Self-Perceived Health Status of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in Spain: Associated Factors and Sex Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of Variables

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

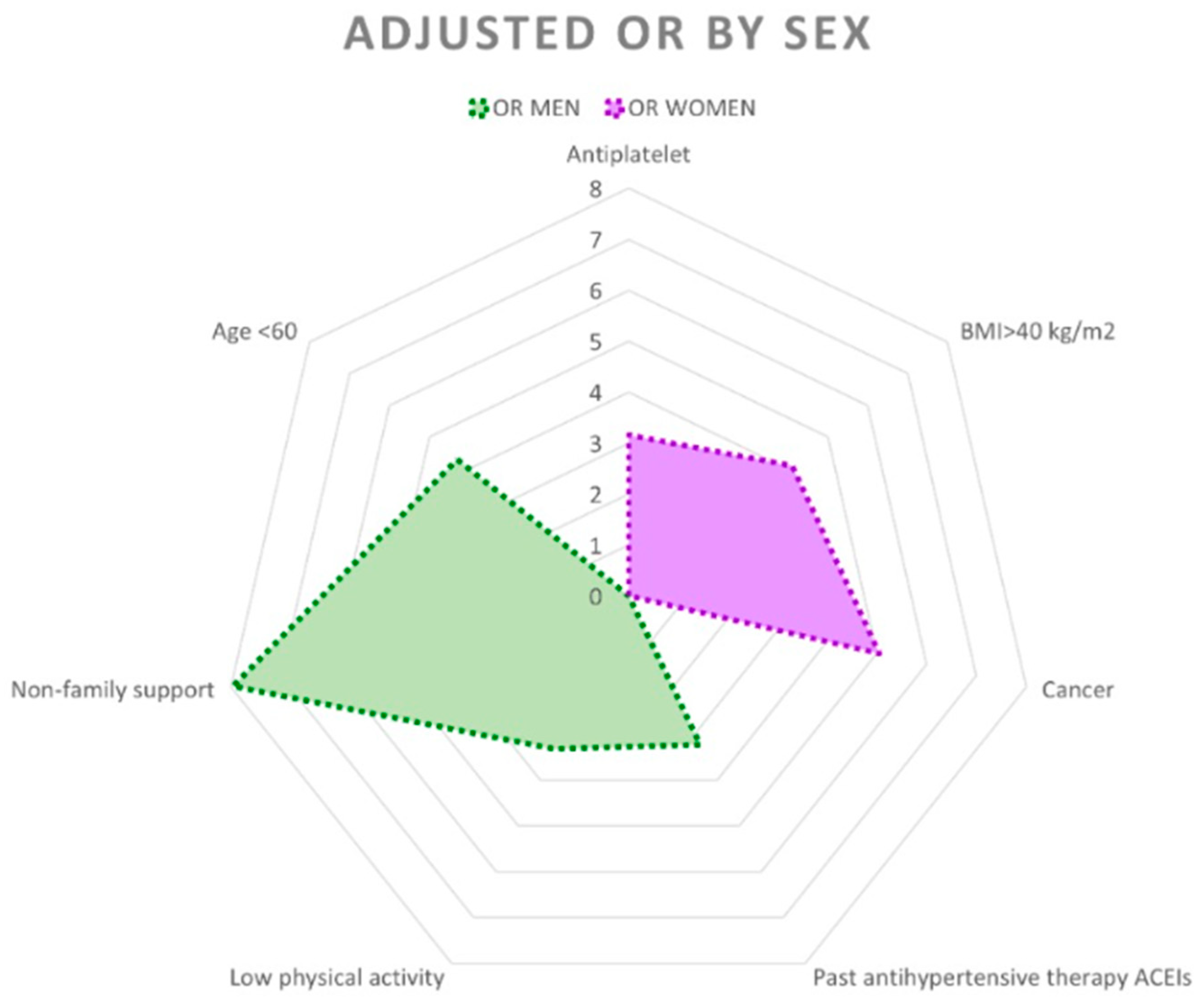

3.1. Men

3.2. Women

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACEIs/ARBs | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers |

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| aOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors |

| EMRs | Electronic medical records |

| HbA1c | Glycosylated haemoglobin, haemoglobin A1C |

| INE | National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística) |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MEDAS | Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener |

| MS | Metabolic syndrome |

| SGLT2 | Sodium–glucose cotransporter type 2 |

References

- Mossey, J.M.; Shapiro, E. Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am. J. Public Health 1982, 72, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo Cebolla, V.; de Lorenzo-Cáceres Ascanio, A.; de León, P.D.R.; Rodríguez Barrientos, R.; Torijano Castillo, M.J. Health inequalities in self-perceived health among older adults in Spain. Gac. Sanit. 2014, 28, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro López, V.; de Rovira, J.B. Social inequities of health in Spain. Report of the Scientific Commission for the Study of Social Inequities in Health in Spain. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 1996, 70, 505–636. [Google Scholar]

- van Doorslaer, E.; Koolman, X.; Jones, A.M. Explaining income-related inequalities in doctor utilisation in Europe. Health Econ. 2004, 13, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSalvo, K.B.; Bloser, N.; Reynolds, K.; He, J.; Muntner, P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idler, E.; Leventhal, H.; Mclaughlin, J.; Leventhal, E. In sickness but not in health: Self-ratings, identity, and mortality. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Sargent-Cox, K.; Anstey, K.J.; Luszcz, M.A. The choice of self-rated health measures matter when predicting mortality: Evidence from 10 years follow-up of the Australian longitudinal study of ageing. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Séculi, E.; Fusté, J.; Brugulat, P.; Juncà, S.; Rué, M.; Guillén, M. Health self-perception in men and women among the elderly. Gac. Sanit. 2001, 15, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Sánchez, J.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.; Nicola, C.M.; Nocua-Rodríguez, I.I.; Amegló-Parejo, M.R.; Del Carmen-Peña, M.; Cordero-Prieto, C.; Gajardo-Barrena, M.J. Eval-uation of a supervised physical exercise program in sedentary patients over 65 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aten. Primaria 2015, 47, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De-Mateo-Silleras, B.; Camina-Martín, M.A.; Cartujo-Redondo, A.; Enciso, L.C.; de la Cruz, S.; del Río, P.R. Health Perception According to the Lifestyle of University Students. J. Community Health 2019, 44, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios-Vicedo, R.; Navarrete-Muñoz, E.M.; de la Hera, M.G.; González-Palacios, S.; Valera-Gran, D.; Checa-Sevilla, J.F.; Gimenez-Monzo, D.; Vioque, J. A lower adherence to Mediterranean diet is associated with a poorer self-rated health in university population. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 31, 785–792. [Google Scholar]

- van Gemert, W.A.M.; van der Palen, J.; Monninkhof, E.M.; Rozeboom, A.; Peters, R.; Wittink, H.; Schuit, A.J.; Peeters, P.H.; Allison, D.B. Quality of Life After Diet or Exercise-Induced Weight Loss in Overweight to Obese Postmenopausal Women: The SHAPE-2 Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127520. [Google Scholar]

- García-Soidán, J.L.; Pérez-Ribao, I.; Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Soto-Rodríguez, A. Long-Term Influence of the Practice of Physical Activity on the Self-Perceived Quality of Life of Women with Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera-Garcimartín, A.; Sánchez-Polán, M.; López-Martín, A.; Echarri-González, M.J.; Marquina, M.; Barakat, R.; Cordente-Martínez, C.; Refoyo, I. Effects of Physical Activity Interventions on Self-Perceived Health Status Among Lung Cancer Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nombela Manzaneque, N.; Pérez-Arechaederra, D.; Caperos Montalbán, J.M. Side effects and practices to improve management of type 2 diabetes mellitus from the viewpoint of patient experience and health care management. A narrative review. En-docrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2019, 66, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarić, V.; Svirčević, V.; Bijuk, R.; Zupančič, V. Chronic Complications of Diabetes and Quality of Life. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vich-Pérez, P.; Abánades-Herranz, J.C.; Mora-Navarro, G.; Carrasco-Sayalero, Á.M.; Salinero-Fort, M.Á.; Sevilla-Machuca, I.; Sanz-Pascual, M.; Hernández-Cañizares, C.Á.; de Burgos-Lunar, C.; LADA-PC Research Consortium; et al. Development and validation of a clinical score for identifying patients with high risk of latent autoimmune adult diabetes (LADA): The LADA primary care-protocol study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, S13–S28. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, N. Essential anthropometry: Baseline anthropometric methods for human biologists in laboratory and field situations. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2013, 25, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A Short Screener Is Valid for Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence Among Older Spanish Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cho-lesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar]

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denche-Zamorano, Á.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Muñoz-Bermejo, L.; Rojo-Ramos, J.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; Godoy-Cumillaf, A.; Barrios-Fernandez, S. A Cross-Sectional Study on Self-Perceived Health and Physical Activity Level in the Spanish Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Denche-Zamorano, Á.; Pisà-Canyelles, J.; Barrios-Fernández, S.; Castillo-Paredes, A.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Gómez, D.S.; Holgado, C.M. Evaluation of the association of physical activity levels with self-perceived health, depression, and anxiety in Spanish individuals with high cholesterol levels: A retrospective cross-sectional study. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Denche-Zamorano, A.; Perez-Gomez, J.; Barrios-Fernandez, S.; Oliveira, R.; Adsuar, J.C.; Brito, J.P. Relationships between Physical Activity Frequency and Self-Perceived Health, Self-Reported Depression, and Depressive Symptoms in Spanish Older Adults with Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiménez-Garcia, R.; Jiménez-Trujillo, I.; Hernandez-Barrera, V.; Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Lopez, A.; Gil, A. Ten-year trends in self-rated health among Spanish adults with diabetes, 1993–2003. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine—Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25 (Suppl. S3), 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barreira, E.; Novo, A.; Vaz, J.A.; Pereira, A.M. Dietary program and physical activity impact on biochemical markers in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Aten. Primaria 2018, 50, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tenreiro, K.; Hatipoglu, B. Mind Matters: Mental Health and Diabetes Management. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110 (Suppl. S2), S131–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, M.E.Y.; Barrera, V.H.; Cordero, X.F.; Gil de Miguel, A.; Pérez, M.R.; Andres, A.L.-D.; Jiménez-García, R. Self-perception of health status, mental health and quality of life among adults with diabetes residing in a metropolitan area. Diabetes Metab. 2010, 36, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, K.; Gregg, E.W.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhang, P.; de Rekeneire, N.; Williamson, D.F. The association of BMI with functional status and self-rated health in US adults. Obesity 2008, 16, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 8. Obesity and Weight Management for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes–2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. S1), S167–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Self-rated fair or poor health among adults with diabetes—United States, 1996-2005. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2006, 55, 1224–1227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cuenca, A.M.C.; Escalada, J. Prevalencia de obesidad y diabetes en España. Evolución en los últimos 10 años. Aten. Primaria 2025, 57, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Young, C.F.; Shubrook, J.H.; Valencerina, E.; Wong, S.; Lo, S.N.H.; Dugan, J.A. Associations between social support and diabetes-related distress in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Osteopat. Assoc. 2020, 120, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denche-Zamorano, A.; Pisà-Canyelles, J.; Barrios-Fernandez, S.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Adsuar, J.C.; Garcia-Gordillo, M.A.; Pereira-Payo, D.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M. Is psychological distress associated with self-perceived health, perceived social support and physical activity level in Spanish adults with diabetes? J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Undén, A.-L.; Elofsson, S.; Andréasson, A.; Hillered, E.; Eriksson, I.; Brismar, K. Gender differences in self-rated health, quality of life, quality of care, and metabolic control in patients with diabetes. Gend. Med. 2008, 5, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarini, G.G.; Vaccaro, J.A.; Terris, M.A.C.; Exebio, J.C.; Tokayer, L.; Antwi, J.; Ajabshir, S.; Cheema, A.; Huffman, F.G. Lifestyle behaviors and self-rated health: The living for health program. J. Environ. Public Health 2014, 2014, 315042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zajacova, A.; Huzurbazar, S.; Todd, M. Gender and the structure of self-rated health across the adult life span. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 187, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pérez-Tasigchana, R.F.; León-Muñoz, L.M.; López-García, E.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Hribal, M.L. Mediterranean Diet and Health-Related Quality of Life in Two Cohorts of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151596. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Salud Autopercibida. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?L=es_ES&c=INESeccion_C&cid=1259944485720&p=1254735110672&pagename=ProductosYServicios%2FPYSLayout¶m1=PYSDetalleFichaIndicador¶m3=1259937499084 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Arcega-Domínguez, A.; Lara-Muñoz, C.; Ponce-De-León-Rosales, S. Factors related to subjective evaluation of quality of life of diabetic patients. Rev. Investig. Clin. Órgano. Hosp. Enfermedades Nutr. 2005, 57, 676–684. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, F.; Suprani, F.; Deiana, V.; Lai, L.; Manchia, M.; Paribello, P.; Somaini, G.; Diana, E.; Nicotra, E.F.; Farci, F.; et al. Depression in Diabetic Patients: What Is the Link with Eating Disorders? Results of a Study in a Representative Sample of Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 848031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazukauskiene, N.; Podlipskyte, A.; Varoneckas, G.; Mickuviene, N. Health-related quality of life and insulin resistance over a 10-year follow-up. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Knifton, L.; Robb, K.A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Smith, D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azpiazu Garrido, M.; Cruz Jentoft, A.; Villagrasa Ferrer, J.R.; Abanades Herranz, J.C.; García Marín, N.; Valero de Bernabé, F.A. Factors related to perceived poor health condition or poor quality of life among those over 65 years of age. Rev. Esp. Salud. Publica 2002, 76, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli-Araujo, H. The association between social support and self-rated health in midlife: Are men more affected than women? Cad. Saude Publica 2023, 39, e00106323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, F.; Bucciarelli, V.; Moscucci, F.; Sciomer, S.; Ricci, F.; Coppi, F.; Bergamaschi, L.; Armillotta, M.; Alvarez, M.C.; Renda, G.; et al. Gender and Sex-related differences in Type 2 Myocardial Infarction: The undervalued side of a neglected disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Valencia, M.; Herce, P.A.; Lacalle-Fabo, E.; Escámez, B.C.; Cedeno-Veloz, B.; Martínez-Velilla, N. Prevalence of polypharmacy and associated factors in older adults in Spain: Data from the National Health Survey 2017. Med. Clín. 2019, 153, 141–150, (In English, Spanish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasu, R.; Agbor-Bawa, W.; Rianon, N. Impact of Polypharmacy on Seniors’ Self-Perceived Health Status. S. Med. J. 2017, 110, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machón, M.; Vergara, I.; Dorronsoro, M.; Vrotsou, K.; Larrañaga, I. Self-perceived health in functionally independent older people: Associated factors. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alonso, J.; Saha, S.; Lim, C.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Benjet, C.; Bromet, E.J.; Degenhardt, L.; de Girolamo, G.; Esan, O.; et al. The association between psychotic experiences and health-related quality of life: A cross-national analysis based on World Mental Health Surveys. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 201, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Benavent, D.; Garrido-Cumbrera, M.; Plasencia-Rodríguez, C.; Marzo-Ortega, H.; Christen, L.; Correa-Fernández, J.; Plazuelo-Ramos, P.; Webb, D.; Navarro-Compán, V. Poor health and functioning in patients with axial spondyloarthritis during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: REUMAVID study (phase 1). Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2022, 14, 1759720X211066685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Negative Self-Perceived Health (%) | p-Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Men (n = 455) | 20.2 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Women (n = 341) | 33.4 | 1.98 (1.44–2.73) | <0.001 | |

| Age Group | ||||

| ≤60 (n = 378) | 26.2 | 0.373 | 1 | |

| 61–75 (n = 303) | 23.8 | 0.88 (0.62–1.25) | 0.465 | |

| >75 (n = 115) | 30.4 | 1.23 (0.78–1.95) | 0.371 | |

| Education | ||||

| Superior education (n = 398) | 21.9 | 1 | ||

| Elementary education (n = 398) | 29.9 | 0.010 | 1.53 (1.11–2.10) | 0.010 |

| Social Support | ||||

| Family (n = 721) | 24.0 | 1 | ||

| None (n = 39) | 43.6 | 0.001 | 2.45 (1.27–4.72) | 0.001 |

| Yes, but not family social support (n = 36) | 44.4 | 2.53 (1.29–5.00) | 0.001 | |

| BMI Categories | ||||

| <25 kg/m2 (n = 120) | 27.5 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| 25–29 kg/m2 (n = 272) | 21.7 | 0.73 (0.45–1.20) | 0.212 | |

| 30–34 kg/m2 (n = 248) | 23.8 | 0.82 (0.50–1.35) | 0.441 | |

| 35–40 kg/m2 (n = 102) | 26.5 | 0.95 (0.52–1.72) | 0.863 | |

| >40 kg/m2 (n = 54) | 51.9 | 2.84 (1.46–5.53) | 0.002 | |

| CKD | ||||

| No (n = 717) | 24.0 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 79) | 43.0 | <0.001 | 2.39 (1.49–3.86) | <0.001 |

| Retinopathy | ||||

| No (n = 722) | 24.7 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 74) | 37.8 | 0.021 | 1.86 (1.13–3.07) | 0.015 |

| Neuropathy | ||||

| Yes (n = 57) | 42.1 | <0.001 | 2.23 (1.28–3.87) | <0.01 |

| No (n = 739) | 24.6 | 1 | ||

| CVD | ||||

| No (n = 639) | 22.1 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 157) | 41.4 | <0.001 | 2.50 (1.73–3.61) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| No (n = 385) | 22.3 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 411) | 29.2 | 0.026 | 1.43 (1.04–1.98) | 0.028 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | ||||

| No (n = 723) | 18.4 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 73) | 35.4 | 0.001 | 1.91 (1.15–3.15) | 0.012 |

| Respiratory Diseases | ||||

| No (n = 658) | 23.7 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 138) | 36.2 | <0.01 | 1.83 (1.24–2.70) | <0.01 |

| Psychotic Disorders | ||||

| No (n = 756) | 24.6 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 40) | 50.0 | 0.001 | 3.07 (1.61–5.82) | 0.001 |

| Mood Disorders | ||||

| No (n = 578) | 20.4 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 218) | 40.4 | <0.001 | 2.64 (1.89–3.70) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | ||||

| No (n = 708) | 24.4 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n = 88) | 37.5 | 0.012 | 1.86 (1.17–2.95) | <0.01 |

| DPP-4 Inhibitors | ||||

| Never (n = 612) | 23.9 | 0.036 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 68) | 36.8 | 1.86 (1.10–3.14) | 0.021 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 116) | 30.2 | 1.38 (0.89–2.14) | 0.150 | |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | ||||

| Never (n = 568) | 24.6 | 0.013 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 42) | 45.2 | 2.53 (1.34–4.78) | <0.01 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 186) | 25.3 | 1.03 (0.71–1.51) | 0.865 | |

| Antihypertensives Therapies, ACEIs/ARBs | ||||

| Never (n = 355) | 37.4 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 55) | 49.1 | 3.48 (1.94–6.25) | <0.001 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 386) | 26.4 | 1.30 (0.93–1.82) | 0.133 | |

| Antihypertensive Therapies, Non-ACEIs/ARBs | ||||

| Never (n = 556) | 22.7 | <0.01 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 82) | 39.0 | 2.18 (1.34–3.55) | <0.01 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 158) | 30.4 | 1.49 (1.01–2.01) | 0.047 | |

| Antiplatelet Drugs | ||||

| Never (n = 613) | 22.2 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 54) | 38.9 | 2.23 (1.25–3.98) | <0.01 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 129) | 38.0 | 2.15 (1.44–3.22) | <0.001 | |

| Psychiatric Drugs | ||||

| Never (n = 730) | 24.4 | <0.01 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 34) | 38.2 | 1.92 (0.94–3.91) | 0.073 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 32) | 46.9 | 2.74 (1.34–5.59) | <0.01 | |

| Mood Disorder Drugs | ||||

| Never (n = 638) | 23.4 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 52) | 25.0 | 1.09 (0.57–2.10) | 0.788 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 106) | 41.5 | 2.33 (1.52–3.57) | <0.001 | |

| Corticosteroids | ||||

| Never (n = 553) | 23.9 | 0.041 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 180) | 27.8 | 1.23 (0.84–1.79) | 0.292 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 63) | 38.1 | 1.96 (1.14–3.38) | 0.015 | |

| Anticancer Medication | ||||

| Never (n = 697) | 24.1 | 0.001 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 31) | 22.6 | 0.92 (0.39–2.17) | 0.846 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 68) | 45.6 | 2.64 (1.59–4.38) | <0.001 | |

| Immunomodulators | ||||

| Never (n = 711) | 23.9 | 0.001 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 27) | 40.7 | 2.19 (0.99–4.81) | 0.051 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 58) | 43.1 | 2.41 (1.39–4.17) | <0.01 | |

| Glinides | ||||

| Never (n = 742) | 25.2 | 0.068 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 12) | 16.7 | 0.59 (0.13–2.73) | 0.503 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 42) | 40.5 | 2.02 (1.07–3.82) | 0.031 | |

| Sulfonylureas | ||||

| Never (n= 699) | 23.7 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Yes, but not currently (n = 65) | 47.7 | 2.93 (1.75–4.91) | <0.001 | |

| Yes, currently (n = 32) | 28.1 | 1.26 (0.57–2.77) | 0.571 | |

| Polypharmacy | ||||

| No (n = 435) | 17.9 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Yes (n = 361) | 35.5 | 2.51 (1.81–3.49) | <0.001 | |

| Mediterranean Diet | ||||

| High adherence, ≥11 (n = 175) | 20.6 | 0.126 | 1 | |

| Medium adherence, 6–10 (n = 559) | 26.8 | 1.42 (0.94–2.14) | 0.098 | |

| Low adherence, 0–5 (n = 62) | 32.3 | 1.84 (0.96–3.51) | 0.065 | |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Moderate or high (n = 399) | 18.8 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Low (n = 397) | 33.0 | 2.13 (1.53–2.95) | <0.001 | |

| FPG | ||||

| ≥100 mg/dL | 25.9 | 0.920 | 1 | |

| <100 mg/dL | 25.0 | 0.95 (0.37–2.44) | 0.920 | |

| HbA1c | ||||

| ≥7% | 24.0 | 0.160 | 1 | |

| <7% | 28.4 | 1.26 (0.91–1.73) | 0.160 | |

| LDL Cholesterol | ||||

| ≥100 mg/dL | 27.9 | 0.071 | 1 | |

| <100 mg/dL | 22.0 | 0.83 (0.61–1.15) | 0.071 |

| Men (n = 455) | Women (n = 341) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Self-Perception (%) | p-Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Negative Self-Perception (%) | p-Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age Group | 0.042 | 0.200 | ||||||

| >75 years | 12.2 | 1 | 40.5 | 1 | ||||

| 61–75 years | 16.2 | 1.39 (0.50–3.85) | 0.524 | 34.7 | 0.78 (0.43–1.41) | 0.408 | ||

| <60 years | 24.7 | 2.36 (0.88–630) | 0.086 | 28.7 | 0.59 (0.33–1.06) | 0.079 | ||

| Education | 0.379 | 0.034 | ||||||

| Superior education | 18.7 | 1 | 27.2 | 1 | 0.035 | |||

| Elementary education | 22.1 | 1.23 (0.78–1.94) | 0.379 | 38.1 | 1.65 (1.04–2.63) | |||

| Social Support | <0.001 | 0.094 | ||||||

| Familial | 18.3 | 1 | 31.9 | 1 | ||||

| None | 29.4 | 1.86 (0.64–5.42) | 0.258 | 54.5 | 2.56 (1.07–6.14) | 0.035 | ||

| Yes, but not familial | 55.6 | 5.57 (2.13–14.57) | <0.001 | 33.3 | 1.07 (0.39–2.93) | 0.899 | ||

| BMI Categories | 0.026 | 0.019 | ||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 26.9 | 1 | 27.9 | 1 | ||||

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 17.7 | 0.58 (0.28–1.21) | 0.149 | 27.8 | 0.99 (0.50–1.95) | 0.981 | ||

| 30–34 kg/m2 | 16.0 | 0.52 (0.25–1.09) | 0.084 | 37.0 | 1.51 (0.77–2.98) | 0.232 | ||

| 35–40 kg/m2 | 24.2 | 0.87 (0.37–2.02) | 0.739 | 30.0 | 1.11 (0.47–2.61) | 0.819 | ||

| >40 kg/m2 | 42.9 | 2.04 (0.71–5.87) | 0.188 | 57.6 | 3.50 (1.47–8.36) | <0.001 | ||

| Alcohol | 0.011 | 0.777 | ||||||

| Teetotal | 8.9 | 1 | 33.9 | 1 | ||||

| Heavy drinker | 28.1 | 2.07 (1.19–3.58) | 0.010 | 40.0 | 1.30 (0.45–3.78) | 0.633 | ||

| Drinker, but not risky | 23.4 | 2.64 (1.26–5.52) | 0.010 | 31.4 | 0.89 (0.54–1.47) | 0.653 | ||

| Microalbuminuria | <0.001 | 0.345 | ||||||

| No | 17.4 | 1 | 34.2 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 36.9 | 2.77 (1.57–4.89) | <0.001 | 25.8 | 0.67 (0.29–1.55) | 0.348 | ||

| CKD | 0.009 | 0.014 | ||||||

| No | 18.6 | 1 | 31.6 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 35.7 | 2.42 (1.23–4.78) | 0.010 | 51.4 | 2.32 (1.17–4.62) | 0.017 | ||

| Retinopathy | 0.006 | 0.318 | ||||||

| No | 18.4 | 1 | 32.7 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 35.4 | 2.13 (1.28–4.62) | 0.007 | 42.3 | 1.51 (0.67–3.40) | 0.321 | ||

| Neuropathy | 0.003 | 0.245 | ||||||

| No | 18.7 | 1 | 32.6 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 40.6 | 2.98 (1.41–6.29) | 0.004 | 44.0 | 1.63 (0.71–3.70) | 0.248 | ||

| CVD | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||

| No | 15.3 | 1 | 30.1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 36.1 | 3.14 (1.92–5.12) | <0.001 | 53.1 | 2.62 (1.41–4.84) | <0.01 | ||

| Atrial Fibrillation | 0.269 | 0.013 | ||||||

| No | 19.6 | 1 | 31.4 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 26.8 | 1.51 (0.73–3.14) | 0.272 | 53.1 | 2.48 (1.19–5.16) | 0.016 | ||

| Respiratory Diseases | 0.026 | 0.052 | ||||||

| No | 18.4 | 1 | 31.0 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 29.7 | 1.88 (1.07–3.30) | 0.028 | 43.8 | 1.73 (0.99–3.01) | 0.054 | ||

| Psychotic Disorders | 0.010 | 0.051 | ||||||

| No | 19.3 | 1 | 32.0 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 46.7 | 3.65 (1.29–10.36) | 0.015 | 52.0 | 2.31 (1.02–5.23) | 0.046 | ||

| Mood Disorders | <0.001 | 0.007 | ||||||

| No | 16.5 | 1 | 27.7 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 39.5 | 3.10 (1.83–5.27) | <0.001 | 41.7 | 1.87 (1.18–2.95) | <0.01 | ||

| Cancer | 0.078 | 0.009 | ||||||

| No | 189 | 1 | 31.4 | 1 | 31.4 | |||

| Yes | 28.8 | 1.73 (0.94–3.21) | 0.081 | 55.2 | 2.69 (1.25–5.80) | 55.2 | ||

| DPP-4 Inhibitors | 0.032 | 0.135 | ||||||

| Never | 18.5 | 1 | 30.8 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 42.9 | 2.45 (1.23–4.87) | 0.011 | 38.5 | 1.40 (0.61–3.22) | 0.426 | ||

| Yes, currently | 19.4 | 1.06 (0.55–2.06) | 0.862 | 44.9 | 1.83 (0.98–3.40) | 0.057 | ||

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | 0.001 | 0.738 | ||||||

| Never | 18.5 | 1 | 32.3 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 48.3 | 4.12 (1.88–9.01) | <0.001 | 38.5 | 1.31 (0.42–4.12) | 0.644 | ||

| Yes, currently | 17.9 | 0.96 (0.55–1.68) | 0.885 | 36.5 | 1.21 (0.70–2.07) | 0.500 | ||

| Insulin | 0.014 | 0.899 | ||||||

| Never | 17.7 | 1 | 33.6 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 23.5 | 1.43 (0.62–3.31) | 0.400 | 35.7 | 1.10 (0.49–2.48) | 0.819 | ||

| Yes, currently | 33.9 | 2.39 (1.31–4.36) | 0.005 | 30.0 | 0.86 (0.39–1.88) | 0.706 | ||

| Antihypertensive Therapies, ACEIs/ARBs | <0.001 | 0.062 | ||||||

| Never | 16.5 | 1 | 28.9 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 45.9 | 4.30 (2.04–9.05) | <0.001 | 55.6 | 3.08 (1.14–8.33) | 0.027 | ||

| Yes, currently | 19.3 | 1.21 (0.74–2.00) | 0.451 | 35.1 | 1.33 (0.83–2.13) | 0.235 | ||

| Antihypertensive Therapies, Non-ACEIs/ARBs | 0.007 | 0.080 | ||||||

| Never | 17.0 | 1 | 0.002 | 29.9 | 1 | |||

| Yes, but not currently | 6.3 | 2.65 (1.10–4.99) | 0.238 | 46.4 | 2.03 (0.92–4.48) | 0.080 | ||

| Yes, currently | 22.5 | 1.42 (0.79–2.52) | 40.6 | 1.60 (0.92–2.78) | 0.096 | |||

| Antiplatelet Drugs | 0.001 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Never | 16.0 | 1 | 29.5 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 29.0 | 2.15 (0.94–4.94) | 0.070 | 52.2 | 2.60 (1.10–6.13) | 0.029 | ||

| Yes, currently | 32.6 | 2.55 (1.51–4.31) | <0.001 | 51.4 | 2.52 (1.26–5.04) | 0.009 | ||

| Psychiatric Drugs | <0.001 | 0.508 | ||||||

| Never | 18.0 | 1 | 32.7 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 34.6 | 2.42 (1.04–5.64) | 0.041 | 50.0 | 2.06 (0.56–8.39) | 0.314 | ||

| Yes, currently | 52.9 | 5.14 (1.92–13.76) | 0.001 | 40.0 | 1.37 (0.48–3.96) | 0.559 | ||

| Mood Disorder Drugs | 0.044 | 0.092 | ||||||

| Never | 19.0 | 1 | 30.3 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 16.0 | 0.81 (0.27–2.43) | 0.707 | 33.3 | 1.15 (0.49–2.68) | 0.748 | ||

| Yes, currently | 36.1 | 2.40 (1.16–4.96) | 0.018 | 44.3 | 1.83 (1.06–3.15) | 0.030 | ||

| Analgesics | 0.014 | 0.102 | ||||||

| Never | 26.2 | 1 | 30.0 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 15.4 | 0.52 (0.27–0.99) | 0.045 | 26.8 | 0.86 (0.36–2.06) | 0.727 | ||

| Yes, currently | 26.7 | 1.02 (0.52–2.02) | 933 | 38.3 | 1.45 (0.63–3.34) | 0.384 | ||

| Corticosteroids | 0.758 | 0.031 | ||||||

| Never | 19.8 | 1 | 30.2 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 19.8 | 1.00 (0.54–1.83) | 0.989 | 34.3 | 1.21 (0.73–2.00) | 0.467 | ||

| Yes, currently | 35.0 | 1.35 (0.61–3.00) | 0.464 | 55.6 | 2.89 (1.28–6.50) | 0.011 | ||

| Anticancer Medication | 0.003 | 0.099 | ||||||

| Never | 18.7 | 1 | 31.4 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 11.1 | 0.54 (0.12–2.41) | 0.423 | 38.5 | 1.36 (0.42–4.28) | 0.595 | ||

| Yes, currently | 85.3 | 3.11 (1.53–6.31) | 0.002 | 50.0 | 2.18 (1.05–4.55) | 0.037 | ||

| Immunomodulators | 0.001 | 0.176 | ||||||

| Never | 17.7 | 1 | 32.0 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 42.9 | 3.50 (1.42–8.61) | 0.006 | 33.3 | 1.06 (0.19–5.89) | 0.946 | ||

| Yes, currently | 37.5 | 2.80 (1.31–5.98) | 0.008 | 50.0 | 2.12 (0.95–4.75) | 0.067 | ||

| Sulfonylureas | <0.01 | 0.024 | ||||||

| Never | 18.0 | 1 | 31.4 | 1 | ||||

| Yes, but not currently | 41.0 | 3.17 (1.59–6.30) | 0.001 | 57.7 | 2.97 (1.32–6.72) | <0.01 | ||

| Yes, currently | 25.0 | 1.52 (0.48–4.84) | 0.480 | 31.3 | 0.99 (0.34–2.93) | 0.987 | ||

| Polypharmacy | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 13.8 | 1 | 43.4 | 2.43 (1.53–3.86) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 28.7 | 2.51 (1.57–4.01) | <0.001 | 24.0 | 1 | |||

| Mediterranean Diet | 0.087 | 0.095 | ||||||

| High adherence, ≥11 | 18.4 | 1 | 23.4 | 1 | ||||

| Medium adherence, 6–10 | 19.0 | 1.04 (0.58–1.87) | 0.894 | 36.7 | 1.90 (1.06–3.42) | 0.032 | ||

| Low adherence, 0–5 | 32.6 | 2.15 (0.97–4.79) | 0.061 | 31.3 | 1.49 (0.46–4.86) | 0.508 | ||

| Physical Activity | 0.001 | 0.008 | ||||||

| Moderate or high | 14.5 | 1 | 25.8 | 1 | ||||

| Low | 27.1 | 2.18 (1.37–3.49) | 0.001 | 39.5 | 1.87 (1.18–2.99) | <0.01 | ||

| Men (n = 445) | Women (n = 341) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age Group | ||||

| >75 years | 1 | 1 | ||

| 61–75 years | 2.22 (0.67–7.33) | 0.189 | 0.78 (0.39–1.59) | 0.493 |

| <60 years | 4.30 (1.31–14.11) | 0.016 | 0.75 (0.35–1.60) | 0.456 |

| Social Support | ||||

| Familial | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes, but no familial | 7.96 (2.10–30.11) | 0.002 | 1.43 (0.46–4.46) | 0.542 |

| None | 1.15 (0.30–4.44) | 0.843 | 1.98 (0.70–5.60) | 0.196 |

| BMI Categories | ||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 0.61 (0.23–1.64) | 0.325 | 0.82 (0.37–1.84) | 0.636 |

| 30–34 kg/m2 | 0.43 (0.16–1.18) | 0.102 | 1.37 (0.60–3.12) | 0.451 |

| 35–40 kg/m2 | 0.71 (0.24–2.12) | 0.538 | 1.15 (0.42–3.14) | 0.780 |

| >40 kg/m2 | 1.35 (0.36–5.02) | 0.654 | 4.10 (1.50–11.18) | 0.006 |

| Cancer | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.64 (0.20–2.05) | 0.452 | 5.05 (1.51–16.86) | 0.009 |

| Mood Disorders | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.73 (1.13–6.64) | 0.026 | 1.81 (0.94–3.50) | 0.077 |

| Antihypertensive Therapies, ACEIs/ARBs | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes, but not currently | 3.24 (1.05–10.04) | 0.041 | 0.66 (0.17–2.55) | 0.551 |

| Yes, currently | 0.96 (0.47–1.96) | 0.779 | 0.85 (0.44–1.65) | 0.635 |

| Antiplatelet Drugs | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes, but not currently | 1.11 (0.28–4.42) | 0.879 | 2.06 (0.61–6.98) | 0.246 |

| Yes, currently | 1.13 (0.39–3.25) | 0.818 | 3.16 (1.16–8.64) | 0.025 |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Moderate or high | 1 | 1 | ||

| Low | 3.34 (1.80–6.20) | <0.001 | 1.66 (0.94–2.92) | 0.082 |

| Mediterranean Diet | ||||

| High adherence, ≥11 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Medium adherence, 6–10 | 1.01 (0.49–2.09) | 0.985 | 1.45 (0.74–2.85) | 0.278 |

| Low adherence, 0–5 | 1.93 (0.72–5.18) | 0.192 | 0.72 (0.17–2.95) | 0.645 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vich-Pérez, P.; Taulero-Escalera, B.; Regueiro-Toribio, P.; Prieto-Checa, I.; García-Espinosa, V.; Villanova-Cuadra, L.; Sevilla-Machuca, I.; Timoner-García, J.; Martínez-Grandmontagne, M.; Abós-Pueyo, T.; et al. Self-Perceived Health Status of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in Spain: Associated Factors and Sex Differences. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196770

Vich-Pérez P, Taulero-Escalera B, Regueiro-Toribio P, Prieto-Checa I, García-Espinosa V, Villanova-Cuadra L, Sevilla-Machuca I, Timoner-García J, Martínez-Grandmontagne M, Abós-Pueyo T, et al. Self-Perceived Health Status of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in Spain: Associated Factors and Sex Differences. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196770

Chicago/Turabian StyleVich-Pérez, Pilar, Belén Taulero-Escalera, Paula Regueiro-Toribio, Isabel Prieto-Checa, Victoria García-Espinosa, Laura Villanova-Cuadra, Ignacio Sevilla-Machuca, Julia Timoner-García, Mario Martínez-Grandmontagne, Tania Abós-Pueyo, and et al. 2025. "Self-Perceived Health Status of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in Spain: Associated Factors and Sex Differences" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196770

APA StyleVich-Pérez, P., Taulero-Escalera, B., Regueiro-Toribio, P., Prieto-Checa, I., García-Espinosa, V., Villanova-Cuadra, L., Sevilla-Machuca, I., Timoner-García, J., Martínez-Grandmontagne, M., Abós-Pueyo, T., Álvarez-Hernández-Cañizares, C., Reviriego-Jaén, G., Serrano-López-Hazas, A., Gala-Molina, I., Sanz-Pascual, M., Guereña-Tomás, M. J., González-González, A. I., Salinero-Fort, M. A., & on behalf of the LADA-PC Consortium. (2025). Self-Perceived Health Status of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in Spain: Associated Factors and Sex Differences. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196770