Psychosocial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Adults Receiving Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim and Research Questions

- (a)

- Which aspects of the psychosocial well-being of informal caregivers of adults receiving HMV are most frequently explored in the literature?

- (b)

- What research methods and instruments are employed to investigate the psychosocial well-being of these caregivers?

- (c)

- What knowledge gaps can be identified based on the literature?

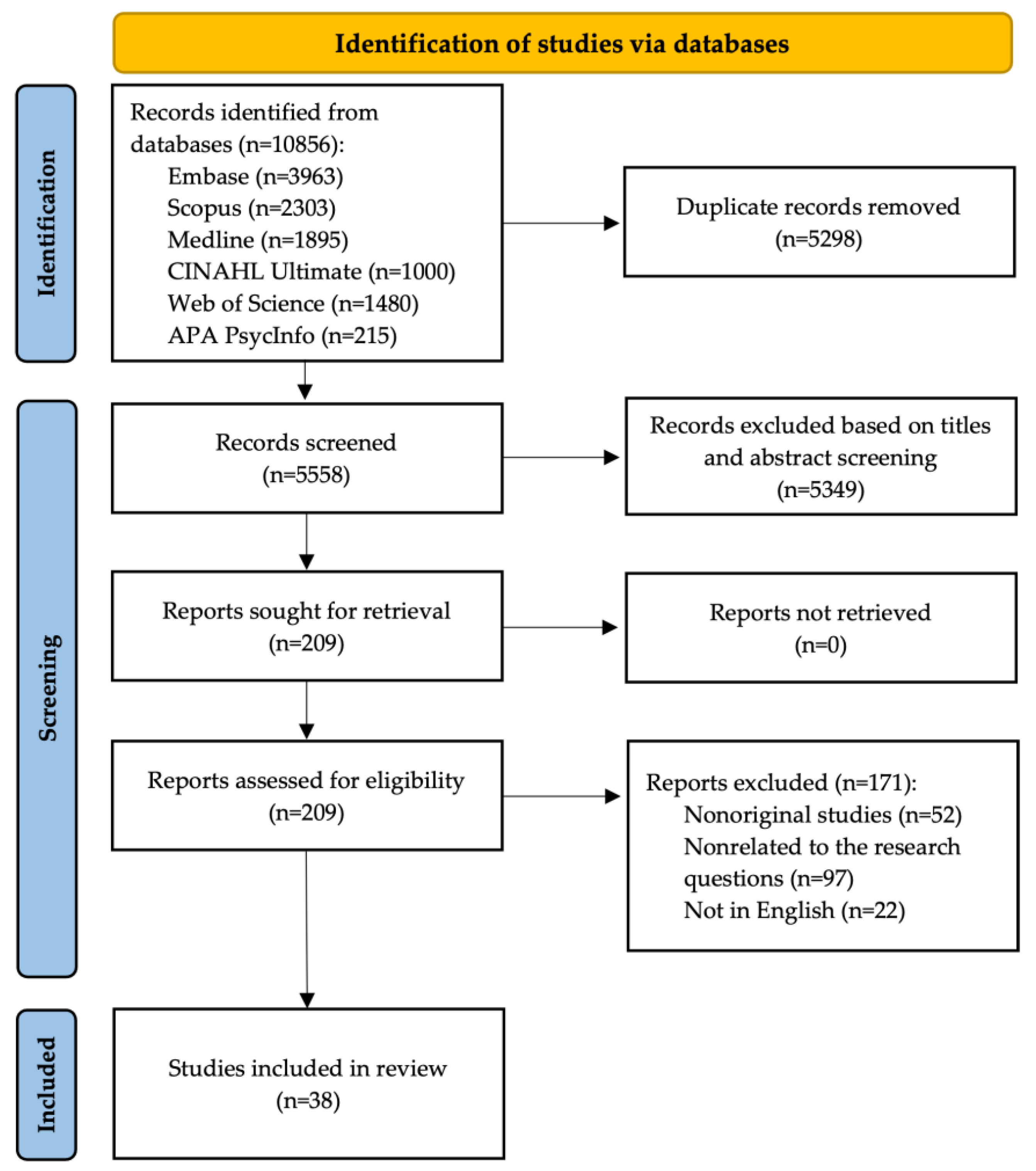

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

- (1)

- Primary, peer-reviewed, and original full-length research articles published in a scientific journal;

- (2)

- Studies that report evidence on the psychosocial well-being of informal, unpaid caregivers for adults receiving HMV;

- (3)

- Studies that employed quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research methods;

- (4)

- Full-text available online.

- (1)

- Secondary research (e.g., systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and narrative reviews), nonoriginal publications (e.g., editorials, commentaries, and letters to the editor), gray literature (e.g., dissertations, theses, study protocols, conference abstracts, and book chapters), or single case studies;

- (2)

- Studies involving heterogeneous populations, in which data specific to informal caregivers of adults receiving HMV were not separately reported or extractable;

- (3)

- Studies on caregivers of individuals using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or home oxygen therapy only;

- (4)

- Published in a language other than English.

2.3. Charting Process and Reporting of Results

- (1)

- Publication details;

- (2)

- Methods;

- (3)

- Characteristics of the study population;

- (4)

- Key concepts and findings.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Sociodemographic Findings

3.3. Caregiver Burden

3.4. Mental Health and Quality of Life

| Publication | Caregivers of Individuals Receiving HMV | VAIs Living at Home | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Year | n | Age (y) | Female (%) | Relationship to Patient (%) | Age (y) | Male (%) | Type of Ventilation (%) | Duration of HMV |

| Quantitative studies: | |||||||||

| Thomas et al. [37] | 1992 | 44 | 47.3 ± 13.5 | 61% | 27% mothers, 18% husbands, 14% wives, 14% fathers, 14% daughters, 5% sisters, and 9% others | 43 ± 22.8 | 59% | n/a | 20.5 (IQR n/a) mo |

| Ferrario et al. [18] | 2001 | 40 | 56.50 ± 14.30 | 63% | 55% spouses and 45% others | 65 ± 9.1 | 73% | n/a | 24.3 ± 20.1 mo |

| Kaub-Wittemer et al. [27] | 2003 | 52 | n/a | 81% | 98% spouses and 2% daughters | 60.0 ± n/a (NIV); 61.6 ± n/a (IV) | 79% | 60% NIV; 40% IV | 13.8 ± n/a mo (NIV); 34.6 ± n/a mo (IV) |

| Tsara et al. [28] | 2006 | 50 | 47.98 ± 14.2 | majority were female | 42% spouses, 39% children, and 19% others | 61 (IQR n/a) | predominantly male | 88% NIV; 12% IV | 3.5 ± 2.4 y |

| Kim & Kim [20] | 2014 | 83 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 59.66 ± 10.97 | 63% | 77% IV; 23% NIV | 25.56 ± 19.91 |

| Liu et al. [38] | 2017 | 80 | 50.59 ± 14.92 | 73% | 45% children, 33% spouses, 17% sons/daughters, and 5% others | 63.75 ± 16.95 | 61% | 100% IV | 32.04 ± 33.43 mo |

| Jacobs et al. [39] | 2021 | 34 | 59.5 ± 15.9 | 65% | 38% parents, 29% partners, 24% children, and 9% siblings | 53.8 ± 21.3 | 56% | 100% IV | 51.2 (IQR 28–199) mo |

| Liang et al. [40] | 2022 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 61.94 ± 19.50 | 53% | n/a | n/a |

| Pandian et al. [11] | 2022 | 34 | 43.3 ± 15.9 | n/a | n/a | 51.3 ± 12.2 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Volpato et al. [33] | 2022 | 66 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 69.1 ± 8.6 | 45% | 100% NIV | n/a |

| Esmaeili et al. [17] | 2023 | 51 | 46.60 ± 12.24 (Inter.); 43.56 ± 9.83 (Ctrl.) | n/a | n/a | 54.85 ± 15.24 (Inter.); 52.78 ± 13.89 (Ctrl.) | 50% (Inter.); 48% (Ctrl.) | 100% IV | n/a |

| Karagün et al. [19] | 2023 | 250 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 34% NIV | n/a |

| Marcus et al. [41] | 2023 | 34 | 59.5 ± 15.9 | 65% | 38% parents, 29% partners, 24% children, and 9% siblings | 53.8 ± 21.3 | n/a | 100% IV | 51.2 (IQR 28–199) mo |

| Tülek et al. [13] | 2023 | 66 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 53% IV; 10% NIV | n/a |

| Kavand & Asgari [14] | 2024 | 51 | 46.60 ± 12.24 (Inter.); 43.56 ± 98.30 (Ctrl.) | 78% | 45% spouses, 35% children, and 20% parents | 54.85 ± 15.24 (Inter.); 52.78 ± 13.89 (Ctrl.) | 51% | 100% IV | n/a |

| Lee et al. [34] | 2024 | 59 | 62 (IQR 55–70) | 80% | 56% spouses, 39% children, and 5% other family members | 62 (IQR 55–70) | 59% | 95% IV | n/a |

| Płaszewska et al. [7] | 2024 | 58 | 53.81 ± 13.73 | 66% | n/a | 56.47 ± 14.62 | 52% | 64% IV; 36% NIV | 3.54 ± 2.63 y |

| Qualitative studies: | |||||||||

| Findeis et al. [21] | 1994 | 13 | 50.92 ± 14.15 | n/a | 31% wives, 23% husbands, 15% mothers, 15% parents, 8% fathers, and 8% girlfriends | 42 ± 18.24 | 58% | n/a | n/a |

| van Kesteren et al. [1] | 2001 | 43 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 36.74 ± 15.88 | 63% | 68% IV; 32% NIV | 83.89 ± 40.57 mo |

| Akiyama et al. [35] | 2006 | 12 | 56.1 ± 13.2 | 83% | 75% spouses, 17% mothers, and 8% daughters | n/a | n/a | 83% IV; 17% NIV | n/a |

| Sundling et al. [42] | 2009 | 8 | range 40–74 | 75% | 100% spouses | range 45–75 | 71% | 100% NIV | range 3–15 mo |

| Huang & Peng [29] | 2010 | 15 | 57.7 ± n/a | 60% | 33% children, 27% spouses, 27% mothers, and 13% daughters-in-law | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Dale et al. [5] | 2018 | 14 | n/a | 100% | 74% spouses | 54.89 ± 18.21 | 53% IV; 47% NIV | n/a | |

| Dickson et al. [43] | 2018 | 8 | 51.13 ± 8.68 | 88% | 38% spouses, 38% siblings, and 24% mothers | 44.25 ± 15.94 | 88% | n/a | range 4–20 y |

| Schaepe & Ewers [16] | 2018 | 15 | 62 ± 11.75 | 80% | 60% spouses, 20% mothers, 13% children, and 7% sisters | n/a | n/a | 87% IV; 13% NIV | 11.15 ± 13.46 |

| MacLaren et al. [36] | 2019 | 6 | n/a | n/a | 83% partners and 17% parents | 44 (IQR n/a) | 93% | 79% NIV; 21% IV | 21% <1 y, 43% 1–9 y, and 36% >10 y |

| Yamaguchi et al. [30] | 2019 | 14 | 53.86 ± 4.31 | 86% | 86% mothers and 14% fathers | 23.20 ± 4.97 | 100% | 60% NIV; 40% IV | n/a |

| Esmaeili et al. [22] | 2022 | 9 | 39.5 ± 6.64 | n/a | 67% children, 22% spouses, and 11% parents | n/a | n/a | 100% IV | n/a |

| Khankeh et al. [31] | 2022 | 12 | n/a | n/a | 25% parents, 25% children, 17% siblings, 17% spouses, and 16% others | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Aydin et al. [23] | 2024 | 21 | 38.7 ± 10.3 | 81% | 52% mothers, 24% daughters, 9% fathers, 5% grandmothers, 5% siblings, and 5% sons | n/a | 48% | 100% IV | n/a |

| Mixed-method studies: | |||||||||

| Smith et al. [44] | 1991 | 20 | 51.25 ± 14.41 | n/a | 35% wives, 20% husbands, 20% mothers, 5% fathers, 5% sons, 5% daughters, 5% brothers, and 5% VAIs described themselves as a caregiver | 49.10 ± 17.76 | 75% | 50% IV; 50% NIV | 42.80 ± 67.38 mo |

| Moss et al. [45] | 1993 | 19 | n/a | 90% | n/a | 57 ± n/a range 36–78 | 79% | 84% IV; 16% NIV | 20 ± n/a mo range 3–70 mo |

| Smith et al. [32] | 1994 | 20 | 20–74 | 65% | 50% spouses, 25% parents, 15% children, 5% close relatives, and 5% described themselves as a caregiver | 18–74 | n/a | 55% IV; 45% NIV | 45% ≤1 y, 35% 2–4 y, 15% 5–9 y, and 5% 26 y |

| Marchese et al. [25] | 2008 | 77 | n/a | 81% | 71% spouses, 23% parents, 4% sons, and 2% close friend | 58.2 ± 17.5 | 70% | 100% IV | n/a |

| Evans et al. [24] | 2012 | 21 | 53.86 ± 14.30 | 62% | 24% mothers, 24% fathers, 24% wives, 9% daughters, 9% sons, 5% husbands, and 5% sisters | 45 ± 13 | n/a | 100% IV | 8 ± 5 |

| Baxter et al. [26] | 2013 | 16 | n/a | n/a | 69% wives, 19% husbands, 6% daughters, and 6% other family members | n/a | n/a | 100% NIV | n/a |

| Klingshirn et al. [15] | 2022 | 5 | 52.8 ± 5.36 | 80% | 60% parents and 40% spouses | 46.86 ± 15.40 | 64% | 71% IV; 29% NIV | 11.67 ± 8.0 |

| Sheers et al. [46] | 2024 | 12 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 78% (Inter.); 82% (Ctrl.) | 100% NIV | n/a |

| Authors | Year | Country | Study Period | Instruments Used to Assess Caregivers | Key Concepts Related to Caregivers of VAIs Living at Home |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies: | |||||

| Thomas et al. [37] | 1992 | United States | 1989 | Caregiver Needs | Caregiver needs |

| Ferrario et al. [18] | 2001 | Italy | n/a | Family Strain Questionnaire | Family strain |

| Kaub-Wittemer et al. [27] | 2003 | Germany | n/a | Author-developed questionnaire; Profile of Mood States; Munich Quality of Life Dimensions List | Quality of life; depression; fatigue; vigor; anger; patient care; home and personal situation; partnership; burden |

| Tsara et al. [28] | 2006 | Greece | n/a | Family Burden Questionnaire | Burden; coping |

| Kim & Kim [20] | 2014 | South Korea | August 2008–April 2009 | Zarit Burden Interview; 36-Item Short Form Health Survey | Burden; quality of Life |

| Liu et al. [38] | 2017 | Taiwan | June–December 2010 | Burden Assessment Scale | Burden |

| Jacobs et al. [39] | 2021 | Israel | May 2016–April 2018 | Caregiver Strain Index | Strain; cost of care |

| Liang et al. [40] | 2022 | Taiwan | November 2016–June 2017 | Family Caregiver Belief Scale | Beliefs |

| Pandian et al. [11] | 2022 | Cross-country | n/a | Author-developed questionnaire | Anxiety; fatigue; mood; loneliness |

| Volpato et al. [33] | 2022 | Italy | May 2015–December 2017 | Caregiver Burden Inventory; Caregiver Burden Scale; Zarit Burden Interview | Home adaptation vs. outpatient adaptation; burden; satisfaction |

| Esmaeili et al. [17] | 2023 | Iran | June 2020–January 2022 | Zarit Burden Interview | Effect of training; burden |

| Karagün et al. [19] | 2023 | Turkey | September 2019–April 2020 | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale—Short Form; Zarit Burden Interview | Anxiety; depression; quality of life; burden |

| Marcus et al. [41] | 2023 | Israel | May 2016–April 2018 | Caregiver Strain Index | Strain |

| Tülek et al. [13] | 2023 | Turkey | September 2015–March 2016 | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; EQ-5D; Zarit Burden Interview; Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support | Burden; quality of life; anxiety; depression; social support |

| Kavand & Asgari [14] | 2024 | Iran | July 2020–November 2021 | Functional skills checklist; Zarit Burden Interview | Effect of training; burden |

| Lee et al. [34] | 2024 | South Korea | August–October 2022 | Patient Health Questionnaire; Preparedness for Caregiving Scale; Caregiver Competence Scale | Depression; emotional difficulties; care preparedness; care capability |

| Płaszewska et al. [7] | 2024 | Poland | n/a | Caregiver Burden Scale; Social Support Scale; Brief COPE | Burden; social support; coping |

| Qualitative studies: | |||||

| Findeis et al. [21] | 1994 | United States | n/a | Semi-structured interviews; List of caregiving tasks; Caregiving Appraisal Scale | Caregiving tasks; burden; impact of caregiving; mastery of the caregiving role; satisfaction |

| van Kesteren et al. [1] | 2001 | Netherlands | January 1996–May 1998 | Semi-structured interviews | Strain; receiving information; unexpected problems; obstacles; expected help; change in life; choosing respiratory support again |

| Akiyama et al. [35] | 2006 | Japan | August 2001–September 2002 | Semi-structured interviews | Hesitation and regret; support |

| Sundling et al. [42] | 2009 | Sweden | 2002–2005 | In-depth interviews | Getting to know the ventilator; embracing the ventilator; being on the ventilator on a 20–24 h basis |

| Huang & Peng [29] | 2010 | Taiwan | January–December 2007 | In-depth interviews | Adaptation |

| Dale et al. [5] | 2018 | Canada | n/a | Semi-structured interviews | Facilitators and barriers |

| Dickson et al. [43] | 2018 | United Kingdom | n/a | Semi-structured interviews | Negotiating boundaries of care and finding a “fit” |

| Schaepe & Ewers [16] | 2018 | Germany | June 2014–June 2015 | Semi-structure interviews; Burden Scale for Family Caregivers | Burden; contribution of family caregivers to safety in HMV |

| MacLaren et al. [36] | 2019 | United Kingdom | 2015–2016 | Semi-structured interviews | Care; personal impact of caring. |

| Yamaguchi et al. [30] | 2019 | Japan | March 2013–September 2016 | Serial interviews | Family relationships |

| Esmaeili et al. [22] | 2022 | Iran | November 2019–May 2020 | Semi-structured interviews | Educational, psychological, and economical needs |

| Khankeh et al. [31] | 2022 | Iran | 2015, 2019 | Semi-structured interviews | Challenging care with stress and ambivalence; step-by-step care delegation |

| Aydin et al. [23] | 2024 | Turkey | April 2019–June 2019 | Semi-structured interviews | Physiology; self-concept; role–function; interdependence |

| Mixed-method studies: | |||||

| Smith et al. [44] | 1991 | United States | n/a | Semi-structured interviews; Family Coping Scale; Family Apgar | Adaptation; coping; perceptions of family function |

| Moss et al. [45] | 1993 | United States | n/a | Structured interviews | Decision on HMV; benefits and burdens; costs of HMV; attitudes toward HMV |

| Smith et al. [32] | 1994 | United States | n/a | Semi-structured interviews; Learning Needs Checklist; Caregiver Reaction Inventory; Family Coping Strategies Scales; Family Apgar | Responsibilities; learning needs; reactions to caring and caregiving; coping; perceptions of family function |

| Marchese et al. [25] | 2008 | Italy | January 1995–December 2004 | Structured interviews; Caregiver Strain Index | Benefits and burdens; attitudes |

| Evans et al. [24] | 2012 | Canada | n/a | Semi-structured interviews; Caregiver Burden Inventory | Sense of duty; restriction on day-to-day life; burden; training and education; paid support |

| Baxter et al. [26] | 2013 | United Kingdom | n/a | Semi-structured interviews; 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; Caregiver Strain Index | Quality of life; strain; impact of NIV; burden; role change; difficulty having time away; professional support |

| Klingshirn et al. [15] | 2022 | Germany | June 2019–August 2020 | Semi-structured interviews; Burden Scale for Family Caregivers | Burden; daily care; social relationships and participation; safety; care coordination; improvement |

| Sheers et al. [46] | 2024 | Australia | August 2020–August 2021 | Semi-structured interviews; Zarit Burden Interview | In-home model of NIV initiation vs. single-day admission; advantages and disadvantages of care; burden and barriers; benefits and enablers |

3.5. Coping and Spirituality

3.6. Caregivers’ Needs and Support Expectations

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Research Gaps and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ctrl. | Control group |

| HMV | Home mechanical ventilation |

| Inter. | Intervention group |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| IV | Invasive ventilation |

| mo | Months |

| n | Sample size |

| n/a | Not applicable |

| NIV | Non-invasive ventilation |

| VAIs | Ventilator-assisted individuals |

| y | Years |

References

- Van Kesteren, R.G.; Velthuis, B.; Van Leyden, L.W. Psychosocial Problems Arising from Home Ventilation. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 80, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Suh, E.-S. Home Mechanical Ventilation: Back to Basics. Acute Crit. Care 2020, 35, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourke, S.C.; Tomlinson, M.; Williams, T.L.; Bullock, R.E.; Shaw, P.J.; Gibson, G.J. Effects of Non-Invasive Ventilation on Survival and Quality of Life in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annane, D.; Orlikowski, D.; Chevret, S. Nocturnal Mechanical Ventilation for Chronic Hypoventilation in Patients with Neuromuscular and Chest Wall Disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD001941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, C.M.; King, J.; Nonoyama, M.; Carbone, S.; McKim, D.; Road, J.; Rose, L. Transitions to Home Mechanical Ventilation: The Experiences of Canadian Ventilator-Assisted Adults and Their Family Caregivers. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatosz-Muc, M.; Kopacz, B.; Fijałkowska-Nestorowicz, A. Quality of Life and Stress Levels in Patients under Home Mechanical Ventilation: What Can We Do to Improve Functioning Patients at Home? A Survey Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płaszewska-Żywko, L.; Fajfer-Gryz, I.; Cichoń, J.; Kózka, M. Burden, Social Support, and Coping Strategies in Family Caregivers of Individuals Receiving Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povitz, M.; Rose, L.; Shariff, S.Z.; Leonard, S.; Welk, B.; Jenkyn, K.B.; Leasa, D.J.; Gershon, A.S. Home Mechanical Ventilation: A 12-Year Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Respir. Care 2018, 63, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, V.; Hopkins, B.S.; Yang, C.J.; Ward, E.; Sperry, E.D.; Khalil, O.; Gregson, P.; Bonakdar, L.; Messer, J.; Messer, S.; et al. Amplifying Patient Voices amid Pandemic: Perspectives on Tracheostomy Care, Communication, and Connection. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tülek, Z.; Özakgül, A.; Alankaya, N.; Dik, A.; Kaya, A.; Ünalan, P.C.; Özaydin, A.N.; İdrisoğlu, H.A. Care Burden and Related Factors among Informal Caregivers of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2023, 24, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavand, B.; Asgari, P. An Investigation of the Effect of the Universal Model of Family-Centered Care on Patient and Family Outcomes in Patients under Home Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Fam. Pract. 2024, 41, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingshirn, H.; Gerken, L.; Hofmann, K.; Heuschmann, P.U.; Haas, K.; Schutzmeier, M.; Brandstetter, L.; Wurmb, T.; Kippnich, M.; Reuschenbach, B. Comparing the Quality of Care for Long-Term Ventilated Individuals at Home versus in Shared Living Communities: A Convergent Parallel Mixed-Methods Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaepe, C.; Ewers, M. “I See Myself as Part of the Team”—Family Caregivers’ Contribution to Safety in Advanced Home Care. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.; Bahramnezhad, F.; Fattah Ghazi, S.; Asgari, P. Effectiveness of a Supportive Program on Caregiver Burden of Families Caring for Patients on Invasive Mechanical Ventilation at Home: An Experimental Study. Creat. Nurs. 2023, 29, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, S.R.; Zotti, A.M.; Zaccaria, S.; Donner, C.F. Caregiver Strain Associated with Tracheostomy in Chronic Respiratory Failure. Chest 2001, 119, 1498–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagün, Z.; Çelik, D.; Aydin, M.S.; Gündoǧmuş, I.; Şipit, Y.T. Hidden Face of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Effects of Patients’ Psychiatric Symptoms on Caregivers’ Burden and Quality of Life. Eur. Res. J. 2023, 9, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-H.; Kim, M.S. Ventilator Use, Respiratory Problems, and Caregiver Well-Being in Korean Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Receiving Home-Based Care. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2014, 46, e25–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findeis, A.; Larson, J.L.; Gallo, A.; Shekleton, M. Caring for Individuals Using Home Ventilators: An Appraisal by Family Caregivers. Rehabil. Nurs. 1994, 19, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Asgari, P.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.; Bahramnezhad, F.; Fattah Ghazi, S. A Contextual Needs Assessment of Families with Home Invasive Mechanical Ventilation Patients: A Qualitative Study. Chronic Illn. 2022, 18, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Bulut, T.Y.; Avcİ, İ.A. Adaptation of Caregivers of Individuals on Mechanical Ventilation to Caregiving Role. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 28, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.; Catapano, M.A.; Brooks, D.; Goldstein, R.S.; Avendano, M. Family Caregiver Perspectives on Caring for Ventilator-Assisted Individuals at Home. Can. Respir. J. 2012, 19, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchese, S.; Lo Coco, D.; Lo Coco, A. Outcome and Attitudes toward Home Tracheostomy Ventilation of Consecutive Patients: A 10-Year Experience. Respir. Med. 2008, 102, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, S.K.; Baird, W.O.; Thompson, S.; Bianchi, S.M.; Walters, S.J.; Lee, E.; Ahmedzai, S.H.; Proctor, A.; Shaw, P.J.; McDermott, C.J. The Impact on the Family Carer of Motor Neurone Disease and Intervention with Noninvasive Ventilation. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaub-Wittemer, D.; Steinbüchel, N.v.; Wasner, M.; Laier-Groeneveld, G.; Borasio, G.D. Quality of Life and Psychosocial Issues in Ventilated Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Their Caregivers. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2003, 26, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsara, V.; Serasli, E.; Voutsas, V.; Lazarides, V.; Christaki, P. Burden and Coping Strategies in Families of Patients under Noninvasive Home Mechanical Ventilation. Respiration 2006, 73, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-T.; Peng, J.-M. Role Adaptation of Family Caregivers for Ventilator-Dependent Patients: Transition from Respiratory Care Ward to Home. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 1686–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Sonoda, E.; Suzuki, M. The Experience of Parents of Adult Sons with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Regarding Their Prolonged Roles as Primary Caregivers: A Serial Qualitative Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khankeh, H.R.; Ebadi, A.; Norouzi Tabrizi, K.; Moradian, S.T. Home Health Care for Mechanical Ventilation-Dependent Patients: A Grounded Theory Study. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e2157–e2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.E.; Mayer, L.S.; Perkins, S.B.; Gerald, K.; Pingleton, S.K. Caregiver Learning Needs and Reactions to Managing Home Mechanical Ventilation. Heart Lung 1994, 23, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Volpato, E.; Vitacca, M.; Ptacinsky, L.; Lax, A.; D’Ascenzo, S.; Bertella, E.; Paneroni, M.; Grilli, S.; Banfi, P. Home-Based Adaptation to Night-Time Non-Invasive Ventilation in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, S.H.; Cho, B.; Kim, K.H.; Jang, M.S.; Shin, J.; Hwang, I.; Choi, S.-J.; Sung, J.-J.; Kim, M.S. Burden and Preparedness of Care Partners of People Living with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis at Home in Korea: A Care Partner Survey. Muscle Nerve 2024, 70, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, M.O.; Kayama, M.; Takamura, S.; Kawano, Y.; Ohbu, S.; Fukuhara, S. A Study of the Burden of Caring for Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (MND) in Japan. Br. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2006, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, J.; Smith, P.; Rodgers, S.; Bateman, A.P.; Ramsay, P. A Qualitative Study of Experiences of Health and Social Care in Home Mechanical Ventilation. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.M.; Ellison, K.; Howell, E.V.; Winters, K. Caring for the Person Receiving Ventilatory Support at Home: Care Givers’ Needs and Involvement. Heart Lung 1992, 21, 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-F.; Lu, M.-C.; Fang, T.-P.; Yu, H.-R.; Lin, H.-L.; Fang, D.-L. Burden on Caregivers of Ventilator-Dependent Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine 2017, 96, e7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.M.; Marcus, E.-L.; Stessman, J. Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: A Comparison of Patients Treated at Home Compared With Hospital Long-Term Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.-Y.; Lee, M.-D.; Lin, K.-C.; Lin, L.-H.; Yu, S. Determinants of the Health Care Service Choices of Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation Patients: Applying Andersen’s Behavioral Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, E.-L.; Jacobs, J.M.; Stessman, J. Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation and Caregiver Strain: Home vs. Long-Term Care Facility. Palliat. Support Care 2023, 21, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundling, I.-M.; Ekman, S.-L.; Weinberg, J.; Klefbeck, B. Patients’ with ALS and Caregivers’ Experiences of Non-Invasive Home Ventilation. Adv. Physiother. 2009, 11, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.; Karatzias, T.; Gullone, A.; Grandison, G.; Allan, D.; Park, J.; Flowers, P. Negotiating Boundaries of Care: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of the Relational Conflicts Surrounding Home Mechanical Ventilation Following Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2018, 6, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.E.; Mayer, L.S.; Parkhurst, C.; Perkins, S.B.; Pingleton, S.K. Adaptation in Families with a Member Requiring Mechanical Ventilation at Home. Heart Lung 1991, 20, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moss, A.H.; Casey, P.; Stocking, C.B.; Roos, R.P.; Brooks, B.R.; Siegler, M. Home Ventilation for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients: Outcomes, Costs, and Patient, Family, and Physician Attitudes. Neurology 1993, 43, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheers, N.L.; Hannan, L.M.; Rautela, L.; Graco, M.; Jones, J.; Retica, S.; Saravanan, K.; Burgess, N.; McGaw, R.; Donovan, A.; et al. NIV@Home: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of in-Home Noninvasive Ventilation Initiation Compared to a Single-Day Admission Model. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2024, 26, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Gender Differences in Caregiving among Family—Caregivers of People with Mental Illnesses. World J. Psychiatr. 2016, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella Carbó, G.F.; García-Orellán, R. Burden and Gender Inequalities around Informal Care. Invest. Educ. Enferm. 2020, 38, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Heffernan, C.; Tan, J. Caregiver Burden: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Yu, S. Exploring Factors Influencing Caregiver Burden: A Systematic Review of Family Caregivers of Older Adults with Chronic Illness in Local Communities. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciarelli, G.; Ausili, D.; Galbussera, A.A.; Rebora, P.; Savini, S.; Simeone, S.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Quality of Life, Anxiety, Depression and Burden among Stroke Caregivers: A Longitudinal, Observational Multicentre Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandepitte, S.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Putman, K.; Verhaeghe, S.; Verdonck, C.; Annemans, L. Effectiveness of Respite Care in Supporting Informal Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Priego-Cubero, E.; López-Martínez, C.; Orgeta, V. Subjective Caregiver Burden and Anxiety in Informal Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Informal Caregiving, Loneliness and Social Isolation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hu, J.; Bai, X. A Systematic Review of Literature on Caregiving Preparation of Adult Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T.; Raimundo, M.; De Sousa, S.B.; Barata, M.; Cabrita, T. Relationship between Burden, Quality of Life and Difficulties of Informal Primary Caregivers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of the Contributions of Public Policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Francis, L.E. Quality of Relationships and Caregiver Burden: A Longitudinal Study of Caregivers for Advanced Cancer Patients. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2024, 79, gbad165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cichoń, J.; Homa, M.; Płaszewska-Żywko, L.; Kózka, M. Psychosocial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Adults Receiving Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176294

Cichoń J, Homa M, Płaszewska-Żywko L, Kózka M. Psychosocial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Adults Receiving Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176294

Chicago/Turabian StyleCichoń, Jakub, Monika Homa, Lucyna Płaszewska-Żywko, and Maria Kózka. 2025. "Psychosocial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Adults Receiving Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Scoping Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176294

APA StyleCichoń, J., Homa, M., Płaszewska-Żywko, L., & Kózka, M. (2025). Psychosocial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Adults Receiving Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176294