Effectiveness of Electroencephalographic Neurofeedback for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. EEG Neurofeedback

1.2. EEG Neurofeedback for Parkinson’s Disease

1.3. The Present Review and Meta-Analysis: Aims and Objectives

1.4. Primary Objectives

- 1.

- Determine whether EEG neurofeedback promotes targeted modulation of EEG activity in people with PD.

- 2.

- Determine the effects of EEG neurofeedback interventions on motor function/symptomology in people with PD.

1.5. Secondary Objectives

- Provide a narrative discussion of EEG neurofeedback studies in people with PD, considering features such as risk of bias, certainty of evidence, neurofeedback protocol used, and EEG and motor outcome measures, to aid the interpretation of the meta-analytical results.

- Identify targeted avenues emerging from the literature for future EEG neurofeedback research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Management

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Meta-Analysis

2.7. Subgroup Analysis

2.8. Assessment of Reporting Bias (Certainty of Evidence)

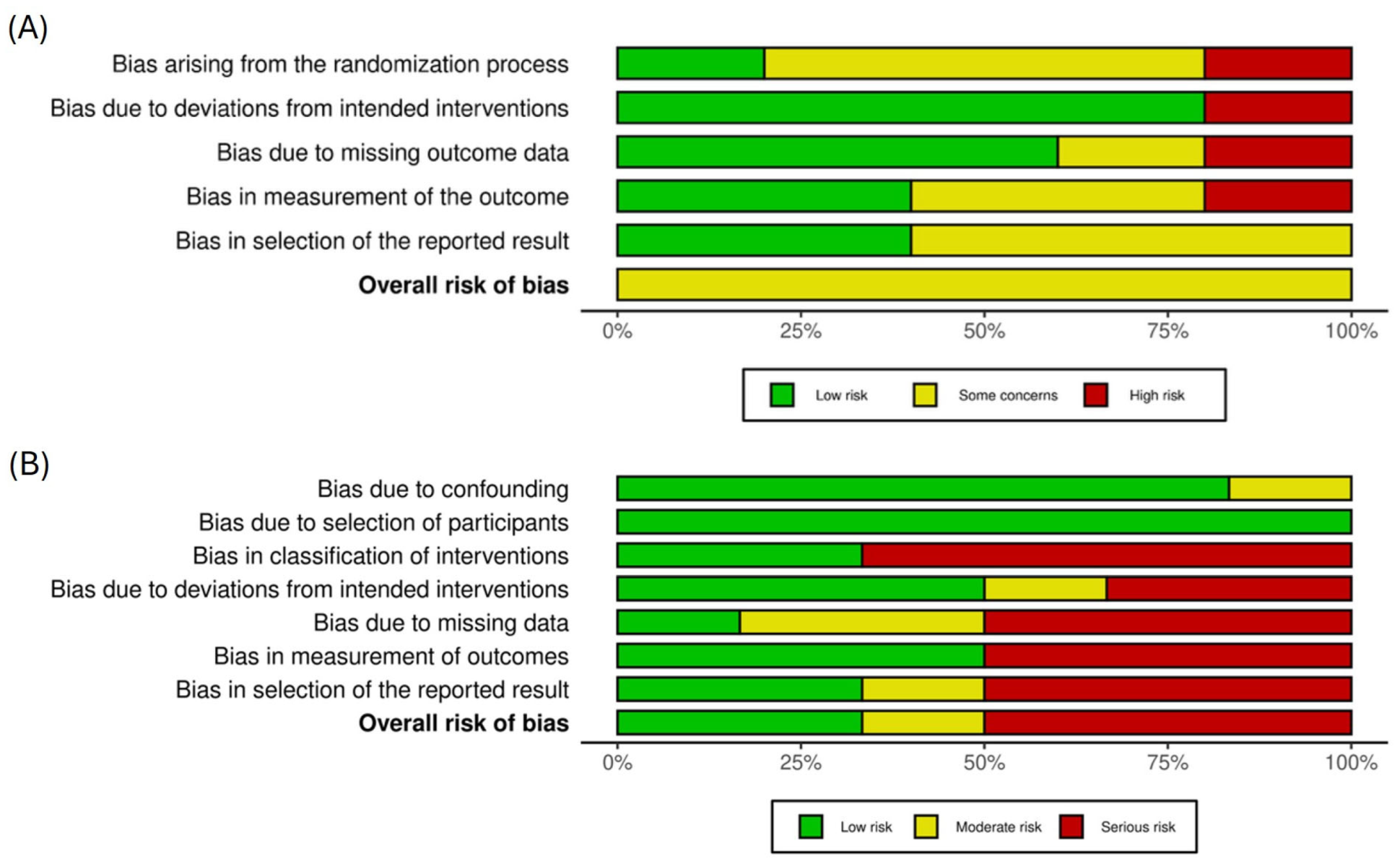

- Risk of bias: evaluated using version 2 of the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2 for the randomized parallel group or crossover trials and ROBINS-I for non-randomized studies of an intervention). See the risk of bias section above for more information.

- Inconsistency: evaluated by examining the variability in findings across studies.

- Indirectness: evaluated by establishing whether the evidence directly addresses the target population (PD patients) and intervention (EEG neurofeedback).

- Imprecision: evaluation of the precision of the effect estimates.

- Publication bias: the potential for studies with positive results to have a higher likelihood of publication.

- Large and/or consistent effect sizes

- A dose-response gradient

- Positive effects despite plausible confounds

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Included Studies

3.3. Study Quality Appraisal

3.4. Meta-Analyses

3.5. Effects of EEG Neurofeedback on Cortical Activity

3.6. Effects of EEG Neurofeedback on Motor Symptoms Assessed by UPDRS III

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of EEG Neurofeedback on Cortical Activity

4.2. Effects of EEG Neurofeedback on Motor Function

4.3. Other Effects of EEG Neurofeedback in People with Parkinson’s Disease

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Implications and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clarke, C.E. Parkinson’s disease. BMJ 2007, 335, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alty, J.E.; Clissold, B.G.; McColl, C.D.; Reardon, K.A.; Shiff, M.; Kempster, P.A. Longitudinal study of the levodopa motor response in Parkinson’s disease: Relationship between cognitive decline and motor function. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 2337–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigott, K.; Rick, J.; Xie, S.X.; Hurtig, H.; Chen-Plotkin, A.; Duda, J.E.; Morley, J.F.; Chahine, L.M.; Dahodwala, N.; Akhtar, R.S.; et al. Longitudinal study of normal cognition in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2015, 85, 1276–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Jahangeer, M.; Maknoon Razia, D.; Ashiq, M.; Ghaffar, A.; Akram, M.; El Allam, A.; Bouyahya, A.; Garipova, L.; Ali Shariati, M.; et al. Dopamine in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 522, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzerengi, S.; Clarke, C.E. Initial drug treatment in Parkinson’s disease. BMJ 2015, 351, h4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.M.; Dostrovsky, J.; Chen, R.; Ashby, P. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: Disrupting the disruption. Lancet Neurol. 2002, 1, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovic, J.; Aguilar, L.G. Current approaches to the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsych. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, F.J.; Alvarez-Vega, M.A.; Gutierrez, J.C.; Fdez-Glez, F.; Lozano, B. Complications in subthalamic nucleus stimulation surgery for treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Review of 272 procedures. Acta Neurochir. 2007, 149, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, D.C. What is neurofeedback? J. Neurother. 2007, 10, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez-Geppert, S.; Huster, R.J.; Herrmann, C.S. EEG-neurofeedback as a tool to modulate cognition and behavior: A review tutorial. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Hung, C.; Huang, C.; Chang, Y.; Lo, L.; Shen, C.; Hung, T. Expert-novice differences in SMR activity during dart throwing. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 110, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzelier, J.H. EEG-neurofeedback for optimising performance. II: Creativity, the performing arts and ecological validity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 44, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, C.; Cooke, A.; Kavussanu, M.; McIntyre, D.; Masters, R. Investigating the efficacy of neurofeedback training for expediting expertise and excellence in sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehler, D.M. Turning markers into targets–scoping neural circuits for motor neurofeedback training in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Appar. Commun. 2022, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luctkar-Flude, M.; Groll, D. A systematic review of the safety and effect of neurofeedback on fatigue and cognition. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devos, D.; Defebvre, L. Effect of deep brain stimulation and L-Dopa on electrocortical rhythms related to movement in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Brain Res. 2006, 159, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, J.P.R.; Rothwell, J.C.; Day, B.L.; Cantello, R.; Buruma, O.; Gioux, M.; Benecke, R.; Berardelli, A.; Thompson, P.D.; Marsden, C.D. The Bereitschaftspotential is abnormal in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 1989, 112, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leocani, L.; Comi, G. Movement-related event-related desynchronization in neuropsychiatric disorders. Prog. Brain Res. 2006, 159, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.K.; Fries, P. Beta-band oscillations—Signalling the status quo? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, N.; Brown, P. New insights into the relationship between dopamine, beta oscillations and motor function. Trends Neurosci. 2011, 34, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Thompson, L. Biofeedback for Movement Disorders (Dystonia with Parkinson’s Disease): Theory and Preliminary Results. J. Neurother. 2002, 6, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, F.; Linden, D.E.J. Neural Networks and Neurofeedback in Parkinson’s Disease. NeuroRegulation 2014, 1, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, K.; Hall, S.D.; Demain, S.; Freeman, J.A.; Ganis, G.; Marsden, J. A systematic review of neurofeedback for the management of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaznik, L.; Marusic, U. Exploring the Impact of Electroencephalography-Based Neurofeedback (EEG NFB) on Motor Deficits in Parkinson’s Disease: A Targeted Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.5; Cochrane: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Peacock, R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ 2005, 331, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarpaikan, A.; Torbati, H.T.; Sohrabi, M. Neurofeedback and physical balance in Parkinson’s patients. Gait Posture 2014, 40, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.J.; Pfeifer, K.J.; Tass, P.A. A single case feasibility study of sensorimotor rhythm neurofeedback in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 623317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Hindle, J.; Lawrence, C.; Bellomo, E.; Pritchard, A.W.; MacLeod, C.A.; Martin-Forbes, P.; Jones, S.; Bracewell, M.; Linden, D.E.J.; et al. Effects of home-based EEG neurofeedback training as a non-pharmacological intervention for Parkinson’s disease. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2024, 54, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson-Davis, C.; Anderson, J.S.; Wielinski, C.L.; Richter, S.A.; Parashos, S.A. Evaluation of neurofeedback training in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. J. Neurother. 2012, 16, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumuro, T.; Matsuhashi, M.; Mitsueda, T.; Inouchi, M.; Hitomi, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Matsumoto, R.; Kawamata, J.; Inoue, H.; Mima, T.; et al. Bereitschaftspotential augmentation by neuro-feedback training in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Shi, Z.; Pei, G.; Fang, B.; Yan, T. Effect of neurofeedback based on imaginary movement in Parkinson’s disease. In Proceedings of the 2023 17th International Conference on Complex Medical Engineering (CME), Suzhou, China, 3–5 November 2023; p. 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, K.; Hoshino, H.; Furusawa, Y.; DaSalla, C.S.; Honda, M.; Murata, M.; Hanakawa, T. Initial experience with a sensorimotor rhythm-based brain-computer interface in a Parkinson’s disease patient. Brain Comput. Interfaces 2018, 5, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legarda, S.B.; Michas-Martin, P.A.; McDermott, D. Managing intractable symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: A nonsurgical approach employing infralow frequency neuromodulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 894781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.P.; Moreno-Verdú, M.; Arroyo-Ferrer, A.; Serrano, J.I.; Herreros-Rodríguez, J.; García-Caldentey, J.; de Lima, E.R.; del Castillo, M.D. Clinical and neurophysiological effects of bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and EEG-guided neurofeedback in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized, four-arm controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Han, J.; Zhang, S.; Suo, W.; Wu, P.; Pei, F.; Fang, B.; Yan, T. Multimodal biofeedback for Parkinson’s disease motor and nonmotor symptoms. Brain Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.T.; Wang, K.P.; Chang, W.H.; Kao, C.W.; Hung, T.M. Effects of the function-specific instruction approach to neurofeedback training on frontal midline theta waves and golf putting performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 61, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C.; Lees, A.J.; Brown, P. Impairment of EEG desynchronisation before and during movement and its relation to bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 66, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühn, A.A.; Doyle, L.; Pogosyan, A.; Yarrow, K.; Kupsch, A.; Schneider, G.H.; Hariz, M.I.; Trottenberg, T.; Brown, P. Modulation of beta oscillations in the subthalamic area during motor imagery in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2006, 129, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, D.E. Neurofeedback and networks of depression. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 16, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, S.F.; Tan, C.H.; Hong, W.P.; Chen, K.C.; Yu, R.L. Tailoring anxiety assessment for Parkinson’s disease: The Chinese Parkinson anxiety scale with cultural and situational anxiety considerations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 381, 118284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.J.; Tan, C.H.; Hong, W.P.; Yu, R.L. Development and validation of the geriatric apathy scale: Examining multi-dimensional apathy profiles in a neurodegenerative population with cultural considerations. Asian J. Psychiatry 2024, 93, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001, 357, 1191–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population (2) | Intervention (1) | Comparison (6) | Outcome (6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Parkinson’s disease | EEG Neurofeedback training | No intervention Standard care Withdrawal of medication (OFF/ON comparison) Placebo/Sham EEG Other forms of neurofeedback Multimodal interventions | EEG activity Motor symptom severity Non-motor symptom severity Quality of life and activities of daily living Efficacy/Clinical improvement Acceptability |

| Study Authors, (Publication Year), (Country), Journal | Study Aims | Study Design | Symptom/Activity Targeted | Sample Size | Control Intervention | Follow-Up | Outcomes (As Reported) | Overall Risk of Bias (RoB2/RoBINS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azarpaikan, Torbati, and Sohrabi (2014) (Iran) Gait & Posture [37] | Evaluate the effects of EEG NF on dynamic and static balance in people with PD. | RCT | Cortical activity: increased amplitude of low beta wave (12–15 Hz) and decreased amplitude of theta wave (4–7 Hz) Motor symptoms: static and dynamic balance | n = 16 Intervention: 8 PD (4M/4F); Control: 8 PD (4M/4F) Mage = 74.7 H&Y 2.35 (SD = 0.08) | Sham EEG NF | No | Cortical activity: theta wave amplitude increased and beta wave amplitude decreased across NF sessions in the NF group. Motor symptoms: significant improvements occurred in static and dynamic balance in the intervention group. Successful use of EEG NF to train people with PD to produce prescribed patterns of cortical activity, resulting in improved balance task performance | moderate |

| Cook, Pfeifer, and Tass (2021) (USA) Frontiers in Neuroscience [38] | Explore the effects of EEG NF on SMR power (rate of SMR burst) over the motor cortex. | Case study | Cortical activity: rate, duration, and amplitude of beta and SMR bursts, RP in the beta band General motor symptoms | n = 1 1 PD, ≈55 years old, 10 years since diagnosis, H&Y 2 plus 1 pilot patient, data not reported | No control intervention (assessments made ON and OFF medication) | No | Cortical activity: rate of SMR bursts increased with each training session; the rate of beta bursts increased in the final session. Relative power in the beta band (proposed marker of PD symptom severity) decreased over the motor cortex in the last session. Motor symptoms: changes in rigidity and freezing of gait were observed. | moderate |

| Cooke et al. (2024) (UK) Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology [39] | Examine the comparative effects of PD medication versus EEG neurofeedback on central mu (9–11 Hz) power, handgrip test performance, and PD symptomatology. Test the feasibility and acceptability of EEG NF intervention in a home setting. | Experimental; within-subject design | Cortical activity: decreased central mu power Motor symptoms: Precision handgrip performance Motor Symptoms of PD: self-reported and observer-rated Non-motor symptoms: QoL Participant acceptability | n = 16 16 PD (10M/6F) Mage = 67.31 (SD = 9.77) H&Y 1−2; M years since diagnosis = 5.06 | No control intervention | No | Cortical activity: mu power recorded during handgrip task performance was greater when OFF compared to ON medication during pre-tests. Mu power progressively decreased across three (OFF medication) EEG neurofeedback training sessions. Mu power at OFF medication post-test was similar to mu power recorded during ON medication pre-test. Neurofeedback was able to mimic the effects of medication on central mu power. Motor symptoms: linear improvements in handgrip movement planning time from pre-test to post-test and across the NF training sessions. Reduced variable error (pre-test to post-test); no significant changes in absolute error or constant error. EEG NF had no effect on objective (observer-rated) motor symptoms of PD; neither medication nor EEG NF resulted in a significant change in self-report measures related to motor aspects of daily living or quality of life. Acceptability: participants perceived some benefit of the EEG NF, improved walking, improved psychological control (e.g., ability to concentrate and relax), and improved motor control; nearly all participants (13/15) would recommend EEG NF to other people with PD. | low |

| Erickson-Davis et al. (2012) (USA) Journal of Neurotherapy [40] | Examine effects of EEG neurofeedback on cortical activity, levodopa-induced dyskinesia, and other clinical features of PD. | Placebo-controlled crossover RCT | Cortical activity: increased amplitude of a 3 Hz wide band within 8–15 Hz (alpha and low beta) with concurrent decreases in amplitude in both 4–8 Hz theta and 23–34 Hz high beta Motor symptoms: L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and general motor symptoms | n = 9 Intervention: 5 PD (2M/3F) Control: 4 PD (2M/2F) Mage = 55.83 (SD = 11) H&Y 2.5 (SD = 0.35) | Sham followed by crossover EEG NF | No | Cortical activity: significant increases in alpha (8–12 Hz) and decreases in high beta (25–30 Hz) relative power post-intervention. Motor symptoms: no statistically significant differences in dyskinesia severity or in clinical features of PD. QoL: non-significant trends (home diaries) indicating a decrease in the severity of motor fluctuations. | moderate |

| Fumuro et al. (2013) (Japan) Clinical Neurophysiology [41] | Explore whether people with PD could increase readiness potential amplitude via EEG NF | Quasi-experimental; non-randomized controlled trial | Cortical activity: amplitude of the first and second components of the readiness potential—a negative-going waveform that occurs during preparation for movement Motor symptoms: not assessed | n = 21 Intervention: 10 PD (2M/8F) H&Y 3.5 (SD = 1.04) Mage =63.2 (SD = 11.45) Control: 11 age-matched healthy controls (1M/10F) | No control intervention (assessments of good NF vs. poor NF performance) | No | Cortical activity: Individual differences in responsiveness to the intervention within the intervention group. Intervention group participants were classified as good performers (slow cortical potentials differed between negative shift and positive shift training trials) or poor performers (no effect of training). Participants identified as good NF performers during the training phase appeared to learn to increase the amplitude of the early component of their readiness potential preceding a button press. | low |

| Han et al. (2023) (China) IEEE [42] | Explore whether EEG NF based on an imaginary movement strategy can regulate SMR relative power in people with PD | RCT | Cortical activity: SMR relative power Motor symptoms: mobility, balance, and risk of falling; motor aspects of experiences of daily living; and motor complications (dyskinesia and fluctuations) Non-motor symptoms: anxiety, depression, cognition, non-motor aspects of experiences of daily living | n = 14 Intervention: 7 PD (2M/5F) Control: 7PD (2M/5F) UPDRS III = 28.57 (SD = 10.7) Mage = 59.86 (SD = 8.44) | Sham EEG | No | Cortical activity: Cz SMR relative power increased significantly in the intervention group. Motor symptoms: Berg balance scale and timed up-and-go task performance improved from pre-test to post-test among members of the intervention group. No significant changes in other motor symptoms (e.g., UPDRS). Non-motor symptoms: No significant pre-test to post-test changes. | moderate |

| Kasahara et al. (2018) (Japan) Brain-Computer Interfaces [43] | Examine the effects of PD medication on the ability to modulate cortical activity via EEG neurofeedback. C3–C4 SMR (9.5–12.5 Hz) asymmetry in ON and OFF conditions | Case report | Cortical activity: C3–C4 SMR (9.5–12.5 Hz) asymmetry Motor symptoms: no target reported | n = 1 1 PD (1F) Age = 55 H&Y 2.5 | No control intervention | No | Cortical activity: The participant was able to modulate their SMR activity via NF (success rate above chance level) while they were ON their PD medication. They were unable to regulate SMR power during the OFF medication test. | high |

| Legarda, Michas-Martin, and McDermott (2022) (USA) Frontiers in Human Neuroscience [44] | A case study to document the effects of infra-low frequency EEG NF on motor symptoms of PD | Case study | Cortical activity: increased delta and decreased beta spectral power Motor symptoms: tremor, writing skill, and gait | n = 3 3 PD (1M/2F) Mage =72 (SD = 6.4 years) disease severity not reported | No control intervention | No | Improved motor symptoms (tremor, dysgraphia, and freezing of gait) were observed | high |

| Romero et al. (2024) (Spain) Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation [45] | Determine immediate and short-term effects of EEG NF, alone or in combination with bilateral rTMS, in comparison to no intervention, in people with PD receiving pharmacologic therapy. Assess the electrophysiological correlates associated with the clinical effects | RCT | Cortical activity: Reduced central alpha (9–12 Hz) and beta (18–24 Hz) power Motor symptoms: severity, functional mobility, postural stability, and motor speed Non-motor symptoms: anxiety, depression, and QoL | n = 40 Intervention: arm A (rTMS): 10 PD (7M/3F) arm B (EEG NF): 11 PD (7M/4F) arm C (rTMS + EEG NF): 10 PD (7M/3F) Control: arm D (no intervention): 9 PD (5M/3F) H&Y 1.85 (SD = 0.50) UPDRS III = 15.8 (SD = 7.76) Mage = 63 (SD = 8.26) | rTMS; rTMS + EEG NF; control (no intervention) | Yes—15 days | Cortical activity: EEG data not reported. The EEG neurofeedback appeared to impact an adjacent non-EEG cortical marker—the cortical silent period—in the hypothesized way. Motor symptoms: rTMS alone improved motor symptoms. EEG NF alone has minimal direct impact on motor symptoms, although postural stability increased across assessments (all groups). The combination of rTMS and NF improved dominant hand motor skills. Non-motor symptoms and QoL: rTMS had no effect on depression; rTMS + EEG NF and EEG NF alone had small (negligible) effects. | moderate |

| Shi et al. (2023) (China) Brain Science Advances [46] | Explore whether biofeedback improves motor and non-motor functions in people with PD by regulating abnormal EEG, cardiac, pulse, respiration, or other physiological signals | RCT | Cortical activity: increased SMR relative power Motor symptoms: severity, balance, and fall risk Non-motor symptoms: behavior, mood, anxiety, and depression | n = 21 Mage = 59.86 (SD = 8.44) UPDRS III = 30.85 (SD = 11.15) Intervention: arm A (EEG NF) 7PD (2M/5F) arm B (multimodal EEG, ECG, PPG, and RSP) 7 PD (1M/6F) arm C Control group (sham EEG NF 7 PD (2M/5F) | Sham EEG NF | Yes—12 months | Cortical activity: Main effect—SMR relative power tended to be higher in the EEG NF and the multimodal biofeedback groups compared to the Sham group. Motor symptoms: Berg balance scale and timed up-and-go task performance improved from pre- to post-test among members of the EEG NF group. There were no effects on the other tests (e.g., UPDRS), and no effects emerged for the multimodal biofeedback group. Non-motor symptoms: No effects of EEG NF. Multimodal biofeedback was associated with reduced anxiety and depression. | moderate |

| Thompson and Thompson (2002) (Canada) Journal of Neurotherapy [21] | Present a theoretical framework for a biofeedback treatment for movement disorders in PD and dystonia | Case study | General motor symptoms | n = 1 1 (0M/1F) Age = 47 Years since diagnosis = 14 | No control intervention | No | Reduction in dystonic movements by using diaphragmatic breathing to cue increased SMR production/self-reported control over freezing. | high |

| Study Reference | NF Targeted Activity/Activity Direction | NF Run Length | NF Session Length | Sessions | Total NF Exposure (Session Length × Sessions) | Time Between Sessions | Delivery Method | Instruction Given | Reported That Targeted EEG Activity Changed in the Prescribed Way |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azarpaikan, Torbati, and Sohrabi (2014) [37] | O1 and O2 Reinforce low β (12–15 Hz) activity (increase beta wave amplitude) and inhibit theta (4–7 Hz) activity (decrease theta wave amplitude) | Not reported | 30 m | 8 | 4 h | 2–3 days | Video game, puzzle, and moving animation | Not reported | Yes |

| Cook, Pfeifer, and Tass (2021) [38] | C3 and C4 Increase SMR power (12–17 Hz) and high beta (17–30 Hz) activity over the motor cortex | 5 m (10 blocks) | 50 m | 2 | 1 h 40 min | 1 day | Visual feedback (constantly updating bar graph) + point system rewarding short increases in SMR activity. | Instructed to try to raise a bar graph on screen until it turns green and keep it green as long and often as possible | Yes |

| Cooke et al. (2024) [39] | C3 and C4—reduce mu power (9–11 Hz) | 5 m (12 blocks) | 1 h | 3 | 3 h | Minimum 48 h; most common: 7 days | Audio feedback: power within the mu band from the EEG signal was fed back to participants in the form of an auditory tone; the tone was programmed to vary in pitch based on the level of mu power and silence completely when mu power was decreased by 30% (session 1), 55% (session 2), and 80% (session 3), relative to each participant’s baseline cortical activity | When thresholds were met, the auditory tone was set to silence for 1.5 s, and participants were instructed to squeeze the handgrip dynamometer with their dominant hand to produce a grip force equivalent to 10% MVC for 5 s (i.e., to initiate a trial of the precision motor task) | Yes |

| Erickson-Davis et al. (2012) [40] | C3 and C4 Reinforce alpha activity (8–15 Hz) and inhibit theta activity (4–8 Hz) and high beta (23–34 Hz) activity | Not reported | 30 m | 24 | 12 h | 1–6 days | Audio feedback | No instruction | Yes |

| Fumuro et al. (2013) [41] | C3, C1, Cz, C2, and C4 Increase readiness potential amplitude (SCP negativation to restore decreased readiness potential) | 10 s | 8.7 m | 2–4 | 18–36 min | 1–6 days | Visual feedback of the subjects’ SCPs at Cz: sunfish moved up (negative shift/negativation) or down (positive shift/positivation) depending on the SCP shift | To make introspective efforts to produce negative SCPs (negativation) | Partial (individual differences in responsiveness to NF) |

| Han et al. (2023) [42] | C3 and C4 Increase SMR power | 4 s | 14 m | 5 | 1 h 10 min | 2 days | Visual: imaginary movement blocks; NF score was represented as a visual bar (height proportional to the score, color changing to reflect performance in relation to threshold) | To perform motion imagery according to the GIF animation played on a screen | Yes |

| Kasahara et al. (2018) [43] | C3 and C4 SMR (9.5–12.5 Hz) asymmetry | 4 s | 24 m | 2 (on/off) | 48 min | 2 days | Visual: a falling cursor moved left or right to hit a target, depending on the targeted ERD (the signal used to control cursor movement was computed from the difference in the SMR amplitude between C4 and C3, where a greater ERD (decrease in power/amplitude) at C4 resulted in leftward online cursor movement and a greater ERD at C3 resulted in rightward cursor movement) | Motor imagery of the left or right hand: finger-thumb opposition to control the horizontal position of the cursor | Partial (EEG modulated ON medication only) |

| Legarda, Michas-Martin, and McDermott. (2022) [44] | T3-P3, T3-C3, and T3-F3; T4-P4, T4-C4, and T4-F4 Infra-low frequency NF expected to increase delta oscillation and suppress beta oscillation | Not reported | 50 m | 5 | 4 h 10 min | 3 days | Not reported | Not reported | Only reported for one out of three cases: yes for the reported case |

| Romero et al. (2024) [45] | C3, Cz, and C4— reduce average bilateral alpha (9–12 Hz) and beta (18–24 Hz) bands Achieve beta desynchronization | 10 s | 30 m | 8 | 4 h | 1–2 days | Visual—virtual reality Move an object in 5 different 6-min virtual environments; each scenario had a virtual object that moved (feedback) when the average PSD was at least 1 SD lower than the average resting PSD in each frequency band; this threshold was adjusted daily to encourage progression in participant’s ability to self-regulate the signal. | No explicit instruction | EEG activity not reported. Modulation of a non-EEG brain-based measure (cortical silent period) was achieved, suggesting some impact of NF on the brain |

| Shi et al. (2023) [46] | C3 and C4 Increase SMR relative power | 4 s | 14 m | 5 | 1 h 10 min | 2 days | Visual: imaginary movement blocks; NF score was represented as a visual bar (height proportional to the score, color changing to reflect performance in relation to threshold) | To perform motion imagery according to the GIF animation played on a screen | Yes |

| Thompson and Thompson (2002) [21] | FCz and CPz Reinforce low beta/SMR (13–15 Hz) Inhibit alpha (6–10 Hz) activity Inhibit high beta (25–32 Hz) activity | Not reported | 50 m | 42 | 35 h | 7 days | Visual and audio feedback (screen animations) | Not reported | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Altdorf, L.A.W.R.; Bracewell, M.; Cooke, A. Effectiveness of Electroencephalographic Neurofeedback for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196929

von Altdorf LAWR, Bracewell M, Cooke A. Effectiveness of Electroencephalographic Neurofeedback for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196929

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Altdorf, Leon Andreas W. R., Martyn Bracewell, and Andrew Cooke. 2025. "Effectiveness of Electroencephalographic Neurofeedback for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196929

APA Stylevon Altdorf, L. A. W. R., Bracewell, M., & Cooke, A. (2025). Effectiveness of Electroencephalographic Neurofeedback for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196929