Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the German Version of OBI-Care in Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

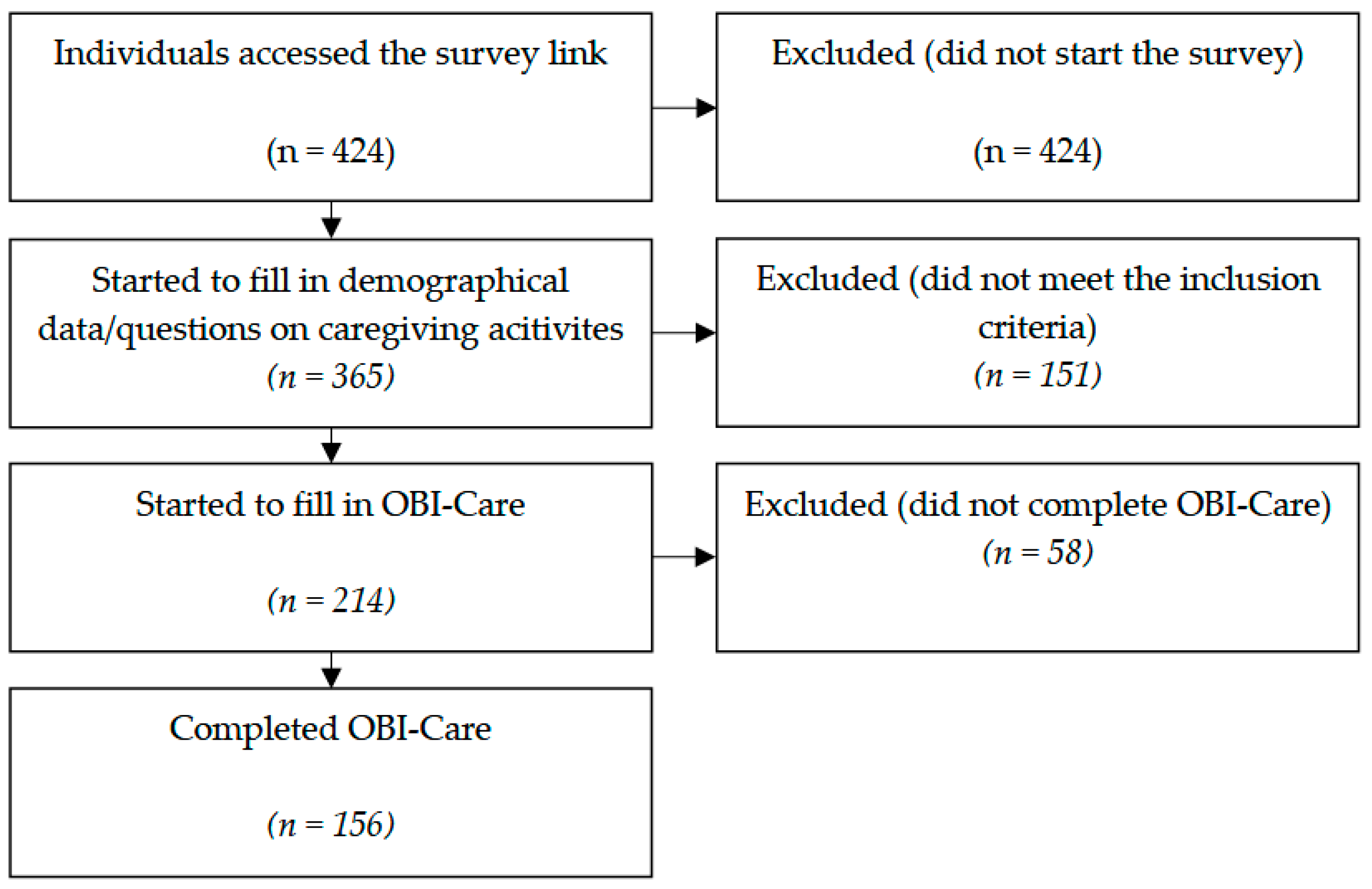

3.1. Participants

3.2. Construct Validity

3.3. Internal Consistency

3.4. Floor and Ceiling Effects

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A-OBS | Adolescent Occupational Balance Scale |

| CROB | Collaborative Research on Occupational Balance |

| DIF | Differential Item Functioning |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| OBI-Care | Occupational Balance in Informal Caregivers |

| OBQ | Occupational Balance Questionnaire |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PROM | Patient Reported Outcome Measure |

| PSI | Person Separation Index |

| RSM | Rating Scale Model |

| SDO-OB | Satisfaction with Daily Occupations and Occupational Balance questionnaire |

References

- Gunduz, M.E.; Bucak, B.; Keser, Z. Advances in Stroke Neurorehabilitation. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryś, B.; Bąk, E. Factors Determining the Burden of a Caregiver Providing Care to a Post-Stroke Patient. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, J.; Park, M.H. Family’s Caregiving Status and Post-Stroke Functional Recovery During Subacute Period from Discharge to Home: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, M.; Poulsen, P.B.; Reiche, T.; Nissen, N.P.; Gundgaard, J. Costs of Informal Care for People Suffering from Dementia: Evidence from a Danish Survey. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2011, 1, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwar, L.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Psychosocial consequences of transitioning into informal caregiving in male and female caregivers: Findings from a population-based panel study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 264, 113281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorawara-Bhat, R.; Graupner, J.; Molony, J.; Thompson, K. Informal Caregiving in a Medically Underserved Community: Challenges, Construction of Meaning, and the Caregiver-Recipient Dyad. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819844670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pysklywec, A.; Plante, M.; Auger, C.; Mortenson, W.B.; Eales, J.; Routhier, F.; Demers, L. The positive effects of caring for family carers of older adults: A scoping review. Int. J. Care Caring 2020, 4, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Family Caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckel, J.; Bom, J. Revisiting longer-term health effects of informal caregiving: Evidence from the UK. J. Econ. Ageing 2022, 21, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, C.; Alexander, H.; Hagen, S. Stroke Patients’ Informal Caregivers. Stroke 1999, 30, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Tang, Y.; Zeng, P.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z. Psychological status on informal carers for stroke survivors at various phases: A cohort study in China. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1173062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, A. A theory of the human need for occupation. J. Occup. Sci. 1993, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrand, I.; Larsson, I.; Larsson, M.; Ekman, A.; Heden, L.; Laakso, K.; Lindmark, U.; Nunstedt, H.; Oxelmark, L.; Pennbrant, S.; et al. Health-promoting factors among students in higher education within health care and social work: A cross-sectional analysis of baseline data in a multicentre longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Håkansson, C.; Leo, U.; Oudin, A.; Arvidsson, I.; Nilsson, K.; Österberg, K.; Persson, R. Organizational and social work environment factors, occupational balance and no or negligible stress symptoms among Swedish principals–a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dür, M.; Steiner, G.; Fialka-Moser, V.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Stoffer, M.; Prodinger, B.; Dejaco, C.; Smolen, J.; Stamm, T. Associations between Occupational Balance and Immunology: Differences in Health Conditions, Employment Status Und Gender. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dür, M.; Unger, J.; Stoffer, M.; Dragoi, R.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Veronika, F.-M.; Josef, S.; Stamm, T. Definitions of occupational balance and their coverage by instruments. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 78, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagman, P.; Håkansson, C.; Björklund, A. Occupational balance as used in occupational therapy: A concept analysis. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 19, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahpour, M.; Tham, K.; Joghataei, M.T.; Eriksson, G.; Jonsson, H. Occupational Gaps in Everyday Life after Stroke and the Relation to Functioning and Perceived Life Satisfaction. OTJR 2011, 31, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, S. Implementing Sensitivity and Contingency in Medical Contexts: The Case of Prematurity. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, H.; Persson, D. Towards an Experiential Model of Occupational Balance: An Alternative Perspective on Flow Theory Analysis. J. Occup. Sci. 2006, 13, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Miller, W.; Reid, H.; Petry Moecke, D.M.; Crosbie, S.; Kamurasi, I.; Girt, M.; Peter, M.; Petlitsyna, P.; Friesen, M.; et al. How is resilience conceptualized and operationalized in occupational therapy and occupational science literature? Protocol for a scoping review. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocup. 2022, 30, e3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, B.; Muriithi, J. Occupational Resilience: A New Concept in Occupational Science. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74 (Suppl. S1), 7411505137p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013, 346, f167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagman, P.; Håkansson, C. Introducing the Occupational Balance Questionnaire (OBQ). Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 21, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, M.; Argentzell, E. Perception of occupational balance by people with mental illness: A new methodology. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 23, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guney Yılmaz, G.; Avci, H.; Aki, E. A new tool to measure occupational balance: Adolescent Occupational Balance Scale (A-OBS). Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 30, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dür, M.; Röschel, A.; Oberleitner-Leeb, C.; Herrmanns, V.; Pichler-Stachl, E.; Mattner, B.; Pernter, S.-D.; Wald, M.; Urlesberger, B.; Kurz, H.; et al. Development and validation of a self-reported questionnaire to assess occupational balance in parents of preterm infants. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röschel, A.; Wagner, C.; Dur, M. Examination of validity, reliability, and interpretability of a self-reported questionnaire on Occupational Balance in Informal Caregivers (OBI-Care)—A Rasch analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.M.Y. Validation study can be a separate study design. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 2016, 5, 2421–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.; Yan, Z.; Heene, M. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA Relevance). 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj/eng (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Linacre, J. Sample Size and Item Calibration Stability. 7th Edition. 1994, p. 328. Available online: https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt74m.htm (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Dodge, Y. Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. In The Concise Encyclopedia of Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Hadzibajramovic, E.; Schaufeli, W.; De Witte, H. A Rasch analysis of the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.J.; Chen, C.T.; Lin, G.H.; Wu, T.Y.; Chen, S.S.; Lin, L.F.; Hou, W.H.; Hsieh, C.L. Evaluating the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire in Patients with Stroke: A Latent Trait Analysis Using Rasch Modeling. Patient 2018, 11, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrich, D. Rating scales and Rasch measurement. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2011, 11, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, A.; Conaghan, P.G. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: What is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Rheumatol. 2007, 57, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallant, J.F.; Tennant, A. An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: An example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó-Cerdán, M.; Cacho-Martínez, P.; Lara-Lacárcel, F.; García-Muñoz, Á. Rasch analysis for development and reduction of Symptom Questionnaire for Visual Dysfunctions (SQVD). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vet, H.; Terwee, C.; Mokkink, L.; Knol, D. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 1–338. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, A.; Pallant, J. Unidimensionality matters! (A tale of two Smiths?). Rasch Meas. Trans. 2006, 20, 1048–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Andrich, D.; Marais, I. A Course in Rasch Measurement Theory: Measuring in the Educational, Social and Health Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dzingina, M.; Higginson, I.J.; McCrone, P.; Murtagh, F.E.M. Development of a Patient-Reported Palliative Care-Specific Health Classification System: The POS-E. Patient 2017, 10, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.A. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2014, 34, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.; Mukuria, C.; Mulhern, B.; Tran, I.; Brazier, J.; Watson, S. Measuring the Burden of Schizophrenia Using Clinician and Patient-Reported Measures: An Exploratory Analysis of Construct Validity. Patient 2019, 12, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellema, S.; Wijnen, M.A.M.; Steultjens, E.M.J.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; van der Sande, R. Valued activities and informal caregiving in stroke: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 2223–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Campos, A.; Compañ-Gabucio, L.-M.; Torres-Collado, L.; Garcia-de la Hera, M. Occupational Therapy Interventions for Dementia Caregivers: Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Diego-Alonso, C.; Bellosta-López, P.; Hultqvist, J.; Vidaña-Moya, L.; Eklund, M. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Satisfaction with Daily Occupations and Occupational Balance in Spanish Stroke Survivors. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 78, 7803205050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonett, D.G.; Wright, T.A. Cronbach’s alpha reliability Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ruth, Z.; Linda, L.; Gray, J.M. Occupational harmony: Embracing the complexity of occupational balance. J. Occup. Sci. 2023, 30, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.D.L.; John, M. Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 8, 370. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, W.J.; Staver, J.R.; Yale, M.S. Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.B.; Rush, R.; Fallowfield, L.J.; Velikova, G.; Sharpe, M. Rasch fit statistics and sample size considerations for polytomous data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud, J.A.; Geese, F.; Uhlmann, K.; Blasimann, A.; Wagner, F.L.; Neubauer, F.B.; Huwendiek, S.; Hahn, S.; Schmitt, K.-U. Mixed methods instrument validation: Evaluation procedures for practitioners developed from the validation of the Swiss Instrument for Evaluating Interprofessional Collaboration. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, I. Understanding Differential Item Functioning and Item bias In Psychological Instruments. PPRS 2018, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Nagl-Cupal, M.; Kolland, F.; Zartler, U.; Bittner, M.; Koller, M.; Parisot, V.; Stöhr, D. Angehörigenpflege in Österreich: Einsicht in Die Situation Pflegender Angehöriger Und in Die Entwicklung Informeller Pflegenetzwerke; Bundesministerium Für Arbeit, Soziales, Gesundheit Und Konsumentenschutz: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saragosa, M.; Frew, M.; Hahn-Goldberg, S.; Orchanian-Cheff, A.; Abrams, H.; Okrainec, K. The Young Carers’ Journey: A Systematic Review and Meta Ethnography. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, K.B.; Kreiner, S.; Mesbah, M. Rasch Models in Health; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Altomonte, G. Beyond Being on Call: Time, Contingency, and Unpredictability Among Family Caregivers for the Elderly. Sociol. Forum 2016, 31, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K. The Tensions between Process Time and Clock Time in Care-Work: The Example of Day Nurseries. Time Soc. 1994, 3, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, T.; Andrea, G.; Agatha, S.; Lemyre, L. “We Don’t Have a Back-Up Plan”: An Exploration of Family Contingency Planning for Emergencies Following Stroke. Soc. Work Health Care 2012, 51, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissmark, S.; Fänge, A. Occupational balance among family members of people in palliative care. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 27, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watford, P.; Jewell, V.; Atler, K. Increasing Meaningful Occupation for Women Who Provide Care for Their Spouse: A Pilot Study. OTJR 2019, 39, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, J.D.; Singh, G.; Kaur, P.; Bansal, R.; Paul, B.S.; Singla, M.; Singh, S.; Samuel, C.J.; Verma, S.J.; Moodbidri, P.; et al. Incidence, short-term outcome, and spatial distribution of stroke patients in Ludhiana, India. Neurology 2016, 86, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.-J.; Zhao, K.; Fils-Aime, F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyab, W.e.; Ferguson, C.; Rolls, K.; Halcomb, E. Solutions to address low response rates in online surveys. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2023, 22, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, C.; Andersson, S.; Kylén, M.; Iwarsson, S.; Hanson, E.; Schmidt, S.M. What motivates informal carers to be actively involved in research, and what obstacles to involvement do they perceive? Res. Involv. Engagem. 2021, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkamp, M.; Wittek, R.P.M.; Hagedoorn, M.; Stolk, R.P.; Smidt, N. Survey nonresponse among informal caregivers: Effects on the presence and magnitude of associations with caregiver burden and satisfaction. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, H.; French, B.F. A Comparison of Estimation Techniques for IRT Models With Small Samples. Appl. Meas. Educ. 2019, 32, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subscale 1 | Subscale 2 | Subscale 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Eigenvalue | Item | Eigenvalue | Item | Eigenvalue | ||||||

| Total | % of VA | CUM % | Total | % of VA | CUM % | Total | % of VA | CUM % | |||

| 1_a | 4.55 | 50.58 | 50.58 | 2_a | 3.93 | 56.20 | 56.20 | 3_a | 3.74 | 62.25 | 62.25 |

| 1_b | 0.95 | 10.52 | 61.10 | 2_b | 0.83 | 11.88 | 68.08 | 3_b | 0.81 | 13.42 | 75.67 |

| 1_c | 0.71 | 7.86 | 68.96 | 2_c | 0.59 | 8.37 | 76.45 | 3_c | 0.56 | 9.28 | 84.95 |

| 1_d | 0.63 | 7.00 | 75.96 | 2_d | 0.56 | 7.94 | 84.39 | 3_d | 0.37 | 6.12 | 91.06 |

| 1_e | 0.53 | 5.93 | 81.89 | 2_e | 0.43 | 6.15 | 90.54 | 3_e | 0.33 | 5.47 | 96.53 |

| 1_f | 0.46 | 5.14 | 87.03 | 2_f | 0.36 | 5.14 | 95.67 | 3_f | 0.21 | 3.47 | 100.00 |

| 1_g | 0.44 | 4.93 | 91.96 | 2_g | 0.30 | 4.33 | 100.00 | ||||

| 1_h | 0.38 | 4.27 | 96.23 | ||||||||

| 1_i | 0.34 | 3.77 | 100.00 | ||||||||

| Subscale 1 | Inter-Item Correlation | Total–Item Correlation | |||||||||

| 1_a | 1_b | 1_c | 1_d | 1_e | 1_f | 1_g | 1_h | 1_i | |||

| 1_a | 1.00 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1_a | 0.65 |

| 1_b | 0.51 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 1_b | 0.69 |

| 1_c | 0.47 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 1_c | 0.69 |

| 1_d | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 1_d | 0.73 |

| 1_e | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 1_e | 0.72 |

| 1_f | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 1_f | 0.78 |

| 1_g | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 1_g | 0.73 |

| 1_h | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 1_h | 0.67 |

| 1_i | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 1_i | 0.73 |

| Subscale 2 | Inter-Item Correlation | Total–Item Correlation | |||||||||

| 2_a | 2_b | 2_c | 2_d | 2_e | 2_f | 2_g | |||||

| 2_a | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 2_a | 0.71 | ||

| 2_b | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 2_b | 0.74 | ||

| 2_c | 0.41 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 2_c | 0.71 | ||

| 2_d | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 2_d | 0.79 | ||

| 2_e | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.65 | 2_e | 0.76 | ||

| 2_f | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 2_f | 0.72 | ||

| 2_g | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 1.00 | 2_g | 0.82 | ||

| Subscale 3 | Inter-Item Correlation | Total–Item Correlation | |||||||||

| 3_a | 3_b | 3_c | 3_d | 3_e | 3_f | ||||||

| 3_a | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 3_a | 0.78 | |||

| 3_b | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 3_b | 0.82 | |||

| 3_c | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 3_c | 0.78 | |||

| 3_d | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 3_d | 0.74 | |||

| 3_e | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 3_e | 0.83 | |||

| 3_f | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 3_f | 0.79 | |||

| Subscale 1 | Location | SE | Av. residual |

| 1_a | 0.66 | 0.10 | 1.33 × 10−4 |

| 1_b | 0.72 | 0.10 | 1.35 × 10−4 |

| 1_c | 0.24 | 0.10 | 1.19 × 10−4 |

| 1_d | −0.26 | 0.10 | 2.09 × 10−5 |

| 1_e | −0.10 | 0.10 | 2.17 × 10−5 |

| 1_f | −0.72 | 0.10 | 4.12 × 10−5 |

| 1_g | −0.37 | 0.10 | 2.03 × 10−5 |

| 1_h | 0.03 | 0.10 | 1.08 × 10−4 |

| 1_i | 0.04 | 0.10 | 1.08 × 10−4 |

| Subscale 2 | Location | SE | Av. residual |

| 2_a | −0.15 | 0.11 | 1.29 × 10−4 |

| 2_b | −0.36 | 0.11 | 1.41 × 10−4 |

| 2_c | −0.08 | 0.11 | 5.91 × 10−6 |

| 2_d | −0.22 | 0.11 | 1.33 × 10−4 |

| 2_e | 0.45 | 0.11 | 2.58 × 10−6 |

| 2_f | 0.70 | 0.11 | 1.25 × 10−6 |

| 2_g | 0.59 | 0.11 | 1.83 × 10−6 |

| Subscale 3 | Location | SE | Av. residual |

| 2_a | −0.05 | 0.11 | 1.60 × 10−5 |

| 2_b | −0.08 | 0.11 | 2.23 × 10−5 |

| 2_c | 0.24 | 0.11 | 9.37 × 10−5 |

| 2_d | 0.01 | 0.11 | 8.79 × 10−5 |

| 2_e | 0.01 | 0.11 | 8.79 × 10−5 |

| 2_f | −0.41 | 0.11 | 1.47 × 10−5 |

| Subscale 1 | Infit | Outfit | Subscale 2 | Infit | Outfit | Subscale 3 | Infit | Outfit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1_a | 0.85 | 0.85 | 2_a | 1.06 | 1.08 | 3_a | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| 1_b | 0.93 | 0.93 | 2_b | 1.16 | 1.14 | 3_b | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| 1_c | 0.90 | 0.91 | 2_c | 0.90 | 0.93 | 3_c | 0.88 | 0.90 |

| 1_d | 1.06 | 1.05 | 2_d | 0.95 | 0.94 | 3_d | 1.10 | 1.08 |

| 1_e | 1.17 | 1.16 | 2_e | 0.94 | 0.94 | 3_e | 1.06 | 1.04 |

| 1_f | 0.87 | 0.85 | 2_f | 1.29 | 1.27 | 3_f | 1.22 | 1.20 |

| 1_g | 0.90 | 0.90 | 2_g | 0.73 | 0.72 | |||

| 1_h | 1.39 | 1.35 | ||||||

| 1_i | 0.99 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schön, M.; Lischka, C.; Köttl, H.; Fallahpour, M.; Guidetti, S.; Baciu, L.; Lentner, S.; Haberl, E.; Dür, M. Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the German Version of OBI-Care in Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176270

Schön M, Lischka C, Köttl H, Fallahpour M, Guidetti S, Baciu L, Lentner S, Haberl E, Dür M. Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the German Version of OBI-Care in Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176270

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchön, Michael, Cornelia Lischka, Hanna Köttl, Mandana Fallahpour, Susanne Guidetti, Larisa Baciu, Stefanie Lentner, Evelyn Haberl, and Mona Dür. 2025. "Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the German Version of OBI-Care in Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176270

APA StyleSchön, M., Lischka, C., Köttl, H., Fallahpour, M., Guidetti, S., Baciu, L., Lentner, S., Haberl, E., & Dür, M. (2025). Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the German Version of OBI-Care in Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176270