The Significance of Palliative Care in Managing Pain for Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. Pain Assessment

- -

- Provokes: What makes the pain worse?

- -

- Palliates: What helps relieve the pain?

- -

- Quality: What is the nature of the pain?

- -

- Region: Where is the most intense pain located?

- -

- Radiation: Where does the pain radiate?

- -

- Severity: How intense is the pain? This is typically measured using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

- -

- Time: When does the pain occur?

2.4. Factors Triggering Pain

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Future Prospects

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kitala-Tańska, K.; Kania-Zimnicka, E.; Tański, D.; Kwella, N.; Stompór, T.; Stompór, M. Prevalence and Management of Chronic Pain, Including Neuropathic Pain, in Dialysis Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e943808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, S.N.; Jhangri, G.S. Impact of pain and symptom burden on the health-related quality of life of hemodialysis patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 39, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, S.L.; Scherer, J.S.; Koncicki, H.M. Kidney Supportive Care: Core Curriculum 2020. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, E.J.R.; Dani, M.; Verberne, W.R.; Van Den Noortgate, N.J.; Joosten, H.M.H.; Brys, A.D.H. Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease: A Key to Personalized Care and Shared Decision-Making—A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, F.K.; Novara, G.; Nalesso, F.; Calò, L.A. Conservative Management in End-Stage Kidney Disease between the Dialysis Myth and Neglected Evidence-Based Medicine. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanini, I.; Samoni, S.; Husain-Syed, F.; Fabbri, S.; Canzani, F.; Messeri, A.; Mediati, R.D.; Ricci, Z.; Romagnoli, S.; Villa, G. Palliative Care for Patients with Kidney Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S.; Varghese, A.; Snead, C.M.; Hole, B.D.; O’Hara, D.V.; Agarwal, N.; Stallworthy, E.; Caskey, F.J.; Smyth, B.J.; Ducharlet, K. A Multinational, Multicenter Study Mapping Models of Kidney Supportive Care Practice. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 2198–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.L.; Panizza, N.; Bartlett, R.; Martin-Robins, D.; Brown, J.A. A period prevalence study of palliative care need and provision in adult patients attending hospital-based dialysis units. J. Nephrol. 2025, 38, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szigeti, N.; Tóth, S.; Kun, S.; Ladányi, E.; Csiky, B.; Wittmann, I. A dializált betegek palliatív ellátása = Palliative care of patients treated by dialysis. Hypertonia Nephrol. 2024, 28, 187–189. [Google Scholar]

- ALHosni, F.; Al Qadire, M.; Omari, O.A.; Al Raqaishi, H.; Khalaf, A. Symptom prevalence, severity, distress and management among patients with chronic diseases. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursic, A.E.; Schell, J.O. Hospice Care in Conservative Kidney Management. Semin. Nephrol. 2023, 43, 151398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahlkamp, A.; Schneider, J.; Markossian, T.; Balbale, S.; Ray, C.; Stroupe, K.; Limaye, S. Nephrology-Palliative Care Collaboration to Promote Outpatient Hemodialysis Goals of Care Conversations. Fed. Pract. 2023, 40, 349–351a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darawad, M.W.; Reink, L.F.; Khalil, A.; Melhem, G.B.; Alnajar, M. Palliative Care for Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease: An Examination of Unmet Needs and Experiencing Problems. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2025, 27, E107–E117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.M.; Tsai, H.B.; Chen, Y.C.; Hung, K.Y.; Cheng, S.Y.; Lin, C.P. Palliative Care for Adult Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis in Asia: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2024, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.H.; Holley, J.L.; Davison, S.N.; Dart, R.A.; Germain, M.J.; Cohen, L.; Swartz, R.D. Palliative care. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004, 43, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, E.; Haggiag, I.; Os, P.; Bernheim, J. Calcium, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D: Major determinants of chronic pain in hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleishman, T.T.; Dreiher, J.; Shvartzman, P. Pain in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: A Multicenter Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, 78–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantinga, L.C.; Fink, N.E.; Jaar, B.G.; Huang, I.C.; Wu, A.W.; Meyer, K.B.; Powe, N.R. Relation between level or change of hemoglobin and generic and disease-specific quality of life measures in hemodialysis. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouattar, T.; Skalli, Z.; Rhou, H.; Ezzaitouni, F.; Ouzeddoun, N.; Bayahia, R.; Benamar, L. The evaluation and analysis of chronic pain in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Ther. 2009, 5, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizher, A.; Hammoudi, H.; Hamed, F.; Sholi, A.; AbuTaha, A.; Abdalla, M.A.; Jabe, M.M.; Hassan, M.; Koni, A.A.; Zyoud, S.H. Prevalence of chronic pain in hemodialysis patients and its correlation with C-reactive protein: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouq, M.K.; Samoudi, A.F.; Samara, A.; Zyoud, S.H.; Al-Jabi, S.W. Exploring factors associated with pain in hemodialysis patients: A multicenter cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsurer, R.; Afsar, B.; Mercanoglu, E. Bone pain assessment and relationship with parathyroid hormone and health-related quality of life in hemodialysis. Ren. Fail. 2013, 35, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, R.; Krishnappa, V.; Gupta, M. Management of pain in end-stage renal disease patients: Short review. Hemodial. Int. 2018, 22, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Mohamed, I.A.; Shahin, M.A.; Abd-El Hady, T.R.M.; Abdelhalim, E.H.N.; Zaghami, D.E.F.; Anwr Akl, D.B.; Ghazy Mohammed, L.Z.; Moustafa Ahmed, F.A. Evaluating palliative care’s role in symptom management for CKD patients in Egypt: A quasi-experimental approach. Palliat. Support. Care 2025, 23, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, A.; Gwyther, E. Pain management in palliative care. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2006, 48, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, S.N. Pain in hemodialysis patients: Prevalence, cause, severity, and management. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 42, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, R.A.H.; Brom, L.; Theunissen, M.; van den Beuken-van Everdingen, M.H.J. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, D.; Satta, E.; Messina, S.; Costantino, G.; Savica, V.; Bellinghieri, G. Pain in end-stage renal disease: A frequent and neglected clinical problem. Clin. Nephrol. 2013, 79 (Suppl. S1), S2–S11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, P.R.; Mendonça, C.R.; Hernandes, J.; Borges, C.C.; Barbosa, M.A.; Romeiro, A.M.S.; Alves, P.M.; Dias, N.T.; Porto, C.C. Pain in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2021, 22, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.S. Treating pain to improve quality of life in end-stage renal disease. Semin. Dial. 2013, 26, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Liu, H.R.; Kong, Q.; Gan, J.Y.; Liu, K.; Yao, W.G.; Yao, X.M. Effect of Acupuncture Intervention on Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Hemodialysis-Dependent Kidney Failure Patients: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Pain Res. 2024, 17, 4289–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Parola, V.; Cardoso, D.; Bravo, M.E.; Apóstolo, J. Use of non-pharmacological interventions for comforting patients in palliative care: A scoping review. JBI Database System. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2017, 15, 1867–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, A.; Di Iorio, B.; Guastaferro, P.; Bahner, U.; Heidland, A.; De Santo, N. High-tone external muscle stimulation in end-stage renal disease: Effects on symptomatic diabetic and uremic peripheral neuropathy. J. Ren. Nutr. 2008, 18, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güvener, Y.Ö.; Koç, Z. The effect of breathing exercises on pain, sleep, and symptom management in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep Breath 2025, 29, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KauricKlein, Z. Effect of yoga on physical and psychological outcomes in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 34, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, S.N.; Rathwell, S.; George, C.; Hussain, S.T.; Grundy, K.; Dennett, L. Analgesic Use in Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2020, 7, 2054358120910329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalim, S.; Lyons, K.S.; Nigwekar, S.U. Opioids in Hemodialysis Patients. Semin. Nephrol. 2021, 41, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayev, L.Y.; Mor, M.K.; Sevick, M.A.; Shields, A.M.; Rollman, B.L.; Palevsky, P.M.; Arnold, R.M.; Fine, M.J.; Weisbord, S.D. Longitudinal associations of depressive symptoms and pain with quality of life in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Hemodial. Int. 2015, 19, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliuk-Ben Bassat, O.; Brill, S.; Sharon, H. Chronic pain is underestimated and undertreated in dialysis patients: A retrospective case study. Hemodial. Int. 2019, 23, E104–E105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, Y.S.; Eidemak, I.; Larsen, S.; Sjøgren, P.; Molsted, S.; Sørensen, J.; Laursen, L.; Kurita, G.P. Identification of palliative care needs in hemodialysis patients: An update. Palliat. Support. Care 2022, 20, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | 159 |

| Age (years) | 65 (±12) |

| Sex (men) | 80 (50%) |

| Pain | |

| Yes | 91 (57%) |

| No | 68 (43%) |

| Severity of Pain (in Several Different Regions) | |

|---|---|

| Mild (NRS 1–3) | 15 (16%) |

| Moderate (NRS 4–6) | 39 (43%) |

| Severe (NRS 7–10) | 41 (45%) |

| Parameter | OR | CI 95% | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 2.296 | 1.019–2.981 | 0.012 |

| HT | 7.932 | 1.207–14.658 | <0.001 |

| DM | 7.375 | 1.917–13.833 | 0.013 |

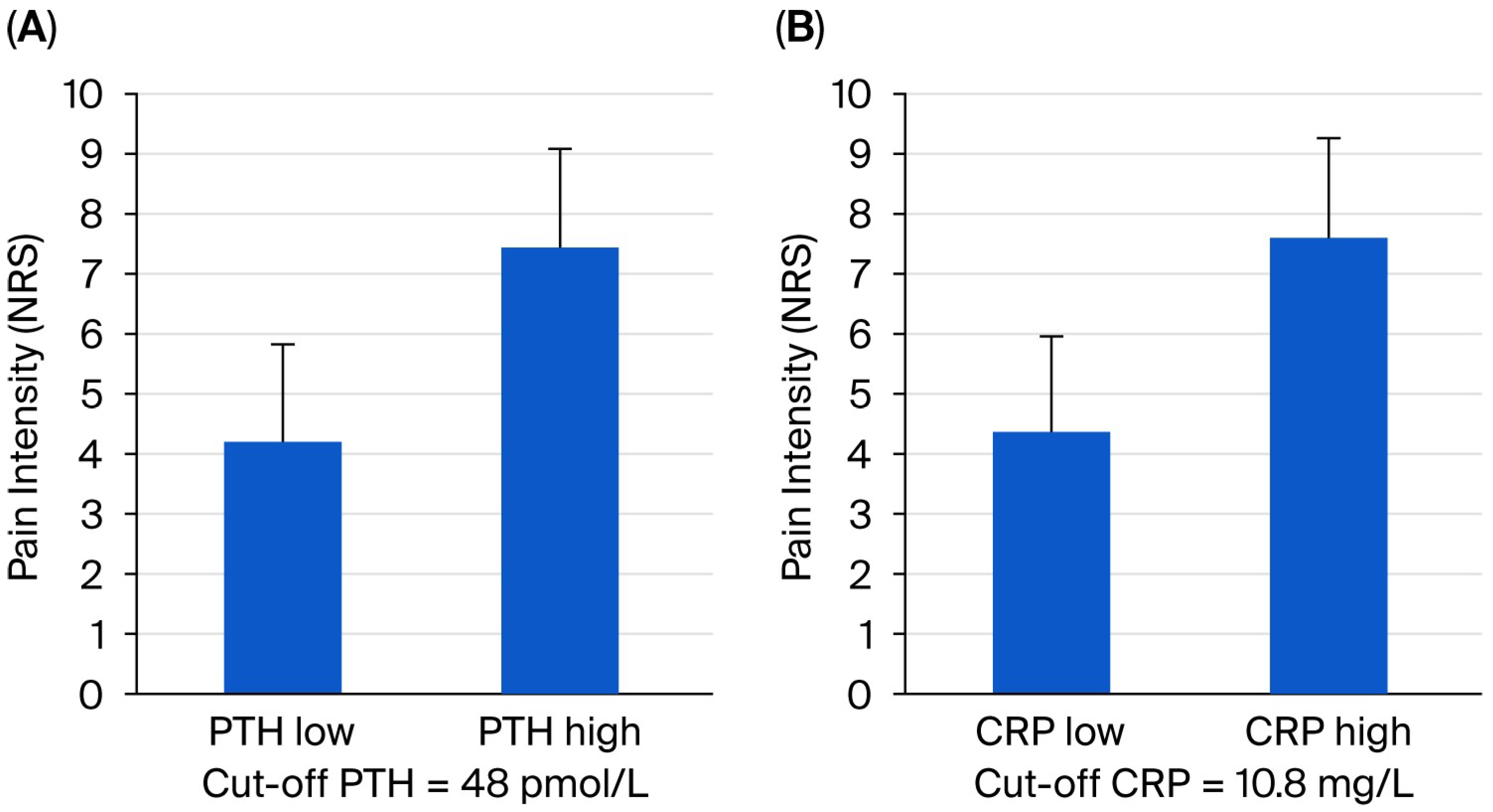

| PTH | 1.578 | 1.089–2.236 | 0.027 |

| Location | |

| Hip/lower limb | 50 (55%) |

| Back | 20 (22%) |

| Shoulder/arm | 20 (22%) |

| Head/neck | 18 (20%) |

| Distal foot | 16 (18%) |

| Waist | 15 (16%) |

| Gluteal region | 10 (11%) |

| Abdomen | 9 (10%) |

| Distal hand | 7 (8%) |

| Chest | 6 (7%) |

| Characteristics | |

| Sharp | 28 (31%) |

| Cramping | 22 (24%) |

| Aching | 22 (24%) |

| Dull | 16 (18%) |

| Numb | 15 (16%) |

| Stabbing | 12 (13%) |

| Throbbing | 8 (9%) |

| Burning | 6 (7%) |

| Aggravating factors | |

| Physical activity | 46 (51%) |

| Rest | 12 (13%) |

| HD | 3 (3%) |

| Weather change | 3 (3%) |

| Meal | 2 (2%) |

| Relieving factors | |

| Rest | 33 (36%) |

| Physical activity | 16 (18%) |

| Negative impact on | |

| Physical activity | 57 (63%) |

| Sleep | 44 (48%) |

| Appetite | 14 (15%) |

| Emotion | 13 (14%) |

| Attention | 10 (11%) |

| Relationship | 5 (5%) |

| Non-Pharmacological Treatment | 0 (0%) |

| Pharmacological treatment (sometimes in combination) | 58 (64%) |

| NSAIDs | 31 (53%) |

| Metamizole | 22 (38%) |

| Paracetamol | 3 (5%) |

| Weak opioid (tramadol) | 13 (22%) |

| Strong opioid | 0 (0%) |

| Adjuvant treatment | 0 (0%) |

| Effectiveness of treatment | |

| No | 1 (2%) |

| Pain relief | 40 (69%) |

| Pain elimination | 17 (29%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szigeti, N.; Csiky, B.; Csikós, Á.; Sági, B. The Significance of Palliative Care in Managing Pain for Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207129

Szigeti N, Csiky B, Csikós Á, Sági B. The Significance of Palliative Care in Managing Pain for Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzigeti, Nóra, Botond Csiky, Ágnes Csikós, and Balázs Sági. 2025. "The Significance of Palliative Care in Managing Pain for Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207129

APA StyleSzigeti, N., Csiky, B., Csikós, Á., & Sági, B. (2025). The Significance of Palliative Care in Managing Pain for Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207129