free effusion [24,25].

An additional critical mechanism is the damping or ventricularization of the pressure waveform, which transpires when the guiding catheter is inserted excessively into the coronary ostium. This can precipitate significant hemodynamic disturbances, resulting in hypotension and ischemia, particularly in the presence of ostial disease. This issue is notably more severe in left system interventions, potentially causing extensive ischemia and rapid clinical deterioration. Key indicators of this complication include a sudden alteration in the arterial pressure waveform, the absence of the dicrotic notch, and ventricularization of the tracing. Prompt repositioning of the catheter is essential for management, while prevention necessitates appropriate catheter selection, meticulous engagement techniques, and continuous monitoring of pressure waveforms. This complication underscores the necessity of precise technique and vigilant hemodynamic monitoring during PCI, especially in patients with unstable hemodynamics or complex anatomy [26].

In addition to mechanical injury, it is imperative to consider bleeding complications, particularly in the period following PCI. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is a well-documented cause of post-procedural hypotension, whereas gastrointestinal bleeding, associated with the concurrent use of dual antiplatelet therapy and parenteral anticoagulation, may initially be occult. In such instances, hypotension may precede overt clinical manifestations such as melena or hematemesis, highlighting the necessity for vigilance in patients who exhibit unexplained hemodynamic instability after PCI [7].

Other catastrophic but rare iatrogenic events—including catheter-induced aortic root dissection—may similarly trigger acute hemodynamic collapse and require expedited definitive management (e.g., surgical repair). Prompt recognition of these entities and execution of a structured response pathway—hemodynamic stabilization, immediate imaging, and targeted intervention—are critical to restoring perfusion and preventing progression to CS [27].

3. Cardiogenic Shock

CS represents the extreme end of circulatory disturbance in patients with ACS. It is a critical complication characterized by severe impairment of cardiac function, leading to inadequate tissue perfusion and organ dysfunction. Despite advances in treatment strategies, CS continues to be associated with unacceptably high mortality rates of 40–50% in ACS patients [28,29].

CS is defined by critical end-organ hypoperfusion and hypoxia resulting from reduced cardiac output due to primary cardiac disorders. Clinically, it manifests as persistent hypoperfusion unresponsive to volume replacement, evidenced by cold extremities, oliguria, altered mental status, and elevated arterial lactate levels [30]. The most common cause, accounting for approximately 80% of cases, is left or right ventricular failure following acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Less frequent causes include mechanical complications of AMI such as ventricular septal rupture, free wall rupture, and acute severe mitral regurgitation [30,31].

3.1. Assessment and Prognostication

Early identification of patients at risk of developing CS is crucial for improving outcomes. Various biomarkers and risk scores have been developed to aid in this process. Arterial lactate, particularly the 8 h value, has been shown to be a strong predictor of mortality [30,31]. The IABP-SHOCK II score, which incorporates biomarkers such as lactate, creatinine, and glucose, has been validated for risk stratification in AMI-CS patients. Early recognition allows for timely intervention and appropriate management strategies, potentially reducing the progression to full CS and improving patient outcomes [32,33].

Invasive assessment serves as a vital tool. While not essential for initial diagnosis in everyday clinical scenarios, the measurement of specific hemodynamic parameters through invasive monitoring provides critical data for confirming the diagnosis and directing treatment strategies. This typically involves evaluating the cardiac index, which is often decreased, and the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, which is usually elevated in CS [4,30].

The Swan-Ganz catheter, a type of pulmonary artery catheter, is frequently employed for this purpose. It enables the measurement of crucial variables including cardiac output, pulmonary artery pressure, and mixed venous oxygen saturation. A relatively new metric, the pulmonary artery pulsatility index (PAPI), has shown particular promise in evaluating right ventricular function in CS patients [33].

These invasive assessments are particularly valuable in cases where patients show unexpected responses to initial treatments. They offer detailed insights into the condition of both the right heart and the systemic circulation. Such information is invaluable for customizing treatment approaches and closely monitoring how patients respond to various interventions. Ultimately, this comprehensive invasive assessment can significantly contribute to improving outcomes in this critically ill patient population [3,30].

To standardize the assessment and management of CS, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) has developed a classification system comprising five stages: A (At risk), B (Beginning), C (Classic), D (Deteriorating), and E (Extremis), (Table 1). This classification aims to provide a framework for assessing the severity of CS and guiding treatment decisions. Stage A includes patients at risk but not yet experiencing shock, while Stage E represents extreme shock with circulatory collapse requiring ongoing CPR or multiple pressors or mechanical circulatory support devices [4].

Table 1.

SCAI Classification of Cardiogenic Shock [4,34].

The SCAI classification has been validated in several retrospective cohorts and one prospective study, demonstrating good correlation with prognosis. However, it is important to note that while this classification system is useful for evaluating the course of CS over time, it is currently not well-suited as an immediate numerical score for decision-making in the catheterization laboratory.

3.2. Coronary Revascularization

Timely management of ongoing ischemia is crucial in the treatment of CS complicating acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Coronary revascularization stands at the forefront of this management strategy, with a substantial body of evidence supporting its efficacy [30].

The landmark SHOCK trial [35], published in 1999, laid the foundation for early revascularization in CS. While it did not show a significant difference in 30-day mortality (46.7% vs. 56.0%, p = 0.11), it demonstrated a marked improvement in one-year survival (46.7% vs. 33.6%, p = 0.025) for early revascularization compared to initial medical stabilization. Long-term follow-up at 6 years further confirmed this benefit (32.8% vs. 19.6%, p = 0.03) [36].

Subsequent registry studies have reinforced the importance of timely intervention. The FITT-STEMI trial [37], involving 12,675 patients, showed that every 10 min delay in treatment was associated with 3.31 additional deaths per 100 PCI-treated CS patients, highlighting the critical nature of rapid revascularization.

The CULPRIT-SHOCK trial [38,39], published in 2017, provided crucial insights into the optimal revascularization strategy for CS patients with multivessel disease. This randomized study of 706 patients demonstrated that culprit-lesion-only PCI resulted in lower 30-day mortality compared to immediate multivessel PCI (43.3% vs. 51.6%, p = 0.03). The one-year follow-up confirmed this benefit, with mortality rates of 50.0% vs. 56.9% (p = 0.048) favoring the culprit-lesion-only approach.

Even in older populations (≥75 years) with CS, early revascularization appears to offer significant benefits according to an observational study of 111,901 patients in the United States from 1999 to 2013 [40]. The study found that the utilization of PCI in older adults with STEMI and CS increased from 27% in 1999 to 56% in 2013, accompanied by a substantial reduction in in-hospital mortality rates from 64% to 46% over the same period. Using propensity score matching methods to account for potential confounders, PCI was associated with a lower risk of in-hospital mortality across all quintiles of propensity score (Mantel-Haenszel OR: 0.48, 95% CI 0.45–0.51). This reduction in mortality risk was consistent across all four United States Census Bureau regions. The study’s findings suggest that, despite the higher risks associated with advanced age and CS, early revascularization with PCI can significantly improve survival outcomes in this vulnerable population.

The current body of evidence strongly supports early revascularization in CS, with a preference for culprit-lesion-only PCI in multivessel disease, followed by staged revascularization after clinical stabilization, (Table 2). This approach often leaves a high residual SYNTAX score, and the potential advantage of immediate surgical revascularization remains unclear [41]. Smilowitz et al. [42] conducted a large retrospective study that compared CABG versus PCI in patients with MI complicated by CS. Among 386,811 hospitalizations for MI with CS, 62.4% underwent revascularization, with PCI in 44.9% and CABG in 14.1% of cases. CABG was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality compared to PCI. In the overall population, CABG (without PCI) had a mortality rate of 18.9% versus 29.0% for PCI alone (p < 0.001). This mortality benefit persisted in a propensity-matched analysis of 19,882 patients, where CABG was associated with 19.0% mortality compared to 27.0% for PCI (p < 0.001). The study also observed an increase in coronary revascularization rates for MI and CS over time, from 51.5% in 2002 to 67.4% in 2014 (p-for-trend < 0.001). These findings suggest a potential benefit of CABG over PCI in patients with MI and CS, warranting further investigation through randomized trials.

Table 2.

Summary of Landmark Clinical Trials in Cardiogenic Shock: Revascularization Strategies and Mechanical Circulatory Support.

To address this uncertainty, investigators at NYU Langone have proposed the CABG-SHOCK trial [42], a randomized study that would compare culprit-only PCI with staged revascularization against immediate CABG in patients with acute myocardial infarction and CS. The trial’s goal is to determine whether complete surgical revascularization can reduce residual coronary disease and improve survival compared with a PCI-based strategy. However, the study has not yet progressed beyond the planning phase.

4. Pre-Shock State: Recognition and Management

Hypotension and CS should be understood as existing along a continuum rather than as distinct conditions. Patients may present in a “pre-shock” state, wherein compensatory mechanisms are beginning to fail, yet overt shock has not yet manifested. This phase is characterized by borderline hypotension (systolic blood pressure typically ranging from 80 to 100 mmHg), elevated lactate levels, and early indicators of tissue hypoperfusion, such as oliguria, tachycardia, cool extremities, and subtle alterations in mental status. Importantly, these symptoms occur in the absence of the sustained severe hypotension and multiorgan dysfunction that are characteristic of classic CS [4].

The fundamental pathophysiology is characterized by an imbalance between cardiac output and systemic demand. Acute ischemic injury, elevated filling pressures, and impaired ventricular–arterial coupling diminish effective forward flow. Even slight reductions in arterial pressure can significantly compromise coronary perfusion in the context of severe coronary disease, triggering a downward spiral of worsening ischemia and ventricular dysfunction [4,34].

Recognizing the onset of pre-shock necessitates vigilance, as the condition may deteriorate rapidly. Laboratory indicators, such as a lactate level exceeding 2 mmol/L or an increasing lactate trajectory, serve as early evidence of inadequate perfusion. Invasive hemodynamic assessments may reveal a cardiac index ranging from 1.8 to 2.2 L/min/m2, accompanied by elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, indicating limited cardiac reserve. Clinical warning signs at the bedside include narrowing pulse pressure, increasing vasopressor requirements, and a poor response to fluid challenges. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) classification identifies this phase as Stage B (“Beginning shock”), underscoring its prognostic significance and the necessity for early intervention [4].

Management strategies focus on preventing progression toward established shock. Rapid revascularization of the culprit lesion in the context of ACS is fundamental to therapy, as ongoing ischemia exacerbates hemodynamic instability. Hemodynamic support necessitates precise titration: cautious fluid resuscitation may benefit preload-dependent patients, whereas excessive resuscitation poses a risk of pulmonary edema. Inotropes and vasopressors may offer temporary stabilization; however, escalating requirements often indicate impending deterioration. Structured monitoring—encompassing continuous arterial pressure, serial lactate measurements, and urine output surveillance—is crucial for guiding therapy and detecting deterioration [44].

5. Mechanical Circulatory Support in Cardiogenic Shock

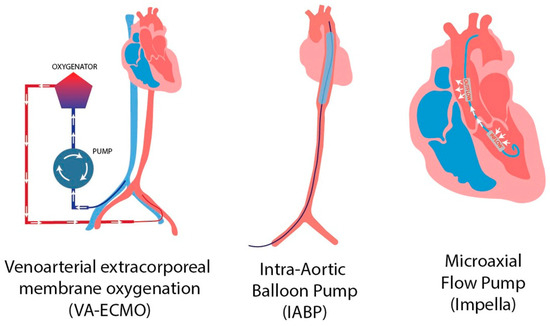

5.1. Rationale and Pathophysiologic Targets

Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices play a crucial role in managing CS. While pharmacologic interventions such as vasopressors and inotropes can improve perfusion pressure, they also increase myocardial oxygen demand [30]. In contrast, MCS devices aim to restore systemic blood flow and, depending on the specific platform, reduce ventricular load and wall stress, (Figure 1). This approach creates favorable physiological conditions for myocardial recovery while allowing for definitive therapeutic interventions, such as culprit-lesion revascularization or correction of mechanical complications [31,54].

Figure 1.

Mechanical circulatory support devices [55]. Reproduced from Putowski Z. et al. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2023;37(10):2065-72. CC BY 4.0.

The selection of an appropriate MCS device is based on several factors, including the patient’s hemodynamic phenotype (left-sided versus biventricular failure, presence of severe hypoxemia), disease trajectory (as assessed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions [SCAI] staging system), and the institution’s expertise, (Table 3). Contemporary management strategies incorporate SCAI staging and multidisciplinary “shock team” approaches, providing a standardized framework for the escalation and de-escalation of mechanical support [4,30,54].

Table 3.

Comparative Features of MCS Devices.

5.2. Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump (IABP)

The use of an IABP increases diastolic coronary pressure and slightly decreases afterload, but it offers limited forward flow support, providing less than 1 L/min. The significant IABP-SHOCK II randomized trial [33], which involved 600 patients with AMI-CS scheduled for early revascularization, found no reduction in 30-day mortality when comparing routine IABP use to no IABP (39.7% vs. 41.3%; RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.79–1.17). There were also no benefits in secondary outcomes or ICU course metrics, with similar rates of bleeding, sepsis, stroke, and limb ischemia in both groups. The results at twelve months remained unchanged. Consequently, routine IABP use in AMI-CS does not enhance survival and is not advised when early revascularization is possible. This evidence supports the downgrade of IABP for STEMI-CS in the 2025 ACC/AHA ACS guideline [1].

5.3. Impella

The Impella series consists of percutaneous, transvalvular micro-axial devices designed to assist the left ventricle by drawing blood from it and pumping it into the ascending aorta [57]. This process enhances systemic circulation and reduces the load on the left ventricle, which decreases LVEDP and wall stress, potentially improving coronary perfusion pressure and minimizing ischemic damage in cases of CS [58]. The Impella CP, the most frequently utilized model in AMI-CS, is typically inserted retrogradely through a 14 Fr femoral arterial sheath, crossing the aortic valve under fluoroscopic or echocardiographic guidance [58,59]. When properly positioned and maintained with continuous anticoagulation, it can provide approximately 3.5–4.0 L/min of forward flow. Other models, such as the smaller Impella 2.5 and the surgical/axillary platforms (5.0/5.5), offer varying flow rates, with the latter providing higher outputs. Risks associated with these devices include significant bleeding, vascular injury or limb ischemia, and hemolysis, which require careful management of access, anticoagulation, and monitoring protocols [44,60].

The initial hemodynamic randomized controlled trial, ISAR-SHOCK [61], involving 26 patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by AMI-CS, compared the Impella 2.5 device to intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), (Table 2). The study revealed significant acute improvements in cardiac index with Impella, but no difference in 30-day mortality. However, the trial’s small sample size limited its statistical power for clinical outcomes.

Subsequently, the IMPRESS trial [46], which included 48 patients with severe AMI-CS, mostly post-cardiac arrest, compared Impella CP to IABP. The results showed comparable mortality rates at 30 days and 6 months, with no significant difference at 5-year follow-up. However, Impella use was associated with higher rates of bleeding and hemolysis in the short term.

The recent DanGer Shock trial [50], published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2024, represents the first adequately powered randomized controlled trial evaluating Impella in AMI-CS patients undergoing emergency revascularization. This study randomized 355 participants to Impella CP plus standard care versus standard care alone. At 180 days, all-cause mortality was significantly reduced in the Impella group (45.8% vs. 58.5%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.55–0.99; p = 0.04). However, this survival benefit was accompanied by higher complication rates, including severe bleeding (24.0% vs. 12.8%), vascular complications (19.2% vs. 5.1%), and a greater need for renal replacement therapy (40.6% vs. 26.4%).

These findings necessitate a careful evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio and emphasize the importance of implementing precise implantation and management protocols. The 2025 ACC/AHA ACS guideline [1] reflects these results by providing a Class IIa recommendation for microaxial flow pumps (Impella CP) in select patients with severe or refractory STEMI-CS, while emphasizing the need for caution in their application.

Impella is being assessed in situations of non-CS, as demonstrated in the UK multicenter CHIP-BCIS3 trial [62]. This study involves randomizing patients who have extensive multivessel coronary disease and severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and who are undergoing non-emergent, complex PCI, to either elective percutaneous LV unloading or standard care. The primary endpoint, structured hierarchically as a win-ratio, encompasses all-cause mortality, stroke, spontaneous myocardial infarction (MI), cardiovascular hospitalization, and periprocedural MI, along with integrated cost-effectiveness and quality of life (QoL) analyses. Concurrently, the PROTECT IV [63] randomized controlled trial (RCT) is recruiting high-risk PCI patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) to compare Impella-supported PCI against unsupported PCI, with a focus on a composite outcome of death, stroke, MI, or cardiovascular hospitalization over an extended follow-up period. Collectively, these trials aim to determine if prophylactic microaxial support can facilitate more comprehensive revascularization and safer multivessel intervention in cases of advanced LV dysfunction—an area where previous randomized studies, such as PROTECT II [64], indicated hemodynamic benefits without a clear early clinical advantage, and where current guidelines emphasize ongoing uncertainty outside of shock scenarios.

5.4. Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (VA-ECMO)

VA-ECMO is an advanced mechanical circulatory support system used in severe cardiogenic shock. It temporarily assumes the role of the heart and lungs, providing circulatory and respiratory support through a system of cannulas, an extracorporeal circuit, a pump, an oxygenator, and a heat exchanger. The system drains deoxygenated blood from the venous system, oxygenates it, and returns it to the arterial system, improving systemic perfusion and oxygen delivery to end organs [52]. Recent randomized controlled trials have examined the efficacy of VA-ECMO in CS. The ECMO-CS trial [52] (n = 117) randomized patients with severe CS to immediate VA-ECMO versus an initially conservative strategy with rescue ECMO as needed, showing no difference in the composite endpoint of death, resuscitated circulatory arrest, or crossover to urgent ECMO at 30 days (63% vs. 71%; p = 0.78). The ECLS-SHOCK trial [51], the largest ECMO RCT to date (n = 420 AMI-CS patients), demonstrated 30-day all-cause mortality rates of 47.8% with early ECLS versus 49.0% with standard care (relative risk [RR] 0.98; 95% CI 0.80–1.19; p = 0.81). The primary endpoint of 30-day all-cause mortality was not significantly reduced. Importantly, the trial design permitted rescue ECMO in patients who deteriorated, which limits over-interpretation of the conclusion that routine early ECMO is not superior to standard care. The smaller EURO SHOCK pilot trial [56] (n = 35) observed a 30-day mortality of 43% in the ECMO arm versus 77% in controls, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.18) given its limited power. Collectively, these randomized studies indicate that routine early VA-ECMO does not improve short-term survival in AMI-CS and may increase complications. However, selective ECMO use—for example, in patients with profound hypoxemia or refractory biventricular failure—remains a potential consideration.

6. Conclusions

Circulatory disturbances in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention remain a significant challenge in interventional cardiology. This review has highlighted the complex interplay of factors contributing to hemodynamic instability, ranging from vasovagal reflexes and allergic reactions to severe complications like CS. The importance of early recognition and appropriate management of these disturbances cannot be overstated, as they can significantly impact patient outcomes.

The evolution of mechanical circulatory support devices has provided new options for managing severe circulatory compromise, particularly in cases of CS. However, recent randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results regarding their efficacy. While the DanGer Shock trial demonstrated a mortality benefit with routine Impella CP use in AMI-CS patients, this came at the cost of increased complications. Similarly, studies on VA-ECMO have not shown clear mortality benefits in CS, despite its theoretical advantages.

These findings underscore the need for a nuanced, patient-centered approach to managing circulatory disturbances in ACS patients undergoing PCI. The use of risk stratification tools, such as the SCAI classification system, and the implementation of multidisciplinary “shock team” approaches may help optimize patient care. Future research should focus on refining patient selection criteria for mechanical support devices and developing strategies to mitigate their associated complications.

Ultimately, improving outcomes in this high-risk patient population will require a combination of early recognition, rapid intervention, judicious use of advanced supportive technologies, and ongoing refinement of management protocols based on emerging evidence. As our understanding of the pathophysiology of circulatory disturbances in ACS continues to evolve, so too must our approaches to their prevention and management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.; methodology, T.A., M.E., M.F., and M.A.; investigation, T.A., M.F., and M.A.; resources, T.A., A.G., M.F., and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, T.A.; visualization, A.G., M.F., and M.A.; supervision, T.A. and M.E.; project administration, T.A. and M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation 2025, 85, 2135–2237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thiele, H.; de Waha-Thiele, S.; Freund, A.; Zeymer, U.; Desch, S.; Fitzgerald, S. Management of cardiogenic shock. EuroIntervention 2021, 17, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, D.A.; Grines, C.L.; Bailey, S.; Burkhoff, D.; Hall, S.A.; Henry, T.D.; Hollenberg, S.M.; Kapur, N.K.; O’Neil, W.; Ornato, J.P.; et al. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 94, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.D.; Morrow, D.A.; Bohula, E.A. Epidemiology and causes of cardiogenic shock. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2021, 27, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccardi, M.; Metra, M.; Latronico, N.; Mebazaa, A.; Adamo, M.; Cotter, G.; Tomasoni, D.; Chioncel, O.; Gustafsson, F.; Latronico, N.; et al. Medical therapy of cardiogenic shock: Contemporary use of inotropes and vasopressors. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, T.; Sakakura, K.; Sumitsuji, S.; Hyodo, M.; Yamaguchi, J.; Hirase, H.; Yamashita, T.; Kadota, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kozuma, K. Clinical expert consensus document on bailout algorithms for complications in percutaneous coronary intervention from the Japanese Association of Cardiovascular Intervention and Therapeutics. Cardiovasc. Interv. Ther. 2024, 40, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, E.M.; Stouffer, G.A. Bezold-Jarisch Reflex. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2022, 1, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, W.; Tymchak, W.J. Triggering of the Bezold Jarisch Reflex by reperfusion during primary PCI with maintenance of consciousness by cough CPR: A case report and review of pathophysiology. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2008, 20, E239–E242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Y.; Guo, Y.T.; Tian, C.; Song, C.Q.; Mu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.D. Vasovagal reflex syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention: A single-center study. Medicine 2017, 96, e7920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American College of Radiology Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media, Version 2025; American College of Radiology: Reston, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, Y.; Taketomi-Takahashi, A.; Suto, T.; Hirasawa, H.; Tsushima, Y. Clinical features and risk factors of iodinated contrast media (ICM)-induced anaphylaxis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 164, 110880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khatib, S.M.; Stevenson, W.G.; Ackerman, M.J.; Bryant, W.J.; Callans, D.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Deal, B.J.; Dickfeld, T.; Firld, M.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. Circulation 2018, 138, e272–e391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rymer, J.A.; Wegermann, Z.K.; Wang, T.Y.; Li, S.; Smilowitz, N.R.; Wilson, B.H.; Jneid, H.; Tamis-Holland, J.E. Ventricular Arrhythmias After Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for STEMI. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2417835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niccoli, G.; Burzotta, F.; Galiuto, L.; Crea, F. Myocardial no-reflow in humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Zhang, J.J.; Ruan, G.J.; Zhan, Y.Y.; Qiu, A.H.; Ye, M.S.; Xiang, Q.W.; Fang, H.C. Prediction models for no-reflow phenomenon after PCI in acute coronary syndrome patients: A systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 439, 133603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Song, X.; Wang, J.; Dang, Y.; Qi, X. The HALP score predicts no-reflow phenomenon and long-term prognosis in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron. Artery Dis. 2025, 36, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vaidya, Y.; Cavanaugh, S.M.; Dhamoon, A.S. Myocardial Stunning and Hibernation. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Das, J.; Sah, A.K.; Choudhary, R.K.; Elshaikh, R.H.; Bhui, U.; Chowdhury, S.; Abbas, A.M.; Shalabi, M.G.; Siddique, N.A.; Alshammari, R.R.; et al. Network pharmacology approaches to myocardial infarction reperfusion injury: Exploring mechanisms, pathophysiology, and novel therapies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guaricci, A.I.; Bulzis, G.; Pontone, G.; Scicchitano, P.; Carbonara, R.; Rabbat, M.; De Santis, D.; Ciccone, M.M. Current interpretation of myocardial stunning. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 28, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namana, V.; Gupta, S.S.; Abbasi, A.A.; Raheja, H.; Shani, J.; Hollander, G. Right ventricular infarction. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2018, 19 Pt A, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, S.G.; Ajluni, S.; Arnold, A.Z.; Popma, J.J.; Bittl, J.A.; Eigler, N.L.; Cowley, M.J.; Raymond, R.E.; Safian, R.D.; Whitlow, P.L. Increased coronary perforation in the new device era: Incidence, classification, management, and outcome. Circulation 1994, 90, 2725–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimony, A.; Joseph, L.; Mottillo, S.; Eisenberg, M.J. Coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2011, 27, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, C.S.; Kontopantelis, E.; Kinnaird, T.; Potts, J.; Rashid, M.; Shoaib, A.; Nolan, J.; Bagur, R.; de Belder, M.A.; Ludman, P.; et al. Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Temporal Trends, Predictors, and Outcomes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, e005866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwana, J.; Kearney, K.E.; Lombardi, W.L.; Azzalini, L. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of dry tamponade. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 104, 1228–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, L.W.; Korpu, D. Damped and ventricularized coronary pressure waveforms. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2017, 29, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klaudel, J.; Glaza, M.; Klaudel, B.; Trenkner, W.; Pawłowski, K.; Szołkiewicz, M. Catheter-induced coronary artery and aortic dissections: A study of mechanisms, risk factors and propagation causes. Cardiol. J. 2024, 31, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung, R.G.; Stotts, C.; Gupta, A.; Prosperi-Porta, G.; Dhaliwal, S.; Motazedian, P.; Abdel-Razek, O.; Di Santo, P.; Parlow, S.; Belley-Cote, E.; et al. Prognostic Factors Associated with Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, EVIDoa2300323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zweck, E.; Thayer, K.L.; Helgestad, O.K.L.; Kanwar, M.; Ayouty, M.; Garan, A.R.; Hernandez-Montfort, J.; Mahr, C.; Wencker, D.; Sinha, S.S.; et al. Phenotyping Cardiogenic Shock. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Atta, A.; Zaidan, M.; Abdalwahab, A.; Asswad, A.G.; Egred, M.; Zaman, A.; Alkhalil, M. Mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, D.; Jentzer, J.C. Cardiogenic Shock: Pathogenesis, Classification, and Management. Crit. Care Clin. 2024, 40, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alviar, C.L.; Li, B.K.; Keller, N.M.; Bohula-May, E.; Barnett, C.; Berg, D.D.; Burke, J.A.; Chaudhry, S.P.; Daniels, L.B.; DeFilippis, A.P.; et al. CCCTN Investigators. Prognostic performance of the IABP-SHOCK II Risk Score among cardiogenic shock subtypes in the critical care cardiology trials network registry. Am. Heart J. 2024, 270, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thiele, H.; Zeymer, U.; Neumann, F.J.; Ferenc, M.; Olbrich, H.G.; Hausleiter, J.; Richardt, G.; Hennersdof, M.; Empen, K.; Fuernau, G.; et al. IABP-SHOCK II Trial Investigators. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, S.S.; Baran, D.A.; Jentzer, J.C.; Hollenberg, S.M.; van Diepen, S.; Basir, M.B.; Grines, C.L.; Diercks, D.B.; Hall, S.; Kapur, N.K.; et al. SCAI SHOCK Stage Classification Expert Consensus Update. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochman, J.S.; Sleeper, L.A.; Webb, J.G.; Sanborn, T.A.; White, H.D.; Talley, J.D.; Buller, C.E.; Jacobs, A.K.; Slater, J.N.; Dol, J.; et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochman, J.S.; Sleeper, L.A.; Webb, J.G.; Dzavik, V.; Buller, C.E.; Aylward, P.; Col, J.; White, H.D. SHOCK Investigators. Early revascularization and long-term survival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2006, 295, 2511–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, K.H.; Maier, S.K.G.; Maier, L.S.; Lengenfelder, B.; Jacobshagen, C.; Jung, J.; Fleischmann, C.; Werner, G.S.; Olbrich, H.G.; Ott, R.; et al. Impact of treatment delay on mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients presenting with and without haemodynamic instability: Results from the German prospective, multicentre FITT-STEMI trial. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thiele, H.; Akin, I.; Sandri, M.; Fuernau, G.; De Waha, S.; Meyer-Saraei, R.; Nordbeck, P.; Geisler, T.; Landmesser, U.; Skurk, C.; et al. PCI Strategies in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2419–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, H.; Akin, I.; Sandri, M.; De Waha-Thiele, S.; Meyer-Saraei, R.; Fuernau, G.; Eitel, I.; Nordbeck, P.; Geisler, T.; Landmesser, U.; et al. One-Year Outcomes after PCI Strategies in Cardiogenic Shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damluji, A.A.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Berkower, C.; Boyd, C.M.; Al-Damluji, M.S.; Cohen, M.G.; Forman, D.E.; Chaudhary, R.; Gerstenblith, G.; Walston, J.D.; et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Older Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barthélémy, O.; Rouanet, S.; Brugier, D.; Vignolles, N.; Bertin, B.; Zeitouni, M.; Guedeney, P.; Hauguel-Moreau, M.; Hage, G.; Overtchouk, P.; et al. Predictive Value of the Residual SYNTAX Score in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Alviar, C.L.; Katz, S.D.; Hochman, J.S. Coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Am. Heart J. 2020, 226, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Viana-Tejedor, A.; Fernández-Ortiz, A.; Fernández-Avilés, F.; Gutiérrez-Ibanes, E.; Macaya, C.; Ibáñez, B.; Sánchez-Brunete, V.; Galeote, G.; Gómez-Hernández, A.; Pérez de Prado, A.; et al. Culprit-Only versus Immediate Multivessel Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart 2018, 104, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basir, M.B.; Kapur, N.K.; Patel, K.; Salam, M.A.; Schreiber, T.; Kaki, A.; Hanson, I.; Almany, S.; Timmis, S.; Dixon, S.; et al. Improved outcomes associated with the use of shock protocols: Updates from the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 93, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, H.; Zeymer, U.; Thelemann, N.; Neumann, F.J.; Hausleiter, J.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Fuernau, G.; Eitel, I.; Hambrecht, R.; Böhm, M.; et al. Long-Term 6-Year Outcome of the Randomized IABP-SHOCK II Trial. Circulation. 2019, 139, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouweneel, D.M.; Eriksen, E.; Sjauw, K.D.; van Dongen, I.M.; Hirsch, A.; Packer, E.J.; Vis, M.M.; Wykrzykowska, J.J.; Koch, K.T.; de Winter, R.J.; et al. Impella CP versus intra-aortic balloon pump in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: The IMPRESS trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouweneel, D.M.; Eriksen, E.; Sjauw, K.D.; van Dongen, I.M.; Hirsch, A.; Packer, E.J.; Vis, M.M.; Wykrzykowska, J.J.; Koch, K.T.; Baan, J., Jr.; et al. Long-Term 5-Year Outcome of the Randomized IMPRESS in Severe Shock Trial. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care. 2021, 10, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thiele, H.; Sick, P.; Boudriot, E.; Diederich, K.W.; Hambrecht, R.; Niebauer, J.; Schuler, G. Randomized comparison of intra-aortic balloon support versus a percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with revascularized acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 1276–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhoff, D.; Cohen, H.; Brunckhorst, C.; O’Neill, W.W.; TandemHeart Investigators. A randomized multicenter clinical study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device versus conventional therapy with intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock. Am. Heart J. 2006, 152, e1–e469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schmidt, M.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Kaltoft, A.; Helqvist, S.; Saunamäki, K.; Nielsen, P.H.; Ravn, H.B.; Terkelsen, C.J.; Madsen, M.; Lassen, J.F.; et al. DanGer Shock Investigators. Mechanical circulatory support with Impella CP in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thiele, H.; Zeymer, U.; Thelemann, N.; Neumann, F.J.; Hausleiter, J.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Meyer-Saraei, R.; Fuernau, G.; Pöss, J.; Desch, S.; et al. ECLS-SHOCK Investigators. Extracorporeal life support in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostadal, P.; Rokyta, R.; Karasek, J.; Kruger, A.; Vondrakova, D.; Janotka, M.; Naar, J.; Smalcova, J.; Hubatova, M.; Hromadka, M.; et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the therapy of cardiogenic shock: Results of the ECMO-CS randomized clinical trial. Circulation 2023, 147, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostadal, P.; Rokyta, R.; Karasek, J.; Kruger, A.; Vondrakova, D.; Janotka, M.; Naar, J.; Smalcova, J.; Hubatova, M.; Hromadka, M.; et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the therapy of cardiogenic shock: 1-year outcomes of the multicentre, randomized ECMO-CS trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2025, 27, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rihal, C.S.; Naidu, S.S.; Givertz, M.M.; Szeto, W.Y.; Burke, J.A.; Kapur, N.K.; Kern, M.; Garratt, K.N.; Goldstein, J.A.; Dimas, V.; et al. 2015 SCAI/ACC/HFSA/STS Clinical Expert Consensus Statement on the Use of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiovascular Care: Endorsed by the American Heart Assocation, the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologia Intervencion; Affirmation of Value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologie d’intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, e7–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putowski, Z.; Pluta, M.P.; Rachfalska, N.; Krzych, Ł.J.; De Backer, D. Sublingual Microcirculation in Temporary Mechanical Circulatory Support: A Current State of Knowledge. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2023, 37, 2065–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banning, A.S.; Sabaté, M.; Orban, M.; Gracey, J.; López-Sobrino, T.; Massberg, S.; Kastrati, A.; Bogaerts, K.; Adriaenssens, T.; Berry, C.; et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or standard care in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: The multicentre, randomised EURO SHOCK trial. EuroIntervention 2023, 19, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouweneel, D.M.; Schotborgh, J.V.; Limpens, J.; Sjauw, K.D.; Engström, A.E.; Lagrand, W.K.; Cherpanath, T.G.V.; Driessen, A.H.; de Mol, B.A.J.; Henriques, J.P.S. Extracorporeal life support during cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 231, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burzotta, F.; Trani, C.; Doshi, S.N.; Townend, J.; van Geuns, R.J.; Hunziker, P.; Shieffer, B.; Karatolios, K.; Moller, J.E.; Ribichini, F.L.; et al. Impella ventricular support in clinical practice: Collaborative viewpoint from a European expert user group. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 201, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrage, B.; Becher, P.M.; Bernhardt, A.; Bezerra, H.; Blankenberg, S.; Brunner, S.; Colson, P.; Deseda, G.C.; Dabboura, S.; Eckner, D.; et al. Left ventricular unloading is associated with lower mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock treated with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Results from an international, multicenter cohort study. Circulation 2020, 142, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.B.; Goldstein, J.; Milano, C.; Morris, L.D.; Kormos, R.L.; Bhama, J.; Kapur, N.K.; Bansal, A.; Garcia, J.; Baker, J.N.; et al. Benefits of a novel percutaneous ventricular assist device for right heart failure: The prospective RECOVER RIGHT study of the Impella RP device. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfarth, M.; Sibbing, D.; Bauer, I.; Fröhlich, G.; Bott-Flügel, L.; Byrne, R.; Dirschinger, J.; Kastrati, A.; Schömig, A. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1584–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, D.; Byrne, J.; Rathod, K.; Jain, A.K.; Ludman, P.F.; Williams, I.M.; Bogle, R.G.; Whitbourn, R.; Lim, H.S.; Kharbanda, R.; et al. CHIP-BCIS3 (Randomized Trial of Elective Insertion of Percutaneous Left Ventricular Support Device [Impella] in High-Risk PCI). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05003817. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05003817 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- PROTECT IV (Impella Support in High-Risk PCI). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04763200. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04763200 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- O’Neill, W.W.; Kleiman, N.S.; Moses, J.; Henriques, J.P.; Dixon, S.; Massaro, J.; Palacios, I.; Maini, B.; Muilukutla, S.; Džavík, V.; et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing high-risk PCI: The PROTECT II study. Circulation 2012, 126, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).