Renal Cell Carcinoma with Duodenal Metastasis: Is There a Place for Surgery? A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- (1)

- Patient characteristics: age, sex.

- (2)

- Clinical, biological, and radiological presentation: symptoms at diagnosis, biological abnormalities, CT scan results, endoscopic features, and other metastatic sites.

- (3)

- Tumor characteristics: side of the primary renal cancer, synchronous or metachronous presentation, and disease-free interval (defined as the time between resection of the initial tumor and diagnosis of duodenal metastasis).

- (4)

- Treatment and perioperative course: type of surgery performed and reported complications.

- (5)

- Outcome: overall survival.

3. Results

3.1. Data Extraction

3.2. Haracteristics of Patients

3.3. Clinical Presentation

3.4. Complementary Exams

4. Treatment and Outcome

4.1. Treatment Strategy

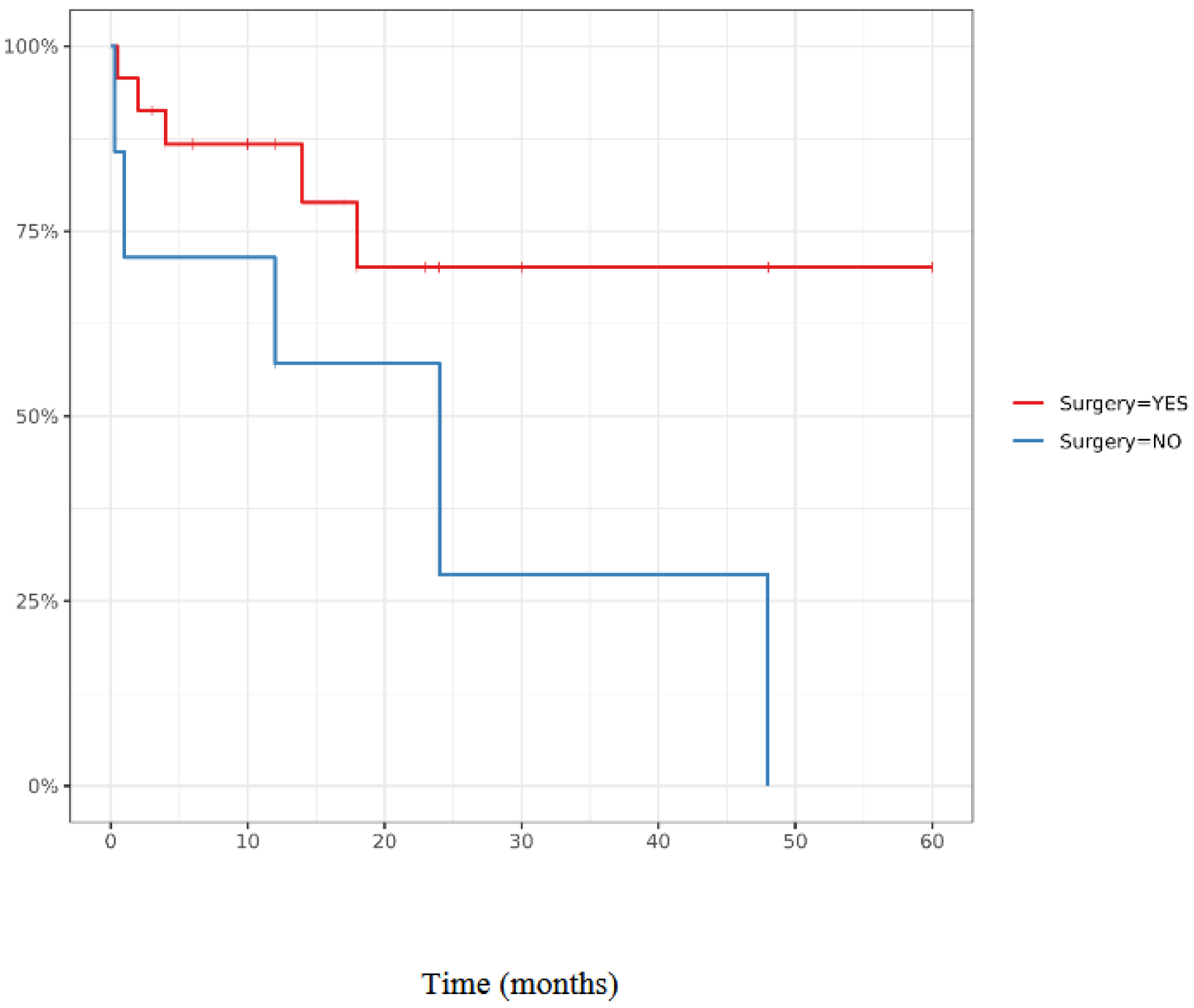

4.2. Surgical Procedure Outcomes and Comparison with Non Surgical Procedure Management

5. Discussion

5.1. Features of Duodenal Metastases

5.2. Role of Metastasectomy in Oligometastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

- -

- Asymptomatic presentation

- -

- No extrahepatic diseases

- -

- Solitary metastasis

- -

- Absence of vascular invasion

- -

- Ability to complete resect tumor

5.3. Duodenal Metastases of RCC: Surgery and Outcome

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ljungberg, B.; Albiges, L.; Abu-Ghanem, Y.; Bensalah, K.; Dabestani, S.; Fernández-Pello, S.; Giles, R.H.; Hofmann, F.; Hora, M.; Kuczyk, M.A.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma: The 2019 Update. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouprêt, M.; Audenet, F.; Roumiguié, M.; Pignot, G.; Masson-Lecomte, A.; Compérat, E.; Houédé, N.; Larré, S.; Brunelle, S.; Xylinas, E.; et al. French ccAFU Guidelines—Update 2020–2022: Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Progres Urol. J. Assoc. Fr. Urol. Soc. Fr. Urol. 2020, 30, S52–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanthan, R.; Gomez, D.; Senger, J.-L.; Kanthan, S.C. Endoscopic biopsies of duodenal polyp/mass lesions: A surgical pathology review. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 63, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamuro, M.; Okada, H.; Matsueda, K.; Inaba, T.; Kusumoto, C.; Imagawa, A.; Yamamoto, K. Metastatic tumors in the duodenum: A report of two cases. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, E.; Hassani, A.; Vaishampayan, U.; Shi, D.; Pontes, J.E.; Weaver, D.W. Surgical excision of duodenal/pancreatic metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.A.; Mendelson, R.M. Duodenal haemorrhage resulting from renal cell carcinoma metastases. Australas. Radiol. 1995, 39, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Chen, J.J.; Changchien, C.S. Endoscopic features of metastatic tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy 1996, 28, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, K.A.; Tsao, J.I.; Rossi, R.L.; Braasch, J.W. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to ampulla of Vater: An unusual lesion amenable to surgical resection. Surgery 1996, 119, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.K.; Hale, J.E. Late presentation of a solitary metastasis of renal cell carcinoma as an obstructive duodenal mass. Postgrad. Med. J. 1996, 72, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, R.M.; Ramj, A.S.; Flint, J.D.; Scudamore, C.H.; Yoshida, E.M. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding from an ampullary tumour in a patient with a remote history of renal cell carcinoma: A diagnostic conundrum. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1998, 12, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavaşçaoğlu, I.; Korun, N.; Oktay, B.; Simşek, U.; Ozyurt, M. Renal cell carcinoma with solitary synchronous pancreaticoduodenal and metachronous periprostatic metastases: Report of a case. Surg. Today 1999, 29, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmura, Y.; Ohta, T.; Doihara, H.; Shimizu, N. Local recurrence of renal cell carcinoma causing massive gastrointestinal bleeding: A report of two patients who underwent surgical resection. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 30, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, M.; Miura, Y.; Matsuda, M.; Watanabe, G. Concomitant duodenal and pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: Report of a case. Surg. Today 2001, 31, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.G.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.T.; Yeon, J.E.; Byun, K.S.; Kim, J.S.; Bak, Y.T.; Lee, C.H. Simultaneous duodenal and colon masses as late presentation of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2002, 17, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loualidi, A.; Spooren, P.F.M.J.; Grubben, M.J.A.L.; Blomjous, C.E.M.; Goey, S.H. Duodenal metastasis: An uncommon cause of occult small intestinal bleeding. Neth. J. Med. 2004, 62, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.-T.; Lee, K.-T.; Chai, C.-Y. Unusual upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to late metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: A case report. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2004, 20, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, A.; Das, A.; Kumar, Y.; Kochhar, R. Renal cell carcinoma metastasizing to duodenum: A rare occurrence. Diagn. Pathol. 2006, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, G.J.; Anderson, M.R.; Moss, M.S.; Wilson, P.G. Metastases from renal cell carcinoma presenting as gastrointestinal bleeding: Two case reports and a review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, R.; Greaney, P.J.; Witkiewicz, A.; Kennedy, E.P.; Yeo, C.J. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the duodenum: Treatment by classic pancreaticoduodenectomy and review of the literature. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2008, 12, 1465–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.K.; Dhar, V. Unremitting upper GI bleeding from a duodenal mass. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 42–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, M.; Ryan, B.; Swan, N.; McDermott, R.S. A Case of Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Presenting as Jaundice. World J. Oncol. 2010, 1, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lu, N.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, L. Duodenal metastases of renal cell carcinoma: A case report. Chin. Med. J. 2010, 123, 1228–1229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rustagi, T.; Rangasamy, P.; Versland, M. Duodenal bleeding from metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2011, 5, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherian, S.V.; Das, S.; Garcha, A.S.; Gopaluni, S.; Wright, J.; Landas, S.K. Recurrent renal cell cancer presenting as gastrointestinal bleed. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2011, 3, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chara, L.; Rodríguez, B.; Holgado, E.; Ramírez, N.; Fernández-Rañada, I.; Mohedano, N.; Arcediano, A.; García, I.; Cassinello, J. An unusual metastatic renal cell carcinoma with maintained complete response to sunitinib treatment. Case Rep. Oncol. 2011, 4, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zhu, Y.-F.; Shen, L.-G. Surgical treatment of renal cell carcinoma metastasized to the duodenum. Chin. Med. J. 2012, 125, 3198–3200. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, A.; Littler, Y.; Libertiny, G. Asymptomatic renal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and duodenum: A case report and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2012, 2012, bcr0220125764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Han, K.; Li, J.; Liang, P.; Zuo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. A case of wedge resection of duodenum for massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to duodenal metastasis by renal cell carcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Yang, Y.C.; Li, M.H.; Kuo, H.C.; Lee, M.C. Complete metastasectomy to treat simultaneous metastases of the duodenum and pancreas caused by renal cell carcinoma. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2011, 24, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlussel, A.T.; Fowler, A.B.; Chinn, H.K.; Wong, L.L. Management of locally advanced renal cell carcinoma with invasion of the duodenum. Case Rep. Surg. 2013, 2013, 596362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalo-Marín, J.; Aguilar-Urbano, V.M.; Muñoz-Castillo, F.; Albandea-Moreno, C.; Montes-Aragón, C.; de-Sola-Earle, C. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to renal tumor. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2012, 104, 614–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashi, P.G.; Abboud, E.; Gupta, D. Renal cell carcinoma with unusual metastasis to the small intestine manifesting as extensive polyposis: Successful management with intraoperative therapeutic endoscopy. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2011, 5, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teli, M.A.; Shah, O.J.; Jan, A.M.; Khan, N.A. Duodenal metastasis from renal cell carcinoma presenting as gastrointestinal bleed. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 15, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakatsanis, A.; Vezakis, A.; Fragulidis, G.; Staikou, C.; Carvounis, E.E.; Polydorou, A. Obstructive jaundice due to ampullary metastasis of renal cell carcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, T.; Sakata, N.; Aoki, T.; Yoshida, H.; Kanno, A.; Fujishima, F.; Motoi, F.; Masamune, A.; Shimosegawa, T.; Unno, M. Repeated pancreatectomy for metachronous duodenal and pancreatic metastases of renal cell carcinoma. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2013, 7, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neofytou, K.; Giakoustidis, A.; Gore, M.; Mudan, S. Emergency Pancreatoduodenectomy with Preservation of Gastroduodenal Artery for Massive Gastrointestinal Bleeding due to Duodenal Metastasis by Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma in a Patient with Celiac Artery Stenosis. Case Rep. Surg. 2014, 2014, 218953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidong, W.; Jianwei, W.; Guizhong, L.; Ning, L.; Feng, H.; Libo, M. Ampullary tumor caused by metastatic renal cell carcinoma and literature review. Urol. J. 2014, 11, 1504–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Wu, S.T.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, H.M. Metachronous duodenal metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 34, 186–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M.O.; Al-Rubaye, S.; Reilly, I.W.; McGoldrick, S. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as an upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2015211553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vootla, V.R.; Kashif, M.; Niazi, M.; Nayudu, S.K. Recurrent Renal Cell Carcinoma with Synchronous Tumor Growth in Azygoesophageal Recess and Duodenum: A Rare Cause of Anemia and Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Case Rep. Oncol. Med. 2015, 2015, 143934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geramizadeh, B.; Mostaghni, A.; Ranjbar, Z.; Moradian, F.; Heidari, M.; Khosravi, M.B.; Malekhosseini, S.A. An unusual case of metastatatic renal cell carcinoma presenting as melena and duodenal ulcer, 16 years after nephrectomy; a case report and review of the literature. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 40, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jideh, B.; Chen, H.; Weltman, M.; Chan, C.H.Y. Metastatic periampullary clear cell renal carcinoma. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 83, 1040–1042, discussion 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarocchi, F.; Gilg, M.M.; Schreiber, F.; Langner, C. Secondary tumours of the ampulla of Vater: Case report and review of the literature. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 8, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, M.; Senjo, H.; Kanaya, M.; Izumiyama, K.; Mori, A.; Tanaka, M.; Morioka, M.; Miyashita, K.; Ishida, Y. Late duodenal metastasis from renal cell carcinoma with newly developed malignant lymphoma: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 8, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omranipour, R.; Mahmoud Zadeh, H.; Ensani, F.; Yadegari, S.; Miri, S.R. Duodenal Metastases from Renal Cell Carcinoma Presented with Melena: Review and Case Report. Iran. J. Pathol. 2017, 12, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villela-Segura, U.; García-Leiva, J.; Nuñez Becerra, P.J. Duodenal metastases from sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: Case report. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 40, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podboy, A.; Shah, N. The Past Is Never Past: An Unusual Cause of Melena. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, e3–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatavicius, P.; Lizdenis, P.; Pranys, D.; Gulbinas, A.; Pundzius, J.; Barauskas, G. Long-term Survival of Patient with Ampulla of Vater Metastasis of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Prague Med. Rep. 2018, 119, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, I.; Muslim, A.; Jurčić, P.; Nikolic, M.; Budimir, I. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma as a rare cause of duodenal obstruction and gastrointestinal bleeding. Acta Med. Croat. 2018, 72, 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T.; Oe, N.; Matsumori, T. A Hypervascular Mass at the Papilla of Vater. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, e7–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, A.; Khan, A.M.; McCarthy, L.; Mehdi, S. An Unusual Case of Renal Cell Carcinoma Metastasis to Duodenum Presenting as Gastrointestinal Bleeding. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrokh, D.; Rad, M.P.; Mortazavi, R.; Akhavan, R.; Abbasi, B. Local recurrence of renal cell carcinoma presented with massive gastrointestinal bleeding: Management with renal artery embolization. CVIR Endovasc. 2019, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghmar, S.; Shasthry, S.M.; Singla, R.; Patidar, Y.; Bihari, C.B.; Sarin, S.K. Solitary duodenal metastasis from renal cell carcinoma with metachronous pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: Review of literature with a case discussion. Indian J. Med. Paediatr. Oncol. 2019, 40, S185–S190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-H.; Kang, S.-B.; Lee, S.-M.; Park, J.-S.; Kim, D.-W.; Ahn, S. Randomized controlled trial of tamsulosin for prevention of acute voiding difficulty after rectal cancer surgery. World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 2730–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, N.; Lightner, C.; McCaffrey, J. An Unusual Case of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Case Rep. Oncol. 2020, 13, 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Meyer, C.P.; Karam, J.A.; de Velasco, G.; Chang, S.L.; Pal, S.K.; Trinh, Q.-D.; Choueiri, T.K. Predictors, utilization patterns, and overall survival of patients undergoing metastasectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the era of targeted therapy. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabestani, S.; Marconi, L.; Hofmann, F.; Stewart, F.; Lam, T.B.L.; Canfield, S.E.; Staehler, M.; Powles, T.; Ljungberg, B.; Bex, A. Local treatments for metastases of renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e549–e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dr Hall, B.; Abel, E.J. The Evolving Role of Metastasectomy for Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 47, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psutka, S.P.; Master, V.A. Role of metastasis-directed treatment in kidney cancer. Cancer 2018, 124, 3641–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, G.; Raimondi, A.; Verzoni, E.; Claps, M.; Sepe, P.; Pagani, F.; Ratta, R.; Montorsi, F.; De Braud, F.G.M.; Procopio, G. The role of metastasectomy in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2019, 19, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.P.; Sun, M.; Karam, J.A.; Leow, J.J.; de Velasco, G.; Pal, S.K.; Chang, S.L.; Trinh, Q.-D.; Choueiri, T.K. Complications After Metastasectomy for Renal Cell Carcinoma-A Population-based Assessment. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaen-Torrejimeno, I.; Rojas-Holguín, A.; López-Guerra, D.; Ramia, J.M.; Blanco-Fernández, G. Pancreatic resection for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. A systematic review. HPB 2020, 22, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.K.H.; Chuah, K.L. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma to the Pancreas: A Review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch-Nyhan, A.; Fishman, E.K.; Kadir, S. Diagnosis and management of massive gastrointestinal bleeding owing to duodenal metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 1987, 138, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Gender, Age | Clinical Presentation | Biological Abnormalities | CT SCAN | Endoscpîc Aspect/Localisation | Histological Proof of Renal Carcinoma | Nephrectomy Side | Delay After Nephrectomy | Treatment | Patient Outcome | Other Localization | Operated Patients- Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black, 1995 [7] | F, 60 years | Melena | Severe anemia | Mass invading pancreas | Periampullary lesion | Surgical sample | Right | Metachronous-6 years | Surgery | - | ||

| Hsu, 1996 [8] | F, 54 years | Melena, anemia | Anemia | - | Second duodenum-polypoid mass | Endoscopic biopsy | - | Metachronous-1.5 years | Chemotherapy | Dead at 1 month | - | |

| Hsu, 1996 [8] | F, 72 years | Melena, anemia | Anemia | Localized right renal tumor | Second duodenum-Submucosal mass with ulcerations | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-1 year | Treatment refused | Lost to follow up | Bone | |

| Leslie, 1996 [9] | M, 53 years | Melena, weight loss | Bilirubin increase | Periampullary lesion | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous 8 years | PD | Alive at 2.5 years | - | No complication | |

| Toh, 1998 [10] | F, 59 years | Lethargy, abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, iron suplementation for chronic anemia | Anemia | Solid mass on the posterior wall of Duodenum | Normal | Surgical sample | Right | Metachronous-10 years | Wedge resection | - | - | Gastroplegia |

| Janzen, 1998 [11] | M, 75 years | Melena, bleeding necessitating ressucitation | Severe anemia | Perimapullary mass extending to head of the pancreas | Periampullary mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-18 years | - | |||

| Yavascaoglu, 1999 [12] | M, 63 years | Right flank pain, melena | - | Right renal tumor of 15 × 14 cm and pancreatico-duodenal mass 7 × 5 cm | Hemorrhagic area on the second duodenum | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Synchronous | PD + interferon-Nephrectomy | Alive at 23 months | - | - |

| Ohmura, 2000 [13] | M, 62 years | Occlusion | Enhanced mass of renal fossa invading psoas muscle and duodenum | Large elvated irregular shaped tumor, obstructive | Surgical sample | Left | Metachronous-5 years | Wedge resection | Dead at 1 month | Lung (surgery) | Peritonitis/bleeding at day-40: death | |

| Hashimoto, 2001 [14] | M, 68 years | Dyspnea | Severe anemia | Wall thickening | Ulcerated tumor on duodenal bulb | Surgical sample | Left | Metachronous-11 years | PD | Alive at 18 months | - | No complication |

| Lee, 2002 [15] | F, 76 years | Dyspepsia, abdominal pain, lump on upper right abdomen | - | Wall thickening | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-4 years | Medical treatment | Alive at 1 year | - | ||

| Loualidi, 2004 [16] | M, 76, years | Weakness, dizziness, dyspnea, epigastric discomfort | Anemia | - | Periampullary–lobular mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-5 years | Paliative radiotherapy | Alive at 1 year | L5 | |

| Chang, 2004 [17] | F, 63 years | 4 episodes of bleeding in 9 months | Severe anemia | - | Duodenal bulb-ulcerative mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-9 years | Surgery | Alive at 10 months | - | No complication |

| Bhatia, 2006 [18] | M, 55 years | Jaundice, abdominal lump | Cytolysis, cholestasis | No mass | Second duodenum-submucosal lesion | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-1 year | Paliative radiotherapy | Lost to follow up | Liver | |

| Sadler, 2007 [19] | M, 67 years | Melaena, lethargyy, recurent anemia ++ | Severe anemia | Polypoid mass, in the medial wall of D2 arising from pancreas & renal mass | Angulus-polyp | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Synchronous | Nephrectomy + interferon | Dead 2 years | Lung & adrenal gland left | |

| Sadler, 2007 [19] | M, 75 years | Chronic anemia | - | Pancreatic mass invading duodenum | Duodenal bulb-polyp | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-9 years | No treatment | - | - | |

| Adamo, 2008 [20] | M, 86 years | Obstruction & anemia | - | Duodenal mass invading pancreas | - | Surgical sample | - | Metachronous-13 years | PD | Alive at 7 months | - | Pulmonary embolism |

| Das, 2009 [21] | M, 68 years | Hematochezia | Anemia | - | Second duodenum-large friable, centrally ulcerated mass | Endoscopic biopsy | - | Metachronous-10 years | PD | Alive at 4 months | Lung | |

| Teo, 2010 [22] | M, 50 years | Jaundice, abdominal pain | Cholestasis, cytolysis, bilirubin increase | Dilatation of the biliary duct | periampullary-mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-3 years | Antiangiogenics | 1 week | Lung | |

| Kanthan, 2010 [3] | M, 69 years | Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | - | - | - | Endoscopic biopsy | - | Metachronous-8 years | - | - | - | |

| HE, 2010 [23] | M, 62 years | Massive melena | Anemia, elevated CA 19-9 and ACE | Submucous tumor | Bleeding mass second duodenum | Surgical sample | Right | Metachronous-11 years | PD | Alive at 17 months | - | Gastroplegia |

| Rustagi, 2011 [24] | M, 66 years | Melena, anemia, fatigue | Severe anemia | Mass | Second duodenum-actively bleeding and ulcerative mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Bilateral | Metachronous-13 years | PD | Dead at 2 weeks | - | Leakage of pancreaticojejunostomy fistula-sepsis |

| Cherian, 2011 [25] | M, 80 years | Syncope, melena | Severe anemia | Soft tissue mass extending in duodenum from right nephrectomy bed | Second duodenum | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-1 years | Sorafenib, everolimus | Dead at 1 year | Lumbar vertebra-lung | |

| Chara, 2011 [26] | M, 49 years | Melena | Enlargement of the head of the pancreas | Duodenal ulcer initially treated by sclerotherapy and biopsied 5 months after diagnosis | Surgical sample | Left | Metachronous-6 years | PD | Alive at 4 years | - | No complication | |

| Yang, 2012 [27] | F, 72 years | Melena, fatigue, hematemesis | Severe anemia | - | Mass at second portion of duodenum bleeding and necrosis | Surgical sample | Left | Metachronous-10 years | Wedge resection | Recurrence at 10 months | - | Surgical site infection-Pulmonary infection |

| Mandal, 2012 [28] | F, 60 yars | Melena-diarrhea | Nothing | No lesion on CT Scan | Second duodenum-abnormal duodenal border | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Synchronous | Nephrectomy + chemotherapy | - | Skin | |

| Zhao, 2012 [29] | M, 56 years | Occlusion-bleeding-fatigue | Severe anemia | filling defect | Second duodenum-ulcerated and hemorrhagic mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-7 years | Wedge resection | Alive at 1.5 years | Tail pancreatic lump non operated | No complication |

| Chen, 2012 [30] | F, 76 years | Hematoschzia, anemia | Anemia | Hypervascular lesion involving duodenum, pancreas gastric antrum | First duodenum-submucosal mass involving stomach | Surgical sample | Left | Metachronous-6 years | PD | Aliver at 24 months | - | No complication |

| Schlussel, 2012 [31] | M, 53 years | Melana, fatigue, | Severe anemia | Large mass (15 cm) arising of right kidney protruding into duodenum lumen | Second duodenum -bleeding mass | Surgical sample | Right | Synchronous | Nephrectomy + PD + thrombectomy + IL-2 | Alive at 3 months | Lung | No complication |

| Gonzalo-Marin, 2012 [32] | M, 66 years | Melena | Anemia | Necrotic right renal mass with duodenum invasion-bile duct dilatation | Second duodenum-large and deep ulceration with edematous borders | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous | - | - | Paraaortic LN-lUng | - |

| Vashi, 2012 [33] | M, 53 years | Dyspnea | Severe anemia | Right renal lesion | First duodenum-2 small vascular polyps | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous | Duodenotomy | Small intestine polyps | No complication | |

| Ashraf Teli, 2012 [34] | M, 52 years | Gastro intestinal bleeding | Duodenal metastasis | Duodenal mass, bleeding | Surgical sample | Right | Metachronous-8 years | Duodenotomy | Died at 4 months | - | No complication | |

| Karakatsanis, 2013 [35] | M, 77 years | Isolated jaundice | - | Dilatation of the biliary duct | Ampula-massI25 | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-3 years | Ampullectomy + biliary stent | Dead at 1.5 year | Lung/bone | |

| Hata, 2013 [36] | M, 50 years | Anemia, melena | Severe anemia | Second duodenum-Ulcerated polypoid mass (not involving ampulla); NBIde,se assembly of microvessels | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-15 years | PD | Alive at 1 year | Bone (radiotherapy)-pancreas tail (surgery) | Leakage of gastrojejunostomy | |

| Neofytou, 2014 [37] | M, 41 years | Massive GI bleeding | Anemia | - | Vater ampula | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-1 year | Initially under pazopanib, PD for emergency | Dead at 2 months | Adrenal gland bilatera, thoracic lymphnodes | |

| Espinoza,2014 [5] | M, 58 years | Gastro intestinal bleeding | - | - | - | - | Right | Metachronous-12 years | PD | Alive at 12 months | - | |

| Espinoza,2014 [5] | F, 66 years | Abdominal pain | - | - | - | - | Right | Metachronous-4 years | PD | Alive at 12 months | - | |

| Haidong, 2014 [38] | M, 50 years | Fatigue–fever– diarrhea | Bilirubin increase-Cholestasis- moderate cytolysis | Presence of tumor | No endoscopy | Surgical sample | Right | Synchronous | PD + Radical nephrectomy FN alph-2b | Alive at 5 years | - | No complication |

| Hu, 2014 [39] | M, 57 years | Dyspnea, dyspepsia, fatigue, anemia, melena | Severe anemia | Intraluminal enhancing lesion 6 cm | Bulb/second duodenum-polypoid ulcerative and friable mass bleeding with obstruction | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-12 years | PD + sunitinib | Alive at 6 months | - | No complication |

| Osama Mohamed, 2015 [40] | M, 80 years | Melena, abdominal pain, dyspnea | Anemia | 8 cm mass lower pole of kidney invading duodenum | polypoidal mass anterior second duodenum bleeding | - | Right | Synchronous | Palliative treatment | - | - | |

| Vootla, 2015 [41] | M, 74 years | Melena, weight loss | Anemia | Duodenal nodule | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-4 years | Paliative radiotherapy | - | Oesophagus | ||

| Geramizadeh, 2015 [42] | M, 61 years | Melena | Normal | Mass invading duodenum and pancreas | Second duodenum-ulcer aspect | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-16 years | PD | - | No complication | |

| Jideh, 2016 [43] | M, 50 years | Fever-abdominal pain-jaundice | Bilirubin increase-cholestasis | Biliary duct dilatation-no mass shown | Periampullary-mucosal mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous | - | - | - | |

| Sarocchi, 2016 [44] | M, 57 years | GI bleeding | Vater ampula irregular | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-3.5 years | PD | Alive a 4 years | - | No complication | ||

| Saito, 2017 [45] | M, 64 years | Abdominal pain, fever, anorexia, weight loss | - | Hypervaslucar lesion duodenum and pancreatic head | Second duodenum apart form apula-submucosal mass with central ulcer | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-25 years | Pazopanib | - | Concomitant lymphoma treated-lung | |

| Omranipour, 2017 [46] | M, 59 years | Melena | Anemia | Mass in nephrectomy bed invading D2 and D3 | Irregular, polypoid, ulcerative mass in second portion of duodenum | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-6 years | PD | Alive a 1 year | - | No complication |

| Villela-Segura, 2018 [47] | F, 48 years | Burning and sharp epigastric pain, hematemesis, melena, fever, hypotension | Severe anemia | Mass in the second portion of duodenum | Mass at second portion of duodenum, submucosal, ulcerated surface, bleeding, 90% of stenosis | Endoscopic biopsy | - | Metachronous-1 year | - | Dead at 1 week | - | |

| Podboy, 2018 [48] | M, 80 years | Melena | - | Hypervascularized mass of pancreas and duodenum | Ulcerated mass | Endoscopic biopsy | - | Metachronous-15 years | - | - | - | |

| Ignatavicius, 2018 [49] | M, 62 years | Severe upper abdominal pain, jaundice, lethargy, subclinical obstruction | Bilirubin increase | Periampummary mass, pancreatic and bile duct dilatation | Tumor at paiplla | Surgical sample | Left | Metachronous-8 months | PD | Dead at 14 months | - | No complication |

| Popovic, 2018 [50] | M, 58 years | Occlusion-bleeding | Anemia | Third duodenum-obstructive mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Left | Metachronous-7 months | Endoscopic thermocoagulation | Dead at 4 years | - | ||

| Nakamura, 2019 [51] | M, 74 years | Vomiting, orthostatic fainting | Severe anemia | EUS: biliary duct dilatation and hypoechogenic mass | EUS biopsy | Right | Metachronous | - | - | - | No complication | |

| Munir, 2019 [52] | M, 76 years | Asymptomatic-diagnosis at following | - | Mass | Second duodenum-friable mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-2 years | Sunitinib-nivolumab | - | - | |

| Farrokh, 2019 [53] | M, 62 years | Fatigue, weigh loss, massive gastrointestinal bleeding | Mass in nephrectomy bed invading D2 and D3 | Second duodenum-irregular ulcerative mass | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-10 years | Embolization-axitinib | - | - | ||

| Baghmar, 2019 [54] | M, 84 years | Fatigue, anemia, diarrhea | Severe anemia | Mass with central necrosis | First/second duodenum junction-ulcerations | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-37 years | Palliative treatment | - | ||

| Jain, 2020 [55] | M, 73 years | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, hypertension, abdominal tenderness, anemia | Severe anemia | Lymph nodes in pancreaticoduodenal, para-aortic, precaval regions | Periampullary-ulcer | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-33 years | Immunotherapy | - | LN | - |

| Peters, 2020 [56] | M, 68 years | Dyspnea, fatigue, anemia | Severe anemia | - | Second duodenum-polyp | Endoscopic biopsy | Right | Metachronous-1.5 years | Embolization-axitinib | Bones, live, LN |

| Feature | n | Average/Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female ratio | 55 | 4/1 | |

| Average age | 55 | 64 years | |

| Metachronous vs. synchronous | 55 | ||

| Metachronous | 49 | 89% | |

| DFI (median) | 45 | 7 years | |

| Synchronous | 6 | 11% | |

| RCC side | 48 | ||

| Bilateral | 1 | 2% | |

| Left | 19 | 40% | |

| Right | 28 | 58% | |

| Symptoms | 54 | 55 | 98% |

| Lethargy–general symptoms | 22 | 40% | |

| Occlusion | 5 | 9% | |

| Abdominal pain | 10 | 18% | |

| Bleeding (upper and lower) | 36 | 65% | |

| Upper GI bleeding | 12 | 22% | |

| Lower bleeding (Melena, hematoschezia) | 26 | 47% | |

| Anemia | 32 | 58% | |

| Fever | 4 | 7% | |

| Jaundice-cholestasis | 5 | 9% | |

| Other metastasis site | 20 | 55 | 36% |

| Localization of the tumor | 44 | ||

| Second duodenum | 35 | 80% | |

| Periampullary | 12 | 27% | |

| Angulus | 2 | 5% | |

| First Duodenum | 6 | 14% | |

| Third duodenum | 1 | 2% | |

| Treatment | 48 | ||

| Surgery alone | 23 | 48% | |

| Medical therapy alone | 11 | 23% | |

| Surgery + medical therapy | 5 | 10% | |

| Paliative RT | 3 | 6% | |

| No treatment | 6 | 13% | |

| Overall Survival-Median | 48 months |

| Surgery (n = 28) | No Surgery (n = 20) | n | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median | 60.5 [55.2; 66.0] | 70.0 [59.5; 76.0] | 48 | 0.028 | |

| Sex (Male proportion) | 22 (79%) | 16 (80%) | 38 | 1 | |

| DFI, median | 8.00 [6.00; 11.0] | 4.00 [1.50; 9.25] | 41 | 0.067 | |

| Bleeding/anemia | 22 (79%) | 15 (75%) | 37 | 1 | |

| Localisation | D2 | 16 (80%) | 14 (74%) | 30 | 0.35 |

| D1 | 4 (20%) | 2 (11%) | 6 | ||

| ANGULUS | 0 (0%) | 2 (11%) | 2 | ||

| D3 | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 | ||

| Metachronous metastasis | 25 (89%) | 17 (85%) | 42 | 0.68 | |

| Nephrectomy side | Right | 16 (57%) | 10 (50%) | 26 | 0.88 |

| Left | 9 (32%) | 9 (45%) | 18 | ||

| Bilateral | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 | ||

| Other metastasis localisation, n | 18 (64%) | 15 (75%) | 33 | 0.43 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taha, F.; Rhaiem, R.; Larre, S.; Kianmanesh, A.R.; Renard, Y.; Acidi, B. Renal Cell Carcinoma with Duodenal Metastasis: Is There a Place for Surgery? A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7189. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207189

Taha F, Rhaiem R, Larre S, Kianmanesh AR, Renard Y, Acidi B. Renal Cell Carcinoma with Duodenal Metastasis: Is There a Place for Surgery? A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7189. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207189

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaha, Fayek, Rami Rhaiem, Stephane Larre, Ali Reza Kianmanesh, Yohan Renard, and Belkacem Acidi. 2025. "Renal Cell Carcinoma with Duodenal Metastasis: Is There a Place for Surgery? A Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7189. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207189

APA StyleTaha, F., Rhaiem, R., Larre, S., Kianmanesh, A. R., Renard, Y., & Acidi, B. (2025). Renal Cell Carcinoma with Duodenal Metastasis: Is There a Place for Surgery? A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7189. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207189