Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis: A Real-Life Effectiveness Study Across Multiple Belgian Centers (SULTAN)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Inclusion and Study Design

2.2. Data Collection and Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethical Statement

2.5. Data Availability Statement

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Effectiveness of Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis

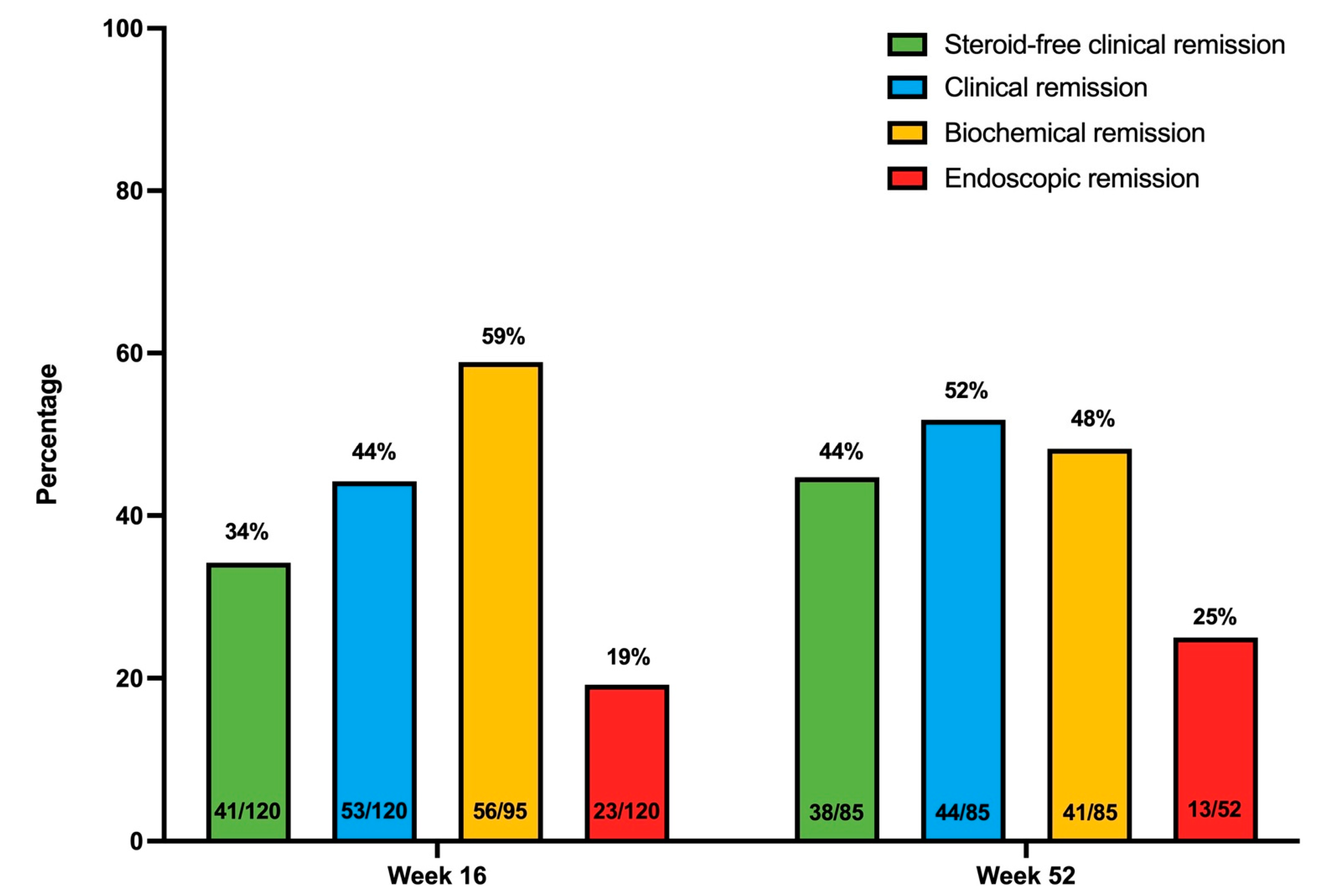

3.2.1. Clinical Remission and Response

3.2.2. Biochemical Outcomes

3.2.3. Endoscopic Outcomes

3.2.4. Histological Outcomes

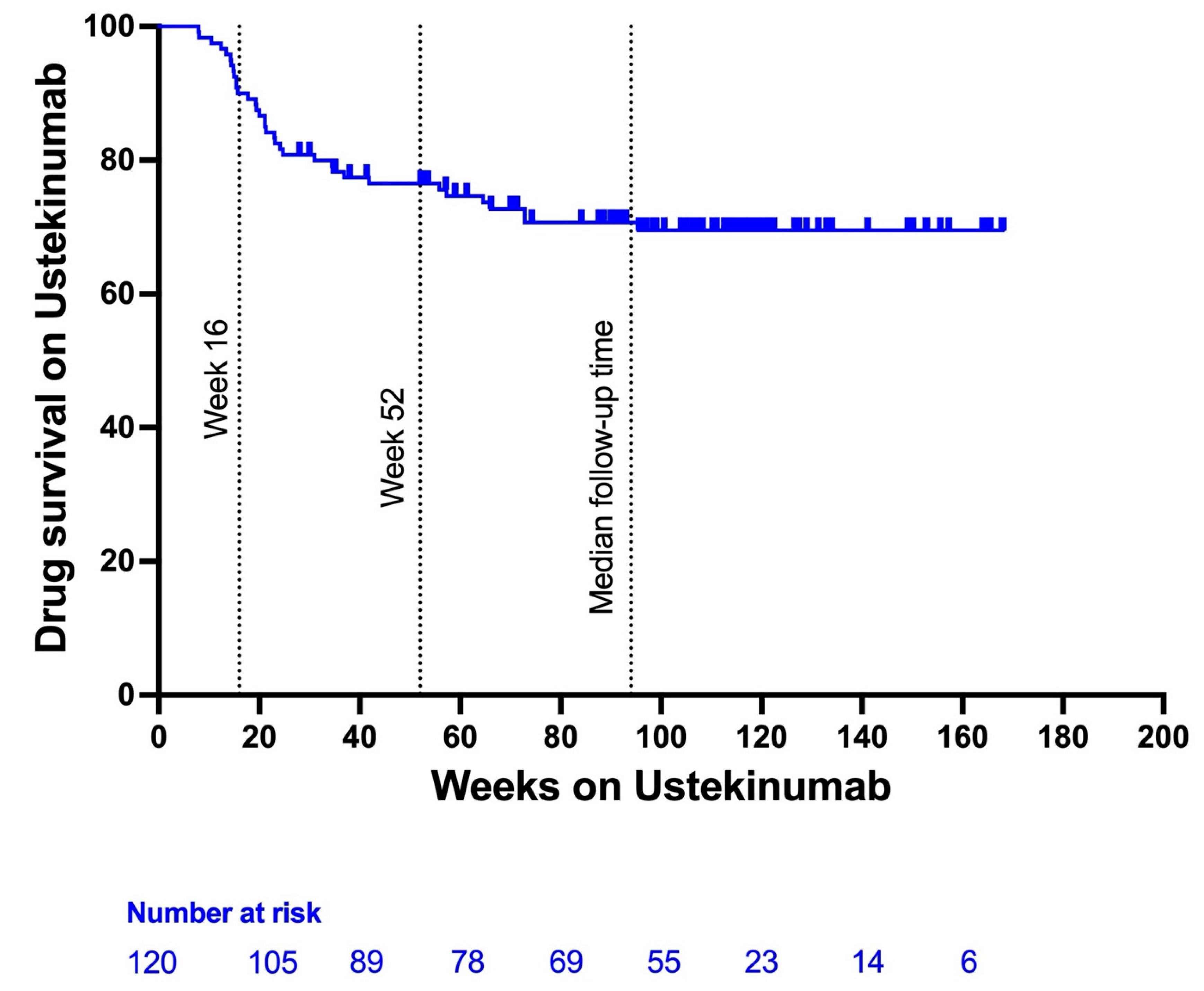

3.3. Ustekinumab Persistence and Need for Dose Optimization

3.4. Effect on Pouchitis

3.5. Effect on Extra-Intestinal Manifestations and Concurrent Immune Mediated Inflammatory Diseases

3.6. Safety of Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5ASA | 5-Aminosalicylic Acid |

| aOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IL | Interleukin |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

| UST | Ustekinumab |

References

- Lamb, C.A.; Kennedy, N.A.; Raine, T.; Hendy, P.A.; Smith, P.J.; Limdi, J.K.; Hayee, B.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Parkes, G.C.; Selinger, C.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019, 68, s1–s106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.H.; Lee, K.-M.; Kim, D.B.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.; Jeen, Y.T.; Kim, T.-O.; Kim, J.S.; Park, J.J.; Hong, S.N.; et al. Quality of Life in Newly Diagnosed Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis: Changes in the MOSAIK Cohort Over 1 Year. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armuzzi, A.; Liguori, G. Quality of life in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and the impact of treatment: A narrative review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibing, S.; Cho, J.H.; Böttinger, E.P.; Ungaro, R.C. Second–Line Biologic Therapy Following Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonist Failure: A Real–World Propensity Score–Weighted Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2629–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieujean, S.; Louis, E.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. A critical review of ustekinumab for the treatment of active ulcerative colitis in adults. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 17, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, B.E.; Sandborn, W.J.; Panaccione, R.; O’Brien, C.D.; Zhang, H.; Johanns, J.; Adedokun, O.J.; Li, K.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Van Assche, G.; et al. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, M.T.; Rowbotham, D.S.; Danese, S.; Sandborn, W.J.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tikhonov, I.; Panaccione, R.; Hisamatsu, T.; Scherl, E.J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Maintenance Ustekinumab for Ulcerative Colitis Through 3 Years: UNIFI Long-term Extension. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; Sands, B.E.; Abreu, M.T.; O’Brien, C.D.; Bravatà, I.; Nazar, M.; Miao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rowbotham, D.; Leong, R.W.L.; et al. Early Symptomatic Improvement After Ustekinumab Therapy in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: 16-Week Data From the UNIFI Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2858–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonera, C.; Olivares, D.; López-García, O.N.; Alba, C. Meta-analysis: Real-world effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 57, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Parody-Rúa, E.; Chaparro, M. Efficacy, Effectiveness, and Safety of Ustekinumab for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumery, M.; Filippi, J.; Abitbol, V.; Biron, A.; Laharie, D.; Serrero, M.; Altwegg, R.; Bouhnik, Y.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Gilletta, C.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab maintenance therapy in 103 patients with ulcerative colitis: A GETAID cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Cleveland, N.K.; Akiyama, S.; Zullow, S.; Yi, Y.; Shaffer, S.R.; Malter, L.B.; Axelrad, J.E.; Chang, S.; Hudesman, D.P.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab for Ulcerative Colitis From 2 Tertiary IBD Centers in the United States. Crohn’s Colitis 360 2021, 3, otab002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta, M.F.; Viola, A.; Mastronardi, M.; Turchini, L.; Carparelli, S.; Orlando, A.; Biscaglia, G.; Miranda, A.; Guida, L.; Costantino, G.; et al. One-year effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab in ulcerative colitis: A multicenter real-world study from Italy. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2021, 21, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Garre, A.; Iborra, M.; Sierra-Ausín, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Fernández-Clotet, A.; de Castro, L.; Boscá-Watts, M.; Casanova, M.J.; López-García, A.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis: Real-world Evidence from the ENEIDA Registry. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 1846–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iborra, M.; Ferreiro-Iglesias, R.; Dolores, M.-A.M.; Mesonero Gismero, F.; Mínguez, A.; Porto-Silva, S.; García-Ramírez, L.; de la Filia, I.G.; Aguas, M.; Nieto-García, L.; et al. Real-world long-term effectiveness of ustekinumab in ulcerative colitis: Results from a spanish open-label cohort. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 59, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarur, A.J.; Chiorean, M.V.; Panés, J.; Jairath, V.; Zhang, J.; Rabbat, C.J.; Sandborn, W.J.; Vermeire, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Achievement of Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histological Outcomes in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Treated with Etrasimod, and Association with Faecal Calprotectin and C-reactive Protein: Results From the Phase 2 OASIS Trial. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 18, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunberg, J.; Björkqvist, O.; Hedin, C.R.H.; Forss, A.; Söderman, C.; Bergemalm, D.; The SWIBREG Study Group; Olén, O.; Hjortswang, H.; Strid, H.; et al. Ustekinumab treatment in ulcerative colitis: Real-world data from the Swedish inflammatory bowel disease quality register. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2022, 10, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, S.; Vasudevan, A.; Long, T.; Van Langenberg, D. The impact of tobacco smoking on treatment choice and efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease. Intest. Res. 2020, 19, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedokun, O.J.; Xu, Z.; Gasink, C.; Kowalski, K.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B. Population Pharmacokinetics and Exposure-Response Analyses of Ustekinumab in Patietns with Moderately to Severly Active Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Ther. 2022, 44, 1336–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedokun, O.J.; Xu, Z.; Marano, C.; O’Brien, C.; Szapary, P.; Zhang, H.; Johanns, J.; Leong, R.W.; Hisamatsu, T.; Van Assche, G.; et al. Ustekinumab Pharmacokinetics and Exposure Response in a Phase 3 Randomized Trial of patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2244–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsoud, D.; Hertogh, G.D.; Compernolle, G.; Tops, S.; Sabino, J.; Ferrante, M.; Thomas, D.; Vermeire, S.; Verstockt, B. Real-world Endoscopic and Histological Outcomes Are Correlated with Ustekinumab Exposure in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 1562–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outtier, A.; Louis, E.; Dewit, O.; Reenaers, C.; Schops, G.; Lenfant, M.; Pontus, E.; de Hertogh, G.; Verstockt, B.; Sabino, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Ustekinumab for Chronic Pouchitis: A prospective open-label multicenter study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 2468–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galan, C.D.; Truyens, M.; Peeters, H.; Mesonero Gismero, F.; Elorza, A.; Torres, P.; Vandermeulen, L.; Amezaga, A.J.; Ferreiro-Iglesias, R.; Holvoet, T.; et al. The Impact of Vedolizumab and Ustekinumab on Articular Extra-Intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Real-Life Multicentre Cohort Study. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 1676–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tímár, Á.E.; Párniczky, A.; Budai, K.A.; Hernádfői, M.V.; Kasznár, E.; Varga, P.; Hegyi, P.; Váncsa, S.; Tóth, R.; Veres, D.S.; et al. Beyond the Gut: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Advanced Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease-associated Extraintestinal Manifestations. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 18, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (years, range) | 44.5 (19–89) |

| Sex (n, %) | |

| Female | 61 (50.8%) |

| Male | 59 (49.2%) |

| Disease duration (years, range) | 11 (1–74) |

| Smoking (n, %) | |

| Current smoker | 5 (4.2%) |

| Never smoked | 81 (67.5%) |

| Former smoker | 34 (38.4%) |

| Disease extent (n, %) | |

| Proctitis (Montreal E1) | 8 (6.7%) |

| Left-sided colitis (Montreal E2) | 69 (57.5%) |

| Extensive colitis (Montreal E3) | 43 (35.8%) |

| Comorbidities (n,%) | 41 (34.2%) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 (0.8%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (3.3%) |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity | 10 (8.3%) |

| Malignancy | 10 (8.3%) |

| Colon cancer | 2 (1.6%) |

| Non-melanoma skin cancer | 3 (2.5%) |

| Other solid organ cancer | 5 (4.1%) |

| Active malignancy at start UST | 2 (1.6%) |

| Extra-intestinal manifestations (n,%) | 19 (15.8%) |

| PSC | 7 (5.8%) |

Spondylarthropathy

| 8 (6.6%) 5 (4.1%) 3 (2.5%) |

| Uveitis | 2 (1.6%) |

| Erythema nodosum | 2 (1.6%) |

| Other concurrent IMIDs | |

| Psoriasis | 12 (10.0%) |

| Hydradinitis suppurativa | 1 (0.8%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) (median, range) | 24 (14–38) |

| IBD hospitalization in previous 12 months (n, %) | 27 (22.5%) |

| IPAA (n, %) | 12 (10.0%) |

| Previous anti-TNF exposure (n, %) | 97 (80.8%) |

| Infliximab | 77 (65.0%) |

| Adalimumab | 49 (40.8%) |

| Golimumab | 14 (11.9%) |

| Previous vedolizumab use (n, %) | 81 (67.5%) |

| Previous JAK-inhibitor use (n, %) | 22 (18.3%) |

| Previous cyclosporine use (n, %) | 6 (5.0%) |

| Previous FMT (n, %) | 3 (2.5%) |

| Previous clinical trial | 18 (15.0%) |

| Failed biologicals | |

| Biological naive | 7 (5.8%) |

| 1 biological | 32 (26.7%) |

| 2 biologicals | 43 (35.8%) |

| ≥3 biologicals | 38 (31.6%) |

| Failed anti-TNF | |

| Anti-TNF naive | 23 (19.2%) |

| 1 anti-TNF failed | 59 (49.2%) |

| 2 anti-TNFs failed | 33 (27.5%) |

| 3 anti-TNFs failed | 5 (4.2%) |

| Concurrent immunomodulator use | 14 (11.9%) |

| Azathioprine | 10 (8.3%) |

| Methotrexate | 4 (3.3%) |

| Concurrent use of corticosteroids at baseline | 65 (54.2%) |

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) p-Value | OR (95% CI) p-Value | |||

| Sex (male) | 0.899 (0.463–1.745) | 0.753 | 1.380 (0.422–4.517) | 0.594 |

| Age | 0.991 (0.969–1.014) | 0.447 | 0.992 (0.958–1.026) | 0.624 |

| Disease extent | ||||

| Proctitis or left-sided colitis | Reference | Reference | ||

| Pancolitis (E3) | 1.435 (0.728–2.877) | 0.297 | 1.089 (0.379–3.132) | 0.874 |

| Smoking | 1.584 (1.032–2.430) | 0.035 | 3.058 (1.193–7.836) | 0.020 |

| Prior medical therapy | ||||

| Anti-TNF | 0.786 (0.357–1.730) | 0.549 | 2.594 (0.299–22.486) | 0.387 |

| Vedolizumab | 2.592 (1.076–6.244) | 0.034 | 1.761 (0.525–5.906) | 0.360 |

| JAK-I | 1.100 (0.480–2.519) | 0.821 | 0.885 (0.291–2.691) | 0.829 |

| Disease severity at baseline | 1.274 (0.749–2.167) | 0.372 | 2.010 (0.575–7.030) | 0.274 |

| Nancy score at baseline | 2.466 (1.068–5.695) | 0.035 | 2.305 (0.846–6.279) | 0.102 |

| Adverse Events (n, %) | |

|---|---|

| Infectious | 5 (4.2%) |

| Clostridium difficile infection | 1 (0.8%) |

| Herpes zoster | 1 (0.8%) |

| Peri-anal abscess | 1 (0.8%) |

| Candidiasis | 1 (0.8%) |

| COVID-19 infection | 1 (0.8%) |

| UC-related hospitalization | 11 (9.2%) |

| Malignancy | 2 (1.6%) |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 1 (0.8%) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 1 (0.8%) |

| Athralgia | 6 (5.0%) |

| Toxic/allergic | 4 (3.3%) |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 2 (1.6%) |

| Urticaria | 1 (0.8%) |

| Local reaction to injection | 1 (0.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holvoet, T.; Truyens, M.; Reenaers, C.; Baert, F.; Vanden Branden, S.; Cremer, A.; Pouillon, L.; Dewint, P.; Van Moerkercke, W.; Rahier, J.-F.; et al. Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis: A Real-Life Effectiveness Study Across Multiple Belgian Centers (SULTAN). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186506

Holvoet T, Truyens M, Reenaers C, Baert F, Vanden Branden S, Cremer A, Pouillon L, Dewint P, Van Moerkercke W, Rahier J-F, et al. Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis: A Real-Life Effectiveness Study Across Multiple Belgian Centers (SULTAN). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186506

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolvoet, Tom, Marie Truyens, Catherine Reenaers, Filip Baert, Stijn Vanden Branden, Anneline Cremer, Lieven Pouillon, Pieter Dewint, Wouter Van Moerkercke, Jean-François Rahier, and et al. 2025. "Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis: A Real-Life Effectiveness Study Across Multiple Belgian Centers (SULTAN)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186506

APA StyleHolvoet, T., Truyens, M., Reenaers, C., Baert, F., Vanden Branden, S., Cremer, A., Pouillon, L., Dewint, P., Van Moerkercke, W., Rahier, J.-F., Vandermeulen, L., Van Dongen, J., Peeters, H., Lambrecht, G., Vijverman, A., Van Haecke, A., Hoorens, A., & Lobaton, T. (2025). Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis: A Real-Life Effectiveness Study Across Multiple Belgian Centers (SULTAN). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186506