Alcohol Use Disorder—Stress, Sense of Coherence, and Its Impact on Satisfaction with Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Analyzing the relationships between the sense of coherence and its dimensions and the level of perceived stress, the level of health behaviors, the level of acceptance of illness, and satisfaction with life while controlling for participants’ age;

- To determine if the level of perceived stress and health behaviors were parallel mediators of the relationships between the sense of coherence and both satisfaction with life and acceptance of illness, while controlling for participants’ age.

Descriptive Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Sense of Coherence as a Predictor of Perceived Stress, Health Behaviors, Acceptance of Illness, and Satisfaction with Life

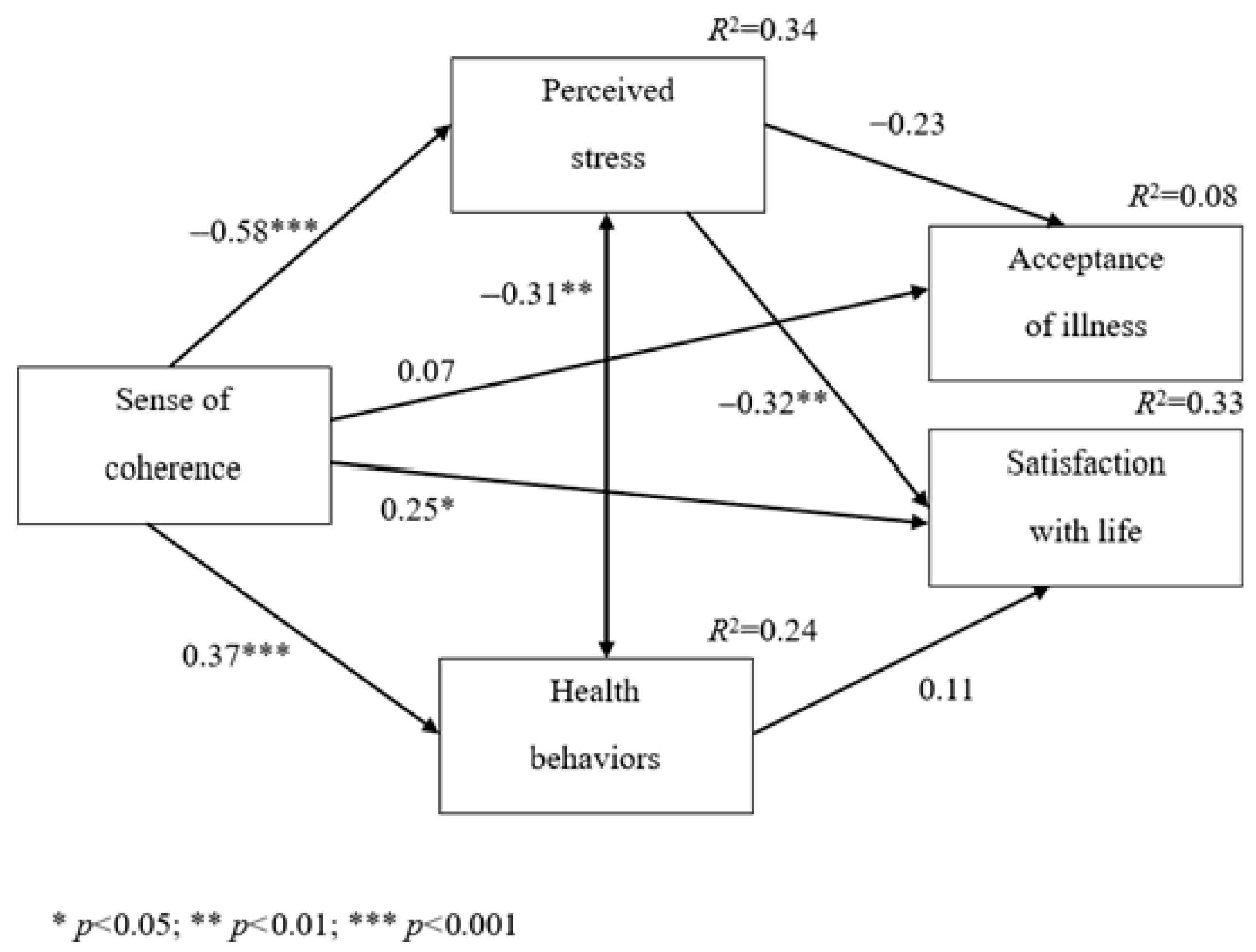

3.2. Perceived Stress and Health Behaviors as Mediators of the Relationships Between the Sense of Coherence and Satisfaction with Life or Satisfaction with Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grevenstein, D.; Bluemke, M.; Nagy, E.; Wippermann, C.; Jungaberle, H. Sense of coherence and substance use: Examining mutual influences. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 64, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, A.S.; Willroth, E.C.; Shallcross, A.J.; Giuliani, N.R.; Gross, J.J.; Mauss, I.B. Psychological Resilience: An Affect-Regulation Framework. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 547–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky, A. The Sense of Coherence: Development of a Research Instrument; Newsletter Research Report; Schwartz Research Center for Behavioral Medicine, Tel Aviv University: Tel Aviv, Israel, 1983; Volume 1, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, N.; Surtees, P.; Welch, A.; Luben, R.; Khaw, K.T.; Bingham, S. Healthy lifestyle choices: Could sense of coherence aid health promotion? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michałowska, S.; Bogucka, M. Sense of coherence, general self-efficacy and health behaviors in women after mastectomy. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 23, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarit, S.; Rajesh, G.; Eriksson, M.; Pai, M. Impact of Sense of Coherence on Oral Health Behaviour and Perceived Stress among a Rural Population in South India- An Exploratory Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2020, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curyło, M.; Rynkiewicz-Andryśkiewicz, M.; Andryśkiewicz, P.; Mikos, M.; Lusina, D.; Raczkowski, J.W.; Partyka, O.; Pajewska, M.; Sygit, K.; Sygit, M.; et al. Acceptance of Illness and Coping with Stress among Patients Undergoing Alcohol Addiction Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curyło, M.; Czerw, A.; Rynkiewicz-Andryśkiewicz, M.; Andryśkiewicz, P.; Mikos, M.; Partyka, O.; Pajewska, M.; Świtalski, J.; Sygit, K.; Sygit, M.; et al. Measuring the Intensity of Stress Experienced and Its Impact on Life in Patients with Diagnosed Alcohol Use Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyniak-Cieciura, M. Stress, satisfaction with life and general health in a relationship to health behaviors: The moderating role of temperament structures. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 52, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Connor-Smith, J. Personality and coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moksnes, U.K. Sense of Coherence. In Health Promotion in Health Care—Vital Theories and Research [Internet]; Haugan, G., Eriksson, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Chapter 4. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585678/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/health-topics/alcohol#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230201-1 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Iwanicka, K.A.; Olajossy, M. The concept of alcohol craving. Psychiatr. Polska 2015, 49, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik-Koncewicz, K. Exposure of the Polish population to alcohol. Alcohol-related health harm, its causes and possible solutions. J. Health Inequal. 2024, 10, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsior, K.; Biedrzycka, A.; Chodkiewicz, J.; Ziółkowski, M.; Czarnecki, D.; Juczyński, A.; Nowakowska-Domagała, K. Alcohol craving in relation to coping with stress and satisfaction with life in the addicted. Health Psychol. Rep. 2016, 4, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeli, S.; Sullivan, T.P.; Tennen, H. Drinking to Cope Motivation as a Prospective Predictor of Negative Affect. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2015, 76, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthenelli, R.; Grandison, L. Effects of stress on alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res. 2012, 34, 381–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, M. The Sense of Coherence in the Salutogenic Model of Health. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.N., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Chapter 11. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435812/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Juczynski, Z.; Oginska-Bulik, N. Tools for Measuring Stress and Coping with Stress; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Juczynski, Z. NPPPZ—Narz ędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych, Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Comm. Health 2006, 60, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M. The Sense of Coherence: The Concept and Its Relationship to Health. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Mittelmark, M.B., Bauer, G.F., Vaandrager, L., Pelikan, J.M., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Lindström, B., Magistretti, C.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, S.K.; Sopp, M.R.; Fuchs, A.; Kotzur, M.; Maahs, L.; Michael, T. The relationship between sense of coherence and mental health problems from childhood to young adulthood: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 325, 804–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, E.; Jones, A.; Field, M. Acute stress increases ad-libitum alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers, but not through impaired inhibitory control. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, H.C. Effects of alcohol dependence and withdrawal on stress responsiveness and alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res. 2012, 34, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | Min | Max | S | K | S-W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with life | 17.10 | 5.61 | 5 | 33 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 0.133 |

| Comprehensibility | 40.15 | 8.55 | 20 | 60 | 0.04 | −0.22 | 0.99 | 0.650 |

| Manageability | 43.29 | 7.86 | 19 | 61 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.807 |

| Meaningfulness | 36.93 | 7.99 | 14 | 54 | −0.41 | 0.08 | 0.98 | 0.266 |

| Sense of coherence | 120.37 | 21.02 | 54 | 169 | −0.19 | 0.50 | 0.99 | 0.751 |

| Perceived stress | 20.47 | 7.11 | 1 | 36 | −0.07 | −0.48 | 0.98 | 0.248 |

| Positive mental attitude | 20.09 | 3.95 | 10 | 30 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.463 |

| Preventive behavior | 19.27 | 5.06 | 6 | 29 | −0.24 | −0.33 | 0.98 | 0.199 |

| Correct eating habits | 17.88 | 4.78 | 8 | 27 | 0.03 | −0.89 | 0.97 | 0.038 |

| Health practices | 18.31 | 4.40 | 6 | 27 | 0.06 | −0.29 | 0.98 | 0.062 |

| Health behaviors | 75.55 | 14.41 | 31 | 104 | −0.38 | −0.12 | 0.98 | 0.187 |

| Acceptance of illness | 27.65 | 7.22 | 10 | 40 | −0.43 | −0.60 | 0.97 | 0.011 |

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. Satisfaction with life | 0.086 | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Comprehensibility | 0.219 * | 0.415 ** | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Manageability | 0.190 | 0.374 ** | 0.651 ** | -- | ||||||||

| 5. Meaningfulness | 0.120 | 0.469 ** | 0.600 ** | 0.585 ** | -- | |||||||

| 6. Sense of coherence | 0.206 * | 0.487 ** | 0.878 ** | 0.861 ** | 0.843 ** | -- | ||||||

| 7. Perceived stress | −0.046 | −0.520 ** | −0.483 ** | −0.523 ** | −0.493 ** | −0.579 ** | -- | |||||

| 8. Positive mental attitude | 0.256 * | 0.484 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.540 ** | 0.532 ** | −0.566 ** | -- | ||||

| 9. Preventive behavior | 0.221 * | 0.218 * | 0.198 * | 0.064 | 0.372 ** | 0.246 * | −0.294 ** | 0.564 ** | -- | |||

| 10. Correct eating habits | 0.247 * | 0.232 * | 0.379 ** | 0.210 * | 0.344 ** | 0.363 ** | −0.299 ** | 0.386 ** | 0.580 ** | -- | ||

| 11. Health practices | 0.253 * | 0.246 * | 0.290 ** | 0.126 | 0.201 * | 0.242 * | −0.300 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.501 ** | -- | |

| 12. Health behaviors | 0.307 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.402 ** | 0.242 * | 0.454 ** | 0.427 ** | −0.450 ** | 0.737 ** | 0.851 ** | 0.795 ** | 0.770 ** | -- |

| 13. Acceptance of illness | −0.008 | 0.165 | 0.194 | 0.175 | 0.146 | 0.200 * | −0.268 ** | 0.070 | 0.035 | 0.127 | 0.069 | 0.094 |

| Dependent Variable | Predictor | Beta | p | VIF | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived | Comprehensibility | −0.17 | 0.146 | 20.02 | 0.317 |

| stress | Manageability | −0.29 | 0.014 | 10.94 | |

| Meaningfulness | −0.23 | 0.040 | 10.75 | ||

| Positive | Comprehensibility | 0.10 | 0.415 | 20.02 | 0.340 |

| mental | Manageability | 0.06 | 0.593 | 10.94 | |

| attitude | Meaningfulness | 0.42 | 0.001 | 10.75 | |

| Preventive | Comprehensibility | 0.05 | 0.689 | 20.02 | 0.219 |

| behavior | Manageability | −0.30 | 0.022 | 10.94 | |

| Meaningfulness | 0.49 | 0.001 | 10.75 | ||

| Correct | Comprehensibility | 0.30 | 0.023 | 20.02 | 0.206 |

| eating | Manageability | −0.16 | 0.222 | 10.94 | |

| habits | Meaningfulness | 0.23 | 0.057 | 10.75 | |

| Health | Comprehensibility | 0.29 | 0.035 | 20.02 | 0.136 |

| Practices | Manageability | −0.16 | 0.239 | 10.94 | |

| Meaningfulness | 0.09 | 0.456 | 10.75 | ||

| Health | Comprehensibility | 0.23 | 0.058 | 20.02 | 0.303 |

| Behaviors | Manageability | −0.19 | 0.122 | 10.94 | |

| Meaningfulness | 0.39 | 0.001 | 10.75 | ||

| Acceptance | Comprehensibility | 0.14 | 0.325 | 20.02 | 0.045 |

| of illness | Manageability | 0.08 | 0.556 | 10.94 | |

| Meaningfulness | 0.02 | 0.878 | 10.75 | ||

| Satisfaction | Comprehensibility | 0.18 | 0.168 | 20.02 | 0.250 |

| with life | Manageability | 0.07 | 0.558 | 10.94 | |

| Meaningfulness | 0.32 | 0.007 | 10.75 |

| Dependent Variable | Beta | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived stress | −0.60 | 0.001 | 0.341 |

| Positive mental attitude | 0.50 | 0.001 | 0.306 |

| Preventive behavior | 0.21 | 0.037 | 0.091 |

| Correct eating habits | 0.33 | 0.001 | 0.163 |

| Health practices | 0.20 | 0.047 | 0.101 |

| Health behaviors | 0.38 | 0.001 | 0.232 |

| Acceptance of illness | 0.21 | 0.040 | 0.043 |

| Satisfaction with life | 0.49 | 0.001 | 0.237 |

| Predictors | Endogenous Variables | Beta | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of coherence | Perceived stress | −0.58 | <0.001 |

| Sense of coherence | Health behaviors | 0.37 | <0.001 |

| Perceived stress | Acceptance of illness | −0.23 | 0.052 |

| Sense of coherence | Acceptance of illness | 0.07 | 0.567 |

| Perceived stress | Satisfaction with life | −0.32 | 0.002 |

| Health behaviors | Satisfaction with life | 0.11 | 0.249 |

| Sense of coherence | Satisfaction with life | 0.25 | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pajewska, M.; Partyka, O.; Czerw, A.; Sygit, K.; Wojtyła-Buciora, P.; Porada, S.; Gąska, I.; Konieczny, M.; Grochans, E.; Cybulska, A.M.; et al. Alcohol Use Disorder—Stress, Sense of Coherence, and Its Impact on Satisfaction with Life. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176183

Pajewska M, Partyka O, Czerw A, Sygit K, Wojtyła-Buciora P, Porada S, Gąska I, Konieczny M, Grochans E, Cybulska AM, et al. Alcohol Use Disorder—Stress, Sense of Coherence, and Its Impact on Satisfaction with Life. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176183

Chicago/Turabian StylePajewska, Monika, Olga Partyka, Aleksandra Czerw, Katarzyna Sygit, Paulina Wojtyła-Buciora, Sławomir Porada, Izabela Gąska, Magdalena Konieczny, Elżbieta Grochans, Anna Maria Cybulska, and et al. 2025. "Alcohol Use Disorder—Stress, Sense of Coherence, and Its Impact on Satisfaction with Life" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176183

APA StylePajewska, M., Partyka, O., Czerw, A., Sygit, K., Wojtyła-Buciora, P., Porada, S., Gąska, I., Konieczny, M., Grochans, E., Cybulska, A. M., Schneider-Matyka, D., Bandurska, E., Ciećko, W., Drobnik, J., Pobrotyn, P., Waśko-Czopnik, D., Pobrotyn, J., Wiatkowski, A., Strzępek, Ł., ... Kozlowski, R. (2025). Alcohol Use Disorder—Stress, Sense of Coherence, and Its Impact on Satisfaction with Life. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176183