Damage Control Surgery in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Abdomino-Pelvic Packing in Multimodal Hemorrhage Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. History of Abdomino-Pelvic Packing

3. Physiological Basis and Core Principles of DCS in OB/GYN

- Coagulopathy in this context is typically diffuse and non-mechanical (oozing from raw surfaces and venous plexuses) [65]. The diagnosis of coagulopathy is mainly clinical by observing generalized non-surgical bleeding from wounds, vascular access sites and others. Laboratory tests do not always confirm coagulopathy in critically injured patients. While abnormalities in standard labs (e.g., prolonged PT/aPTT, thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia) can support the diagnosis, clinical judgment remains central because conventional tests may not be immediately available, and—even when available—may fail to reflect real-time or clinically significant coagulopathy in critically injured patients [25,66,71,72].

- Massive transfusion requirements (e.g., ≥10 units PRBC or ≥5000 mL blood products within 24 h);

- Persistent hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg) despite active resuscitation;

- Severe metabolic derangement (e.g., pH < 7.2, base deficit > 8 mEq/L);

- Hypothermia (<35 °C) and clinical coagulopathy (diffuse bleeding);

- Depressed sensorium (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale decline) as a global hypoperfusion marker in hemorrhagic shock.

- Excessive intraoperative fluid/blood product replacement (e.g., >12,000 mL crystalloids/blood products);

- Prolonged operative time in an unstable patient (e.g., >90 min without clear hemostatic control);

- High injury burden (e.g., ISS > 35) or combined injuries (major abdominal vascular and visceral injuries);

- Pelvic trauma with major vascular involvement;

- Inability to achieve tension-free primary fascial closure due to edema/packing, mandating temporary closure.

- 1.

- Abbreviated laparotomy focused solely on hemostasis (e.g., APP, rapid vascular control);

- 2.

- Temporary closure to allow for re-exploration;

- 3.

- Intensive care unit (ICU) resuscitation to reverse hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy;

- 4.

- Planned reoperation for pack removal and definitive repair once physiological stability is achieved.

4. Topographic Typology of Packings in OB/GYN

- Vaginal packing—This is primarily used for persistent vaginal or cervical bleeding, such as from lacerations, episiotomy sites, or cervical tears occurring during childbirth or in the postoperative period. This technique remains relevant as a first-line mechanical tamponade for focal bleeding and is supported by its inclusion in recommended interventions for postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) [47]. Vaginal packing is not recommended in cases of PPH resulting from uterine atony [2].

- Uterovaginal packing—This is traditionally applied in managing PPH secondary to uterine atony when pharmacological and other first-line methods fail. While classic gauze packing was historically standard, its use is increasingly supplanted or augmented by intrauterine balloon tamponade devices (e.g., Bakri balloon, condom catheter), which offer more controlled and quantifiable pressure with reduced risks of infection and migration [47]. Recent reviews highlight the role of these devices in reducing the need for surgical escalation [39].

- Vagino-pelvic packing—This is indicated for uncontrolled pelvic bleeding after hysterectomy, especially when retroperitoneal hemorrhage or bleeding from the vaginal cuff is suspected. The technique, often referred to as Logothetopulos packing after its initial description in 1926, involves retrograde placement of sterile packs through the vaginal vault into the pelvic cavity to achieve tamponade of deep vascular structures or diffuse oozing surfaces [38,63].

- Pelvic packing—This is performed directly within the pelvic cavity via laparotomy to control diffuse venous oozing, arterial bleeding from parametrial dissection, or injury to branches of the internal iliac system. Variants such as the “Mikulicz technique” involve layered placement of laparotomy pads to maximize compression against the bony pelvis and fascial planes [9,10,11]. This approach is documented in case series involving gynecologic oncology procedures, where rapid hemorrhage control is critical [9].

- Abdominal packing—This is utilized for uncontrolled hemorrhage originating in the upper or middle abdomen, such as from liver or splenic injury, major vascular lesions, or diffuse peritoneal bleeding during extensive oncologic resections. Though less frequently required in pure gynecologic cases, it has been described in the context of advanced cytoreductive or exenterative surgery [37,39].

5. Decision-Making, Indications, and Contraindications for DCS in OB/GYN

5.1. Obstetric Indications

- Resource-limited settings lacking blood products or interventional radiology [4].

5.2. Gynecological Indications

5.3. Clinical Decision-Making and Contraindications for DCS and APP

- Non-survivable injuries (e.g., non-survivable traumatic brain injury, metastatic disease with catastrophic bleed) or patient-specific factors such as advance directives favoring comfort care. DCS is a life-preserving strategy, not a substitute for thoughtful goals-of-care discussions.

- Uncontrolled bleeding from major central vessels (e.g., abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava) where effective tamponade cannot be achieved with packing alone.

- Uncontrolled infection in the operative field (e.g., perforated viscus with purulent contamination) that may preclude temporary closure and increase sepsis risk.

- Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) without a decompression plan, as packing can exacerbate intra-abdominal hypertension.

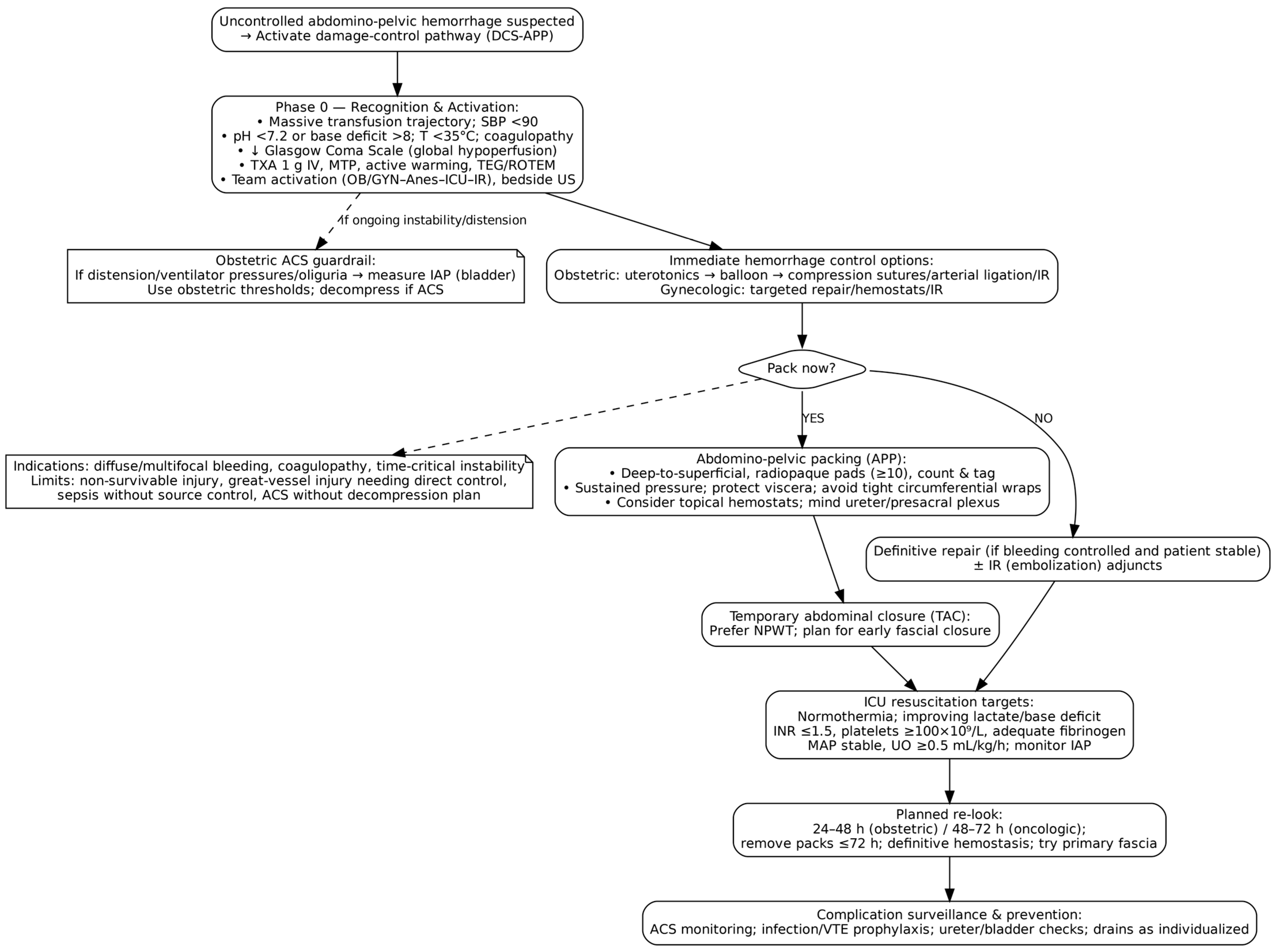

6. Evidence-Based DCS Protocol in OB/GYN

6.1. Phase 0/Ground Zero: Preoperative Resuscitation and Team Activation

6.1.1. Multidisciplinary Team Assembly

6.1.2. Hemostatic Optimization

6.1.3. Volume and Pressure Management

6.1.4. Temperature Management

6.1.5. Laboratory and Point-of-Care Monitoring

6.2. Phase I: Abbreviated Surgical Control and Packing

6.2.1. Surgical Access and Exploration

6.2.2. Contamination Control

6.2.3. Decision to Pack vs. Repair

- Multiple or diffuse bleeding sites (presacral venous plexus, parametrial oozing);

- Hemodynamic instability unlikely to tolerate prolonged surgery;

- Coagulopathy limiting surgical hemostasis;

- Anatomically challenging bleeding areas (retroperitoneum, deep pelvis);

- Persistent bleeding after hysterectomy or internal iliac artery ligation;

6.2.4. Modern Packing Technique

- Material selection: Use large, radiopaque laparotomy pads (minimum 7–10, preferably 10–12). Smaller pads risk being lost during removal, especially after 48 h.

- Accountability: Pads should be tied together and strictly counted to ensure complete retrieval.

- Visceral protection: Interpose bowel bags between packing and viscera to prevent adhesions. Consider omentum interposition over raw surfaces when feasible. Ureters should be identified or presumed present in high-risk zones [29].

6.2.5. Temporary Abdominal Closure

- Skin closure with clips or sutures: Rapid, inexpensive, and easily available, but associated with a high risk of evisceration, infection, recurrent intra-abdominal hypertension, and poor outcomes. These techniques are no longer favored due to high complication and mortality rates.

- Mesh closure and dynamic retention sutures: Meshes (absorbable or non-absorbable) provide a barrier and allow gradual fascial closure but carry a risk of hernia, infection, and adhesions. Dynamic retention sutures help prevent fascial retraction, supporting delayed closure, but are technically demanding and associated with high hernia risk.

- Wittmann Patch (Artificial Burr): This Velcro-like patch enables progressive, staged closure of the abdomen with high rates of primary fascial closure (75–90%). It facilitates repeated re-entries, preserves domain, and is particularly helpful for patients needing multiple operations, though it is costly and does not effectively evacuate peritoneal fluid.

- Bogota Bag: Inexpensive and quickly applied using a sterile irrigation bag sewn to the fascia or skin, it serves as a “non-traction” technique suitable for resource-poor settings. However, it can permit fascial retraction and loss of domain, carries a higher risk of infection and fistula, and is associated with lower closure rates.

- Barker Vacuum Pack: This involves covering the viscera with a polyethylene sheet, then towels and an adhesive drape, and using a suction drain for negative pressure. It is simple and affordable, and, while still used in resource-limited settings, has been largely surpassed by commercial NPT systems because of inferior outcomes in terms of closure rates and complications.

- Commercial Negative Pressure Therapy (NPT) Systems: Devices like 3M™ AbThera™ Therapy are specifically designed for open abdomen management. These systems provide continuous negative pressure, facilitate fluid removal, preserve abdominal domain, and promote fascial approximation. They offer superior closure rates, reduced mortality, and better clinical outcomes; thus, they are the preferred technique according to most guidelines when available, though cost and access may be limiting factors [91].

6.3. Phase II: Critical Care Resuscitation

6.3.1. Primary Resuscitation Targets

- Temperature: Maintaining core > 36 °C with active warming.

- Acid–base balance: Targeting pH > 7.25 and base deficit < 4 mEq/L. Avoidance of routine bicarbonate use unless pH < 7.1.

- Coagulation: Target values for fibrinogen are >200 mg/dL (supplement with fibrinogen concentrate if <150 mg/dL), PT/PTT < 1.5× normal, and platelets > 75,000/μL [72].

6.3.2. Monitoring and Complication Prevention

- Drain output: Should decrease to <200 mL/hour after coagulopathy correction. Re-laparotomy may be indicated if output exceeds 400 mL/hour in a coagulopathic patient [25].

- Neurological and pain management: Adequate sedation and analgesia are essential, particularly in prolonged ICU stays.

- Enteral feeding: Early enteral nutrition (EN) is associated with fewer infections and higher fascial closure rates [94]. Parenteral nutrition should be initiated started promptly when EN is not feasible. As soon as hemodynamic resuscitation is largely complete and intestinal viability is confirmed, EN should be initiated. A relative contraindication to EN is a viable bowel remnant < 75 cm [95].

- Thromboprophylaxis: Mechanical prophylaxis during coagulopathy; pharmacological after correction [72].

- Antibiotic prophylaxis: In trauma, broad-spectrum antibiotics are standard due to hollow viscus injury. In OB/GYN, an optimal antibiotic prophylaxis is debatable. Usually, second-generation cephalosporins +/− metronidazole are recommended until definitive repair; aminoglycosides should be avoided due to nephrotoxicity and ototoxity [27].

6.4. Phase II: Definitive Reconstruction

6.4.1. Timing of Re-Laparotomy

- Obstetric cases: 24–48 h, as bleeding is typically venous or capillary and stabilizes earlier [7].

- The timeframe of 72 h should never be exceeded, as infection risk increases exponentially beyond this point.

6.4.2. Readiness Criteria

- Temperature: core temperature ≥ 36 °C (normothermia achieved). Earlier recommendation for at least >6 h at >36 °C seems arbitrary; trend and stability matter more than time box [96].

- Coagulation: INR ≤ 1.5, platelets ≥ 100 × 109/L, fibrinogen adequate (many centers target ≥ 2.0 g/L), with no active diffuse coagulopathic oozing [69].

- Hemodynamics: stable MAP with minimal or no vasopressor support and adequate urine output (≥0.5 mL/kg/h), indicating restored end-organ perfusion. IAP < 15 mmHg is a reasonable safety boundary for closure (IAH is ≥12 mmHg; ACS is >20 mmHg with new organ dysfunction) but should be combined with overall abdominal compliance/closure feasibility [69].

- Transfusion trajectory: no ongoing massive transfusion requirement and blood product use clearly decelerating (many teams use “≤2 units over 4–6 h” pragmatically, though not formally guideline-mandated) [69].

- There is no validated abdominal drain-output threshold, which is congruent with overall weak evidence for routine drainage in surgery. Some sources recommend removing drains when output is <200 mL/h, but the individual threshold should be seen in context of injury pattern, TAC technique, patient hemodynamics, and feasibility of safe closure instead [78,95].

6.4.3. Pack Removal and Definitive Hemostasis

- Preparation: Full surgical team, anesthesia with muscle relaxation, blood products at bedside, and setup for re-packing if needed.

- Technique: Irrigate the field with warm saline before removal. Remove packs slowly and systematically, applying counter-pressure. Inspect each anatomical zone for residual bleeding.

- Definitive control: Address active bleeding with sutures, clips, or vessel ligation. Use hemostatic agents as adjuncts.

- Closure: After copious irrigation, attempt primary fascial closure if possible—achieved in 60–80% of cases. If not, use NPT or planned skin grafting.

7. Complications and Outcomes of DCS in OB/GYN

7.1. Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS)

- Non-surgical measures: nasogastric or rectal decompression, gastrointestinal prokinetics, diuretics, and neuromuscular blockade to reduce intra-abdominal volume and abdominal wall tone.

- Surgical decompression: indicated when medical management fails and organ dysfunction persists; may involve opening a closed fascia, loosening or removing packs (with potential risk of re-bleeding), or extending the abdominal incision [27].

7.2. Infectious Complications

7.3. Urological Complications

7.4. Vascular Complications

7.5. Outcomes of APP/DCS

7.5.1. Short-Term Outcomes

7.5.2. Long-Term Outcomes

7.5.3. Key Factors for Optimal Outcomes

- Early intervention before the lethal triad (hypothermia, acidosis, coagulopathy) becomes established.

- Appropriate patient selection.

- Multidisciplinary team experience (gynecology/obstetrics, anesthesia/critical care, interventional radiology, vascular/urology).

- Integration of modern hemostatic strategies (TXA, topical hemostats, embolization).

- Strict aseptic technique.

- Timely pack removal (24–48 h, obstetric; 48–72 h, oncologic).

- Comprehensive postoperative monitoring and support (infection surveillance, DVT prophylaxis when safe, nutrition/physiotherapy, psychological support).

7.6. Special Considerations in Gynecologic Oncology

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cresswell, J.A.; Alexander, M.; Chong, M.Y.C.; Link, H.M.; Pejchinovska, M.; Gazeley, U.; Ahmed, S.M.A.; Chou, D.; Moller, A.-B.; Simpson, D.; et al. Global and Regional Causes of Maternal Deaths 2009–20: A WHO Systematic Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e626–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, M.F.; Nassar, A.H.; Theron, G.; Barnea, E.R.; Nicholson, W.; Ramasauskaite, D.; Lloyd, I.; Chandraharan, E.; Miller, S.; Burke, T.; et al. FIGO Recommendations on the Management of Postpartum Hemorrhage 2022. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2022, 157 (Suppl. 1), 3–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.D.; Ananth, C.V.; Lewin, S.N.; Burke, W.M.; Siddiq, Z.; Neugut, A.I.; Herzog, T.J.; Hershman, D.L. Patterns of Use of Hemostatic Agents in Patients Undergoing Major Surgery. J. Surg. Res. 2014, 186, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, A.; Kavya, H.S.; Nandanwar, Y.S.; Ansari, A. Pelvic Pressure Packing for Intractable Obstetric and Gynaecological Hemorrhage in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 7, 4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.P.; Cohen, J.G.; Parker, W.H. Management of Hemorrhage During Gynecologic Surgery. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 58, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Abraham, A.; Regi, A. Clinical Perspective: Caesarean Hysterectomy for Placenta Accreta Spectrum and Role of Pelvic Packing. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 8, 4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffieux, X.; Vinchant, M.; Wigniolle, I.; Goffinet, F.; Sentilhes, L. Maternal Outcome after Abdominal Packing for Uncontrolled Postpartum Hemorrhage despite Peripartum Hysterectomy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buras, A.L.; Chern, J.Y.; Chon, H.S.; Shahzad, M.M.; Wenham, R.M.; Hoffman, M.S. Major Vascular Injury During Gynecologic Cancer Surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 37, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, J.B.; Karmakar, D.; Roy, K.K.; Singh, N. Combined Intra-Abdominal Pelvic Packing During Cytoreductive Surgery in Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Case Series. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 285, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finan, M.A.; Fiorica, J.V.; Hoffman, M.S.; Barton, D.P.; Gleeson, N.; Roberts, W.S.; Cavanagh, D. Massive Pelvic Hemorrhage During Gynecologic Cancer Surgery: “Pack and Go Back”. Gynecol. Oncol. 1996, 62, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wydra, D.; Emerich, J.; Ciach, K.; Dudziak, M.; Marciniak, A. Surgical Pelvic Packing as a Means of Controlling Massive Intraoperative Bleeding During Pelvic Posterior Exenteration–A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2004, 14, 1050–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrowski, R.; Kostov, S.; Alkatout, I. Complications in Laparoscopic and Robotic-Assisted Surgery: Definitions, Classifications, Incidence and Risk Factors-an up-to-Date Review. Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2021, 16, 501–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, W.R. Hysterectomy, Massive Transfusion and Packing to Control Haemorrhage from Pelvic Veins in the Course of Bilateral Oophorectomy. Aust. New Zealand J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1996, 36, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivalingam, N.; Rajesvaran, D. Coital Injury Requiring Internal Iliac Artery Ligation. Singap. Med. J. 1996, 37, 547–548. [Google Scholar]

- Jeng, C.-J.; Wang, L.-R. Vaginal Laceration and Hemorrhagic Shock during Consensual Sexual Intercourse. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2007, 33, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, H.; Bambury, I.; Williams, M. Post-Coital Posterior Fornix Perforation with Peritonitis and Haemoperitoneum. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2013, 4, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, R.E.; Zahurak, M.L.; Diaz-Montes, T.P.; Giuntoli, R.L.; Armstrong, D.K. Impact of Surgeon and Hospital Ovarian Cancer Surgical Case Volume on In-Hospital Mortality and Related Short-Term Outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 115, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, L.; Casarin, J.; Mara, K.C.; Weaver, A.L.; Multinu, F.; Glaser, G.E.; Cliby, W.A.; Scambia, G.; Mariani, A.; Kumar, A. Prediction of Short-Term Surgical Complications in Women Undergoing Pelvic Exenteration for Gynecological Malignancies. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 152, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortorella, L.; Marco, C.; Loverro, M.; Carmine, C.; Persichetti, E.; Bizzarri, N.; Barbara, C.; Francesco, S.; Foschi, N.; Gallotta, V.; et al. Predictive Factors of Surgical Complications after Pelvic Exenteration for Gynecological Malignancies: A Large Single-Institution Experience. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 35, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, M.F.; Schwab, C.W.; McGonigal, M.D.; Phillips, G.R.; Fruchterman, T.M.; Kauder, D.R.; Latenser, B.A.; Angood, P.A. “Damage Control”: An Approach for Improved Survival in Exsanguinating Penetrating Abdominal Injury. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1993, 35, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, K.W.; Locicero, R.J. Abdominal Packing for Surgically Uncontrollable Hemorrhage. Ann. Surg. 1992, 215, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.W.; Gracias, V.H.; Schwab, C.W.; Reilly, P.M.; Kauder, D.R.; Shapiro, M.B.; Dabrowski, G.P.; Rotondo, M.F. Evolution in Damage Control for Exsanguinating Penetrating Abdominal Injury. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2001, 51, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaunoo, S.S.; Harji, D.P. Damage Control Surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2009, 7, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikoulis, E.; Salem, K.M.; Avgerinos, E.D.; Pikouli, A.; Angelou, A.; Pikoulis, A.; Georgopoulos, S.; Karavokyros, I. Damage Control for Vascular Trauma from the Prehospital to the Operating Room Setting. Front. Surg. 2017, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waibel, B.H.; Rotondo, M.M. Damage Control Surgery: It’s Evolution over the Last 20 Years. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 2012, 39, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awonuga, A.O.; Merhi, Z.O.; Khulpateea, N. Abdominal Packing for Intractable Obstetrical and Gynecologic Hemorrhage. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2006, 93, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, L.D.; Lozada, M.J.; Saade, G.R.; Hankins, G.D.V. Damage-Control Surgery for Obstetric Hemorrhage. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvajal, J.A.; Ramos, I.; Kusanovic, J.P.; Escobar, M.F. Damage-Control Resuscitation in Obstetrics. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingold, J.A.; Falcone, T. Retroperitoneal Anatomy during Excision of Pelvic Side Wall Endometriosis. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2016, 8, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrowski, R.; Jäger, C.; Forster, J. Improvement of Perioperative Outcomes in Major Gynecological and Gynecologic–Oncological Surgery with Hemostatic Gelatin–Thrombin Matrix. In Vivo 2017, 31, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.V.; Mattox, K.L.; Burch, J.M.; Bitondo, C.G.; Jordan, G.L. Packing for Control of Hepatic Hemorrhage. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1986, 26, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, C.; Pino, L.; Badiel, M.; Sanchez, A.; Loaiza, J.; Ramirez, O.; Rosso, F.; García, A.; Granados, M.; Ospina, G.; et al. The 1-2-3 Approach to Abdominal Packing. World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, A.L.; Miller, A. Managing Severe (and Open) Pelvic Disruption. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2025, 10, e001820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-S.; Zhou, S.-G.; He, L.-S.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Zhang, X.-M. The Effect of Preperitoneal Pelvic Packing for Hemodynamically Unstable Patients with Pelvic Fractures. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, R.J.; Straughn, J.M.; Huh, W.K.; Rouse, D.J. Pelvic Umbrella Pack for Refractory Obstetric Hemorrhage Secondary to Posterior Uterine Rupture. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 100, 1061–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dildy, G.A.; Scott, J.R.; Saffer, C.S.; Belfort, M.A. An Effective Pressure Pack for Severe Pelvic Hemorrhage. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoong, W.; Lavina, A.; Ali, A.; Sivashanmugarajan, V.; Govind, A.; McMonagle, M. Abdomino-Pelvic Packing Revisited: An Often Forgotten Technique for Managing Intractable Venous Obstetric Haemorrhage. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Gutiérrez, L.A.; Oliva-Cristerna, J.; Ramírez-Montiel, M.L.; Ortiz, M.I. Pelvic Packing with Vaginal Traction for the Management of Intractable Hemorrhage. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 127, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winata, I.G.S.; Asmara, A.D. Abdominal Packing for Obstetric Surgical Uncontrollable Hemorrhage. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 4, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhami, O.; Bouzid, A.; Ben Marzouk, S.; Kehila, M.; Channoufi, M.B.; El Magherbi, H. Pelvic Packing for Intractable Obstetric Hemorrhage After Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy: A Review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2018, 73, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhami, O.; Marzouk, S.B.; Kehila, M.; Bennasr, L.; Fezai, A.; Channoufi, M.B.; Magherbi, H.E. Efficacy and Safety of Pelvic Packing after Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy (EPH) in Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) Setting. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 202, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braley, S.C.; Schneider, P.D.; Bold, R.J.; Goodnight, J.E.; Khatri, V.P. Controlled Tamponade of Severe Presacral Venous Hemorrhage: Use of a Breast Implant Sizer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2002, 45, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıççı, Ç.; Polat, M.; Küçükbaş, M.; Şentürk, M.B.; Karakuş, R.; Yayla Abide, Ç.; Bostancı Ergen, E.; Yenidede, İ.; Karateke, A. Modified Abdominal Packing Method in “near Miss” Patients with Postpartum Hemorrhages. Turk. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 15, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueckelmann, A.M.; Hinkson, L.; Guggenberger, M.; Braun, T.; Henrich, W. Safety and Efficacy of the Chitosan Covered Tamponade for the Management of Lower Genital Tract Trauma during Childbirth. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2025, 38, 2511092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.A.; Bhayani, S.B.; Kavoussi, L.R. Laparoscopic Temporary Packing for Hemostasis. Urology 2005, 66, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.; Wright, J.D. Surgical Intervention in the Management of Postpartum Hemorrhage. Semin. Perinatol. 2009, 33, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellie, F.J.; Wandabwa, J.N.; Mousa, H.A.; Weeks, A.D. Mechanical and Surgical Interventions for Treating Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 7, CD013663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, A.M.; Sikorski, M.J.; Kofinas, P. Hemostatic Strategies for Traumatic and Surgical Bleeding. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2014, 102, 4182–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of Early Tranexamic Acid Administration on Mortality, Hysterectomy, and Other Morbidities in Women with Post-Partum Haemorrhage (WOMAN): An International, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, A.; Shakur-Still, H.; Chaudhri, R.; Fawole, B.; Arulkumaran, S.; Roberts, I.; WOMAN Trial Collaborators. The Impact of Early Outcome Events on the Effect of Tranexamic Acid in Post-Partum Haemorrhage: An Exploratory Subgroup Analysis of the WOMAN Trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, K.; Sentilhes, L.; Shakur-Still, H.; Madar, H.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Saade, G.; Pacheco, L.D.; Ageron, F.-X.; Mansukhani, R.; Balogun, E.; et al. Tranexamic Acid for Postpartum Bleeding: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Lancet 2024, 404, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRASH-2 trial collaborators; Shakur, H.; Roberts, I.; Bautista, R.; Caballero, J.; Coats, T.; Dewan, Y.; El-Sayed, H.; Gogichaishvili, T.; Gupta, S.; et al. Effects of Tranexamic Acid on Death, Vascular Occlusive Events, and Blood Transfusion in Trauma Patients with Significant Haemorrhage (CRASH-2): A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.G.M.; Solomon, M.J. Topical Haemostatic Agents in Surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111, znad361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watrowski, R. Hemostatic Gelatine-Thrombin Matrix (Floseal®) Facilitates Hemostasis and Organ Preservation in Laparoscopic Treatment of Tubal Pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 290, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrowski, R.; Lange, A.; Möckel, J. Primary Omental Pregnancy with Secondary Implantation into Posterior Cul-de-Sac: Laparoscopic Treatment Using Hemostatic Matrix. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watrowski, R. Unifying Local Hemostasis and Adhesion Prevention during Gynaecologic Laparoscopies: Experiences with a Novel, Plant-Based Agent. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 586–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmer, A.R.; Aslancan, R.; Teymen, B.; Çalışkan, E. External Iliac Artery Thrombosis after Hypogastric Artery Ligation and Pelvic Packing for Placenta Previa Percreta. Turk. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 15, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, S.; Kornovski, Y.; Watrowski, R.; Slavchev, S.; Ivanova, Y.; Yordanov, A. Internal Iliac Artery Ligation in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Surgical Anatomy and Surgical Considerations. Clin. Pract. 2023, 14, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, K.; Tolikas, A.; Dovas, D.; Fragkedakis, N.; Koutsos, J.; Giannoylis, C.; Tzafettas, J. Ligation of Internal Iliac Artery for Severe Obstetric and Pelvic Haemorrhage: 10 Year Experience with 11 Cases in a University Hospital. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 28, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, Y.; Pang, C.L. Endovascular Interventional Modalities for Haemorrhage Control in Abnormal Placental Implantation Deliveries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 2713–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Gong, X.; Wang, N.; Mu, K.; Feng, L.; Qiao, F.; Chen, S.; Zeng, W.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; et al. A Prospective Observational Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Prophylactic Internal Iliac Artery Balloon Catheterization in the Management of Placenta Previa-Accreta: A STROBE Compliant Article. Medicine 2017, 96, e8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, J.H. Notes on the Arrest of Hepatic Hemorrhage Due to Trauma. Ann. Surg. 1908, 48, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logothetopoulos, K. Eine absolut sichere Blutstillungsmethode bei vaginalen und abdominalen gynäkologischen Operationen. [An absolutely certainmethod of stopping bleeding during abdominal and vaginal operations]. Zentralbl Gynäkol 1926, 50, 3202–3204. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C.E.; Ledgerwood, A.M. Prospective Evaluation of Hemostatic Techniques for Liver Injuries. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1976, 16, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, H.H.; Strom, P.R.; Mullins, R.J. Management of the Major Coagulopathy with Onset during Laparotomy. Ann. Surg. 1983, 197, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burch, J.M.; Ortiz, V.B.; Richardson, R.J.; Martin, R.R.; Mattox, K.L.; Jordan, G.L. Abbreviated Laparotomy and Planned Reoperation for Critically Injured Patients. Ann. Surg. 1992, 215, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashuk, J.L.; Moore, E.E.; Millikan, J.S.; Moore, J.B. Major Abdominal Vascular Trauma—A Unified Approach. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1982, 22, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurkovich, G.J.; Greiser, W.B.; Luterman, A.; Curreri, P.W. Hypothermia in Trauma Victims: An Ominous Predictor of Survival. J. Trauma 1987, 27, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossaint, R.; Afshari, A.; Bouillon, B.; Cerny, V.; Cimpoesu, D.; Curry, N.; Duranteau, J.; Filipescu, D.; Grottke, O.; Grønlykke, L.; et al. The European Guideline on Management of Major Bleeding and Coagulopathy Following Trauma: Sixth Edition. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Mascha, E.; Na, J.; Sessler, D.I. The Effects of Mild Perioperative Hypothermia on Blood Loss and Transfusion Requirement. Anesthesiology 2008, 108, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, G.S.; Sexton, K.W.; Beck, W.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Bhavaraju, A.; Davis, B.; Kimbrough, M.K.; Jensen, J.C.; Privratsky, A.; Robertson, R.D. Characterization of Acidosis in Trauma Patient. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock 2020, 13, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C.L.; Brohi, K.; Curry, N.; Juffermans, N.P.; Mora Miquel, L.; Neal, M.D.; Shaz, B.H.; Vlaar, A.P.J.; Helms, J. Contemporary Management of Major Haemorrhage in Critical Care. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos Rodríguez, A.L. The Obstetrician Attached to the Obstetric Emergency. Colomb. Med. 2024, 55, e3006574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma-Pillay, P.; Nelson-Piercy, C.; Tolppanen, H.; Mebazaa, A. Physiological Changes in Pregnancy. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2016, 27, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzi, A.A.; Sulaimani, M. Damage-Control Surgery for Maternal Near-Miss Cases of Placenta Previa and Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Int. J. Women’s Health 2021, 13, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawanpaiboon, S.; Janchua, M.; Luamprapat, P.; Chawanpaiboon, P.; Maimaen, S. Managing Life-Threatening Spontaneous Liver Rupture in Pregnancy: A Case Study. Am. J. Case Rep. 2025, 26, e946909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Rani, J. Hepatic Rupture in Preeclampsia and HELLP Syndrome: A Catastrophic Presentation. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, C.; Planchamp, F.; Aytulu, T.; Chiva, L.; Cina, A.; Ergönül, Ö.; Fagotti, A.; Haidopoulos, D.; Hasenburg, A.; Hughes, C.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Peri-Operative Management of Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients Undergoing Debulking Surgery. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, S.; Selçuk, I.; Yordanov, A.; Kornovski, Y.; Yalçın, H.; Slavchev, S.; Ivanova, Y.; Dineva, S.; Dzhenkov, D.; Watrowski, R. Paraaortic Lymphadenectomy in Gynecologic Oncology-Significance of Vessels Variations. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, S.; Kornovski, Y.; Slavchev, S.; Ivanova, Y.; Dzhenkov, D.; Dimitrov, N.; Yordanov, A. Pelvic lymphadenectomy in gynecologic oncology—Significance of anatomical variations. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrowski, R. Pregnancy-Preserving Laparoscopic Treatment of Acute Hemoperitoneum Following Lutein Cyst Rupture in Early Gestation. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol 2019, 223, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunwar, S.; Khan, T.; Srivastava, K. Abdominal Pregnancy: Methods of Hemorrhage Control. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2015, 4, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhami, O.; Allen, L.; Flores Mendoza, H.; Murphy, M.A.; Hobson, S.R. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Non-Oncologic Challenge for Gynecologic Oncologists. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, L.; Saini, A.; Quencer, K.; Altun, I.; Albadawi, H.; Khurana, A.; Naidu, S.; Patel, I.; Alzubaidi, S.; Oklu, R. Emerging Approaches to Pre-Hospital Hemorrhage Control: A Narrative Review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancarelli, A.; Birrer, K.L.; Alban, R.F.; Hobbs, B.P.; Liu-DeRyke, X. Hypocalcemia in Trauma Patients Receiving Massive Transfusion. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 202, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, R.K.; Clifford, S.P.; Baker, J.A.; Lenhardt, R.; Haq, M.Z.; Huang, J.; Farah, I.; Businger, J.R. Traumatic Hemorrhage and Chain of Survival. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2023, 31, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potestio, C.P.; Van Helmond, N.; Azzam, N.; Mitrev, L.V.; Patel, A.; Ben-Jacob, T. The Incidence, Degree, and Timing of Hypocalcemia from Massive Transfusion: A Retrospective Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e22093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, D.; Yoshida, Y.; Kushimoto, S. Permissive Hypotension/Hypotensive Resuscitation and Restricted/Controlled Resuscitation in Patients with Severe Trauma. J. Intensive Care 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butwick, A.J.; Goodnough, L.T. Transfusion and Coagulation Management in Major Obstetric Hemorrhage. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2015, 28, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokinen, S.; Kuitunen, A.; Uotila, J.; Yli-Hankala, A. Thromboelastometry-Guided Treatment Algorithm in Postpartum Haemorrhage: A Randomised, Controlled Pilot Trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 130, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, L.; Capelli, P.C.; Carvalho, G.; Ghosh, D.; Ofosu, W.; Seelandt, C.; Trivedi, S. Narrative Review of Open Abdomen Management and Comparison of Different Temporary Abdominal Closure Techniques. J. Abdom. Wall Surg. 2025, 4, 14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Roberts, D.J.; De Waele, J.; Jaeschke, R.; Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; De Keulenaer, B.; Duchesne, J.; Bjorck, M.; Leppaniemi, A.; Ejike, J.C.; et al. Intra-Abdominal Hypertension and the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome: Updated Consensus Definitions and Clinical Practice Guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 1190–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R.; Kirkpatrick, A.W. Intra-Abdominal Pressure, Intra-Abdominal Hypertension, and Pregnancy: A Review. Ann. Intensive Care 2012, 2 (Suppl. 1), S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanaike, S.; Pham, T.; Shalhub, S.; Warner, K.; Hennessy, L.; Moore, E.E.; Maier, R.V.; O’Keefe, G.E.; Cuschieri, J. Effect of immediate enteral feeding on trauma patients with an open abdomen: Protection from nosocomial infections. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2008, 207, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, F.; Roberts, D.; Ansaloni, L.; Ivatury, R.; Gamberini, E.; Kluger, Y.; Moore, E.E.; Coimbra, R.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Pereira, B.M.; et al. The Open Abdomen in Trauma and Non-Trauma Patients: WSES Guidelines. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2018, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.M.; MacGoey, P.; Navarro, A.P.; Brooks, A.J. Damage Control Surgery in the Era of Damage Control Resuscitation. Br. J. Anaesth. 2014, 113, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizobata, Y. Damage Control Resuscitation: A Practical Approach for Severely Hemorrhagic Patients and Its Effects on Trauma Surgery. J. Intensive Care 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, M.J.; Goyal, V.; Levin, D.; Walden, R.L.; Osmundson, S.S.; Pacheco, L.D.; Malbrain, M.L.N.G. Management of Peripartum Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burch, J.M.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, F.A.; Franciose, R. The Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 1996, 76, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, F.; Bruyere, M.; Senat, M.-V.; Purenne, E.; Benhamou, D.; Fernandez, H. Are Standard Intra-Abdominal Pressure Values Different during Pregnancy? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staelens, A.S.E.; Van Cauwelaert, S.; Tomsin, K.; Mesens, T.; Malbrain, M.L.N.; Gyselaers, W. Intra-Abdominal Pressure Measurements in Term Pregnancy and Postpartum: An Observational Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatroux, L.R.; Einarsson, J.I. Keep Your Attention Closer to the Ureters: Ureterolysis in Deep Endometriosis Surgery. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 95, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansbridge, M.M.; Latif, E.R.; Lamdark, L.T.; Wullschleger, M. Renal pelvicalyceal rupture secondary to extraperitoneal pelvic packing (EPP) in the unstable trauma patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr-2018-224910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selloua, M.; Del, M.; Ségal, J.; Chollet, C.; Martinez, A. Acute Limb Ischemia Due to a Common Iliac Artery Thrombosis Following Total Pelvic Exenteration with Pelvic Sidewall Resection: A Case Report. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 59, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolitsas, A.; Williams, E.C.; Lewis, M.R.; Benjamin, E.R.; Demetriades, D. Preperitoneal Pelvic Packing in Isolated Severe Pelvic Fractures Is Associated with Higher Mortality and Venous Thromboembolism: A Matched-Cohort Study. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 236, 115828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Tomar, D.S. Ischemic Gut in Critically Ill (Mesenteric Ischemia and Nonocclusive Mesenteric Ischemia). Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, S157–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heelan, A.A.; Freedberg, M.; Moore, E.E.; Platnick, B.K.; Pieracci, F.M.; Cohen, M.J.; Lawless, R.; Campion, E.M.; Coleman, J.J.; Hoehn, M.; et al. Worth Looking! Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Who Undergo Preperitoneal Pelvic Packing Warrants Screening Duplex. Am. J. Surg. 2020, 220, 1395–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongkind, V.; Earnshaw, J.J.; Bastos Gonçalves, F.; Cochennec, F.; Debus, E.S.; Hinchliffe, R.; Menyhei, G.; Svetlikov, A.V.; Tshomba, Y.; Van Den Berg, J.C.; et al. Editor’s Choice–Update of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Acute Limb Ischaemia in Light of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Based on a Scoping Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 63, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, N.; Crutchfield, M.; LaChant, M.; Ross, S.E.; Seamon, M.J. Early Abdominal Closure Improves Long-Term Outcomes after Damage-Control Laparotomy. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 75, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, M.; Bochicchio, G.; Bochicchio, K.; Ilahi, O.; Rodriguez, E.; Henry, S.; Joshi, M.; Scalea, T. Long-Term Impact of Damage Control Laparotomy: A Prospective Study. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, A.; Jedig, A.; Manekeller, S.; Willms, A.; Pantelis, D.; Matthaei, H.; Schäfer, N.; Kalff, J.C.; von Websky, M.W. Long Term Outcome After Open Abdomen Treatment: Function and Quality of Life. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 590245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righy, C.; Rosa, R.G.; da Silva, R.T.A.; Kochhann, R.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Robinson, C.C.; Teche, S.P.; Teixeira, C.; Bozza, F.A.; Falavigna, M. Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Adult Critical Care Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawardane, I.A.; Jayasundara, D.M.C.S.; Weliange, S.D.S.; Jayasingha, T.D.K.M.; Madugalle, T.M.S.S.B.; Nishshanka, N.M.C.L. Long-Term Morbidity of Peripartum Hysterectomy: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 170, 988–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, S.; Kornovski, Y.; Watrowski, R.; Slavchev, S.; Ivanova, Y.; Yordanov, A. Surgical and Anatomical Basics of Pelvic Debulking Surgery for Advanced Ovarian Cancer–the “Hudson Procedure” as a Cornerstone of Complete Cytoreduction. Chirurgia 2023, 118, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostov, S.; Selçuk, I.; Watrowski, R.; Dineva, S.; Kornovski, Y.; Slavchev, S.; Ivanova, Y.; Yordanov, A. Neglected Anatomical Areas in Ovarian Cancer: Significance for Optimal Debulking Surgery. Cancers 2024, 16, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, I.; Brenner, A.; Shakur-Still, H. Tranexamic Acid for Bleeding: Much More than a Treatment for Postpartum Hemorrhage. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surbek, D.; Vial, Y.; Girard, T.; Breymann, C.; Bencaiova, G.A.; Baud, D.; Hornung, R.; Taleghani, B.M.; Hösli, I. Patient Blood Management (PBM) in Pregnancy and Childbirth: Literature Review and Expert Opinion. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, P.; Schlesinger, T.; Hottenrott, S.; Papsdorf, M.; Wöckel, A.; Sitter, M.; Skazel, T.; Wurmb, T.; Türkmeneli, I.; Härtel, C.; et al. Postpartum hemorrhage: Interdisciplinary consideration in the context of patient blood management. Anaesthesist 2022, 71, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Bendix, J.; Hougaard, K.; Christensen, E.F. Retroperitoneal Packing as Part of Damage Control Surgery in a Danish Trauma Centre—Fast, Effective, and Cost-Effective. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2008, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.A. Artificial Intelligence in Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery Education: Applications, Ethics, and Future Perspectives. JAAOS Glob. Res. Rev. 2025, 9, e25.00174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurello, P.; Pace, M.; Goglia, M.; Pavone, M.; Petrucciani, N.; Carrano, F.M.; Cicolani, A.; Chiarini, L.; Silecchia, G.; D’Andrea, V. Enhancing Surgical Education Through Artificial Intelligence in the Era of Digital Surgery. Am. Surg. 2025, 91, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrowski, R.; Sparić, R. Editorial: Changing Backgrounds and Groundbreaking Changes: Gynecological Surgery in the Third Decade of the 21st Century Volume II. Front. Surg. 2025, 12, 1587048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavone, M.; Goglia, M.; Rosati, A.; Innocenzi, C.; Bizzarri, N.; Seeliger, B.; Mascagni, P.; Ferrari, F.A.; Forgione, A.; Testa, A.C.; et al. Unveiling the Real Benefits of Robot-Assisted Surgery in Gynaecology: From Telesurgery to Image-Guided Surgery and Artificial Intelligence. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2025, 17, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascagni, P.; Alapatt, D.; Sestini, L.; Yu, T.; Alfieri, S.; Morales-Conde, S.; Padoy, N.; Perretta, S. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: Clinical, Technical, and Governance Considerations. Cir. Esp. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 102 (Suppl. 1), S66–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Complication | Mechanism/Incidence |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal | Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) | Elevated IAP from over-packing, edema, or fluid overload; 10–40% in open-abdomen/ DCS cohorts (lower in OB/GYN) |

| Lateral fascial retraction | Prolonged open abdomen → abdominal wall retracts and bowel swells (“loss of domain”); complicates delayed closure | |

| Entero-atmospheric fistula | Exposed bowel + inflammation/infection; rare in OB/GYN | |

| Fascial dehiscence/evisceration | Edema, infection, poor tissue quality; up to ~10% in open-abdomen series | |

| Urological | Ureteral/bladder compression | Packs/hematoma/edema compress urinary tract; often evident 24–48 h post-op |

| Obstructive acute kidney injury | Ureteric kinking/obstruction; bladder outlet compression (esp. with extraperitoneal packing) | |

| Collecting system rupture (rare) | High back-pressure with extraperitoneal pelvic packing | |

| Vascular | Great-vessel compression (IVC/iliac venous outflow) | Excessive or malpositioned packs → ↓ venous return |

| Arterial/venous thrombosis | Vessel injury/ligation + compression; low flow/hypercoagulability | |

| Rebleeding after pack removal | Incomplete control or arterial source; 5–10% (series-dependent) | |

| Neurological | Peripheral neuropathy (sciatic/femoral/obturator) | Compression, over-packing, prolonged positioning |

| Gastrointestinal | Mechanical bowel obstruction | Adhesions or extrinsic compression by packs |

| Paralytic ileus | Inflammation, opioids, electrolyte disturbance | |

| Pelvic floor related | Rectovaginal fistula (rare) | Tissue ischemia/infection in scarred fields |

| Vaginal cuff dehiscence (post-hysterectomy) | Poor tissue quality, infection, tension | |

| Pelvic floor dysfunction | Nerve/muscle injury, scarring | |

| Infectious | Intra-abdominal abscess | Up to 25% in trauma open-abdomen series; lower in OB/GYN with early pack removal |

| Sepsis | Secondary to ongoing contamination/necrosis | |

| Surgical-site infection | Higher with immunosuppression, transfusion, prolonged open abdomen | |

| Systemic | Pyrexia (post-op) | Inflammatory response; infection must be excluded |

| DVT/PE | Immobility, venous injury, hypercoagulability | |

| Multi-organ failure | Ongoing shock/“lethal triad” |

| Complication | Typical Early Signs | Prevention | Diagnosis/ Monitoring | Management Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent bleeding/persistent hemorrhage | Ongoing drain output, instability, Hb drop | Early correction of coagulopathy (MTP, fibrinogen/platelets); adequate pad number/depth; avoid tight circumferential wraps | Hemodynamics, Hb/INR/fibrinogen; bedside US/CT if stable | Return to OR for re-packing or targeted hemostasis; correct coagulopathy; consider IR adjuncts (e.g., uterine/internal iliac embolization or temporary balloon occlusion) for a focal arterial source |

| Bleeding on pack removal | Brisk oozing at re-look | Planned re-look within recommended dwell time; normothermia and corrected labs before removal | Intra-op assessment during re-look | Remove packs sequentially with direct visualization; add hemostats/ligations; re-pack if needed; consider IR embolization for focal bleeding |

| Infection/intra-abdominal abscess | Fever, leukocytosis, foul drains | Early pack removal (see footnote); sterile technique; minimize devitalized tissue | WBC, CRP; imaging (US/CT) if stable | Culture-directed antibiotics; drain collections (percutaneous if feasible); debridement at re-look if source persists |

| Surgical-site infection/wound dehiscence | Erythema, discharge, fascial gaping | NPWT/appropriate TAC; avoid excessive moisture; glycemic control | Bedside exam; TAC checks | Open and drain; debride nonviable tissue; optimize TAC; staged closure once clean |

| Intra-abdominal hypertension/ACS | Rising ventilator pressures, oliguria, tense abdomen | Limit over-packing; avoid tight circumferential pressure; judicious fluids | Measure IAP (bladder); monitor UO and ventilator pressures | Decompress (release tension/adjust packs, reopen TAC); correct drivers (fluid balance); manage per obstetric ACS guardrails |

| Visceral injury (bowel/mesentery) | Unexpected hemoperitoneum, enteric leakage, peritonitis | Protect viscera with sheets; place pads deep → superficial; avoid shearing | Intra-op inspection at re-look; CT with contrast if stable | Repair primarily if feasible; resection/diversion for non-viable or contaminated injuries; broad-spectrum antibiotics |

| Enteric fistula (entero-/enterocutaneous) | Persistent enteric drainage, skin irritation | Gentle packing; early re-look; avoid pad edges abrading serosa | Drain amylase/bile; CT with oral contrast if stable | Sepsis control, skin protection, nutritional support (consider TPN); diversion/stoma if needed; delayed reconstruction |

| Ureteral obstruction/hydronephrosis | Rising creatinine, flank pain (later), low UO | Know ureteral course; avoid medializing pads against ureter | US (hydronephrosis); CT if stable | Reduce/reposition packs; ureteral stent or percutaneous nephrostomy if obstruction persists |

| Bladder compression/retention or injury | Low UO despite resuscitation, suprapubic distension, hematuria | Avoid pad pressure on bladder dome; ensure Foley patency | Bladder scan/flush; cystography if injury suspected | Reposition packs; ensure Foley function; repair injury at re-look if confirmed |

| Vascular thrombosis/VTE | Calf swelling, hypoxia | Early mechanical prophylaxis; start pharmacologic prophylaxis once hemostasis secure | D-dimer (limited), duplex/CTPA if clinically indicated | Anticoagulate when safe; IVC filter selectively if anticoagulation contraindicated |

| Renal impairment (pre-renal/obstructive) | Rising creatinine, oliguria | Goal-directed resuscitation; avoid over-packing near ureters | UO/hour, creatinine; renal US | Optimize volume/pressors; correct ACS/obstruction; renal consult if persistent |

| Respiratory compromise from packing | Elevated airway pressures, low tidal volumes | Avoid diaphragm-elevating pressure; limit over-packing | Ventilator pressures, ABGs | Lighten/reposition packs; adjust ventilator; treat ACS if present |

| Retained pack/count discrepancy | Pack count off; radio-opaque marker seen | Strict count and documentation; radio-opaque pads only | Intra-op X-ray if count mismatch | Immediate search; return to OR if not found |

| Loss of abdominal domain / difficult fascial closure | Progressive fascial retraction | Early plan for closure; NPWT with progressive tension; avoid prolonged dwell | Bedside fascial gap assessment | Progressive closure techniques; later component separation if needed; plastic-surgery consult |

| Empty pelvis syndrome | Small bowel descent into pelvic dead space → adhesions/obstruction | Omentoplasty or pelvic exclusion techniques when large pelvic dead space anticipated | Clinical signs of obstruction; imaging if stable | Omentoplasty; consider pelvic mesh/sling solutions in selected cases; early recognition and surgical correction if obstructive course |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostov, S.; Kornovski, Y.; Yordanov, A.; Slavchev, S.; Ivanova, Y.; Alkatout, I.; Watrowski, R. Damage Control Surgery in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Abdomino-Pelvic Packing in Multimodal Hemorrhage Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207207

Kostov S, Kornovski Y, Yordanov A, Slavchev S, Ivanova Y, Alkatout I, Watrowski R. Damage Control Surgery in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Abdomino-Pelvic Packing in Multimodal Hemorrhage Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207207

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostov, Stoyan, Yavor Kornovski, Angel Yordanov, Stanislav Slavchev, Yonka Ivanova, Ibrahim Alkatout, and Rafał Watrowski. 2025. "Damage Control Surgery in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Abdomino-Pelvic Packing in Multimodal Hemorrhage Management" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207207

APA StyleKostov, S., Kornovski, Y., Yordanov, A., Slavchev, S., Ivanova, Y., Alkatout, I., & Watrowski, R. (2025). Damage Control Surgery in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Abdomino-Pelvic Packing in Multimodal Hemorrhage Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207207