Assessing Attitudes and Perceptions of High-Risk, Low-Resource Communities Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Public-Access Defibrillation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.2.1. Low-Resource, High-Risk Community

2.2.2. High-Resource, High-Risk Community as a Comparison Group

2.3. Training

- Education (15 min):

- 2.

- Demonstration (10 min):

- 3.

- Hands-on Skills Practice (20 min):

- 4.

- AED and Q&A (15 min):

2.4. Survey Instrument

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Low-Resource, High-Risk Community

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Knowledge Gaps Regarding CPR

3.1.3. Motivation for Training

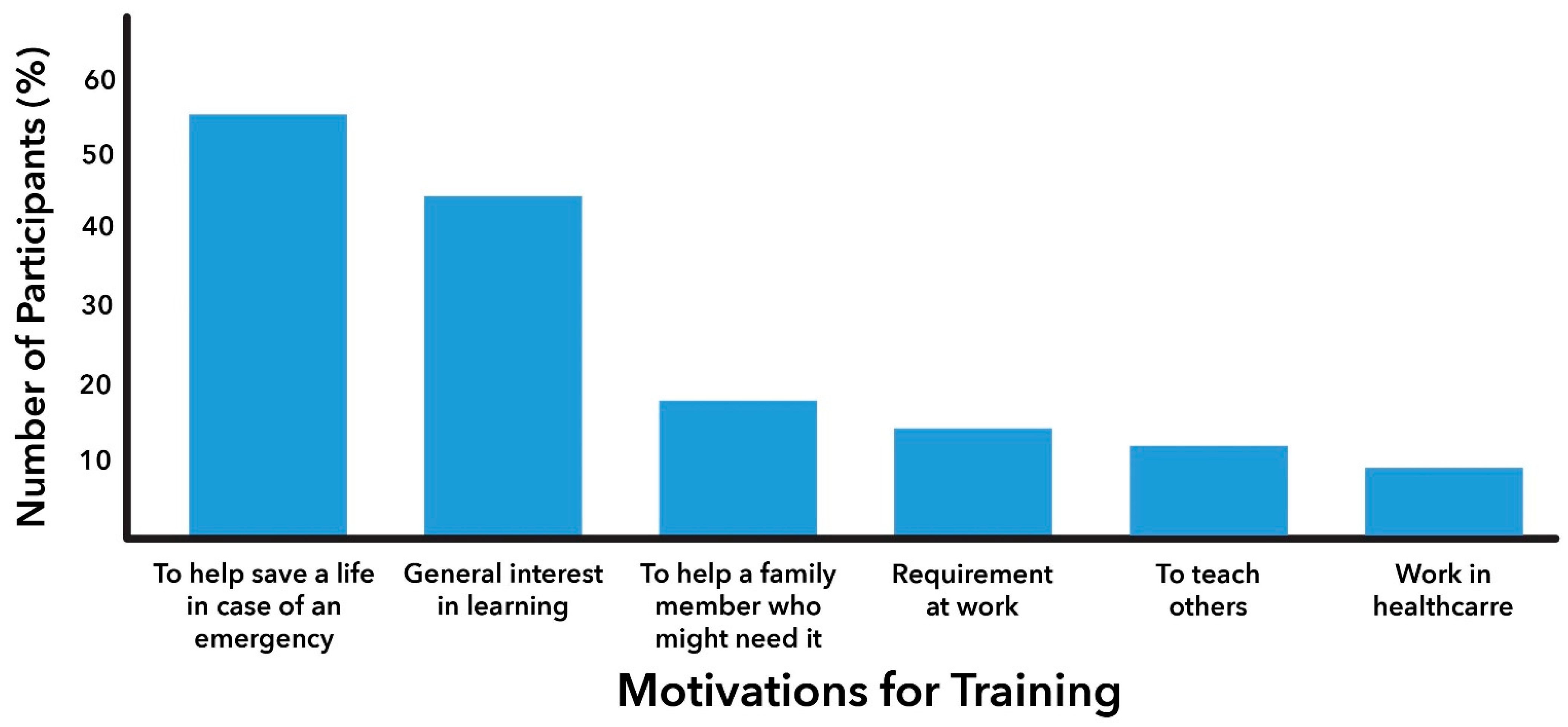

3.1.4. General Concerns with Performing CPR

3.1.5. Factors Influencing Willingness to Perform CPR

3.1.6. Knowledge Gaps and Barriers Associated with the Use of Public Access Defibrillators

3.1.7. Stratified Analysis by Race-Ethnicities

Knowledge Gaps

3.2. Characterizing the High-Resource Community and Comparisons with the Low-Resource Community

3.2.1. Demographics and Knowledge Gaps

3.2.2. Motivation for Training

3.2.3. General Concerns with Performing CPR

3.2.4. General Willingness to Perform CPR

4. Discussion

4.1. Disparities and Cultural Considerations

4.2. Comparison with High-Resource Group

4.3. Implications for Community Interventions and Academic–Community Partnerships

4.4. Strengths

- Collaboration Between Healthcare Institutions and Community Stakeholders: This study highlights the critical importance of building effective partnerships between healthcare institutions and community stakeholders. Central to the project were the partnerships among internal and external partners including various departments and schools within the academic medical center, including the schools of medicine, nursing, and public health, hospital, and community partners, including local middle and high schools. Such collaboration is a prerequisite for designing impactful community-based interventions. Researchers and community-based partners rely on population-based survey data to address health needs and to unravel the “backstory” behind racial/ethnic inequities in health access and outcomes [51]. Population health surveys are uniquely positioned to uplift marginalized populations and serve as tools for health system accountability, especially for those whose risks might otherwise remain obscured in aggregate data [51].

- Multicultural and Multilingual Cohort: The cohort is predominantly Hispanic (64%), and 24% identify as Black, providing a representative multicultural and multilingual sample that mitigates coverage bias. While earlier studies [14,15] employed qualitative interviews to identify barriers and facilitators to CPR and AED use, this study represents the first and largest survey-based investigation assessing the prevalence of these themes in a broad, diverse population.

- Comparison Between Low-and High-Resource Communities: To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the attitudes and perceptions of lay community members in low-resource neighborhoods with those from high-resource settings. The findings indicate that confidence deficits and fears of legal repercussions are prevalent in both groups, suggesting that certain components of future training and intervention programs could potentially apply across all high-risk environments.

- Post-Pandemic Perspective: This study is also unique in its evaluation of lay communities’ attitudes and perceptions in the post-COVID-19 era. The pandemic brought about significant logistical and behavioral changes, making it essential to reassess community barriers before designing and testing community-based interventions. Understanding the current climate of laypersons’ willingness and readiness to respond to emergencies is crucial in this new context.

- Timeliness with the HEARTS Act: This investigation is particularly timely in light of the recent passage of the HEARTS (Health Education, Awareness, Research, and Training in Schools) Act, which mandates schools to create cardiac emergency response plans, offer CPR and AED training, and ensure the accessibility of AEDs. One-quarter of this study’s participants were high school students whose voices are critical in shaping early training initiatives. As highlighted in the conclusion, “Early and continuous training, starting with middle and high school students, could help build a culture of action and prepare future laypersons to act promptly in cardiac emergencies”.

4.5. Limitations and Future Research and Interventions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Community Development–Resuscitation Education, AED, and CPR Training (CD-REACT) Trainer Guide

- Education (15 min)

- Introduce yourself to the audience and share what skills the audience will learn today.

- ○

- If AV is available, we will play the American Heart Association’s CPR in Action video.

- ○

- Ask the audience: What is cardiac arrest vs. heart attack? Do you have experience with giving CPR?

- ○

- Top lines: Hands-Only CPR can triple the chance of survival. Chain of survival: identify cardiac arrest, call 911, start CPR, and administer an Automatic External Defibrillator (AED), if available, while you wait for paramedics. Goal: keep the brain alive; CPR pumps blood to the brain when the heart cannot.

- Demonstration I: Hands-Only CPR (15 min)

- Set the scene: You see a person pass out in a grocery store. Ask the audience: What do you do first?

- ○

- Confirm unresponsiveness: Ask the person loudly, “Are you okay?”- NO RESPONSE

- ○

- Check the breathing: if there is any abnormality in the breathing pattern → Call 911

- ○

- Do not attempt to check the pulse to confirm—it is unreliable; you could be feeling your own pulse.

- Demonstrate CPR and emphasize important elements:

- ○

- Place your dominant hand on top of the non-dominant hand touching the chest and interlock fingers.

- ○

- Find the area just below the center of the chest above the diaphragm. Keep your elbows locked and bend forward so your body weight can help you with compressions

- ○

- 100 compressions per minute, two inches deep, allow the chest to come back to its normal state, uninterrupted for two minutes

- ○

- NO more mouth-to-mouth breathing (not beneficial in adults). Avoid all CPR interruptions. The AHA still recommends CPR with compressions and breaths for infants, children, victims of drowning or drug overdose, and people who collapse due to breathing problems.

- Hands-on Skills Practice (set to music) (20 min): Participants practice on their take-home CPR manikins, and the training team circles the room to help with form and answer questions. The manikins make a clicking noise when CPR is administered correctly.

- Demonstration II: AED use (10 min): Return to the front of the room.

- Ask the audience: Where can you find an AED? Airports, schools, restaurants, libraries, gyms. Do you know where an AED is in your workplace/school? If I open this device right now, will it shock me?

- Ask a volunteer to come to the front and demonstrate AED use: place pads, provide shock, and resume CPR.

- Call for a volunteer to run the ‘Chain of Survival’ (described above) and conclude (5 min).

- ○

- What if I break someone’s ribs? Broken ribs can be repaired. You are saving a life.

- ○

- Can you be sued for giving CPR to a stranger? No, NYS Good Samaritan Law protects you.

- ○

- Is this training official CPR certification? No, but you will receive a Certificate of Completion.

Appendix B. Community Development Resuscitation Education and CPR/AED Training (CD-REACT)

| Consent: I agree to participate in this anonymous and voluntary survey. I grant permission for the data to be used for informational purposes. | |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

References

- Moon, S.; Bobrow, B.J.; Vadeboncoeur, T.F.; Kortuem, W.; Kisakye, M.; Sasson, C.; Stolz, U.; Spaite, D.W. Disparities in bystander CPR provision and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest according to neighborhood ethnicity. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 32, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starks, M.A.; Schmicker, R.H.; Peterson, E.D.; May, S.; Buick, J.E.; Kudenchuk, P.J.; Drennan, I.R.; Herren, H.; Jasti, J.; Sayre, M.; et al. Association of neighborhood demographics with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest treatment and outcomes: Where You Live May Matter. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, G.; Gallagher, E.J.; Paul, P. Outcome of out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in New York City. JAMA 1994, 271, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfal, R.E.; Reissman, S.; Doering, G. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: An 8-year New York City experience. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1996, 14, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Gibbs, B.B.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; et al. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e347–e913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.S.; Girotra, S.; Tang, Y.; Al-Araji, R.; Nallamothu, B.K.; McNally, B. Outcomes for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the United States During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, C.; Rogers, M.A.; Dahl, J.; Kellermann, A.L. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010, 3, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.S.; Merritt, R.; McNally, B.; Chang, A.; Al-Araji, R.; Mawani, M.; Ahn, K.O.; Girotra, S. Bystander CPR and Long-Term Survival in Older Adults With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JACC Adv. 2023, 2, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, J.; Thode, H.; Stapleton, E.; Singer, A.J. Current knowledge of and willingness to perform Hands-Only™ CPR in laypersons. Resuscitation 2013, 84, 1574–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellano, K.; Crouch, M.P.H.; Rajdev, M.B.A.; McNally, M.P.H. Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) Report on the Public Health Burden of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Available online: https://mycares.net/sitepages/uploads/2024/2023_flipbook/index.html?page=1 (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Dainty, K.N.; Colquitt, B.; Bhanji, F.; Hunt, E.A.; Jefkins, T.; Leary, M.; Ornato, J.P.; Swor, R.A.; Panchal, A. Understanding the Importance of the Lay Responder Experience in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, E852–E867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.L.; Shahidah, N.; Saffari, S.E.; Ng, Q.X.; Ho, A.F.W.; Leong, B.S.-H.; Arulanandam, S.; Siddiqui, F.J.; Ong, M.E.H. Impact of COVID-19 on Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, C.; Magid, D.J.; Chan, P.; Root, E.D.; McNally, B.F.; Kellermann, A.L.; Haukoos, J.S. Association of Neighborhood Characteristics with Bystander-Initiated CPR. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasson, C.; Haukoos, J.S.; Bond, C.; Rabe, M.; Colbert, S.H.; King, R.; Sayre, M.; Heisler, M. Barriers and Facilitators to Learning and Performing Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Neighborhoods With Low Bystander Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Prevalence and High Rates of Cardiac Arrest in Columbus, OH. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2013, 6, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, C.; Haukoos, J.S.; Ben-Youssef, L.; Ramirez, L.; Bull, S.; Eigel, B.; Magid, D.J.; Padilla, R. Barriers to Calling 911 and Learning and Performing Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation for Residents of Primarily Latino, High-Risk Neighborhoods in Denver, Colorado. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2015, 65, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinier, K.; Thomas, E.; Andrusiek, D.L.; Aufderheide, T.P.; Brooks, S.C.; Callaway, C.W.; Pepe, P.E.; Rea, T.D.; Schmicker, R.H.; Vaillancourt, C.; et al. Socioeconomic status and incidence of sudden cardiac arrest. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, 1705–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foraker, R.E.; Rose, K.M.; Kucharska-Newton, A.M.; Ni, H.; Suchindran, C.M.; Whitsel, E.A. Variation in rates of fatal coronary heart disease by neighborhood socioeconomic status: The atherosclerosis risk in communities surveillance (1992–2002). Ann. Epidemiol. 2011, 21, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.S.; Girotra, S.; Blewer, A.; Kennedy, K.F.; McNally, B.F.; Benoit, J.L.; Starks, M.A. Race and Sex Differences in the Association of Bystander CPR for Cardiac Arrest. Circulation 2024, 150, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, R.A.; Girotra, S.; McNally, B.F.; Breathett, K.; Del Rios, M.; Kennedy, K.F.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Sasson, C.; Chan, P.S.; CARES Surveillance Group. Racial And Ethnic Differences in Bystander Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation For Witnessed Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 15, A22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.L.; Cox, M.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Nichol, G.; Thomas, K.L.; Chan, P.S.; Saha-Chaudhuri, P.; Fosbol, E.L.; Eigel, B.; Clendenen, B.; et al. Rates of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipsma, K.; Stubbs, B.A.; Plorde, M. Training rates and willingness to perform CPR in King County, Washington: A community survey. Resuscitation 2011, 82, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.; Heisler, M.; Sayre, M.R.; Colbert, S.H.; Bond-Zielinski, C.; Rabe, M.; Eigel, B.; Sasson, C. Identification of Factors Integral to Designing Community-based CPR Interventions for High-risk Neighborhood Residents. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2015, 19, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Winter, M.K.; Mossesso, V.N., Jr. Bystander CPR in Two Predominantly African American Communities. Adv. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2000, 22, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R.A.; Spertus, J.A.; Girotra, S.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Kennedy, K.F.; McNally, B.F.; Breathett, K.; Del Rios, M.; Sasson, C.; Chan, P.S. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Bystander CPR for Witnessed Cardiac Arrest. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swor, R.; Khan, I.; Domeier, R.; Honeycutt, L.; Chu, K.; Compton, S. CPR training and CPR performance: Do CPR-trained bystanders perform CPR? Acad Emerg. Med. 2006, 13, 596–601. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, T.C.; Clark, M.J.; Dingle, G.A.; FitzGerald, G. Factors influencing Queenslanders’ willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2003, 56, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coons, S.J.; Guy, M.C. Performing bystander CPR for sudden cardiac arrest: Behavioral intentions among the general adult population in Arizona. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta Hansen, C.; Rosenkranz, S.M.; Folke, F.; Zinckernagel, L.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Sondergaard, K.B.; Nichol, G.; Hulvej Rod, M. Lay Bystanders’ Perspectives on What Facilitates Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Use of Automated External Defibrillators in Real Cardiac Arrests. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbie, F.; Uny, I.; Eadie, D.; Duncan, E.; Stead, M.; Bauld, L.; Angus, K.; Hassled, L.; MacInnes, L.; Clegg, G. Barriers to bystander CPR in deprived communities: Findings from a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233675. [Google Scholar]

- Blewer, A.L.; McGovern, S.K.; Schmicker, R.H.; May, S.; Morrison, L.J.; Aufderheide, T.P.; Daya, M.; Idris, A.H.; Callaway, C.W.; Kudenchuk, P.J.; et al. Gender Disparities Among Adult Recipients of Bystander Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in the Public. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 11, e004710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perman, S.M.; Shelton, S.K.; Knoepke, C.; Rappaport, K.; Matlock, D.D.; Adelgais, K.; Havranek, E.P.; Daugherty, S.L. Public Perceptions on Why Women Receive Less Bystander Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Than Men in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Circulation 2019, 139, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, S.K.; Rice, J.D.; Knoepke, C.E.; Matlock, D.D.; Havranek, E.P.; Daugherty, S.L.; Perman, S.M. Examining the Impact of Layperson Rescuer Gender on the Receipt of Bystander CPR for Women in Cardiac Arrest. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 17, e010249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uny, I.; Angus, K.; Duncan, E.; Dobbie, F. Barriers and facilitators to delivering bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in deprived communities: A systematic review. Perspect. Public Health 2023, 143, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, K.M.; McIsaac, S.M.; Ohle, R. Impact of community-based interventions on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fratta, K.A.; Bouland, A.J.; Vesselinov, R.; Levy, M.J.; Seaman, K.G.; Lawner, B.J.; Hirshon, J.M. Evaluating barriers to community CPR education. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, C. CUIMC and NYP Join Hands with AHA to Bring Lifesaving Skills to Northern Manhattan Community. Available online: https://www.acp.cuimc.columbia.edu/news/cuimc-and-nyp-join-hands-aha-train-northern-manhattan-community-lifesaving-skills (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Kind, A.J.; Buckingham, W.R. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible—The Neighborhood Atlas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2456–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpati, A.; Lu, X.; Mostashari, F.; Thorpe, L.; Frieden, T.R. The Health of Inwood and Washington Heights. N. Y. City Community Health Profiles 2003, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Conditions Data: Neighborhood Poverty. Available online: https://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/data-explorer/economic-conditions/?id=103#display=summary (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Abdulhay, N.M.; Totolos, K.; McGovern, S.; Hewitt, N.; Bhardwaj, A.; Buckler, D.G.; Leary, M.; Abella, B.S. Socioeconomic disparities in layperson CPR training within a large U.S. city. Resuscitation 2019, 141, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, Å.; Thorén, A.; Holmberg, S.; Herlitz, J. Attitudes of trained Swedish lay rescuers toward CPR performance in an emergency. A survey of 1012 recently trained CPR rescuers. Resuscitation 2000, 44, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, N.T.; Kumar, S.L.; Bhandari, R.K.; Kumar, S.D. Disparities in Survival with Bystander CPR following Cardiopulmonary Arrest Based on Neighborhood Characteristics. Emerg. Med. Int. 2016, 2016, 6983750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State, NY. 2021. Available online: https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/general/opioid_overdose_prevention/good_samaritan_law.htm (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Congress US. Cardiac Arrest Survival Act of 2000. 2000. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/106th-congress/house-report/634/1 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Benson, P.C.; Eckstein, M.; McClung, C.D.; Henderson, S.O. Racial/ethnic differences in bystander CPR in Los Angeles, California. Ethn. Dis. 2009, 19, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dobbie, F.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Clegg, G.; Stirzaker, R.; Bauld, L. Attitudes towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Results from a cross-sectional general population survey. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blewer, A.L.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Leary, M.; Dutwin, D.; McNally, B.; Anderson, M.L.; Morrison, L.J.; Aufderheide, T.P.; Daya, M.; Idris, A.H.; et al. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Training Disparities in the United States. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaramuzzo, L.A.; Yuk Wong, R.N.; Gordils-Perez, J. Cardiopulmonary arrest in the outpatient setting: Enhancing patient safety through rapid response algorithms and simulation teaching. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudenchuk, P.J.; Stuart, R.; Husain, S.; Fahrenbruch, C.; Eisenberg, M. Treatment and outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in outpatient health care facilities. Resuscitation 2015, 97, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.M.; Isbye, D.L.; Lippert, F.K.; Rasmussen, L.S. Can mass education and a television campaign change the attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a rural community? Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2013, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce, N.A. Centering Health Equity in Population Health Surveys. JAMA Health Forum. 2020, 1, e201429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau USC. American Community Survey 1-year Estimates. Retrieved from Census Reporter Profile page for NYC-Manhattan Community District 12—Washington Heights & Inwood PUMA, NY. 2022. Available online: https://censusreporter.org/profiles/79500US3604112-nyc-manhattan-community-district-12-washington-heights-inwood-puma-ny/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Cave, D.M.; Aufderheide, T.P.; Beeson, J.; Ellison, A.; Gregory, A.; Hazinski, M.F.; Hiratzka, L.F.; Lurie, K.G.; Morrison, L.J.; Mosesso, V.N.; et al. Importance and implementation of training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillation in schools: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011, 123, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants Characteristics (N = 669) | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 26 (170) 33 (216) 23 (157) 16 (103) 2 (16) |

| Sex | |

| 31 (206) 67 (445) 1 (4) 1 (5) |

| Race | |

| 5 (34) |

| 12 (77) |

| 24 (163) |

| 56 (373) |

| 3 (22) |

| Ethnicity | |

| 64 (426) |

| 32 (217) |

| 4 (26) |

| Education Status | |

| 29 (188) |

| 66 (425) |

| 5 (30) |

| Occupational Status | |

| 41 (270) |

| 16 (106) |

| 27 (175) |

| 1 (10) |

| 15 (97) |

| Have you ever learned CPR before? | |

| 35 (230) |

| 62 (409) |

| 3 (22) |

| Is Cardiac Arrest the same as a Heart Attack? | |

| 22 (146) 45 (292) 33 (212) |

| Have you ever learned how to administer an AED? | |

| 17 (117) 77 (504) 6 (37) |

| Do you know if there is an AED in the building where you work or study? | |

| 22 (136) 16 (102) 62 (386) |

| Concerns | Low-Resource Communities (N = 632) | Hispanic (N = 402) | Non-Hispanic Black (N = 72) | Non-Hispanic White (N = 80) | p-Value | High-Resource Communities (N = 292) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||

| Performing CPR incorrectly | 67 (423) | 64 (256) | 79 (57) | 64 (51) | 0.03 | 63 (184) | 0.3 |

| Fear of harming the victim | 56 (353) | 49 (198) | 75 (54) | 61 (49) | <0.01 | --- | |

| Afraid of being sued if the person dies | 53 (336) | 53 (211) | 61 (44) | 55 (44) | 0.4 | 47 (137) | 0.2 |

| Catching a disease | 30 (212) | 30 (120) | 49 (35) | 44 (35) | 0.01 | 32 (92) | 0.7 |

| Being wrongfully accused of sexual harassment | 24 (153) | 23 (93) | 17 (12) | 23 (18) | 0.5 | --- | |

| Somebody else would do it better | 29 (184) | 23 (94) | 51 (37) | 28 (22) | <0.01 | 23 (67) | 0.3 |

| Hurting myself while I provide CPR | 13 (82) | 12 (50) | 15 (11) | 14 (11) | 0.7 | 12 (35) | 0.9 |

| Other | 6 (37) | 7 (30) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.06 | 3 (8) | 0.7 |

| Willingness Factors | Low-Resource Communities (N = 590) | Hispanic (N = 369) | Non-Hispanic Black (N = 68) | Non-Hispanic White (N = 76) | p-Value | High-Resource Communities) (N = 243) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||||

| Knowing the person, other than family | 67 (398) | 63 (233) | 82 (56) | 70 (53) | <0.01 | 48 (116) | <0.01 |

| Family member | 55 (325) | 56 (205) | 57 (39) | 54 (41) | 0.9 | 39 (95) | <0.01 |

| Medical professional | 34 (198) | 30 (111) | 41 (28) | 39 (30) | 0.08 | 39 (95) | 0.4 |

| Age of patient | 34 (203) | 35 (130) | 32 (22) | 33 (25) | 0.8 | 21 (51) | 0.07 |

| The responder has a physical disability | 25 (147) | 24 (89) | 23 (16) | 26 (20) | 0.8 | 19 (45) | 0.4 |

| Gender of patient | 20 (120) | 21 (76) | 16 (11) | 20 (15) | 0.7 | 10 (24) | 0.2 |

| Race/ethnicity of patient | 14 (81) | 12 (46) | 22 (15) | 7 (5) | 0.03 | 8 (19) | 0.5 |

| Other | 8 (46) | 8 (28) | 3 (2) | 9 (7) | 0.3 | 19 (47) | 0.1 |

| Barriers. | Low-Resource Communities (N = 635) | Hispanic (N = 408) | Non-Hispanic Black (N = 66) | Non-Hispanic White (N = 80) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Don’t know how to use | 66 (417) | 67 (273) | 59 (39) | 64 (51) | 0.6 |

| Will harm the other person | 25 (158) | 22 (90) | 41 (27) | 25 (20) | <0.01 |

| Difficult to Use | 17 (108) | 13 (55) | 29 (19) | 20 (16) | <0.01 |

| Think I am not allowed to use | 15 (94) | 14 (59) | 28 (19) | 8 (6) | <0.01 |

| Will not help the person | 4 (26) | 4 (16) | 9 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.06 |

| Concerns | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | * Multivariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performing CPR incorrectly | ||||

| Reference 2.2 (1.0–4.4) 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.03 0.9 | Reference 2.5 (1.2–5.2) 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 0.02 0.9 |

| Fear of harming the victim | ||||

| Reference 1.9 (0.9–3.8) 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.07 0.05 | Reference 2.0 (0.9–4.1) 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.06 0.01 |

| Afraid of being sued if the person dies | ||||

| Reference 1.3 (0.7–2.4) 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.4 0.7 | Reference 0.9 (0.5–1.5) 1.2 (0.6–2.3) | 0.7 0.6 |

| Catching a disease | ||||

| Reference 1.2 (0.6–2.3) 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.5 0.02 | Reference 1.1 (0.6–2.2) 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.7 0.07 |

| Being wrongfully accused of sexual harassment | ||||

| Reference 0.7 (0.3–1.6) 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | 0.4 0.9 | Reference 0.7 (0.3–1.5) 1.0 (0.5–1.8) | 0.3 0.9 |

| Somebody else would do it better | ||||

| Reference 2.8 (1.4–5.4) 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | <0.01 0.4 | Reference 3.2 (1.6–6.5) 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | <0.01 0.5 |

| Hurting myself while I provide CPR | ||||

| Reference 1.1 (0.5–2.8) 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | 0.8 0.7 | Reference 0.9 (0.4–1.8) 0.9 (0.4–2.4) | 0.8 0.9 |

| Other | ||||

| Reference 0.5 (0.1–6.1) 3.1 (0.7–13.4) | 0.6 0.1 | Reference 0.5 (0.0–5.2) 3.8 (0.9–16.5) | 0.5 0.07 |

| Concerns | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | * Multivariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowing the person, other than family | ||||

| Reference 2.0 (0.9–4.5) 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.08 0.3 | Reference 2.3 (1.0–5.3) 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.04 0.5 |

| Family member | ||||

| Reference 1.1 (0.6–2.2) 1.1 (0.6–1.7) | 0.7 0.8 | Reference 1.2 (0.6–2.3) 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.6 0.7 |

| Medical professional | ||||

| Reference 1.1 (0.6–2.1) 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.8 0.1 | Reference 1.3 (0.6–2.5) 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.5 0.1 |

| Age of patient | ||||

| Reference 1.0 (0.5–1.9) 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.9 0.7 | Reference 1.0 (0.4–1.9) 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 0.8 0.5 |

| The responder has a physical disability | ||||

| Reference 0.9 (0.5–1.5) 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | 0.7 0.7 | Reference 1.0 (0.5–1.7) 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 0.9 0.7 |

| Gender of patient | ||||

| Reference 0.8 (0.3–1.8) 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.6 0.8 | Reference 0.8 (0.3–1.8) 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.5 0.8 |

| Race/ethnicity of patient | ||||

| Reference 3.6 (1.3–10.5) 1.8 (0.7–4.7) | 0.02 0.2 | Reference 3.7 (1.2–10.8) 1.9 (0.7–5.3) | 0.02 0.2 |

| Other | ||||

| Reference 0.3 (0.1–1.4) 0.8 (0.3–1.9) | 0.1 0.6 | Reference 0.3 (0.1–1.6) 0.8 (0.3–2.0) | 0.2 0.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirsch, C.; Sachdeva, B.; Roca-Dominguez, D.; Foster, J.; Bryant, K.; Gautier-Matos, N.; Minguez, M.; Williams, O.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Homma, S.; et al. Assessing Attitudes and Perceptions of High-Risk, Low-Resource Communities Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Public-Access Defibrillation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020537

Hirsch C, Sachdeva B, Roca-Dominguez D, Foster J, Bryant K, Gautier-Matos N, Minguez M, Williams O, Elkind MSV, Homma S, et al. Assessing Attitudes and Perceptions of High-Risk, Low-Resource Communities Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Public-Access Defibrillation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):537. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020537

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirsch, Carolyn, Bhanvi Sachdeva, Dilenny Roca-Dominguez, Jordan Foster, Kellie Bryant, Nancy Gautier-Matos, Mara Minguez, Olajide Williams, Mitchell S. V. Elkind, Shunichi Homma, and et al. 2025. "Assessing Attitudes and Perceptions of High-Risk, Low-Resource Communities Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Public-Access Defibrillation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020537

APA StyleHirsch, C., Sachdeva, B., Roca-Dominguez, D., Foster, J., Bryant, K., Gautier-Matos, N., Minguez, M., Williams, O., Elkind, M. S. V., Homma, S., Lantigua, R., & Agarwal, S. (2025). Assessing Attitudes and Perceptions of High-Risk, Low-Resource Communities Towards Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Public-Access Defibrillation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020537