Multiple Melanomas on Speckled Lentiginous Nevus: A Systematic Review and a Case Report

Abstract

1. Background

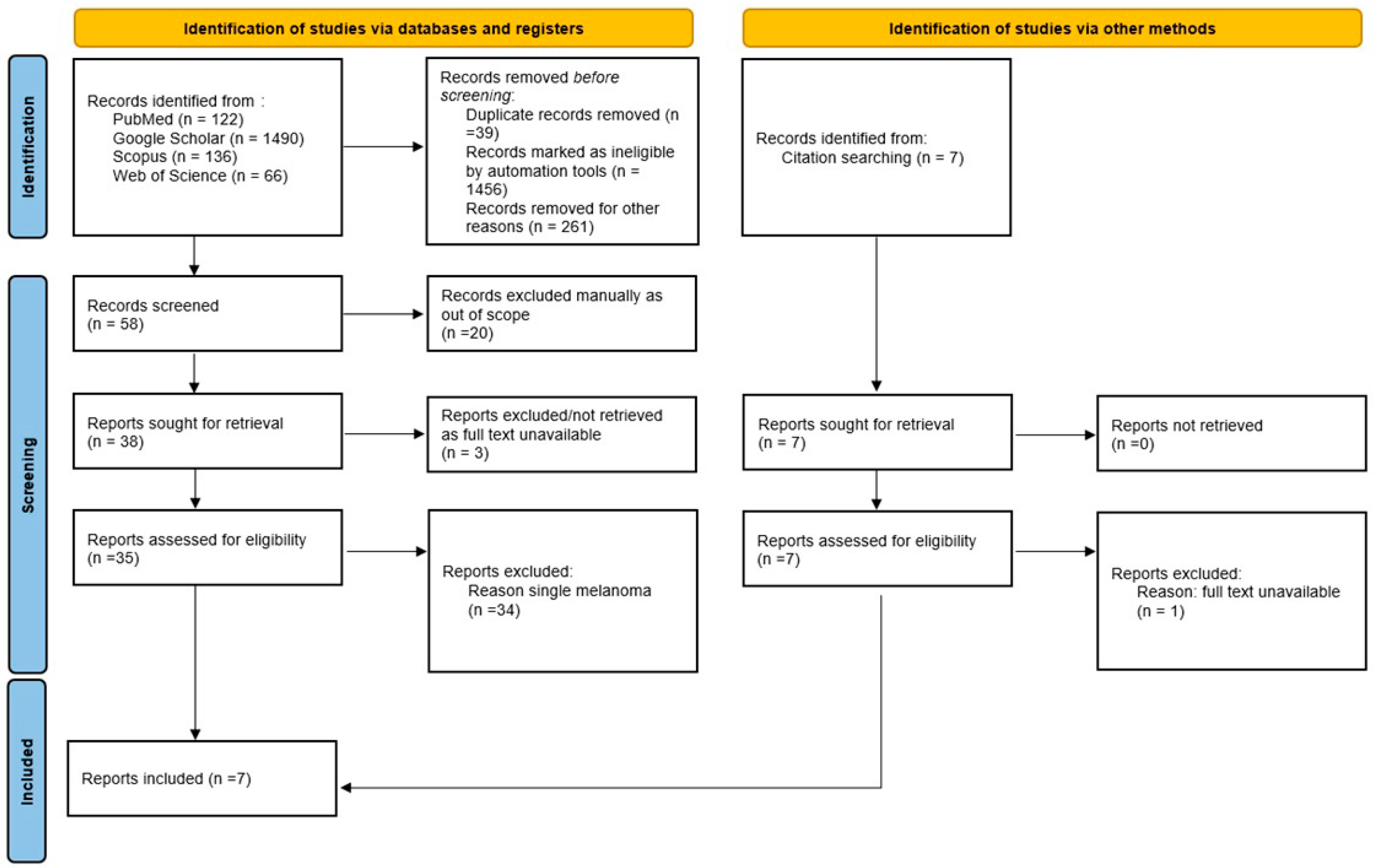

2. Methods

Information Sources and Search Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Illustrative Case Report

3.2. Systematic Review Findings

| Number | Author, Year | Patient | Features of Nevus Spilus | Features of Malignant Melanoma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age at Melanoma Diagnosis | Size of SLN | Location of SLN | Number of Melanomas | On/at Distance from SLN | Synchronous/Metachronous | Type of Melanoma | Breslow (mm) | ||

| 1 | Abecassis, 2006 [24] | M | 32 | Medium (10 cm) | Intergluteal fold | 2 | On SLN | Synchronous | Nodular | 3.5 mm |

| 32 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 1.25 mm | ||||||

| 2 | Boot-Bloemen, 2017 [30] | M | 35 | Large (over 40 cm) | Trunk, arm | 3 | At distance | Synchronous | Unspecified | 3.6 mm |

| 41 | On SLN | Metachronous | SSM | 0.65 mm | ||||||

| 41 | On SLN | Metachronous | Unspecified | 0.62 mm | ||||||

| 3 | Brito, 2017 [29] | M | 83 | Large (27 × 10 cm) | Arm, forearm | 4 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 2.51 mm |

| 83 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 1.18 mm | ||||||

| 83 | On SLN | Synchronous | Unspecified | In situ | ||||||

| 83 | At distance | Synchronous | Unspecified | In situ | ||||||

| 4 | Ly, 2011 [31] | F | 47 | Large (over 20 cm) | Lower limb and loin | 2 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 0.75 mm |

| 51 | On SLN | Metachronous | SSM | 0.70 mm | ||||||

| 5 | Ly, 2011 [31] | F | 49 | Large (over 20 cm) | Arm | 3 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | In situ |

| 49 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | In situ | ||||||

| 52 | On SLN | Metachronous | SSM | In situ | ||||||

| 6 | Meguerditchian, 2009 [28] | M | 60 | Medium (15 × 10 cm) | Leg (calf) | 2 | On SLN | Synchronous | Unspecified | 0.8 mm |

| 60 | On SLN | Synchronous | Unspecified | 0.95 mm | ||||||

| 7 | Piana, 2006 [27] | M | 28 | Medium (5 cm) | Arm | 3 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 1 mm |

| 28 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 0.7 mm | ||||||

| 28 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 0.3 mm | ||||||

| 8 | Sansoni, 2024 [18] | M | 72 | Medium (5.5 × 1.8 cm) | Trunk | 2 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | 0.3 mm |

| 72 | On SLN | Synchronous | Unspecified | In situ | ||||||

| 9 | Our case | M | 66 | Large (over 40 cm) | Trunk, arm | 3 | On SLN | Synchronous | SSM | In situ |

| 76 | On SLN | Metachronous | SSM | In situ | ||||||

| 76 | At distance | Metachronous | SSM | 0.3 mm | ||||||

4. Discussion

4.1. Patient Risk Profile

4.2. Clinical Implications and Follow-Up Strategies

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

4.5. Key Clinical Message

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| CMN | Congenital Melanocytic Nevus |

| HE | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| HMB45 | Human Melanoma Black 45 (Immunohistochemical Marker) |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| Ki-67 | Proliferation Marker Ki-67 |

| MPM | Multiple Primary Melanoma |

| NS | Nevus Spilus |

| pT1a | Pathologic Tumor Stage 1a |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCM | Reflectance Confocal Microscopy |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SLN | Speckled Lentiginous Nevus |

| SOX10 | SRY-Related HMG-box 10 (Immunohistochemical Marker) |

| SSM | Superficial Spreading Melanoma |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Zalaudek, I.; Sgambato, A.; Ferrara, G.; Argenziano, G. Diagnosis and management of melanocytic skin lesion in the pediatric praxis. A review of the literature. Minerva Pediatr. 2008, 60, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grinspan, D.; Casala, A.; Abulafia, J.; Mascotto, J.; Allevato, M. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int. J. Dermatol. 1997, 36, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, D.C.; Schwartz, R.A.; Janniger, C.K. Nevus spilus. Cutis 2007, 80, 465–468. [Google Scholar]

- Vion, B.; Belaïch, S.; Grossin, M.; Préaux, J. Developmental aspects of nevus spilus: Review of the literature apropos of 7 cases. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 1985, 112, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz, H.; Happle, R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology 2006, 212, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Deng, D. Genetic and phenotypic diversities of nevus spilus phenotypes: Case series and a proposed diagnostic algorithm. Clin. Genet. 2023, 104, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopf, A.W.; Levine, L.J.; Rigel, D.S.; Friedman, R.J.; Levenstein, M. Congenital-nevus-like nevi, nevi spili, and café-au-lait spots in patients with malignant melanoma. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1985, 11, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frings, V.G.; Goebeler, M.; Kneitz, H. Dermpath & Clinic: In situ melanoma arising within a speckled lentiginous nevus. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2018, 28, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradin, M.T.; Zattra, E.; Fiorentino, R.; Alaibac, M.; Belloni-Fortina, A. Nevus spilus and melanoma: Case report and review of the literature. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2010, 14, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanayama, H.; Terashi, H.; Hashikawa, K.; Tahara, S. Congenital melanocytic nevi and nevus spilus have a tendency to follow the lines of Blaschko: An examination of 200 cases. J. Dermatol. 2007, 34, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradia, I.; Khunger, N.; Yadav, A.K. A Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Histopathological Analysis of Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevi in Skin of Color. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Torres, K.G.; Carle, L.; Royer, M. Nevus Spilus (Speckled Lentiginous Nevus) in the Oral Cavity: Report of a Case and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2017, 39, e8–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falo, L.D., Jr.; Sober, A.J.; Barnhill, R.L. Evolution of a naevus spilus. Dermatology 1994, 189, 382–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.M.; Altman, J.; Mehregan, A.H. Speckled lentiginous nevus. Arch. Dermatol. 1978, 114, 895–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.R. Pigmented birthmarks and precursor melanocytic lesions of cutaneous melanoma identifiable in childhood. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 1983, 30, 435–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, B.; Bessis, D.; Barnéon, G.; Monpoint, S.; Guilhou, J.J. Malignant melanoma occurring on a ‘naevus on naevus’. Br. J. Dermatol. 1991, 124, 610–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkinson, N.G. Melanoma arising in a café au lait spot of neurofibromatosis. Am. J. Surg. 1957, 93, 1018–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansoni, F.; Toffoli, L.; Zacchi, A.; Agozzino, M.; Zalaudek, I.; Di Meo, N.; Pizzichetta, M.A. Synchronous Melanomas Within Nevus Spilus. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognia, J.L. Fatal melanoma arising in a zosteriform speckled lentiginous nevus. Arch. Dermatol. 1991, 127, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordeva, S.; Tchernev, G. Thin melanoma arising in nevus spilus: Dermatosurgical approach with favourable outcome. Georgian Med. News 2023, 340–341, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dessinioti, C.; Tsiakou, A.; Christodoulou, A.; Stratigos, A.J. Clinical and Dermoscopic Findings of Nevi after Photoepilation: A Review. Life 2023, 13, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, R.; Fancelli, L.; Troiano, M. Melanoma arising in giant zosteriform nevus spilus. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2012, 78, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurban, R.S.; Preffer, F.I.; Sober, A.J.; Mihm, M.C., Jr.; Barnhill, R.L. Occurrence of melanoma in “dysplastic” nevus spilus: Report of case and analysis by flow cytometry. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1992, 19, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecassis, S.; Spatz, A.; Cazeneuve, C.; Martin-Villepou, A.; Clerici, T.; Lacour, J.P.; Avril, M.F. Melanoma within naevus spilus: 5 cases. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2006, 133, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gescheidt-Shoshany, H.; Weltfriend, S.; Bergman, R. Nodular Melanoma Arising in a Large Segmental Speckled Lentiginous Nevus. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2015, 37, 663–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krähn, G.; Thoma, E.; Peter, R.U. Two superficially spreading malignant melanomas on nevus spilus. Hautarzt 1992, 43, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Piana, S.; Gelli, M.C.; Grenzi, L.; Ricci, C.; Gardini, S.; Piana, S. Multifocal melanoma arising on nevus spilus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 1380–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meguerditchian, A.N.; Cheney, R.T.; Kane, J.M., 3rd. Nevus spilus with synchronous melanomas: Case report and literature review. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2009, 13, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.H.; Dionísio, C.S.; Fernandes, C.M.; Ferreira, J.C.; Rosa, M.J.; Garcia, M.M. Synchronous melanomas arising within nevus spilus. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot-Bloemen, M.C.T.; de Kort, W.J.A.; van der Spek-Keijser, L.M.T.; Kukutsch, N.A. Melanoma in Segmental Naevus Spilus: A Case Series and Literature Review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 749–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, L.; Christie, M.; Swain, S.; Winship, I.; Kelly, J.W. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: A case series. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 64, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, C.D.; Yamada, S.; Marcassi, A.P.; Maciel, M.G.; Seize, M.P.; Cestari, S.C.P. Dermoscopic patterns of melanocytic nevi in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kato, H.; Hidano, A. Divided nevus spilus and divided form of spotted grouped pigmented nevus. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1979, 6, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brufau, C.; Moran, M.; Armijo, M. Nevus on nevus. Apropos of 7 case reports, 3 of them associated with other dysplasias, and 1 with an invasive malignant melanoma. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 1986, 113, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.R.; Mihm, M.C., Jr. Origin of cutaneous melanoma in a congenital dysplastic nevus spilus. Arch. Dermatol. 1990, 126, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, N.H.; Malcolm, A.; Long, E.D. Superficial spreading melanoma and blue naevus within naevus spilus–Ultrastructural assessment of giant pigment granules. Dermatology 1997, 194, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeren-Bilgin, I.; Gür, S.; Aydin, O.; Ermete, M. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 1362–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, J.W.; Swindle, L.; Halpern, A.C.; Marghoob, A.A. Agminated acquired melanocytic nevi of the common and dysplastic type. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 52, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsler, V.A.; Krengel, S.; Riviere, J.B.; Waelchli, R.; Chapusot, C.; Al-Olabi, L.; Faivre, L.; Haenssle, H.A.; Weibel, L.; Jeudy, G.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of nevus spilus-type congenital melanocytic nevus: Exquisite genotype-phenotype correlation in mosaic RASopathies. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 2658–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthiah, S.; Polubothu, S.; Husain, A.; Oliphant, T.; Kinsler, V.A.; Rajan, N. A mosaic variant in MAP2K1 is associated with giant naevus spilus-type congenital melanocytic naevus and melanoma development. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, 760–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, A.J.; Ruffolo, A.M.; Miedema, J.; Googe, P.B.; Thomas, N.E. Genetic abnormalities in congenital melanocytic nevi and their associated melanomas. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 45, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Amate, X.; Podlipnik, S.; Riquelme-Mc Loughlin, C.; Carrera, C.; Barreiro-Capurro, A.; García-Herrera, A.; Alós, L.; Malvehy, J.; Puig, S. Clinicopathological, Genetic and Survival Advantages of Naevus-associated Melanomas: A Cohort Study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2021, 101, adv00425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krengel, S.; Hauschild, A.; Schäfer, T. Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: A systematic review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 155, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios-Diaz, R.D.; de Unamuno-Bustos, B.; Abril-Pérez, C.; Pozuelo-Ruiz, M.; Sánchez-Arraez, J.; Torres-Navarro, I.; Botella-Estrada, R. Multiple Primary Melanomas: Retrospective Review in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, K.; Kamada, N.; Mizoguchi, M.; Utani, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Shinkai, H. Malignant melanoma and acquired dermal melanocytosis on congenital nevus spilus. J. Dermatol. 2005, 32, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungureanu, L.; Zboraș, I.; Vasilovici, A.; Vesa, Ș.; Cosgarea, I.; Cosgarea, R.; Șenilă, S. Multiple primary melanomas: Our experience. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Wendt, J.; Rauscher, S.; Sunder-Plassmann, R.; Richtig, E.; Fae, I.; Fischer, G.; Okamoto, I. Risk Factors of Subsequent Primary Melanomas in Austria. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgadottir, H.; Isaksson, K.; Fritz, I.; Ingvar, C.; Lapins, J.; Höiom, V.; Newton-Bishop, J.; Olsson, H. Multiple Primary Melanoma Incidence Trends Over Five Decades: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Tomás, N.; Martínez-Franco, A.; Bañuls, J.; Peñalver, J.C.; Traves, V.; García-Casado, Z.; Requena, C.; Kumar, R.; Nagore, E. Risk factors for the development of a second melanoma in patients with cutaneous melanoma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2295–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingluff, C.L., Jr.; Vollmer, R.T.; Seigler, H.F. Multiple primary melanoma: Incidence and risk factors in 283 patients. Surgery 1993, 113, 330–339. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzinati, S.; Buja, A.; Grotto, G.; Zorzi, M.; Manfredi, M.; Bovo, E.; Del Fiore, P.; Tropea, S.; Dall’Olmo, L.; Rossi, C.R.; et al. Synchronous and metachronous multiple primary cancers in melanoma survivors: A gender perspective. Front. Public. Health 2023, 11, 1195458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostu, A.P.; Ungureanu, L.; Halmagyi, S.R.; Trufin, I.I.; Șenilă, S.C. Multiple primary melanomas: A literature review. Medicine 2023, 102, e34378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Leiter, U. Melanoma epidemiology and trends. Clin. Dermatol. 2009, 27, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganoni, A.M.; Pavoni, L.; Farisoglio, C.; Sereni, E.; Calzavara-Pinton, P. Report of 27 cases of naevus spilus in 2134 patients with melanoma: Is naevus spilus a risk marker of cutaneous melanoma? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 26, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitkopf, C.; Ernst, K.; Hundeiker, M. Neoplasms in nevus spilus. Hautarzt 1996, 47, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Țica, O.; Țica, O. Molecular Diagnostics in Heart Failure: From Biomarkers to Personalized Medicine. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racanelli, J.; Moloney, M.; Siegel, L. Superficial spreading melanoma within a nevus spilus. J. Osteopath. Med. 2023, 123, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, A.J.; Kotsis, S.V.; Chung, K.C. Risk of melanoma arising in large congenital melanocytic nevi: A systematic review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 1968–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenssle, H.A.; Kaune, K.M.; Buhl, T.; Thoms, K.M.; Padeken, M.; Emmert, S.; Schön, M.P. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: Detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009, 61, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoloni Braga, J.C.; Gomes, E.; Macedo, M.P.; Pinto, C.; Duprat, J.; Begnami, M.D.; Rezze, G.G. Early detection of melanoma arising within nevus spilus. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, e31–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Su, Y.; Bing, Z.; Zhao, B. Survival between synchronous and non-synchronous multiple primary cutaneous melanomas-a SEER database analysis. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köteles, M.M.; Țica, O.; Olteanu, G.E. Survey-Based Insights into Romania’s Pathology Services: Charting the Path for Future Progress. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coroi, M.C.; Bakraoui, A.; Sala, C.; Ţica, O.; Ţica, O.A.; Jurcă, M.C.; Jurcă, A.D.; Holhoş, L.B.; Bălăşoiu, A.T.; Todor, L. Choroidal melanoma, unfavorable prognostic factors. Case report and review of literature. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2019, 60, 673–678. [Google Scholar]

| Year (Age) | Site | Relation to SLN | Clinical Features | Histological Type | Breslow (mm) | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 (66) | Left shoulder | Within SLN | Verrucous black plaque, 10 × 8 mm, eccentric pigmentation | Superficial spreading melanoma, in situ | – | pTis |

| 2022 (75) | Left arm | Within SLN | Flat brown macule, 6 × 7 mm, atypical reticular network on dermoscopy | Superficial spreading melanoma, in situ | – | pTis |

| 2022 (75) | Posterior parietal scalp | Outside SLN | Irregular brown-black plaque, 14 × 10 mm | Superficial spreading melanoma, invasive (Clark II) | 0.3 | pT1a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frațilă, S.; Țica, O.; Rațiu, I.A.; Ardelean, A. Multiple Melanomas on Speckled Lentiginous Nevus: A Systematic Review and a Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186366

Frațilă S, Țica O, Rațiu IA, Ardelean A. Multiple Melanomas on Speckled Lentiginous Nevus: A Systematic Review and a Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186366

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrațilă, Simona, Ovidiu Țica, Ioana Adela Rațiu, and Alexandra Ardelean. 2025. "Multiple Melanomas on Speckled Lentiginous Nevus: A Systematic Review and a Case Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186366

APA StyleFrațilă, S., Țica, O., Rațiu, I. A., & Ardelean, A. (2025). Multiple Melanomas on Speckled Lentiginous Nevus: A Systematic Review and a Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186366