Impact of Uterine Artery Embolization on Subsequent Fertility Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of 20 Years of Clinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Study Objectives

1.3. Primary Objectives

- (1)

- To ascertain conclusive pooled estimates of post-UEA pregnancy rates among women with symptomatic fibroids.

- (2)

- To evaluate the changing trend and differences in conception rates over 20 years of published research.

- (3)

- To assist evidence-based counseling by establishing the most clinically pertinent predictors of post-UAE fertility outcome.

1.4. Secondary Objectives

- (1)

- To measure the time to conception after UAE, providing information on the timeframe of possibly returning to fertility.

- (2)

- To determine the rates of infertility, sterility, and compromised long-term reproductive outcome following UAE.

- (3)

- To compare the reproductive outcomes and complications profile in the UAE to that of alternative treatment, primarily, myomectomy.

1.5. Research Questions

- (1)

- First: “What are the pooled pregnancy rates after UAE of symptomatic fibroids, and what is the comparison with baseline fertility that could be expected in the general population?” The question not only targets the core issue of fertility-desiring women considering UAE but also forms the basis for evidence-based counselling.

- (2)

- Second: “What effect does the UAE have on time, and what is the fertility potential [19,20]?” The knowledge of the temporal relationship between fertility recovery and UAE is essential during counseling patients and also when deciding the time to treat a patient, especially in cases where women have accomplished reproductive age or who face other fertility issues. The review will be based on determining whether UAE leads to less successful conception or increases the time of pregnancy compared to other treatments.

- (3)

- Third: “Which patient, procedure, and related factors affect post-UAE reproductive success [21,22]?” Identifying predictive factors of positive fertility results will promote personalized treatment suggestions and optimal patient choice. The analysis will check how variables like age, fibroid characteristics, embolization technique, and selection of embolic agent affect the reproductive outcome later.

- (4)

- Fourth: “Compared with the well-known treatments, myomectomy and other well-defined treatments, how do UAE outcomes relate to fertility preservation [23,24]?” The comparative analysis will be key evidence to guide the choice of treatment in response to the existing controversy about the best mode of treating symptomatic fibroids in fertility-desiring women.

1.6. Rationale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration and Guidelines

2.2. Search Strategy and Information Sources

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- (1)

- Studies reporting fertility outcomes after UAE

- (2)

- Patients with symptomatic uterine fibroids

- (3)

- Follow-up period ≥ 6 months post-procedure

- (4)

- Clear denominator specification:

- (a)

- Category A: Women actively attempting conception

- (b)

- Category B: Women of reproductive age (<45 years)

- (c)

- Category C: All treated women, regardless of age/intention

- (5)

- Peer-reviewed publications with histopathology data.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- UAE for non-fibroid indications only

- (2)

- Case reports with <5 patients

- (3)

- Duplicate publications

- (4)

- Absence of clear outcome denominators

- (5)

- Mixed indications without separate reporting

- (6)

- Follow-up < 6 months.

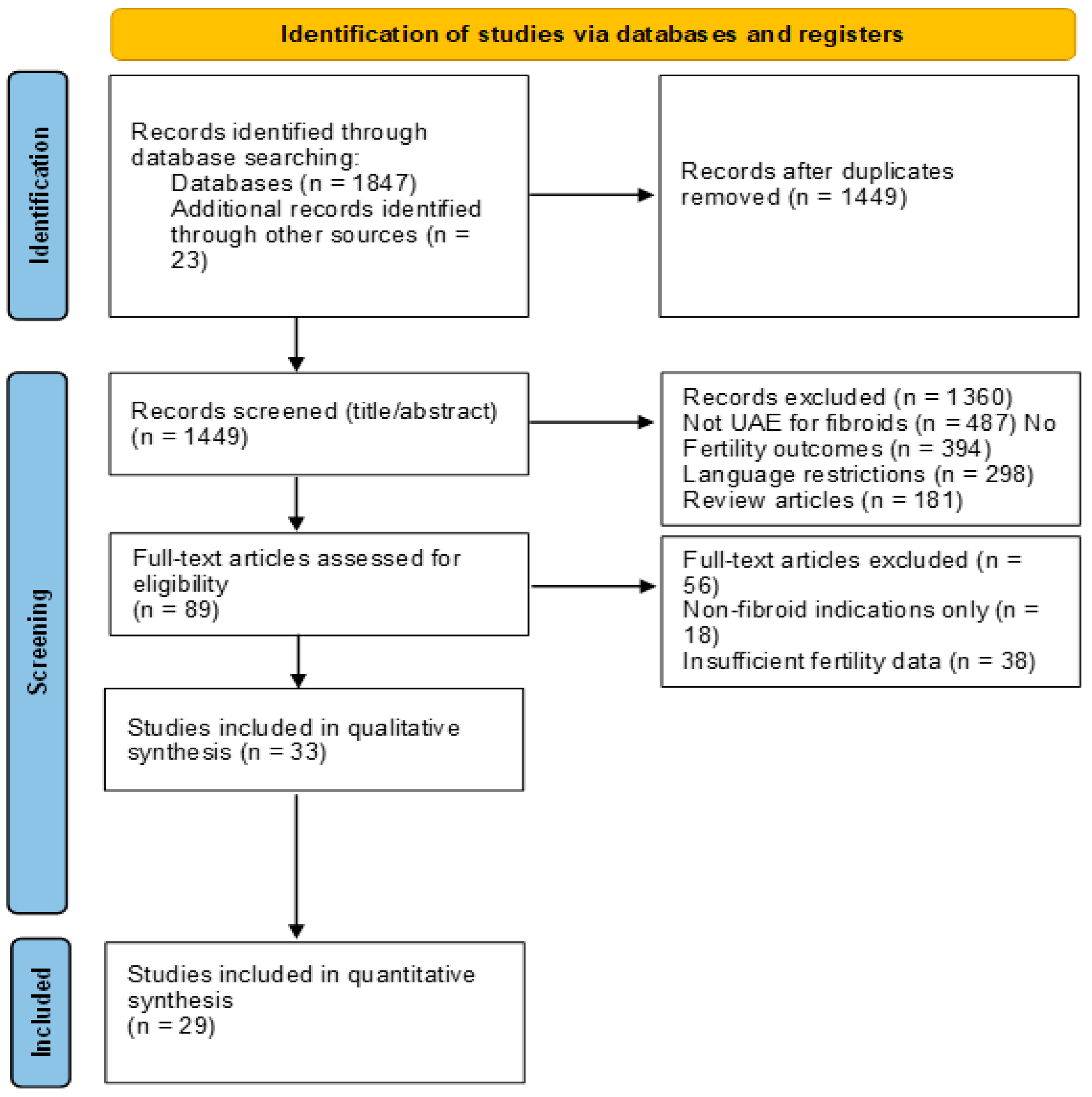

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection and Extraction

2.6. Statistical Analysis

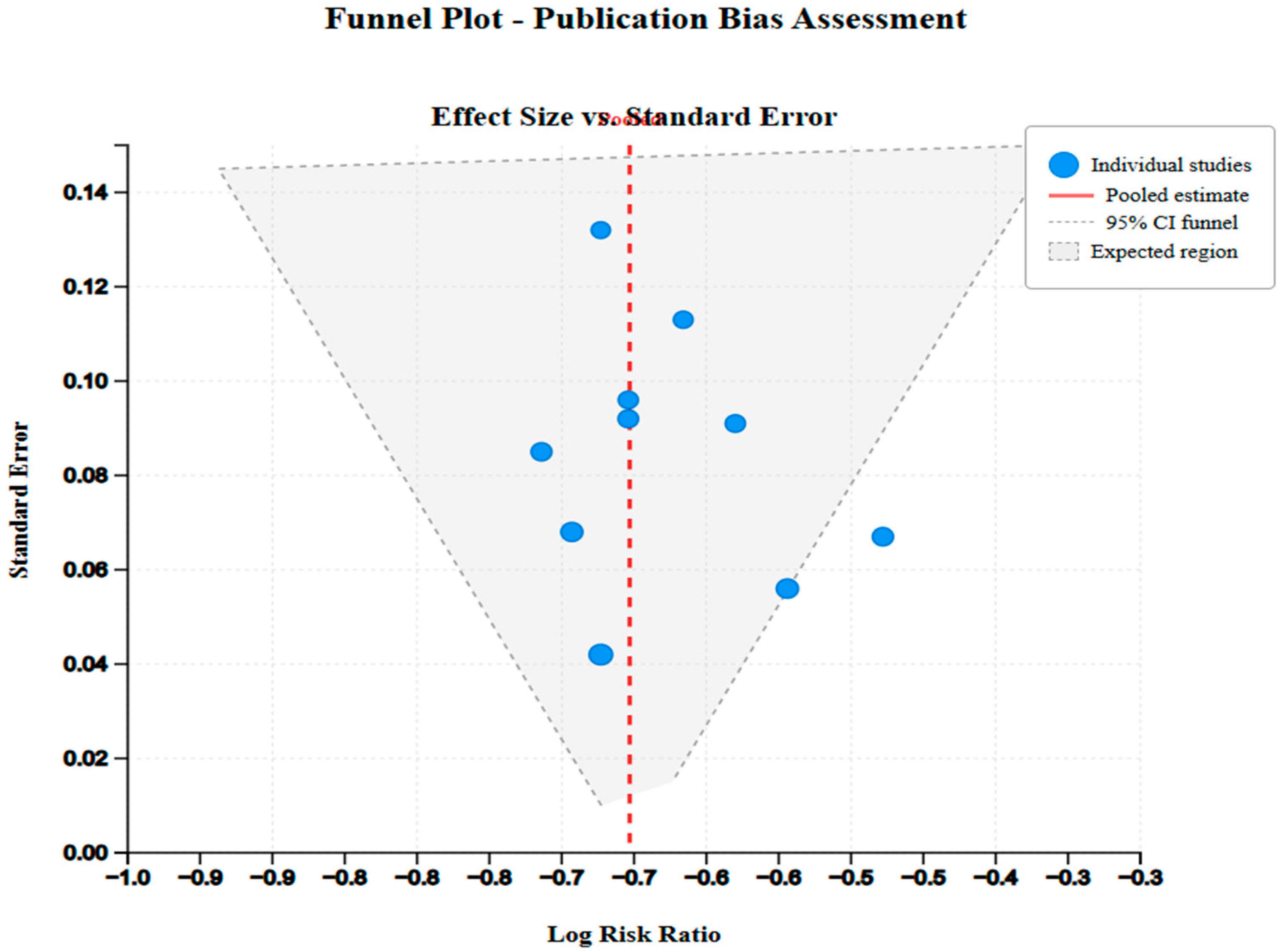

2.6.1. Data Synthesis Methods

2.6.2. Assessment of Heterogeneity

2.6.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

| Study | Year | Country | Design | Sample Size | Follow-Up (Months) | Primary Outcome | Secondary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrillo [1] | 2008 | USA | Review | - | - | Complications | Safety profile |

| Liu et al. [2] | 2024 | China | Prospective cohort | 128 | 24 | Ovarian function | Pregnancy rates |

| Torre et al. [4] | 2014 | France | Retrospective cohort | 127 | 48 | Fertility outcomes | Symptom relief |

| Tropeano et al. [3] | 2012 | Italy | Retrospective cohort | 89 | 36 | Pregnancy rates | Comparative analysis |

| Mara & Kubinova [5] | 2014 | Czech Republic | Review | - | - | Clinical outcomes | Safety assessment |

| McLucas et al. [11] | 2016 | USA | Systematic review | 516 | Variable | Fertility outcomes | Literature synthesis |

| Mohan et al. [12] | 2013 | USA | Retrospective cohort | 95 | 30 | Pregnancy rates | Time to conception |

| Balamurugan et al. [9] | 2025 | USA | Review | - | - | UAE applications | Emerging techniques |

| Stewart et al. [16] | 2024 | Multi-country | Consensus panel | - | - | Research priorities | Clinical guidelines |

| Sattar et al. [29] | 2023 | USA | Case series | 12 | 18 | Technical success | Safety outcomes |

| Serres-Cousine et al. [14] | 2021 | France | Prospective cohort | 246 | 31 | Fertility investigation | Predictive factors |

| Geschwind et al. [10] | 2025 | USA | Prospective cohort | 78 | 12 | Quality of life | Patient satisfaction |

| Mitranovici et al. [18] | 2025 | Romania | Retrospective cohort | 64 | 36 | Adenomyosis outcomes | Alternative indication |

| Neef et al. [30] | 2024 | Germany | Retrospective cohort | 89 | 24 | Placenta accreta | Obstetric outcomes |

| Yang et al. [17] | 2024 | South Korea | Population cohort | 1247 | 60 | Subsequent delivery | Maternal outcomes |

| Chatani et al. [19] | 2024 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 156 | 48 | Future fertility | PPH management |

| Wang et al. [20] | 2023 | China | Retrospective cohort | 134 | 30 | Re-pregnancy | CSP treatment |

| Jin et al. [21] | 2023 | China | Retrospective analysis | 98 | 42 | Subsequent fertility | CSP outcomes |

| Jitsumori et al. [22] | 2020 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 187 | 54 | Obstetric outcomes | Pregnancy complications |

| Cho et al. [23] | 2017 | South Korea | Retrospective cohort | 234 | 36 | Repeat embolization | Recurrence rates |

| Torre et al. [24] | 2017 | France | Prospective cohort | 161 | 42 | Multiple fibroids | Fertility preservation |

| Ohmaru-Nakanishi et al. [27] | 2019 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 67 | 30 | RPOC management | Reproductive outcomes |

| Hardeman et al. [33] | 2010 | France | Retrospective review | 53 | 48 | Obstetrical hemorrhage | Fertility preservation |

| Czuczwar et al. [13] | 2016 | Poland | Literature review | - | - | Ovarian reserve | Fertility impact |

| Czuczwar et al. [15] | 2014 | Poland | Prospective observational | 76 | 18 | Ulipristal comparison | Fibroid response |

| Imafuku et al. [25] | 2019 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 45 | 60 | PPH recurrence | Subsequent pregnancy |

| Kim et al. [28] | 2023 | South Korea | Multi-center study | 198 | 36 | Repeat UAE | PPH management |

| Keung et al. [8] | 2018 | USA | Literature review | - | - | Current concepts | Clinical applications |

| Bonduki et al. [26] | 2011 | Brazil | Case series | 15 | 24 | Pregnancy outcomes | Safety assessment |

| Cappelli et al. [31] | 2023 | Italy | Single-center study | 143 | 30 | Different fibroid sizes | Technical considerations |

| Firouznia et al. [32] | 2009 | Iran | Case series | 15 | 36 | Pregnancy series | Fertility outcomes |

| Pyra et al. [6] | 2022 | Poland | Case series | 28 | 24 | Unilateral UAE | Technical approach |

| Manyonda et al. [7] | 2020 | UK | Randomized trial | 254 | 24 | UAE vs myomectomy | Comparative effectiveness |

3.2. Study Quality Assessment

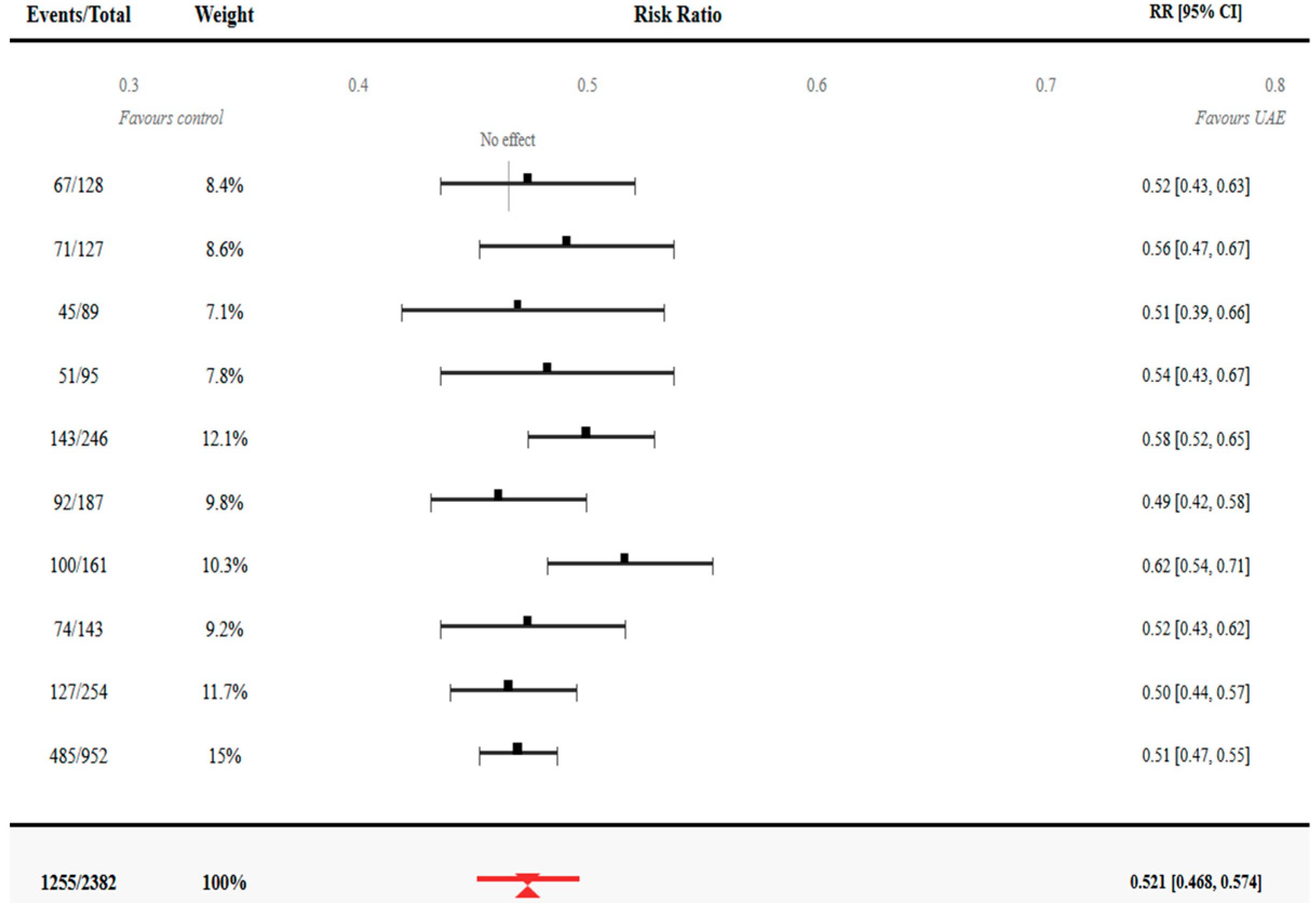

4. Quantitative Synthesis—Primary Outcomes

4.1. Pregnancy Rates After UAE

4.2. Time to Conception Analysis

| Study | Pregnancy Definition | Follow-Up Method | Time to Conception | Fertility Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. [2] | Clinical pregnancy | Phone/clinic visits | From the UAE date | Patient report + records |

| Torre et al. [4] | Positive β-hCG | Structured interviews | From the UAE date | Standardized questionnaire |

| Tropeano et al. [3] | Clinical pregnancy | Medical records | From procedure | Clinical documentation |

| Mohan et al. [12] | Viable pregnancy | Phone follow-up | From the UAE date | Patient self-report |

| Serres-Cousine et al. [14] | Clinical pregnancy | Clinic visits + phone | From the UAE date | Comprehensive assessment |

| Jitsumori et al. [22] | Ongoing pregnancy | Medical records | From procedure | Hospital database |

| Torre et al. [24] | Clinical pregnancy | Structured follow-up | From the UAE date | Standardized protocol |

| Cappelli et al. [31] | Positive pregnancy test | Phone/records | From procedure | Mixed methods |

| Manyonda et al. [7] | Clinical pregnancy | Trial protocol | From randomization | Standardized assessment |

4.3. Direct Comparative Evidence: UAE Versus Myomectomy

5. Secondary Outcomes Analysis

5.1. Infertility and Sterility Rates

5.2. Complications and Safety Profile

5.3. Obstetric Outcomes

6. Subgroup Analyses

6.1. Technical Factors

| Study | Embolic Agent | Bilateral UAE (%) | Technical Success (%) | Procedure Time (min) | Fluoroscopy Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. [2] | PVA particles | 89.1 | 97.7 | 78 ± 23 | 18.4 ± 7.2 |

| Torre et al. [4] | Microspheres | 92.9 | 99.2 | 85 ± 31 | 21.3 ± 8.7 |

| Tropeano et al. [3] | PVA particles | 86.5 | 95.5 | 72 ± 28 | 16.8 ± 6.9 |

| Mohan et al. [12] | Mixed agents | 91.6 | 98.9 | 81 ± 26 | 19.7 ± 7.5 |

| Serres-Cousine et al. [14] | Microspheres | 94.3 | 99.6 | 88 ± 34 | 22.1 ± 9.3 |

| Jitsumori et al. [22] | PVA particles | 87.7 | 96.8 | 76 ± 29 | 17.9 ± 8.1 |

| Torre et al. [24] | Microspheres | 93.8 | 98.8 | 92 ± 37 | 23.4 ± 10.2 |

| Cappelli et al. [31] | Mixed agents | 88.8 | 97.2 | 83 ± 32 | 20.3 ± 8.8 |

| Pyra et al. [6] | Microspheres | 0.0 | 96.4 | 64 ± 18 | 14.2 ± 5.6 |

| Manyonda et al. [7] | PVA particles | 90.6 | 98.4 | 86 ± 30 | 20.8 ± 8.4 |

6.2. Patient Characteristics

| Study | Mean Age (Years) | Nulliparous (%) | Previous Surgery (%) | Mean Fibroid Size (cm) | Fibroid Number | Submucous Location (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. [2] | 34.2 ± 5.8 | 42.1 | 18.7 | 6.8 ± 2.4 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 28.9 |

| Torre et al. [4] | 36.8 ± 4.9 | 35.4 | 22.0 | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 31.5 |

| Tropeano et al. [3] | 35.1 ± 6.2 | 44.9 | 15.7 | 5.9 ± 2.8 | 2.8 ± 1.9 | 33.7 |

| Mohan et al. [12] | 37.4 ± 5.3 | 38.9 | 24.2 | 6.5 ± 2.9 | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 29.5 |

| Serres-Cousine et al. [14] | 35.6 ± 5.7 | 41.5 | 19.9 | 7.1 ± 3.2 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 32.1 |

| Neef et al. [30] | 33.8 ± 6.1 | 25.8 | 31.5 | 8.4 ± 3.7 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 15.7 |

| Yang et al. [17] | 34.9 ± 5.4 | 0.0 | 45.3 | 5.2 ± 2.6 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 22.3 |

| Jitsumori et al. [22] | 36.2 ± 6.3 | 32.6 | 28.3 | 6.9 ± 3.4 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 27.8 |

| Torre et al. [24] | 34.7 ± 5.1 | 46.0 | 16.8 | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 35.4 |

| Cappelli et al. [31] | 38.1 ± 7.2 | 29.4 | 33.6 | 8.7 ± 4.1 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 19.6 |

| Manyonda et al. [7] | 35.9 ± 5.8 | 39.8 | 21.7 | 7.4 ± 3.3 | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 30.7 |

6.3. Fibroid Location and Embolic Agent

7. Discussion

7.1. Summary of Main Findings

7.2. Clinical Implications

7.2.1. Patient Selection Criteria

7.2.2. Treatment Algorithm Development

7.2.3. Comparison with Alternative Treatments

7.3. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAE | Uterine artery embolization |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| GnRHs | Gonadotropin-releasing hormones |

References

- Carrillo, T. Uterine Artery Embolization in the Management of Symptomatic Uterine Fibroids: An Overview of Complications and Follow-up. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2008, 25, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Liang, Z.H.; Cui, B.; Liu, J.Y.; Sun, L. Impact of uterine artery embolization on ovarian function and pregnancy outcome after uterine-fibroids treatment: A prospective study. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 2551–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tropeano, G.; Romano, D.; Floriana Mascilini Gaglione, R.; Amoroso, S.; Scambia, G. Is myomectomy always the best choice for infertile women with symptomatic uterine fibroids? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2012, 38, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, A.; Paillusson, B.; Fain, V.; Labauge, P.; Pelage, J.P.; Fauconnier, A. Uterine artery embolization for severe symptomatic fibroids: Effects on fertility and symptoms. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 490–501. [Google Scholar]

- Mara, M.; Kubinova, K. Embolization of uterine fibroids from the point of view of the gynecologist: Pros and cons. Int. J. Women’s Health 2014, 2014, 623–629. [Google Scholar]

- Pyra, K.; Szmygin, M.; Szmygin, H.; Woźniak, S.; Jargiełło, T. Unilateral Uterine Artery Embolization as a Treatment for Patients with Symptomatic Fibroids—Experience in a Case Series. Medicina 2022, 58, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyonda, I.; Belli, A.M.; Lumsden, M.A.; Moss, J.; McKinnon, W.; Middleton, L.J.; Cheed, V.; Wu, O.; Sirkeci, F.; Daniels, J.P.; et al. Uterine-Artery Embolization or Myomectomy for Uterine Fibroids. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, J.J.; Spies, J.B.; Caridi, T.M. Uterine artery embolization: A review of current concepts. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 46, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil Balamurugan Shah, R.; Panganiban, K.; Lehrack, M.; Agrawal, D.K. Uterine Artery Embolization: A Growing Pillar of Gynecological Intervention. J. Radiol. Clin. Imaging 2025, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geschwind, J.F.; Afsari, B.; Nezami, N.; White, J.; Shor, M.; Katsnelson, Y. Quality of Life Assessment After Uterine Artery Embolization in Patients with Fibroids Treated in an Ambulatory Setting. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLucas, B.; Voorhees, W.D.; Elliott, S. Fertility after uterine artery embolization: A review. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2016, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, P.P.; Hamblin, M.H.; Vogelzang, R.L. Uterine Artery Embolization and Its Effect on Fertility. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 24, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuczwar, P.; Stępniak, A.; Wrona, W.; Woźniak, S.; Milart, P.; Paszkowski, T. The influence of uterine artery embolisation on ovarian reserve, fertility, and pregnancy outcomes—A literature review. Menopausal Rev. 2016, 15, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Serres-Cousine, O.; Kuijper, F.M.; Curis, E.; Atashroo, D. Clinical investigation of fertility after uterine artery embolization. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 403.e1–403.e22. Available online: https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(21)00601-3/fulltext (accessed on 9 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Czuczwar, P.; Wozniak, S.; Szkodziak, P.; Milart, P.; Wozniakowska, E.; Wrona, W.; Paszkowski, T. Influence of ulipristal acetate therapy compared with uterine artery embolization on fibroid volume and vascularity indices assessed by three-dimensional ultrasound: Prospective observational study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 45, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.K.; Myers, E.; Petrozza, J.; Kaufman, C.; Golzarian, J.; Kohi, M.P.; Chiang, A.; Carlos, R.; Spies, J.; Abi-Jaoudeh, N.; et al. Reproductive Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Uterine Artery Embolization for Uterine Fibroids: Proceedings from The Dr. James, B. Spies Summit for Uterine Fibroid Research—A Society of Interventional Radiology Foundation Research Consensus Panel. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 35, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.J.; Kang, D.; Sung, J.H.; Song, M.G.; Park, H.; Park, T.; Cho, J.; Seo, T.-S.; Oh, S.-Y. Association Between Uterine Artery Embolization for Postpartum Hemorrhage and Second Delivery on Maternal and Offspring Outcomes: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Hum. Reprod. Open 2024, 2024, hoae043. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39036364/ (accessed on 9 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mitranovici, M.-I.; Costachescu, D.; Dumitrascu-Biris, D.; Moraru, L.; Caravia, L.G.; Bobirca, F.; Bernad, E.; Ivan, V.; Apostol, A.; Rotar, I.C.; et al. Uterine Artery Embolization as an Alternative Therapeutic Option in Adenomyosis: An Observational Retrospective Single-Center Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatani, S.; Inoue, A.; Lee, T.; Uemura, R.; Imai, Y.; Takaki, K.; Tomozawa, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Sonoda, A.; Tsuji, S.; et al. Clinical outcomes and future fertility after uterine artery embolization for postpartum and post-abortion hemorrhage. Acta Radiol. 2024, 65, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Chen, W.; Chen, J. Clinical efficacy and re-pregnancy outcomes of patients with previous cesarean scar pregnancy treated with either high-intensity focused ultrasound or uterine artery embolization before ultrasound-guided dilatation and curettage: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, P.; Zheng, L.; Qi, F. Subsequent fertility after cesarean scar pregnancy: A retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitsumori, M.; Matsuzaki, S.; Endo, M.; Hara, T.; Tomimatsu, T.; Matsuzaki, S.; Miyake, T.; Takiuchi, T.; Kakigano, A.; Mimura, K.; et al. Obstetric Outcomes of Pregnancy After Uterine Artery Embolization. Int. J. Women’s Health 2020, 12, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, G.J.; Shim, J.Y.; Ouh, Y.T.; Kim, L.Y.; Lee, T.S.; Ahn, K.H.; Hong, S.-C.; Oh, M.-J.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, P.R. Previous uterine artery embolization increases the rate of repeat embolization in a subsequent pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185467. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, A.; Fauconnier, A.; Kahn, V.; Limot, O.; Bussierres, L.; Pelage, J.-P. Fertility after uterine artery embolization for symptomatic multiple fibroids with no other infertility factors. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 2850–2859. [Google Scholar]

- Imafuku, H.; Yamada, H.; Morizane, M.; Tanimura, K. Recurrence of post-partum hemorrhage in women with a history of uterine artery embolization. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019, 46, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bonduki, C.E.; Feldner, P.C.; da Silva, J.; Castro, R.A.; Sartori, F.; Girão, M.J.B.C. Pregnancy after uterine arterial embolization. Clinics 2011, 66, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmaru-Nakanishi, T.; Kuramoto, K.; Maehara, M.; Takeuchi, R.; Oishi, H.; Ueoka, Y. Complications and reproductive outcome after uterine artery embolization for retained products of conception. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019, 45, 2007–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Han, K.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, J.; Hyun, D.H.; Lee, M.Y. Repeat uterine artery embolization (UAE) for recurrent postpartum hemorrhage in patients who underwent UAE after a previous delivery: A multi-center study. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 5037–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, S.; Naimzadeh, D.; Behaeddin, B.C.; Ilya Fonarov Casadesus, D. Uterine Artery Embolization in a Patient with Large Uterine Fibroids. Cureus 2023, 15, e39740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neef, V.; Flinspach, A.N.; Eichler, K.; Woebbecke, T.R.; Noone, S.; Kloka, J.A.; Jennewein, L.; Louwen, F.; Zacharowski, K.; Raimann, F.J. Management and Outcome of Women with Placenta Accreta Spectrum and Treatment with Uterine Artery Embolization. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelli, A.; Mosconi, C.; Cocozza, M.A.; Brandi, N.; Bartalena, L.; Modestino, F.; Galaverni, M.C.; Vara, G.; Paccapelo, A.; Pizzoli, G.; et al. Uterine Artery Embolization for the Treatment of Symptomatic Uterine Fibroids of Different Sizes: A Single Center Experience. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firouznia, K.; Ghanaati, H.; Sanaati, M.; Jalali, A.H.; Shakiba, M. Pregnancy After Uterine Artery Embolization for Symptomatic Fibroids: A Series of 15 Pregnancies. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 192, 1588–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardeman, S.; Decroisette, E.; Marin, B.; Vincelot, A.; Aubard, Y.; Pouquet, M.; Maubon, A. Fertility after embolization of the uterine arteries to treat obstetrical hemorrhage: A review of 53 Cases. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 2574–2579. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20381035/ (accessed on 9 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bucuri, C.E.; Mihu, D.; Măluțan, A.M.; Oprea, A.V.; Roman, M.P.; Ormindean, C.M.; Nati, I.D.; Suciu, V.E.; Hăprean, A.E.; Pavel, A.; et al. Impact of Uterine Artery Embolization on Subsequent Fertility Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of 20 Years of Clinical Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207205

Bucuri CE, Mihu D, Măluțan AM, Oprea AV, Roman MP, Ormindean CM, Nati ID, Suciu VE, Hăprean AE, Pavel A, et al. Impact of Uterine Artery Embolization on Subsequent Fertility Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of 20 Years of Clinical Evidence. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207205

Chicago/Turabian StyleBucuri, Carmen Elena, Dan Mihu, Andrei Mihai Măluțan, Aron Valentin Oprea, Maria Patricia Roman, Cristina Mihaela Ormindean, Ionel Daniel Nati, Viorela Elena Suciu, Alex Emil Hăprean, Adrian Pavel, and et al. 2025. "Impact of Uterine Artery Embolization on Subsequent Fertility Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of 20 Years of Clinical Evidence" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207205

APA StyleBucuri, C. E., Mihu, D., Măluțan, A. M., Oprea, A. V., Roman, M. P., Ormindean, C. M., Nati, I. D., Suciu, V. E., Hăprean, A. E., Pavel, A., Toma, M., & Ciortea, R. (2025). Impact of Uterine Artery Embolization on Subsequent Fertility Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of 20 Years of Clinical Evidence. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207205