Abstract

Background: Mental health issues can significantly affect the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of adults suffering from hyperlipidemia. Therefore, in this study, the aim was to examine how depression and anxiety are related to the HRQoL of adults with hyperlipidemia. Methods: Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey for 2016 through 2022 were used to identify adult patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia aged 18 or older. The RAND-12 Physical and Mental Component Summary (PCS and MCS) was used to determine HRQoL. After considering variables such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities, linear regression was used to investigate the relationship between anxiety, depression, and HRQoL in individuals with hyperlipidemia. Results: A sample of 7984 adults with hyperlipidemia was identified; 9.0% experienced depression, 10.2% had anxiety, and 6.8% had both disorders. The HRQoL mean scores were lowest for adults with depression and anxiety compared to those with hyperlipidemia only. Results from the adjusted linear regression analysis revealed that hyperlipidemia patients with depression (MCS: β = −5.535, p-value < 0.0001), anxiety (MCS: β = −4.406, p-value < 0.0001), and both depression and anxiety (MCS: β = −8.730, p-value < 0.0001) had a significantly lower HRQoL compared to patients with hyperlipidemia only. However, in this study, it was also found that those who were physically active and employed had notably higher scores on the PCS and MCS than those who were not. Conclusions: The links between anxiety, depression, and lower HRQoL in patients with hyperlipidemia are clarified in this nationally representative study. This research also revealed the adverse effects of coexisting chronic conditions on HRQoL while emphasizing the benefits of employment and regular exercise. Importantly, these findings provide a compelling case for enhancing healthcare planning, allocating resources, and promoting lifestyle changes in adults with hyperlipidemia, underlining the importance of addressing mental health issues in this population.

1. Introduction

Health-related quality of life is an important outcome measure for individuals with chronic illnesses such as hyperlipidemia. It encompasses all the various dimensions of an individual’s physical, mental, and social well-being [1]. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) can be negatively impacted by hyperlipidemia and other chronic illnesses. Hyperlipidemia is a group of inherited and acquired conditions that are characterized by an elevated level of lipids (fats) in the blood, which includes cholesterol, triglycerides, or both [2]. Hyperlipidemia can be divided into the two categories of a genetic condition known as primary hyperlipidemia that can result from abnormalities in a number of proteins that are involved in lipid transport or metabolism [3], and a secondary hyperlipidemia that can result from changes in lipid metabolism brought on by a variety of illnesses or factors, including endocrine disorders (like diabetes mellitus), liver diseases (like cirrhosis), renal diseases (like nephrotic syndrome), dietary factors (like a high-fat diet), or medications (like corticosteroids).

It is usually a chronic, progressive illness that requires dietary and lifestyle modifications as well as that it might be necessary for additional lipid-lowering drugs. Around 12% of adults in the United States (US) have hyperlipidemia in general [4]. It is estimated that less than 35% of those individuals effectively manage their hyperlipidemia, indicating an illness not receiving enough treatment [2]. Untreated or undertreated hyperlipidemia can lead to many forms of vascular diseases, such as peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular accidents, type II diabetes, and hypertension [2]. The consequences of hyperlipidemia on a person’s health can be significant and financially burdensome [5,6]. Hyperlipidemia was one of the ten most costly medical conditions in the US adult population in 2008 [7]. It can significantly impact people’s psychological well-being; individuals with hyperlipidemia are at high risk of depression, according to epidemiological studies that found a bi-directional relationship between hyperlipidemia and depression [8,9,10]. In addition, hyperlipidemia is significantly related to HRQoL which in turn is related to the hyperlipidemia patients’ health outcomes.

Therefore, maintaining a high HRQoL in the face of the problems caused by hyperlipidemia may be one of the main goals for adults with hyperlipidemia. This could be achieved by lipid control, adherence to medications, and examining the psychological health of adults with hyperlipidemia. For example, evidence from a study comparing the HRQoL of individuals who experience different levels of lipid control supports that controlled lipid profiles were positively related to HRQOL [11,12]. In addition, medication adherence was found to be independently correlated with a high HRQoL score in hyperlipidemia [13,14]. However, depression had a significantly lower HRQoL as evidenced by a study in China among 10,115 hyperlipidemia patients [15]. There are few studies that have looked at the relationship between depression, anxiety, and HRQoL in adults with hyperlipidemia [15]. Therefore, understanding the causes underlying a lower HRQoL is essential, especially when considering mental health. We hypothesized that anxiety and depression are associated with lower HRQoL in adults with hyperlipidemia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data

A retrospective longitudinal study design was used. Data were retrieved from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) for 2016 to 2022. MEPS is a nationwide survey that gathers information from United States (US) citizens on demographics, socioeconomic status, insurance, medical conditions, medication usage, healthcare utilization, cost, etc.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In this study, adults were included aged between 18 and 64 years old who were diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. Adults must have no missing data on HRQoL and be alive within the study years. To identify adults with hyperlipidemia from MEPS data, we used the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) clinical diagnosis codes (E78) from the MEPS Medical Condition File data [16]. We excluded adults with missing data on HRQoL and those without a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Outcome: Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

MEPS evaluated the HRQoL using the Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey (VR-12©) [17]. It is a self-administered health survey composed of 12 items that evaluate 8 health domains, including physical and mental health [18]. It has been categorized into the two domains of the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS). It is a widely used, recognized reliable and validated patient-reported outcome measure, with an internal-consistency reliability of 0.94 for physical functioning and 0.89 for mental functioning [17,19,20,21]. The VR-12 instrument uses five-point ordinal response choices of “no, none of the time”, “yes, a little of the time”, “yes, some of the time”, “yes, most of the time”, and “yes, all of the time”.

2.3.2. Independent Variables

Adults with hyperlipidemia were categorized into the following four mutually exclusive groups: hyperlipidemia only, hyperlipidemia and anxiety, hyperlipidemia and depression, hyperlipidemia and both diseases. We used the ICD-10-CM clinical diagnosis codes from MEPS to identify individuals with depression (‘F34’, ‘F39’, ‘F32’) and anxiety (‘F40’, ‘F41’).

Other independent variables that were evaluated included demographics and socioeconomic variables (gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, region of residency, education level, employment status, and poverty status), health insurance and medication insurance, perceived physical health, coexisting chronic health conditions, and physical activity.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics, including mean, standard deviation, frequencies, and percentages were reported using descriptive statistics. Differences in individual characteristics by hyperlipidemia groups were evaluated using chi-square tests. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess that the data were normally distributed before conducting the parametric tests. The variances in HRQoL means between hyperlipidemia groups were determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons to identify which specific groups differed. A multivariable linear regression model was used to evaluate the link between hyperlipidemia groups and HRQoL after adjusting for other independent variables. We considered the complicated survey design of the MEPS in the analysis by adding variance adjustment weights (strata and primary sample unit) from the MEPS with person-level weights. All statistical analysis used the Statistical Analysis System, SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

The study sample was composed of 7984 adults with hyperlipidemia; the majority of the study sample were women (55.6%), aged 50 to 64 (75.2%), white (68.4%), and had education higher than high school (89.9%). About 9.0% of adults with hyperlipidemia also experienced depression, 10.2% had anxiety, and 6.8% had both disorders (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample (n = 7984), number, and row percentage of characteristics by hyperlipidemia (HLD) groups.

Women with hyperlipidemia had a significantly higher rates of depression (13.4% vs. 6.0%), anxiety (13.9% vs. 7.3%), and comorbid anxiety and depression (9.7% vs. 4.4%, p-value ≤ 0.0001) when compared to men. Furthermore, unemployed hyperlipidemia patients had significantly higher rates of depression (14.3% vs. 9.6%) and comorbid anxiety and depression (11.7% vs. 4.4%, p-value < 0.0001) than employed hyperlipidemia patients. Additionally, significantly higher rates of comorbid depression and anxiety were identified among hyperlipidemia adults with heart disease, diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) than those without these comorbidities (p-value < 0.0001).

3.2. Health-Related Quality of Life by Hyperlipidemia Groups

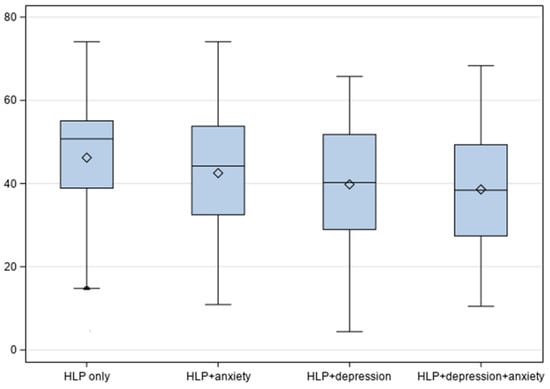

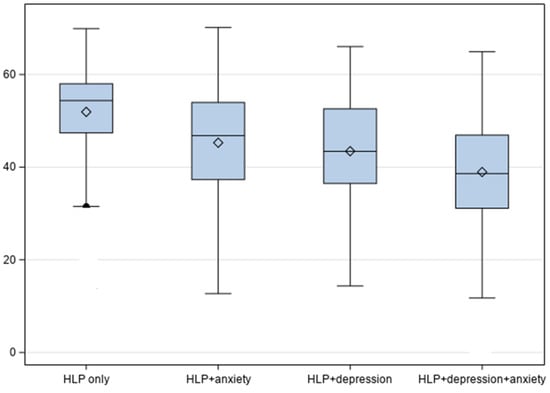

There were significant differences in the PCS and MCS mean scores between hyperlipidemia groups (Table 2, Figure 1 and Figure 2). For example, compared to other groups, adults with both depression and anxiety had a significantly lower mean PCS score (mean = 40.19, SE = 0.63) and lower mean MCS score (mean = 40.13, SE = 0.62).

Table 2.

Health-related quality of life weighted means scores by hyperlipidemia groups.

Figure 1.

HRQoL Physical Component Summary scores by hyperlipidemic groups.

Figure 2.

HRQoL Mental Component Summary scores by hyperlipidemic groups.

Mean difference comparison between different hyperlipidemia groups was performed by using the ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons (Table 3), which revealed the following:

Table 3.

Post hoc analysis of the mean difference in health-related quality of life between hyperlipidemia groups.

Patients with only hyperlipidemia have a significant higher mean PCS and MCS scores as compared to the other groups (hyperlipidemia and depression, and hyperlipidemia and anxiety, hyperlipidemia and depression and anxiety).

3.3. Adjusted Linear Regression Analysis for Health-Related Quality of Life

The adjusted relationship between hyperlipidemia groups and HRQoL is displayed in Table 4. After adjusting for all confounding variables, hyperlipidemia patients with depression (MCS: β = −5.535, p-value < 0.0001), anxiety (MCS: β = −4.406, p-value < 0.0001), and both depression and anxiety (MCS: β = −8.730, p-value < 0.0001) had a significantly lower HRQoL than those with hyperlipidemia only.

Table 4.

Adjusted multivariable linear regressions on HRQoL.

Factors positively associated with HRQoL included employment, perceived general health, and physical activity. For example, adults who perceived their physical health to be excellent or very good have a higher HRQoL in both physical health summary score (PCS: β = 11.709, p-value < 0.0001) and mental health summary score (MCS: β = 6.290, p-value < 0.0001) compared to those who perceived their health to be poor.

Comorbidities were negatively associated with both PCS and MCS; individuals with heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, osteoarthritis, and GERD have a lower HRQoL in both physical and mental health summary scores than those without those comorbidities p-value < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

The results presented in this research provide an insight into the negative relationship between comorbid depression and anxiety and HRQoL in a nationally representative sample of US adults with hyperlipidemia. Four hyperlipidemia groups were compared, as follows: hyperlipidemia only, hyperlipidemia and depression, hyperlipidemia and anxiety, and hyperlipidemia with both depression and anxiety. In terms of mental comorbidities, in this study it was revealed that women with hyperlipidemia had significantly higher rates of depression, anxiety, and comorbid conditions compared to men, which is in line with earlier studies [22] highlighting the potential gender disparity in mental health conditions among hyperlipidemia patients, warranting further investigation into hormonal, psychological, or societal factors contributing to this finding. In fact, gender differences exist not only in mental health but also in clinical medicine, treatment, epidemiology, symptoms, and health outcomes, as evident in above 10,000 published research [23]. Another important finding was that unemployed individuals showed higher rates of depression and comorbid conditions than their employed counterparts. Further, higher rates of anxiety and depression were seen in hyperlipidemic adults with comorbidities (i.e., heart disease, diabetes, asthma, COPD, and GERD); this underscores the bidirectional relationship between physical and mental health, emphasizing the need for integrated care.

In terms of quality of life, our findings highlight the significant impact of depression and anxiety on QoL in individuals with hyperlipidemia by affecting both physical and mental well-being. These results are consistent with a previous study, which has shown that in adults with dyslipidemia, mental health diminishes the overall QoL [15]. Several pathophysiological mechanisms in hyperlipidemia may lead to these mental conditions [9,24,25,26,27]. First, inflammation and oxidative stress induced by high cholesterol levels, which affect brain function and neurotransmitter activity, potentially lead to depression and anxiety; this inflammatory pathway is supported by numerous studies that have linked chronic inflammation to both the onset and progression of depression [25,26,27]. Secondly, cardiovascular risks associated with hyperlipidemia, where fear of events or complications can induce chronic stress and worsen depression and anxiety [27]. Finally, physical limitations, such as those caused by atherosclerosis, which can cause disabilities and fatigue, further contributing to a negative outlook and exacerbating mental health symptoms [9]. The strong link between mental health disorders and reduced HRQoL in hyperlipidemia patients underscores the importance of addressing psychological conditions alongside physical health.

Further, hyperlipidemic adults with chronic comorbidities such as heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, asthma, and GERD have significantly reduced HRQoL. In our study sample, approximately two-thirds of adults with hyperlipidemia had hypertension, and one-third had diabetes. The presence of these conditions increases the risk of cardiovascular events and negatively impacts quality of life. Diabetes can lead to complications such as neuropathy and kidney issues, further affecting overall health. Together, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia significantly worsen cardiovascular health and contribute to a decline in health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Implementing lifestyle changes, including improvements in diet and exercise, is crucial for managing these conditions. A study in China among 9339 subjects with dyslipidemia reported that a higher healthy lifestyle score (HLS) was based on the following factors: smoking, alcohol drinking, diet, body mass index, and physical activity was linked to a lower risk of hypertension and diabetes, emphasizing the importance of preventative strategies [28]. In addition, exploring the relationship between these comorbidities and HRQoL is vital for improving patient care, and future research should focus on how interventions targeting hypertension and diabetes impact HRQoL in hyperlipidemic patients.

Furthermore, employment, good perceived general health, and physical activity were positively associated with HRQoL; these findings suggest that interventions promoting physical activity and employment could enhance HRQoL. Employment might serve as a protective factor due to better financial security, access to healthcare, and social engagement. The association between employment status and quality of life among adults was investigated using the Korea Health Panel survey data [29]. Exercise has been shown to lower depression and anxiety and it is hypothesized that these mood enhancements result from exercise’s effects on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the increase in blood flow to the brain [30]. Additionally, exercise is associated with better cardiovascular health and lower cholesterol levels [30,31]. Therefore, tailored interventions targeting at-risk groups (e.g., unemployed individuals, those with comorbidities, and those who are physically inactive) are essential. In addition, enhancing mental health support and integrating it with chronic disease management could improve overall outcomes. Therefore, to effectively manage the complexities of comorbidities, healthcare systems must change to a more integrated and patient-centered approach. Value-based healthcare models, which reward providers based on improvements in HRQoL, can improve patient well-being and reduce healthcare utilization by prioritizing proactive management of hyperlipidemia and comprehensive care [32].

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

A significant emphasis of the earlier research has been the connection between depression and hyperlipidemia. Thus, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between depression and anxiety and HRQoL among adults with hyperlipidemia using a nationally representative sample of adults in the US. In this study, several variables (i.e., confounders) were also measured, including sociodemographic characters, health and medication insurance coverage, perceived health, physical activity, and concurrent comorbidities. In this study, there were certain limitations when interpreting this study’s findings. Hyperlipidemia treatment and the severity of their illness were not adjusted in the analysis, which may have a relationship with HRQoL. In addition, MEPS does not cover information on the severity or type of depression or anxiety, which could impact the HRQoL of adults with hyperlipidemia. Finally, in this study, only adults were included; thus, the findings cannot be generalized to the elderly population.

4.2. Clinical Practice, Policy, Research, and Public Health Implications

The findings from this study can be used to enhance healthcare services and resource allocation at the healthcare providers’ and policymakers’ levels to minimize the negative consequences of depression and anxiety in individuals with hyperlipidemia and improve public health. In addition, in this study, it is suggested that healthcare providers should, therefore, regularly screen and treat depression and anxiety as early treatment can improve HRQoL and other hyperlipidemia health outcomes. The public health implications from this study call for lifestyle changes as physical activity can significantly improve the severity of their illnesses and their HRQoL. Further studies in this area are necessary as there is a substantial unmet need for additional research to determine the impact of these mental illnesses in HRQoL for patients with hyperlipidemia. In addition, other mental HRQoL instruments should be considered for future studies, such as the Recovering Quality of Life-Utility Index (ReQoL), a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) that evaluates the quality of life for people with different mental health conditions [33].

In addition, future studies need to evaluate the quality of life in patients with dyslipidemia without mental health problems, since the quality of life is negatively influenced by mental health.

5. Conclusions

In this study, valuable insights are provided into the multifaceted factors influencing health outcomes in hyperlipidemia, highlighting the need for a holistic and equitable approach to healthcare delivery. Adults with hyperlipidemia have lower HRQoL due to depression and anxiety in this nationally representative study. These psychological sufferings could impact hyperlipidemia health outcomes. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize early diagnosis and the treatment of depression and anxiety. Also, this research found the adverse effects of coexisting chronic conditions on HRQoL while highlighting the benefits of employment and regular exercise on HRQoL. The findings from this study have implications for clinical practice and policy to improve healthcare services and resource allocation. Promoting lifestyle changes, specifically physical activity, is essential at the public health level, as it may improve the HRQoL of adults with hyperlipidemia.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical review or approval because it utilized a publicly accessible secondary database, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) database.

Informed Consent Statement

Due to the fact that this study employed a secondary database, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) database, which is publicly accessible, patient consent was waived for this research.

Data Availability Statement

Researchers can access the publicly accessible dataset used in this study from the MEPS database at this URL: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data_files.jsp (accessed on 12 November 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

HRQoL: health-related quality of life, MCS: mental health component score, PCS: physical health component score.

References

- Karimi, M.; Brazier, J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics 2016, 34, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.F.; Bordoni, B. Hyperlipidemia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, I.H.; Alkareem, Z.A.; Mosa, A.U. Hyperlipidemia: Pathophysiology, causes, complications, and treatment. A review. Karbala J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 1, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, G.; Chen, G.; Luo, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Qian, J. Distribution of lipid levels and prevalence of hyperlipidemia: Data from the NHANES 2007–2018. Lipids Health Dis. 2022, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.M.; Wang, L.; Gandra, S.R.; Quek, R.G.W.; Li, L.; Baser, O. Clinical and economic burden associated with cardiovascular events among patients with hyperlipidemia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, G.; Fang, J.; Mercado, C. Hyperlipidemia and Medical Expenditures by Cardiovascular Disease Status in US Adults. Med. Care 2017, 55, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A. Top 10 Most Costly Conditions Among Men and Women, 2008: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Adult Population, Age 18 and Older. Statistical Brief No. 331, 2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st331/stat331.shtml (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Yazdani, Z.; Jabalameli, S.; Ebrahimi, A.; Raeisi, Z. Relationship between Metabolic Diseases (Diabetes and Hyperlipidemia) with Depression in the Elderly. J. Isfahan Med. Sch. 2022, 40, 647–653. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, C.-S.; Yang, T.-Y.; Muo, C.-H.; Su, H.-L.; Sung, F.-C.; Kao, C.-H. Hyperlipidemia, statin use and the risk of developing depression: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2014, 36, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, I.C.; Lin, C.-H.; Chou, Y.-J.; Chou, P. Increased risk of hyperlipidemia in patients with major depressive disorder: A population-based study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 75, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarab, A.S.; Alefishat, E.A.; Al-Qerem, W.; Mukattash, T.L.; Abu-Zaytoun, L. Variables associated with poor health-related quality of life among patients with dyslipidemia in Jordan. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Gu, H.-Q.; Wang, W.; Ma, L.; Li, W.; on behalf of the CHIEF Research Group. Health-related quality of life in blood pressure control and blood lipid-lowering therapies: Results from the CHIEF randomized controlled trial. Hypertens. Res. 2019, 42, 1561–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantzaras, A.; Yfantopoulos, J. Association between medication adherence and health-related quality of life of patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia. Hormones 2023, 22, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, R.H.; Nagaraju, R.; Prasad, K.; Reddy, S. Assessment of medication adherence and quality of life in hyperlipidemia patients. Int. J. Pharma Bio. Sci. 2012, 1, 388–393. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, G.; Tang, N.; Wu, W. Evaluation of health-related quality of life in adults with and without dyslipidaemia in rural areas of central China. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey HC-231: 2021 Medical Conditions File. [23 November 2024]. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h231/h231doc.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Kazis, L.E.; Selim, A.J.; Rogers, W.; Qian, S.X.; Brazier, J. Monitoring Outcomes for the Medicare Advantage Program: Methods and Application of the VR-12 for Evaluation of Plans. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2012, 35, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey MEPS HC-233. 2021 Full Year. Consolidated Data File. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h233/h233doc.shtml (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Maslak, J.P.; Jenkins, T.J.; Weiner, J.A.; Kannan, A.S.; Patoli, D.M.; McCarthy, M.H.; Hsu, W.K.; Patel, A.A. Burden of Sciatica on US Medicare Recipients. JAAOS—J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2020, 28, e433–e439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.J.; Rothendler, J.A.; Qian, S.X.; Bailey, H.M.; Kazis, L.E. The History and Applications of the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12). J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2022, 45, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazis, L.E.; Rogers, W.H.; Rothendler, J.; Qian, S.; Selim, A.; Edelen, M.O.; Stucky, B.; Rose, A.; Butcher, E. Outcome Performance Measure Development for Persons with Multiple Chronic Conditions; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, C.P.; Asnaani, A.; Litz, B.T.; Hofmann, S.G. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex and gender differences in health. Science & Society Series on Sex and Science. EMBO Rep 2012, 13, 596–603. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, V.; Bhardwaj, A.; Hood, K.; Elias, D.A.; Metcalfe, A.W.S.; Kim, J.S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of lipid metabolomic signatures of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 139, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tao, X.-L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Q.-K.; Li, Z.-J.; Dai, L.; Lei, Y.; Zhu, G.; Wu, Z.-F.; Yang, H.; et al. Association between cardiometabolic index and depression: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2014. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 351, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-W.; Kang, H.-J.; Bae, K.-Y.; Shin, I.-S.; Hong, Y.J.; Ahn, Y.-K.; Jeong, M.H.; Berk, M.; Yoon, J.-S.; Kim, J.-M. Interactions between pro-inflammatory cytokines and statins on depression in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 80, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; Shipley, M.J.; Allan, C.L.; Sexton, C.E.; Jokela, M.; Virtanen, M.; Tiemeier, H.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Singh-Manoux, A. Vascular Risk Status as a Predictor of Later-Life Depressive Symptoms: A Cohort Study. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 72, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Zheng, M.; Duan, X.; Zhou, H.; Huang, J.; Lao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xue, M.; Zhao, W.; et al. Association of healthy lifestyles on the risk of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and their comorbidity among subjects with dyslipidemia. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1006379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, J.-W.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Kwon, Y.D. Gender Difference in Relationship between Health-Related Quality of Life and Work Status. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Madaan, V.; Petty, F.D. Exercise for mental health: Prim Care Companion. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoangelos, K.; Soulis, D.; Soulaidopoulos, S.; Antoniou, C.K.; Tsiori, S.; Papageorgiou, C.; Katsi, V. Health Related Quality of Life and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Behav. Med. 2024, 50, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skou, S.T.; Mair, F.S.; Fortin, M.; Guthrie, B.; Nunes, B.P.; Miranda, J.J.; Boyd, C.M.; Pati, S.; Mtenga, S.; Smith, S.M. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.H.; Keetharuth, A.D.; Wang, L.-L.; Cheung, A.W.-L.; Wong, E.L.-Y. Measuring health-related quality of life and well-being: A head-to-head psychometric comparison of the EQ-5D-5L, ReQoL-UI and ICECAP-A. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).