Construction and Initial Psychometric Validation of the Morana Scale: A Multidimensional Projective Tool Developed Using AI-Generated Illustrations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Unconscious Processes as the Foundation of Projective Diagnostics

1.2. Freud’s Death Drive as a Theoretical Basis for Self-Destructiveness

1.3. Neurobiological Basis of Unconscious Processes

1.4. Suicide Risk Factors

1.4.1. Depression

1.4.2. Aggression

1.4.3. Impulsivity

1.4.4. Anxiety

1.4.5. Psychache (Psychological Pain)

1.4.6. Fantasies About Death

1.5. Protective Factors of Suicide

1.6. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in the Diagnostic Process

1.7. Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Competent Judges Procedure

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Factor Extraction

3.2. Exploratory Analyses

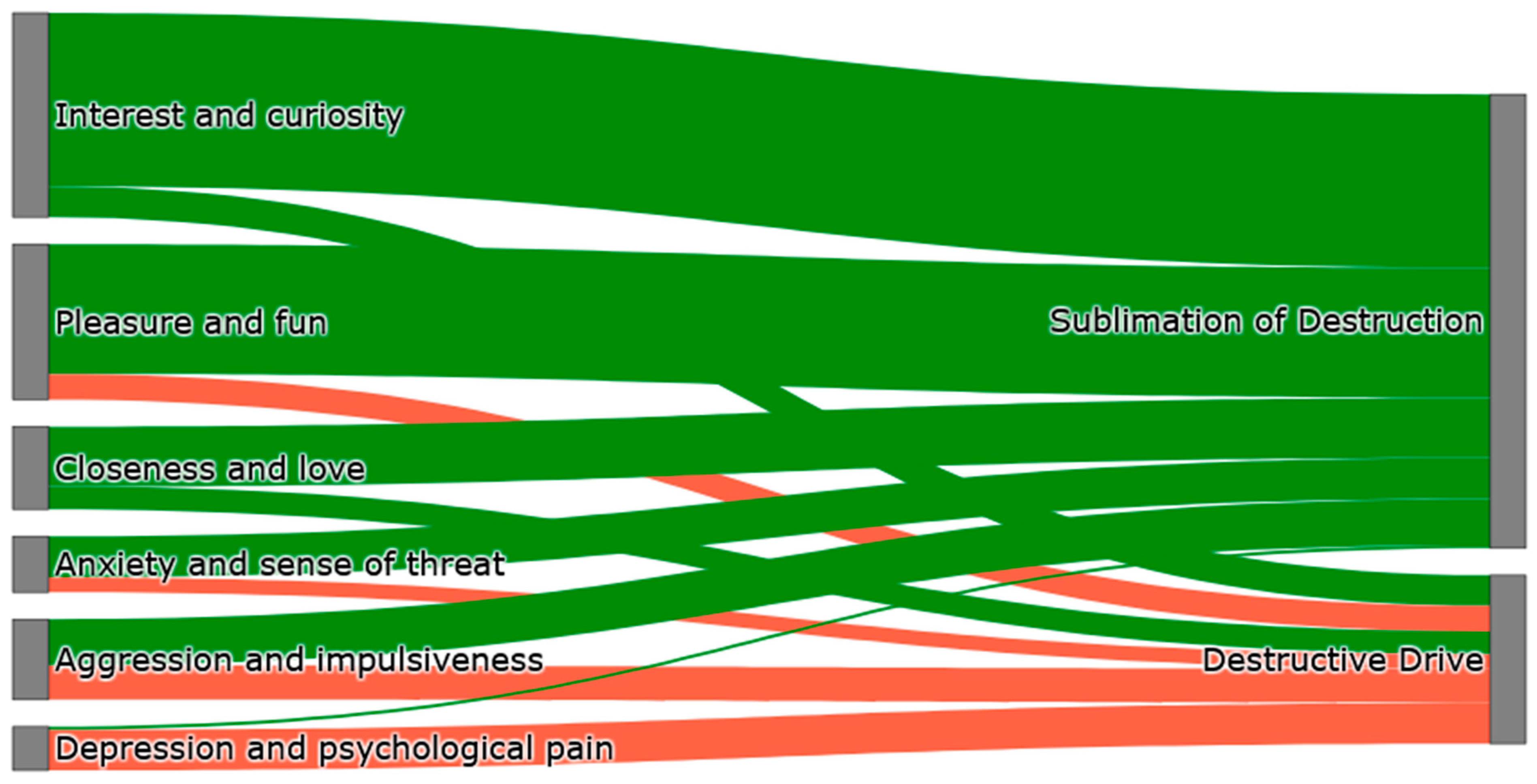

3.2.1. Destructive Drive

3.2.2. Sublimation of Destruction

3.3. Modelling Destructive Tendencies: Statistical Pathways to Risk and Transformation

3.3.1. Comparison of Univariate and Multivariate Models

Destructive Drive

Sublimation of Destruction

Age and Offspring

3.3.2. ROC Curve Analysis

3.3.3. Intergroup Differences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The satisfactory psychometric properties of the tool suggest its potential to support clinical assessment, especially in identifying patterns associated with self-aggressive tendencies. However, its diagnostic utility requires further external validation.

- The constructs of destructive drive and its sublimation appear to reflect unconscious processes, but their diagnostic relevance remains to be empirically established.

- Interest and curiosity, pleasure and fun, and closeness and love support the mechanisms of sublimation of destruction, suggesting the need to develop therapeutic strategies based on positive motivation rather than just reducing risky behaviors.

- The results of the presented research are a point of contact between the psychoanalytic approach and modern neurobiological knowledge, which opens up the possibility of integrative therapeutic methods.

- The next step in the presented study is to assess the external validity of the Morana Scale in order to determine its usefulness in clinical practice, including the assessment of suicidal risk. It is also advisable to investigate the possibility of adapting the tool to different clinical groups in order to improve the effectiveness of interventions in different therapeutic contexts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide Prevention; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Policji, K.G. Statistics on Suicide Attempts and Road Accidents; KGP: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://statystyka.policja.pl/st/wybrane-statystyki (accessed on 11 February 2025). (In Polish)

- Ajluni, V.; Amarasinghe, D. Youth suicide crisis: Identifying at-risk individuals and prevention strategies. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Esang, M.; Moll, J.; Gupta, N. Inpatient suicide: Epidemiology, risks, and evidence-based strategies. CNS Spectr. 2023, 28, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doupnik, S.K.; Rudd, B.; Schmutte, T.; Worsley, D.; Bowden, C.F.; McCarthy, E.; Eggan, E.; Bridge, J.A.; Marcus, S.C. Association of suicide prevention interventions with subsequent suicide attempts, linkage to follow-up care, and depression symptoms for acute care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, M.P.; Pawelczyk, T. Suicide risk assessment scales for adults in clinical psychology and psychiatry practice: A review of available tools. Psychiatr. Psychol. Klin. 2018, 18, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M.; Wang, L.; Mu, G.M.; Lu, Y.; So, C.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.W.-B.; et al. Measuring the suicidal mind: The ‘open source’ Suicidality Scale, for adolescents and adults. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, M.M.; Murphy, M.; Meehan, E.; Dillon, C.B.; O’Connell, S.; Hegarty, J.; Heffernan, S.; Greaney, S.; Kilty, C.; Goodwin, J.; et al. Suicide and self-harm risk assessment: A systematic review of prospective research. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022, 26, 1645–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilienfeld, S.O.; Wood, J.M.; Garb, H.N. The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2000, 1, 27–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.E.; Twibell, A.; Carroll, E.J. The current status of “projective” tests. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Foundations, Planning, Measures, and Psychometrics, 2nd ed.; Cooper, H., Coutanche, M.N., McMullen, L.M., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillo, G.; Morra, R.C.; Esposito, D.; Romani, M. Projective in time: A systematic review on the use of construction projective techniques in the digital era—Beyond inkblots. Children 2025, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, P. Protecting the Self: Defense Mechanisms in Action; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, N. Psychoanalytic Diagnosis: Understanding Personality Structure in the Clinical Process, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, A. The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense; International Universities Press: Madison, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. The Ego and the Id; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kacperska, A. Sources of psychodynamic psychotherapy: A review of selected psychoanalytic concepts. In Psychoterapia Psychodynamiczna. Teoria, Praktyka, Neuronauka; Gierus, J., Koweszko, T., Eds.; Edra Urban & Partner: Wrocław, Poland, 2024. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard, J.; Jacoby, J. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koweszko, T. Psychodynamic crisis intervention. In Psychoterapia Psychodynamiczna. Teoria, Praktyka, Neuronauka; Gierus, J., Koweszko, T., Eds.; Edra Urban & Partner: Wrocław, Poland, 2024; pp. 321–338. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US); National Research Council (US) Committee on the Science of Adolescence. The Science of Adolescent Risk-Taking: Workshop Report; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53414/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Cai, H.; Xie, X.M.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, X.; Lin, J.X.; Sim, K.; Ungvari, G.S.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of suicidality in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 690130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska-Domagała, K.; Juraś-Darowny, M.; Podlecka, M.; Lewandowska, A.; Pietras, T.; Mokros, Ł. Can morning affect protect us from suicide? The mediating role of general mental health in the relationship between chronotype and suicidal behavior among students. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 163, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsolini, L.; Latini, R.; Pompili, M.; Serafini, G.; Volpe, U.; Vellante, F.; Fornaro, M.; Valchera, A.; Tomasetti, C.; Fraticelli, S.; et al. Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: From research to clinics. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ranieri, W.F. Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report instrument for measuring suicidal ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979, 47, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.M.; Gunnell, D.; Turecki, G. Suicide risk assessment and intervention in people with mental illness. BMJ 2015, 351, h4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, T.E., Jr.; Brown, J.S.; Wingate, L.R. The psychology and neurobiology of suicidal behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E., Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, N.; Scherer, S.; Krajewski, J.; Schnieder, S.; Epps, J.; Quatieri, T.F. A review of depression and suicide risk assessment using speech analysis. Speech Commun. 2015, 71, 10–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D.M.; Mathias, C.W.; Marsh-Richard, D.M.; Prevette, K.N.; Dawes, M.A.; Hatzis, E.S.; Palmes, G.; Nouvion, S.O. Impulsivity and clinical symptoms among adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury with or without attempted suicide. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 169, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, J.; Cox, B.J.; Afifi, T.O.; de Graaf, R.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Have, M.T.; Stein, M.B. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.C.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Huang, X.; Musacchio, K.M.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 187–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koweszko, T.; Gierus, J.; Kosiński, M.; Mosiołek, A.; Szulc, A. Epidemiology of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in patients of the Clinic of Psychiatry at the Faculty of Health Sciences of Medical University of Warsaw (April 2016–March 2017). Psychiatria 2017, 14, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Shneidman, E.S. The suicidal process. In The Suicidal Crisis; Golden, M., Ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chodkiewicz, J.; Miniszewska, J.; Strzelczyk, D.; Gąsior, K. Polish adaptation of the Psychache Scale by Ronald Holden and co-workers. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbach, I.; Mikulincer, M.; Gilboa-Schechtman, E.; Sirota, P. Mental pain and its relationship to suicidality and life meaning. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2003, 33, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, M.P.; Nelson, M.C.; Pickering, M.A.; Appleby, K.M.; Grindley, E.J.; Larkins, L.W.; Baker, R.T. Measuring psychological pain: Psychometric analysis of the Orbach and Mikulincer Mental Pain Scale. Meas. Instrum. Soc. Sci. 2021, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, P.R.; Dunn, G.; Kelly, B.D.; Birkbeck, G.; Dalgard, O.S.; Lehtinen, V.; Britta, S.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Dowrick, C.; ODIN Group. Factors associated with suicidal ideation in the general population. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 189, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Subramany, R.; Amira, L.; Mann, J.J. From uniform definitions to prediction of risk: The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale approach to suicide risk assessment. In Suicide: Phenomenology and Neurobiology; Cannon, K., Hudzik, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, A.K.; Hasking, P.; Martin, G. Suicidality among adolescents engaging in nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) and firesetting: The role of psychosocial characteristics and reasons for living. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.C. Suicide risk assessment in clinical practice: Pragmatic guidelines for imperfect assessments. Psychotherapy 2012, 49, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K.; Brenner, L.A.; Galfalvy, H.C.; Currier, G.W.; Knox, K.L.; Chaudhury, S.R.; Bush, A.L.; Green, K.L. Comparison of the Safety Planning Intervention With Follow-up vs Usual Care of Suicidal Patients Treated in the Emergency Department. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breton, J.J.; Labelle, R.; Berthiaume, C.; Royer, C.; St-Georges, M.; Ricard, D.; Abadie, P.; Gérardin, P.; Cohen, D.; Guilé, J.-M. Protective factors against depression and suicidal behaviour in adolescence. Can. J. Psychiatry 2015, 60 (Suppl. S1), S5–S15. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, K.; Salvatier, J.; Dafoe, A.; Zhang, B.; Evans, O. When will AI exceed human performance? Evidence from AI experts. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 62, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini, J.; Avgeropoulos, N.; Samsam, M. Epidemiology of Brain and Spinal Tumors, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. AI Key Terms Glossary & Definition [Internet]; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://hai.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/2023-03/AI-Key-Terms-Glossary-Definition.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Pestian, J.P.; Grupp-Phelan, J.; Bretonnel Cohen, K.; Meyers, G.; Richey, L.A.; Matykiewicz, P.; Sorter, M.T. A controlled trial using natural language processing to examine the language of suicidal adolescents in the emergency department. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2016, 46, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak-Corren, Y.; Castro, V.M.; Javitt, S.; Nock, M.K.; Smoller, J.W.; Reis, B.Y. Improving risk prediction for target subpopulations: Predicting suicidal behaviors among multiple sclerosis patients. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0277483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozek, D.C.; Andres, W.C.; Smith, N.B.; Leifker, F.R.; Arne, K.; Jennings, G.; Dartnell, N.; Bryan, C.J.; Rudd, M.D. Using machine learning to predict suicide attempts in military personnel. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautzky, A.; Dold, M.; Bartova, L.; Spies, M.; Vanicek, T.; Souery, D.; Montgomery, S.; Mendlewicz, J.; Zohar, J.; Fabbri, C.; et al. Refining prediction in treatment-resistant depression: Results of machine learning analyses in the TRD III sample. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 79, 14989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewski, A.C.; Morris, R.R.; Nock, M.K. Randomized controlled trial of an online machine learning-driven risk assessment and intervention platform for increasing the use of crisis services. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 87, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsapoor Mah Parsa, M.; Koudys, J.W.; Ruocco, A.C. Suicide risk detection using artificial intelligence: The promise of creating a benchmark dataset for research on the detection of suicide risk. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1186569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtemam, H.; Sadeghi Esfahlani, S.; Sanaei, A.; Ghaemi, M.M.; Hajesmaeel-Gohari, S.; Rahimisadegh, R.; Bahaadinbeigy, K.; Ghasemian, F.; Shirvani, H. Role of machine learning algorithms in suicide risk prediction: A systematic review-meta analysis of clinical studies. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, L.; Pasquarella, C.; Odone, A.; Colucci, M.E.; Costanza, A.; Serafini, G.; Aguglia, A.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Brakoulias, V.; Amore, M.; et al. Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.P.; Gorenstein, C. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szyjewski, A. Religion of the Slavs; Wydawnictwo WAM: Kraków, Poland, 2003. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kempiński, A.M. Encyclopedia of the Mythology of Indo-European Peoples; Iskry: Warszawa, Poland, 2000. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp, J.; Biven, L. The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotion; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Murawiec, S. The primary-process emotional brain systems, according to Jaak Panksepp’s conceptualization, can serve as a component enabling the understanding of psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Psychiatr. Spersonalizowana 2023, 2, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żechowski, C. Theory of drives and emotions—From Sigmund Freud to Jaak Panksepp. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.L.; Montag, C. Selected principles of Pankseppian affective neuroscience. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Davis, K.L. Affective neuroscience theory and personality: An update. Pers. Neurosci. 2018, 1, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihura, J.L.; Meyer, G.J.; Dumitrascu, N.; Bombel, G. The validity of individual Rorschach variables: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the comprehensive system. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 548–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchshuber, J.; Prandstätter, T.; Andres, D.; Roithmeier, L.; Schmautz, B.; Freund, A.; Schwerdtfeger, A.; Unterrainer, H.-F. The German version of the brief affective neuroscience personality scales including a LUST scale (BANPS-GL). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1213156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikelenboom, M.; Smit, J.H.; Beekman, A.T.; Penninx, B.W. Do depression and anxiety converge or diverge in their association with suicidality? J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, K.R.; Meldrum, S.; Wieczorek, W.F.; Duberstein, P.R.; Welte, J.W. The association of irritability and impulsivity with suicidal ideation among 15- to 20-year-old males. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2004, 34, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, F.R.; Doughty, H.; Neumann, T.; McClelland, H.; Allott, C.; O’Connor, R.C. Impulsivity, aggression, and suicidality relationship in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 10, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busby Grant, J.; Batterham, P.J.; McCallum, S.M.; Werner-Seidler, A.; Calear, A.L. Specific anxiety and depression symptoms are risk factors for the onset of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in youth. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 327, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.; Jamil, R.T.; Fleisher, C.; Torrico, T.J. Borderline personality disorder. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bresin, K.; Hunt, R.A. The downside of being open-minded: The positive relation between openness to experience and nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2023, 53, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, E.; Bibby, P.A. Openness to experience and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis and r(equivalent) from risk ratios and odds ratios. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duberstein, P.R. Openness to experience and completed suicide across the second half of life. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1995, 7, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Raya, M.; Ogunyemi, A.O.; Rojas Carstensen, V.; Broder, J.; Illanes-Manrique, M.; Rankin, K.P. The reciprocal relationship between openness and creativity: From neurobiology to multicultural environments. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1235348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L.; Shahar, G.; Lawless, M.S.; Sells, D.; Tondora, J. Play, pleasure, and other positive life events: “Non-specific” factors in recovery from mental illness? Psychiatry 2006, 69, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esch, T.; Stefano, G.B. The neurobiology of pleasure, reward processes, addiction and their health implications. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2004, 25, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Snir, S.; Gavron, T.; Maor, Y.; Haim, N.; Sharabany, R. Friends’ closeness and intimacy from adolescence to adulthood: Art captures implicit relational representations in joint drawing: A longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Gross, M.M.; Calleja-Agius, J.; Turner, J.D. The yin and yang of the oxytocin and stress systems: Opposites, yet interdependent and intertwined determinants of lifelong health trajectories. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1272270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shean, M.; Mander, D. Building emotional safety for students in school environments: Challenges and opportunities. In Health and Education Interdependence; Midford, R., Nutton, G., Hyndman, B., Silburn, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbart, A.; Bergstedt, A.; Levander, S. Love, work, and striving for the self in balance: Anaclitic and introjective patients’ experiences of change in psychoanalysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, E. Sublimation, substitution and social anxiety. Essaim 2019, 36, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Iwaszuk, M. Between thought and action: Symbolization in depressive position and its external expressions. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2021, 12, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Thieberger, J. The concept of reparation in Melanie Klein’s writing. Melanie Klein Object Relat. 1991, 9, 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Cyr, V.M. Creating a void or sublimation in Lacan. Rech. Psychanal. 2012, 13, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobus, D. Lacan’s clinical artistry: On sublimation, sublation and the sublime. In Critique of Psychoanalytic Reason, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Campisi, S.C.; Carducci, B.; Akseer, N.; Zasowski, C.; Szatmari, P.; Bhutta, Z.A. Suicidal behaviours among adolescents from 90 countries: A pooled analysis of the global school-based student health survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, N.; Luo, Y.; Mackay, L.E.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shiferaw, B.D.; Wang, J.; Tang, J.; Yan, W.; et al. Global patterns and trends of suicide mortality and years of life lost among adolescents and young adults from 1990 to 2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2024, 33, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A.; Tele, A.; Kumar, M. Mental health service preferences of patients and providers: A scoping review of conjoint analysis and discrete choice experiments from global public health literature over the last 20 years (1999–2019). BMC Health Serv Res. 2021, 21, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quinonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemplewska-Żakowicz, K.; Paluchowski, W.J. The reliability of projective techniques as tools of psychological assessment. Part 1: Why it is unjustified to describe some of them as projective? Probl. Forensic Sci. 2013, 93, 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Di Plinio, S. Panta Rh-AI: Assessing multifaceted AI threats on human agency and identity. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Woman | 156 | 76.47 |

| Man | 48 | 23.52 | |

| Age | 18–66 | ||

| Marital status | Free | 136 | 66.66 |

| Marriage | 55 | 26.96 | |

| Divorce | 11 | 5.39 | |

| Widowhood | 2 | 0.98 | |

| Number of children | 0 | 157 | 76.96 |

| 1 | 16 | 7.84 | |

| 2 | 23 | 11.27 | |

| 3 | 7 | 3.43 | |

| More | 1 | 0.49 | |

| Education | Basic | 1 | 0.49 |

| Grammar school | 1 | 0.49 | |

| Essential professional | 3 | 1.47 | |

| Average | 76 | 37.25 | |

| Higher | 123 | 60.29 | |

| Domicile | Village | 34 | 16.66 |

| A city below 100 thousand | 33 | 16.17 | |

| City 100–500 thousand | 18 | 8.82 | |

| City over 500 thousand | 119 | 58.33 | |

| Professional activity | Education | 80 | 39.21 |

| Professional career | 116 | 56.86 | |

| Unemployment | 8 | 3.92 | |

| Psychiatric treatment currently or in the past | No | 82 | 40.19 |

| Yes | 122 | 59.80 | |

| Psychotherapy now or in the past | No | 74 | 36.27 |

| Yes | 130 | 63.72 | |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | No Yes | 83 121 | 40.68 59.32 |

| Reported disorders: | |||

| Affective Disorder F30–F39 Psychotic disorders F20–F29 Personality Disorders F60–F69 Anxiety Disorders F40–F49 | 98 3 4 16 | 48.04 1.47 1.96 7.83 | |

| The impact of the diagnosis on current well-being | Not applicable | 74 | 36.27 |

| No | 30 | 14.70 | |

| Yes | 100 | 49.01 |

| Subscale | Number of Items | Alfa Cronbach (Pearson) | Alfa Cronbach (Tetrachoric) | Omega McDonald (Total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Depression and Psychological Pain | 18 | 0.85 | 0.857 | 0.947 |

| (2) Interests and Curiosity | 15 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| (3) Aggression and Impulsiveness | 14 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| (4a) Destructive Drive | 8 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.898 |

| (4b) Sublimation of Destruction | 11 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.92 |

| (5) Pleasure and Fun | 14 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| (6) Closeness and Love | 7 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

| (7) Anxiety and Sense of Threat | 9 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.90 |

| Variable | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4a | P4b | P5 | P6 | P7 | Age | Number of Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 1 | −0.06 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.31 | −0.08 | −0.02 |

| P2 | −0.06 | 1 | 0.12 | −0.06 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 0.11 | −0.01 |

| P3 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.57 | −0.05 | −0.02 |

| P4a | 0.48 | −0.06 | 0.44 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.25 | −0.2 | −0.08 |

| P4b | 0.09 | 0.76 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.6 | 0.17 | 0.09 | −0.01 |

| P5 | 0.05 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.08 |

| P6 | −0.03 | 0.65 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.1 |

| P7 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Age | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.2 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Number of children | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.6 | 1 |

| Destructive Drive | ||||

| Factor | Single-Variate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size | Multivariate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size |

| Depression and psychological pain | B = 0.33, SE = 0.05, Wald χ2 = 47.57, p = 0.00, OR = 1.39, 95% CI [1.26–1.52] | Big impact | B = 0.29, SE = 0.05, Wald χ2 = 32.77, p = 0.00, OR = 1.33, 95% CI [1.21–1.47] | Big impact |

| Interest and curiosity | B = −0.05, SE = 0.05, Wald χ2 = 1.02, p = 0.31, OR = 0.95, 95% CI [0.87–1.05] | Lack | B = −0.29, SE = 0.14, Wald χ2 = 4.47, p = 0.03, OR = 0.75, 95% CI [0.57–0.98] | Medium (protective) effect |

| Aggression and impulsiveness | B = 0.52, SE = 0.11, Wald χ2 = 23.81, p = 0.00, OR = 1.68, 95% CI [1.36–2.06] | Big impact | B = 0.25, SE = 0.14, Wald χ2 = 3.36, p = 0.07, OR = 1.28, 95% CI [0.98–1.68] | Small effect |

| Sublimation of destruction | B = 0.10, SE = 0.07, Wald χ2 = 2.35, p = 0.13, OR = 1.11, 95% CI [0.97–1.26] | Lack | B = 0.13, SE = 0.13, Wald χ2 = 1.02, p = 0.31, OR = 1.14, 95% CI [0.88–1.48] | Lack |

| Pleasure and fun | B = 0.14, SE = 0.07, Wald χ2 = 3.67, p = 0.06, OR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.00–1.32] | Lack | B = 0.19, SE = 0.13, Wald χ2 = 2.14, p = 0.14, OR = 1.21, 95% CI [0.94–1.57] | Small effect |

| Closeness and love | B = −0.11, SE = 0.10, Wald χ2 = 1.32, p = 0.25, OR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.73–1.08] | Low (protective) effect | B = −0.21, SE = 0.14, Wald χ2 = 2.07, p = 0.15, OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.61–1.08] | Low (protective) effect |

| Anxiety and sense of threat | B = 0.44, SE = 0.10, Wald χ2 = 18.07, p = 0.00, OR = 1.55, 95% CI [1.27–1.91] | Big impact | B = 0.11, SE = 0.14, Wald χ2 = 0.65, p = 0.42, OR = 1.12, 95% CI [0.85–1.48] | No effect |

| Sublimation of Destruction | ||||

| Factor | Single-Variate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size | Multivariate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size |

| Depression and psychological pain | B = 0.07, SE = 0.03, Wald χ2 = 4.74, p = 0.03, OR = 1.07, 95% CI [1.01–1.14] | Lack | B = 0.03, SE = 0.07, Wald χ2 = 0.14, p = 0.71, OR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.90–1.17] | Lack |

| Interest and curiosity | B = 1.15, SE = 0.13, Wald χ2 = 75.97, p = 0.00, OR = 3.15, 95% CI [2.43–4.09] | Big impact | B = 0.89, SE = 0.15, Wald χ2 = 33.24, p = 0.00, OR = 2.43, 95% CI [1.80–3.29] | Big impact |

| Aggression and impulsiveness | B = 0.30, SE = 0.08, Wald χ2 = 13.87, p = 0.00, OR = 1.35, 95% CI [1.15–1.58] | Medium effect | B = 0.32, SE = 0.16, Wald χ2 = 4.20, p = 0.04, OR = 1.38, 95% CI [1.01–1.88] | Medium effect |

| Destructive drive | B = 0.12, SE = 0.07, Wald χ2 = 3.06, p = 0.08, OR = 1.13, 95% CI [0.99–1.29] | Lack | B = −0.21, SE = 0.16, Wald χ2 = 1.71, p = 0.19, OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.59–1.11] | Small effect |

| Pleasure and fun | B = 1.13, SE = 0.16, Wald χ2 = 51.54, p = 0.00, OR = 3.08, 95% CI [2.26–4.20] | Big impact | B = 0.73, SE = 0.20, Wald χ2 = 13.41, p = 0.00, OR = 2.07, 95% CI [1.40–3.06] | Big impact |

| Closeness and love | B = 1.23, SE = 0.17, Wald χ2 = 55.32, p = 0.00, OR = 3.43, 95% CI [2.48–4.76] | Big impact | B = 0.40, SE = 0.19, Wald χ2 = 4.41, p = 0.04, OR = 1.49, 95% CI [1.03–2.18] | Medium effect |

| Anxiety and sense of threat | B = 0.36, SE = 0.09, Wald χ2 = 14.66, p = 0.00, OR = 1.43, 95% CI [1.19–1.73] | Medium effect | B = 0.29, SE = 0.20, Wald χ2 = 2.08, p = 0.15, OR = 1.34, 95% CI [0.90–2.00] | Small effect |

| Destructive Drive | ||||

| Variable | Single-Variate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size | Multivariate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size |

| Age | B = −0.04, SE = 0.01, Wald χ2 = 11.86, p = 0.00, OR = 0.96, 95% CI [0.94–0.98] | Poor | B = −0.05, SE = 0.02, Wald χ2 = 13.68, p = 0.00, OR = 0.95, 95% CI [0.92–0.98] | Poor |

| Number of children | B = 0.01, SE = 0.10, Wald χ2 = 0.01, p = 0.94, OR = 1.01, 95% CI [0.83–1.23] | Lack | B = 0.24, SE = 0.15, Wald χ2 = 2.58, p = 0.11, OR = 1.28, 95% CI [0.95–1.72] | Lack |

| Sublimation of Destruction | ||||

| Variable | Single-Variate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size | Multivariate Model (B, SE, Wald χ2, p, OR, 95% CI) | Effect Size |

| Age | B = 0.01, SE = 0.01, Wald χ2 = 1.10, p = 0.29, OR = 1.01, 95% CI [0.99–1.03] | Lack | B = 0.01, SE = 0.01, Wald χ2 = 0.38, p = 0.54, OR = 1.01, 95% CI [0.98–1.03] | Lack |

| Number of children | B = 0.12, SE = 0.10, Wald χ2 = 1.32, p = 0.25, OR = 1.13, 95% CI [0.92–1.38] | Lack | B = 0.09, SE = 0.11, Wald χ2 = 0.64, p = 0.42, OR = 1.09, 95% CI [0.88–1.36] | Lack |

| Destructive Drive | ||||||||||

| Variables | AUC | SE | Cl 95% | Cut-off Point | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | Youden Index |

| Depression and psychological pain | 0.78 * | 0.04 | [0.71; 0.86] | 3 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.89 | 0.40 |

| Aggression and impulsiveness | 0.72 * | 0.04 | [0.63; 0.80] | 1 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.43 | 0.88 | 0.41 |

| Anxiety and sense of threat | 0.62 ** | 0.05 | [0.52; 0.72] | 2 | 0.40 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.30 |

| Sublimation of Destruction | ||||||||||

| Variables | AUC | SE | Cl 95% | Cut-off Point | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | Youden Index |

| Interest and curiosity | 0.90 * | 0.03 | [0.85; 0.95] | 2 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.94 | 0.71 |

| Pleasure and fun | 0.79 * | 0.04 | [0.71; 0.87] | 1 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 0.52 |

| Closeness and love | 0.84 * | 0.04 | [0.77; 0.91] | 1 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.57 | 0.94 | 0.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koweszko, T.; Kukulska, N.; Gierus, J.; Silczuk, A. Construction and Initial Psychometric Validation of the Morana Scale: A Multidimensional Projective Tool Developed Using AI-Generated Illustrations. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197069

Koweszko T, Kukulska N, Gierus J, Silczuk A. Construction and Initial Psychometric Validation of the Morana Scale: A Multidimensional Projective Tool Developed Using AI-Generated Illustrations. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):7069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197069

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoweszko, Tytus, Natalia Kukulska, Jacek Gierus, and Andrzej Silczuk. 2025. "Construction and Initial Psychometric Validation of the Morana Scale: A Multidimensional Projective Tool Developed Using AI-Generated Illustrations" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 7069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197069

APA StyleKoweszko, T., Kukulska, N., Gierus, J., & Silczuk, A. (2025). Construction and Initial Psychometric Validation of the Morana Scale: A Multidimensional Projective Tool Developed Using AI-Generated Illustrations. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 7069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197069