Abstract

Background: Iliopsoas impingement (IPI) is an increasingly recognized cause of persistent groin pain following total hip arthroplasty (THA), often resulting from mechanical conflict between the iliopsoas tendon and the anterior rim of the acetabular component. Despite its clinical relevance, risk factors contributing to IPI remain poorly defined. Methods: A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. Studies were eligible if they evaluated adult patients undergoing primary THA and reported at least one risk factor associated with IPI. Only studies with a clearly defined clinical diagnosis of IPI were included. Data extraction and risk of bias assessments were performed independently by two reviewers. Risk of bias in each study was assessed through the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Results: Twelve observational studies met the inclusion criteria. Diagnosis of IPI was based on clinical symptoms of anterior groin pain exacerbated by hip flexion; 9 studies confirmed diagnosis with anesthetic injections. Key surgical risk factors included anterior cup prominence (ORs 1.16–35.20), oversized cups (cup-to-head ratio > 1.2, OR = 5.39, or ≥6 mm difference, OR = 26.00), decreased cup inclination, collared stem protrusion (OR = 13.89), and acetabular screw protrusion > 6.4 mm. Patient-specific risk factors included female sex (ORs 2.56, 2.79), higher BMI (OR = 1.07), younger age, previous hip arthroscopy (OR = 9.60) and spinal fusion (OR = 4.60). The anterolateral approach was also associated with higher IPI risk when compared to the posterior approach (OR = 4.20). Conclusions: IPI after THA is a multifactorial complication influenced by modifiable surgical variables and patient-specific anatomy. Careful preoperative planning, precise implant positioning, and attention to individual risk factors are essential to reduce IPI incidence and improve outcomes.

Keywords:

iliopsoas muscle; impingement syndrome; hip joint; arthroplasty; replacement; hip; groin; risk factors 1. Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a widely performed procedure with rising global prevalence [1,2]. As its use expands, so does the importance of recognizing complications such as iliopsoas impingement (IPI), a frequently underdiagnosed cause of postoperative groin pain [3]. IPI typically results from mechanical irritation of the iliopsoas tendon as it passes over the anterior rim of the acetabular component [3]. The reported prevalence of IPI after THA ranges from 0.4% to 8.3% [4,5].

The iliopsoas tendon is formed by the confluence of the psoas major and iliacus muscles, which descend from the lumbar spine and iliac fossa, respectively, and merge to insert on the lesser trochanter of the femur [6,7]. As it travels anterior to the hip joint, the tendon passes directly over the iliopectineal eminence and the anterior rim of the native acetabulum [6,7].

In this scenario, the etiology of IPI following total hip arthroplasty is multifactorial, involving both patient-specific and surgical variables. Several studies have implicated factors such as excessive anterior cup prominence, reduced anteversion, oversized acetabular components, and patient-specific anatomical variations [8,9]. Additionally, different surgical approaches and implant designs may influence the risk of developing iliopsoas impingement by altering the anatomical relationship between the iliopsoas tendon and the prosthetic components [3,10]. Although relatively uncommon, IPI can lead to significant functional impairment and dissatisfaction, sometimes necessitating further interventions including corticosteroid injections, tendon release, or revision arthroplasty [11]. However, no consensus has been reached regarding which risk factors are most predictive or preventable.

This systematic review aims to synthesize the current evidence on risk factors associated with IPI following THA. Specifically, we sought to address the following research questions (RQ):

- RQ1: What surgical factors (e.g., implant positioning, approach, component design) are associated with an increased risk of iliopsoas impingement after THA?

- RQ2: What patient-specific anatomical or demographic characteristics are associated with a higher incidence of IPI?

- RQ3: How consistently are these risk factors reported across clinical studies, and what is the strength of the available evidence?

By identifying consistent predictors across the literature, we aim to inform clinical decision-making, improve surgical planning, and reduce the incidence of this challenging complication.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [12]. We searched the following electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. Additional sources included reference lists of included articles and relevant systematic reviews. All databases were last searched on the 15 April 2025. We did not search grey literature sources or preprint servers, which may have introduced publication bias by potentially excluding relevant unpublished or non-peer-reviewed studies. This systematic review was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO database (Registration ID: CRD420251121035).

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Process

The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH) and free-text terms. A sample search for PubMed included the following keywords: (iliopsoas OR psoas) AND (impingement OR tendinitis OR tendonitis OR groin pain) AND (total hip arthroplasty OR THA OR hip replacement). After removal of duplicates, two independent reviewers (M.M. and A.D.M) screened all titles and abstracts for eligibility using Rayyan (version 1.4.3, accessed on the 15 April 2025). Full texts of potentially relevant studies were then assessed independently. Prior to the screening process, a calibration exercise was conducted on a subset of studies. Inter-rater agreement between reviewers was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, demonstrating substantial agreement (κ = 0.84). Discrepancies during screening or data extraction were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (V.L). No automation tools were used in the screening process.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible if they investigated adults (aged ≥ 18 years) who underwent primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) and subsequently developed symptoms of iliopsoas impingement (IPI). To be included, studies had to report at least one risk factor or predictor associated with IPI. We considered randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, and case series with ten or more patients. Only studies published in English were included. No date restrictions were applied during the literature search; all studies published up to the 15 April 2025 were considered for inclusion regardless of publication year. Excluded were studies on revision THA, hip resurfacing, animal or cadaveric studies, case reports, narrative reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and studies lacking a clearly defined diagnosis of IPI or its associated risk factors.

2.4. Data Collection Process

Two reviewers (M.M. and V.L.) independently extracted data from all included studies using a standardized data extraction form. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. When required, study authors were contacted to clarify missing or unclear data. No automation tools were used in this process.

2.5. Data Items

The primary outcome was the presence of risk factors associated with iliopsoas impingement after THA. We also collected data on patient demographics (age, sex), surgical approach, implant type and positioning, diagnostic criteria used for IPI, and outcomes such as prevalence or treatment response. For studies with unclear variables, assumptions were minimized and only explicitly reported data were extracted.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias was assessed independently by two reviewers (M.M. and V.L.). For observational studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate selection, comparability, and outcome domains. Randomized trials, if included, were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool (Cochrane, London, UK). Agreement between reviewers was excellent, with a Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of 0.91, indicating near-perfect inter-rater reliability. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. No automation tools were used.

2.7. Effect Measures

Effect measures used to quantify associations between risk factors and IPI included odds ratios (ORs), relative risks (RRs), and hazard ratios (HRs), as reported in individual studies. Where available, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also extracted.

2.8. Synthesis Methods

A qualitative synthesis was conducted to summarize identified risk factors. When studies provided sufficient and comparable data, we planned to conduct a random-effects meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and Chi-square test. If meta-analyses were feasible, results would be presented using forest plots. Data were synthesized by study design and population characteristics to preserve clinical and methodological consistency.

3. Results

3.1. Studies Characteristics

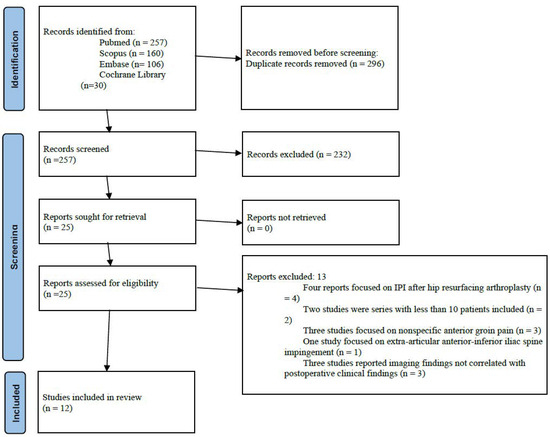

The initial search yielded a total of 257 potentially relevant articles after duplicates removal. After title and abstract selection, 232 articles were excluded. Four additional articles were excluded after full-text assessment: these studies included data on patients developing IPI after hip resurfacing. Two studies were excluded since these were case series with less than ten patients included. Three studies were excluded because they did not specifically assess iliopsoas tendinopathy, but rather included a broader population of patients with anterior groin pain of unspecified etiology. One study was excluded since it focused on extra-articular anterior-inferior iliac spine impingement. Three studies were excluded because they reported imaging findings suggestive of iliopsoas impingement but did not correlate these findings with postoperative clinical symptoms. Finally, 12 studies were analyzed [4,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] (Figure 1). Publication year ranged from 2014 to 2024. Nine studies were level of evidence III and three studies were level of evidence IV. Since all the included studies were observational studies, risk of bias in each study was assessed through the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: eight studies achieved the maximum score of 9 stars, and the remaining four scored 8 stars, indicating low risk of bias and strong overall study quality (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the selection process according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020 guidelines.

Table 1.

Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale for cohort studies (★ = 1 point; ★★ = 2 points according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale scoring system).

3.2. Patients Characteristics

Patient populations ranged from 23 to 1815 subjects per study. The number of hips in the included studies ranges from 23 to 2120. Mean age was reported in 10 studies [4,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,23] and ranged from 37.4 to 68.8 years. Mean follow-up was reported in 8 studies [4,13,14,18,19,21,22,23] and ranged from 24.2 to 55.9 months. Mean BMI was reported in 9 studies [4,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,23] and ranged from 23.2 to 28.1 kg/m2. Surgical approach was reported in 11 studies (for a total of 6108 hips) [4,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,23]: posterolateral approach was chosen for 1107 hips (18.1%), direct anterior for 2899 THAs (47.5%), anterolateral for 2102 hips (34.4%). Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patients’ characteristics (/ = no data available).

3.3. Diagnosis of Iliopsoas Impingement

In all the included studies, the diagnosis of iliopsoas impingement was based on clinical criteria, namely the presence of anterior groin pain exacerbated by active hip flexion (Table 3). However, diagnostic confirmation methods varied across the included studies. In nine of the included studies [4,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21], the diagnosis of iliopsoas impingement was further supported by the use of local anesthetic injections, with symptomatic relief considered confirmatory. One study employed imaging findings (ultrasound and MRI) to confirm iliopsoas tendinopathy or iliopectineal bursitis [19]. The prevalence of iliopsoas impingement was reported in 11 studies [4,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] and was reported to range from 1.5% to 11%.

Table 3.

Main findings and Risk factor for Ilepsoas Impingement (IPI) (/ = no data available).

3.4. Risk Factors

3.4.1. Surgical Factors

Anterior cup prominence or cup overhang was identified to be significantly associated with iliopsoas impingement [13,16,18,19,20,21,23]:

- Buller et al. [13] found any measurable anterior cup overhang on the false profile to be significantly associated with IPI, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 7.07 (95% CI 2.52–19.78; p < 0.001);

- accordingly, Park et al. [4] reported an aOR of 15.43 for antero-inferior cup prominence > 8 mm on lateral radiographs (95% CI 3.75–63.47; p = 0.002);

- Kobayashi et al. [18] observed sagittal and axial anterior cup protrusion to be significantly associated with symptomatic IPI, with an aOR of 1.77 (95% CI 1.29–2.41; p < 0.001) and 1.16 (95% CI 1.03–1.29; p = 0.007), respectively;

- similarly, Ueno et al. [20] recorded that an axial protrusion length of 12 mm (aOR, 17.13; 95% CI, 2.78–105.46; p = 0.002) and a sagittal protrusion length of 4 mm (aOR, 8.23; 95% CI, 1.44–46.94; p = 0.018) were independent predictors of symptomatic IPI;

- anterior cup protrusion was observed to be significantly associated with iliopsoas impingement by Marth et al. [21] (OR 35.20, 95% CI 10.53–117.73; p < 0.001), Zhu et al. [19] (p < 0.001), Hardwick-Morris et al. [16] (>6.5 mm, p = 0.024) and Tamaki et al. [23] (p = 0.001).

Oversized cups were also associated with IPI:

- Odri et al. [22] showed that a difference between implanted and native femoral head diameter ≥6 mm was significantly associated with IPI (aOR 26.00; 95% CI 6.30–108.00, p < 0.01);

- Kobayashi et al. [18] observed oversized cups to be associated with symptomatic iliopsoas impingement (aOR 1.26; 95% CI 0.89–1.66, p = 0.192).

Accordingly, Buller et al. [13] reported that a cup-to-head ratio >1.2 significantly increased the risk of developing iliopsoas impingement (aOR 5.39; p < 0.05).

As regards cup positioning, Odri et al. found significantly lower inclination angles in symptomatic patients (p = 0.03). With regard to acetabular screw positioning, Ueki et al. found that screw protrusion >6.4 mm was associated with iliopsoas tendinopathy and poorer outcomes (p < 0.001) [15]. Similarly, Zhu et al. [19] observed protruded acetabular screws to be associated with IPI (p < 0.001).

Ueno et al. reported that the anterolateral approach was associated with a significantly higher risk of IPI compared to the posterior approach (aOR 4.20, 95% CI 1.68–10.49, p = 0.002) [20].

Excessive stem anteversion (aOR 1.75, 95% CI 1.25–2.43, p = 0.001) and collar protrusion (aOR 13.89, 95% CI 3.14–62.50, p = 0.001) were identified to be independent predictors for IPI after cementless collared THA by Qiu et al. [15]. Moreover, patients with Dorr type C bone appeared to be at higher risk of developing IPI after cementless collared THA [15].

Leg lengthening was observed to be significantly associated with iliopsoas impingement by Park et al. [4] (OR 1.06, CI 1.03–1.11, p = 0.018) and by Zhu et al. [19] (p < 0.001).

3.4.2. Patient-Related Factors

Several studies identified patient-specific characteristics that independently predicted IPI. Female sex was associated with higher IPI risk in multivariable analyses by Park et al. [19] (aOR 2.56; 95% CI 1.36–4.82; p = 0.012) and Buller et al. [13] (aOR 2.79; 95% CI 1.18–6.56 p = 0.020). Higher body mass index (BMI) was also found to be a significant predictor by Park et al. [19], with an aOR of 1.14 per unit increase (95% CI 1.07–1.21; p < 0.001). Verhaegen et al. [14] reported younger age (p < 0.001), history of spinal fusion (aOR 4.6; 95% CI 1.60–13.40, p = 0.016) and previous hip arthroscopy (OR 9.60, 95% CI 2.60–34.30, p = 0.002) to be significantly associated with increased IPI risk. Preoperative and postoperative hip flexion angles were observed to be significantly greater in patients with symptomatic IPI (p = 0.013 and p = 0.006, respectively) by Tamaki et al. [23]. Risk factors are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 4.

Effect size of risk factor for Iliopsoas Impingement (IPI) (/ = no data available).

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to identify and synthesize reported risk factors for iliopsoas impingement (IPI) following total hip arthroplasty (THA). Across the 12 included studies, several consistent and clinically relevant predictors were identified. These include modifiable surgical factors such as anterior cup prominence, oversized acetabular components, decreased cup inclination, acetabular screw protrusion and excessive leg lengthening, as well as patient-specific factors including higher body mass index (BMI), female sex, younger age, history of spinal fusion, and spinopelvic anatomy. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to comprehensively evaluate both surgical and anatomical risk factors for IPI using exclusively clinical cases of post-THA groin pain with clearly defined diagnostic criteria. As such, direct comparisons with prior systematic reviews are not feasible. Nevertheless, our findings align with individual observational studies that have reported significant associations between surgical variables and patient-specific factors and the risk of developing IPI.

Implant positioning was among the most frequently implicated surgical factors. Anterior cup prominence or overhang emerged as the most consistently reported risk factor for IPI across the included studies [13,16,18,19,20,21,23]. This finding is biomechanically intuitive: a protruding cup rim increases the likelihood of mechanical conflict with the iliopsoas tendon during hip flexion, especially in deep flexion or stair climbing. The iliopsoas works as the principal dynamic hip flexor, functioning within a pulley system comprising the anterior border of the acetabulum and gliding over the iliopectineal eminence and adjacent anterior structures during movement [6,7,11]. Indeed, oversizing of the acetabular component, particularly with a cup-to-native head size ratio >1.2 or an absolute difference ≥6 mm, was also associated with increased impingement risk [13,22]. Then, anterior overreaming during surgery can lead to an anterior wall defect and increased cup protrusion, causing symptomatic IPI [18,24]. Additionally, reduced cup inclination and anteversion can increase the risk of protrusion of the acetabular component, thus were identified as contributors to IPI [16,25]. These results support the principle that restoring native femoral head geometry and hip center of rotation and avoiding overstuffing the anterior hip space are crucial for minimizing soft tissue conflict. Biomechanical cadaveric studies have confirmed that anterior cup protrusion, decreased stem anteversion, and increased offset directly elevate iliopsoas surface pressure, particularly during hip extension [26]. Malpositioned components can alter the spatial relationship between the prosthetic cup and the overlying iliopsoas tendon, increasing mechanical friction. Zhu et al. suggested that excessive anteversion could be associated with higher rates of IPI [19]. High combined functional anteversion may cause the iliopsoas to function as an anterior stabilizer to the prosthetic joint causing overuse and irritation, or may lead to posterior prosthetic impingement that irritates the iliopsoas through repeated anterior micro-instability [13,19,27]. Indeed, the iliopsoas serves to reinforce the anterior capsule ligaments as the hip is extended [28].

Protruding acetabular screws (>6.4 mm) were identified by both Ueki et al. [15] and Zhu et al. [19] as mechanical contributors to IPI, highlighting the importance of screw trajectory and intraoperative verification of screw length whenever supplemental screws are used to enhance the initial fixation of cementless acetabular cups. This could be particularly relevant in dysplastic hips, where the inherent bone deficiency and surgical necessity for initial cup fixation with screws can lead to a higher frequency of protruded screws [19]. However, Zhu et al. [19] did not observe a higher incidence of postoperative iliopsoas tendonitis in the dysplastic hips group. Thus, even subtle technical decisions during surgery may have significant clinical consequences in the development of IPI. In this scenario, Verhaegen et al. also reported a higher incidence of psoas-related pain in patients with ceramic-on-ceramic (CoC) bearing surfaces compared to ceramic-on-polyethylene (CoP) [14]. However, the sources clarify that this observed association appears to be an indirect one, linked to patient selection criteria rather than a direct causal mechanism of the ceramic bearing itself, since the study found a strong correlation between younger age and CoC bearing [14].

Surgical approach has been shown to influence the risk of iliopsoas impingement (IPI) after total hip arthroplasty. In particular, Ueno et al. [20] found the anterolateral surgical approach to be associated with a significantly higher risk of IPI compared to the posterior approach. This could be secondary to anterior capsule disruption during capsulotomy, which removes a protective layer that normally separates the iliopsoas complex from the acetabular component: when this layer is compromised, the iliopsoas tendon can come into direct contact with the acetabular component, potentially leading to mechanical irritation [13,21]. Dora et al. described how during arthroscopic iliopsoas tenotomy the iliopsoas tendon could be visualized directly through a defect in the anterior neocapsule, where the anterior rim of the acetabular cup was exposed [26]. Moreover, a less anteverted acetabular component might be favored in anterior approaches for stability benefits [29,30].

Several studies examined the role of femoral component design and positioning. Qiu et al. [17] identified excessive stem anteversion, collar protrusion, and Dorr type C femurs as risk factors for IPI when using cementless collared stems. Indeed, not only excessive stem anteversion could lead to anterior microinstability [13,19,27], but may also cause the collar to overhang beyond the edge of the calcar, leading to impingement on the distal segment of the iliopsoas tendon at the lesser trochanter [17]. This again underscores the relevance of combined anteversion, but also the physical profile of the implant in influencing IPI risk. In fact, Dorr type C femurs often require larger stem sizes, and an increase in stem size can be associated with increased collar length and collar protrusion, thus increasing the likelihood of impingement [17].

Patient-specific anatomical factors also played a significant role. Park et al. [19] and Verhaegen et al. [14] found that female sex, higher BMI, younger age, and spinal fusion were all associated with an increased risk of IPI. Particularly, spinal fusion may rigidify the spinopelvic segment and impair pelvic adaptability during positional changes, thereby increasing anterior impingement during hip flexion [31]. The influence of spinopelvic stiffness is supported by biomechanical studies demonstrating that restricted posterior pelvic tilt limits acetabular anteversion in sitting, forcing excessive femoral hyperflexion and increasing iliopsoas-tendon contact with anterior hardware [32,33]. Tamaki et al. [23] further observed that both pre- and postoperative hip flexion angles were significantly greater in patients with IPI, suggesting that dynamic motion demands in certain anatomical or postural configurations augment mechanical tendon stress. Instead, female sex is consistently associated with an increased propensity or risk for IPI, since women generally have smaller native acetabular diameters compared to men, resulting in differences in acetabular diameter, anteversion, and depth of the psoas valley [34,35]. In order to accommodate a larger prosthetic femoral head and yield a better head-neck ratio, the acetabulum should be reamed to a larger size and this can increase the risk of cup overfitting and lead to a greater cup-to-native femoral head ratio in women, leading to anterior component overhang [13,21]. Moreover, a higher incidence of hip dysplasia in females may contribute to a greater degree of anterior acetabular component overhang, especially if the anterior wall of the acetabulum is deficient [34,35]. Higher BMI may contribute to IPI by increasing anterior soft tissue bulk, which can reduce the space available for iliopsoas tendon excursion and elevate friction against the acetabular component [36,37,38]. Additionally, altered hip flexion mechanics and technical challenges in achieving optimal cup positioning in obese patients may further increase the risk of tendon irritation [36,37,38].

The findings of this review have direct clinical relevance for surgeons performing THA. To minimize the risk of iliopsoas impingement, careful preoperative planning and intraoperative techniques are essential. Intraoperatively, careful reaming and implant positioning are essential to avoid anterior cup overhang, particularly by ensuring the cup remains flush with or slightly recessed from the anterior native acetabular rim, thereby minimizing the risk of iliopsoas impingement. Then, oversized cups should be avoided: cup-to-native femoral head ratio should not exceed 1.2 [13], and the implanted cup diameter should not be ≥6 mm larger than the native head [22]. For acetabular screws, protrusion beyond 6.4 mm has been associated with increased risk of IPI and should be carefully checked using intraoperative fluoroscopy or depth gauges [15]. In patients with additional risk factors such as high BMI, female sex, spinal fusion, previous hip arthroscopy or abnormal spinopelvic parameters, further intraoperative adjustments may be warranted to reduce anterior impingement. These include optimizing sagittal cup orientation based on pelvic tilt [39]. From a broader perspective, this review reinforces the multifactorial etiology of IPI and the need for a patient-specific, anatomically respectful approach to THA. Particular vigilance is advised in patients undergoing anterolateral approaches, since these have been independently associated with increased IPI risk.

This review followed PRISMA guidelines and included a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases. Only studies with clinically confirmed diagnoses of IPI were included, increasing the specificity and relevance of findings. All included studies defined IPI by anterior groin pain exacerbated by hip flexion, and most employed confirmatory diagnostic injections, enhancing diagnostic consistency.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, all included studies were observational (level III or IV evidence), limiting the strength of causal inference. Second, while diagnostic criteria were largely consistent, definitions of risk factors (e.g., “cup prominence” or “oversized components”) varied between studies, limiting comparability. Third, due to heterogeneity in study designs and outcome measures, a meta-analysis was not performed. Then, some potential risk factors such as activity level, tendon morphology, or subtle anatomical variants were not addressed in the current literature. Lastly, the variability in diagnostic confirmation methods across studies could have contributed to differences in reported prevalence: studies utilizing anesthetic injections or imaging for confirmation likely provided more specific diagnoses, while those relying solely on clinical symptoms may be at greater risk of diagnostic overlap or misclassification.

Prospective studies using standardized definitions and imaging protocols are needed to validate the risk factors identified in this review. Further research should explore the interaction between spinopelvic dynamics and impingement, and assess whether surgical planning tools could reduce the incidence of IPI. Long-term studies comparing implant types and bearing surfaces may also clarify the role of hardware-related factors in IPI development.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review identified key surgical and patient-specific risk factors for iliopsoas impingement (IPI) following total hip arthroplasty (THA). Anterior cup overhang and oversized components were the most consistent surgical predictors. Patient factors such as female sex, higher BMI, younger age, and spinal fusion also increased IPI risk. The anterolateral approach was associated with a higher incidence of IPI compared to the posterior approach.

While these findings suggest important trends, they should be interpreted with caution due to heterogeneity in study designs, diagnostic criteria, and predominantly observational data. Nonetheless, the results support the need for careful preoperative planning and implant positioning tailored to individual patient anatomy and biomechanics. Future high-quality prospective studies are warranted to confirm these associations and inform evidence-based surgical recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., A.D. and F.D.R.; methodology, M.M. and M.L.; software, A.D.M. and P.Z.; validation, M.M., V.L. and M.L.; formal analysis, M.M. and M.L.; investigation, M.M., V.L. and A.D.M.; resources, M.M.; data curation, M.M., V.L. and A.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., V.L. and A.D.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., V.L. and A.D.M.; visualization, P.Z.; supervision, A.D., M.L. and F.D.R.; project administration, M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moldovan, F.; Moldovan, L. The Impact of Total Hip Arthroplasty on the Incidence of Hip Fractures in Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moldovan, F.; Moldovan, L. A Modeling Study for Hip Fracture Rates in Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Younis, Z.; Hamid, M.A.; Ravi, B.; Abdullah, F.; Al-Naseri, A.; Bitar, K. Iliopsoas Impingement After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Review of Diagnosis and Management. Cureus 2025, 17, e83391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, C.W.; Yoo, I.; Cho, K.; Jeong, S.J.; Lim, S.J.; Park, Y.S. Incidence and Risk Factors of Iliopsoas Tendinopathy After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Radiographic Analysis of 1602 Hips. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, 1621–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, B.P.; Sculco, P.K.; Sierra, R.J.; Trousdale, R.T.; Berry, D.J. Iliopsoas Impingement After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: Operative and Nonoperative Treatment Outcomes. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2017, 99, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordoni, B.; Varacallo, M.A. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Iliopsoas Muscle. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531508/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Lin, B.; Bartlett, J.; Lloyd, T.D.; Challoumas, D.; Brassett, C.; Khanduja, V. Multiple iliopsoas tendons: A cadaveric study and treatment implications for internal snapping hip syndrome. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2022, 142, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, K.K.; Tsai, T.Y.; Dimitriou, D.; Kwon, Y.M. Three-dimensional in vivo difference between native acetabular version and acetabular component version influences iliopsoas impingement after total hip arthroplasty. Int. Orthop. 2016, 40, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baujard, A.; Martinot, P.; Demondion, X.; Dartus, J.; Faure, P.A.; Girard, J.; Migaud, H. Threshold for anterior acetabular component overhang correlated with symptomatic iliopsoas impingement after total hip arthroplasty. Bone Jt. J. 2024, 106 Pt B (Suppl. A), 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrakis, A.I.; Khoshbin, A.; Joseph, A.; Lee, L.Y.; Bostrom, M.P.; Westrich, G.H.; McLawhorn, A.S. Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty Is Not Associated with a Greater Incidence of Groin Pain in Comparison with Conventional Total Hip Arthroplasty and Hip Resurfacing: A Retrospective Comparative Study. HSS J. 2020, 16 (Suppl. 2), 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Sullivan, M.; Tai, C.C.; Richards, S.; Skyrme, A.D.; Walter, W.L.; Walter, W.K. Iliopsoas tendonitis a complication after total hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2007, 22, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W65–W94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, L.T.; Menken, L.G.; Hawkins, E.J.; Bas, M.A.; Roc, G.C., Jr.; Cooper, H.J.; Rodriguez, J.A. Iliopsoas Impingement After Direct Anterior Approach Total Hip Arthroplasty: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Treatment Options. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 1772–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaegen, J.C.F.; Vandeputte, F.J.; Van den Broecke, R.; Roose, S.; Driesen, R.; Timmermans, A.; Corten, K. Risk Factors for Iliopsoas Tendinopathy After Anterior Approach Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueki, S.; Shoji, T.; Kaneta, H.; Shozen, H.; Adachi, N. Association between cup fixation screw and iliopsoas impingement after total hip arthroplasty. Clin. Biomech. 2024, 118, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick-Morris, M.; Twiggs, J.; Miles, B.; Al-Dirini, R.M.A.; Taylor, M.; Balakumar, J.; Walter, W.L. Iliopsoas tendonitis after total hip arthroplasty: An improved detection method with applications to preoperative planning. Bone Jt. Open 2023, 4, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qiu, J.; Ke, X.; Chen, S.; Zhao, L.; Wu, F.; Yang, G.; Zhang, L. Risk factors for iliopsoas impingement after total hip arthroplasty using a collared femoral prosthesis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kobayashi, K.; Tsurumoto, N.; Tsuda, S.; Shiraishi, K.; Chiba, K.; Osaki, M. The Anterior Position of the Hip Center of Rotation Is Related to Anterior Cup Protrusion Length and Symptomatic Iliopsoas Impingement in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, 2366–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Xiao, F.; Shen, C.; Peng, J.; Chen, X. Iliopsoas tendonitis following total hip replacement in highly dysplastic hips: A retrospective study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ueno, T.; Kabata, T.; Kajino, Y.; Inoue, D.; Ohmori, T.; Tsuchiya, H. Risk Factors and Cup Protrusion Thresholds for Symptomatic Iliopsoas Impingement After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 3288–3296.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marth, A.A.; Ofner, C.; Zingg, P.O.; Sutter, R. Quantifying cup overhang after total hip arthroplasty: Standardized measurement using reformatted computed tomography and association of overhang distance with iliopsoas impingement. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 4300–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Odri, G.A.; Padiolleau, G.B.; Gouin, F.T. Oversized cups as a major risk factor of postoperative pain after total hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2014, 29, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaki, Y.; Goto, T.; Wada, K.; Omichi, Y.; Hamada, D.; Sairyo, K. Increased hip flexion angle and protrusion of the anterior acetabular component can predict symptomatic iliopsoas impingement after total hip arthroplasty: A retrospective study. Hip Int. 2023, 33, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, L.; Lehnen, A.; Kalberer, F.; Meier, C.; Wahl, P. Reconstruction of the Anterior Acetabular Wall to Repair Symptomatic Defects Consecutive to Cup Malpositioning at Total Hip Arthroplasty. Arthroplast. Today 2020, 7, 260–263.e0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tamaki, Y.; Goto, T.; Iwase, J.; Wada, K.; Omichi, Y.; Hamada, D.; Tsuruo, Y.; Sairyo, K. Relationship between iliopsoas muscle surface pressure and implant alignment after total hip arthroplasty: A cadaveric study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weber, M.; Woerner, M.; Messmer, B.; Grifka, J.; Renkawitz, T. Navigation is Equal to Estimation by Eye and Palpation in Preventing Psoas Impingement in THA. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2017, 475, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jacobsen, J.S.; Hölmich, P.; Thorborg, K.; Bolvig, L.; Jakobsen, S.S.; Søballe, K.; Mechlenburg, I. Muscle-tendon-related pain in 100 patients with hip dysplasia: Prevalence and associations with self-reported hip disability and muscle strength. J. Hip Preserv. Surg. 2017, 5, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dora, C.; Houweling, M.; Koch, P.; Sierra, R.J. Iliopsoas impingement after total hip replacement: The results of non-operative management, tenotomy or acetabular revision. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2007, 89, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daines, B.K.; Dennis, D.A. The importance of acetabular component position in total hip arthroplasty. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2012, 43, e23–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, N.; Hawkins, E.; Menken, L.; Deshmukh, A.; Rathod, P.; Rodriguez, J.A. Optimum anatomic socket position and sizing for the direct anterior approach: Impingement and instability. Arthroplast. Today 2019, 5, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, C.A.; Karasavvidis, T.; Vigdorchik, J.M.; DeCook, C.A. Spinopelvic Motion: A Simplified Approach to a Complex Subject. Hip Pelvis 2024, 36, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Louette, S.; Wignall, A.; Pandit, H. Spinopelvic Relationship and Its Impact on Total Hip Arthroplasty. Arthroplast. Today 2022, 17, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haffer, H.; Adl Amini, D.; Perka, C.; Pumberger, M. The Impact of Spinopelvic Mobility on Arthroplasty: Implications for Hip and Spine Surgeons. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vandenbussche, E.; Saffarini, M.; Taillieu, F.; Mutschler, C. The asymmetric profile of the acetabulum. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.; Roh, Y.H.; Hong, J.E.; Nam, K.W. Differences in Acetabular Morphology Related to Sex and Side in South Korean Population. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobba, W.; Lawrence, K.W.; Haider, M.A.; Thomas, J.; Schwarzkopf, R.; Rozell, J.C. The influence of body mass index on patient-reported outcome measures following total hip arthroplasty: A retrospective study of 3903 Cases. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024, 144, 2889–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodt, S.; Nowack, D.; Jacob, B.; Krakow, L.; Windisch, C.; Matziolis, G. Patient Obesity Influences Pelvic Lift During Cup Insertion in Total Hip Arthroplasty Through a Lateral Transgluteal Approach in Supine Position. J. Arthroplast. 2017, 32, 2762–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scully, W.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Sodhi, N.; Sultan, A.A.; George, J.; Khlopas, A.; Muschler, G.F.; Higuera, C.A.; Mont, M.A. The effect of body mass index on 30-day complications after total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int. 2020, 30, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loppini, M.; Longo, U.G.; Caldarella, E.; Rocca, A.D.; Denaro, V.; Grappiolo, G. Femur first surgical technique: A smart non-computer-based procedure to achieve the combined anteversion in primary total hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).