Clinical Management of Gingival Recessions with or Without Cervical Lesions: A Decisional Scheme Proposal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods: Decisional Tree Proposal

2.1. Periodontal Evaluation

2.2. Hard Dental Tissue Evaluation (Crown and Root Assessment)

3. Results

Case Reports

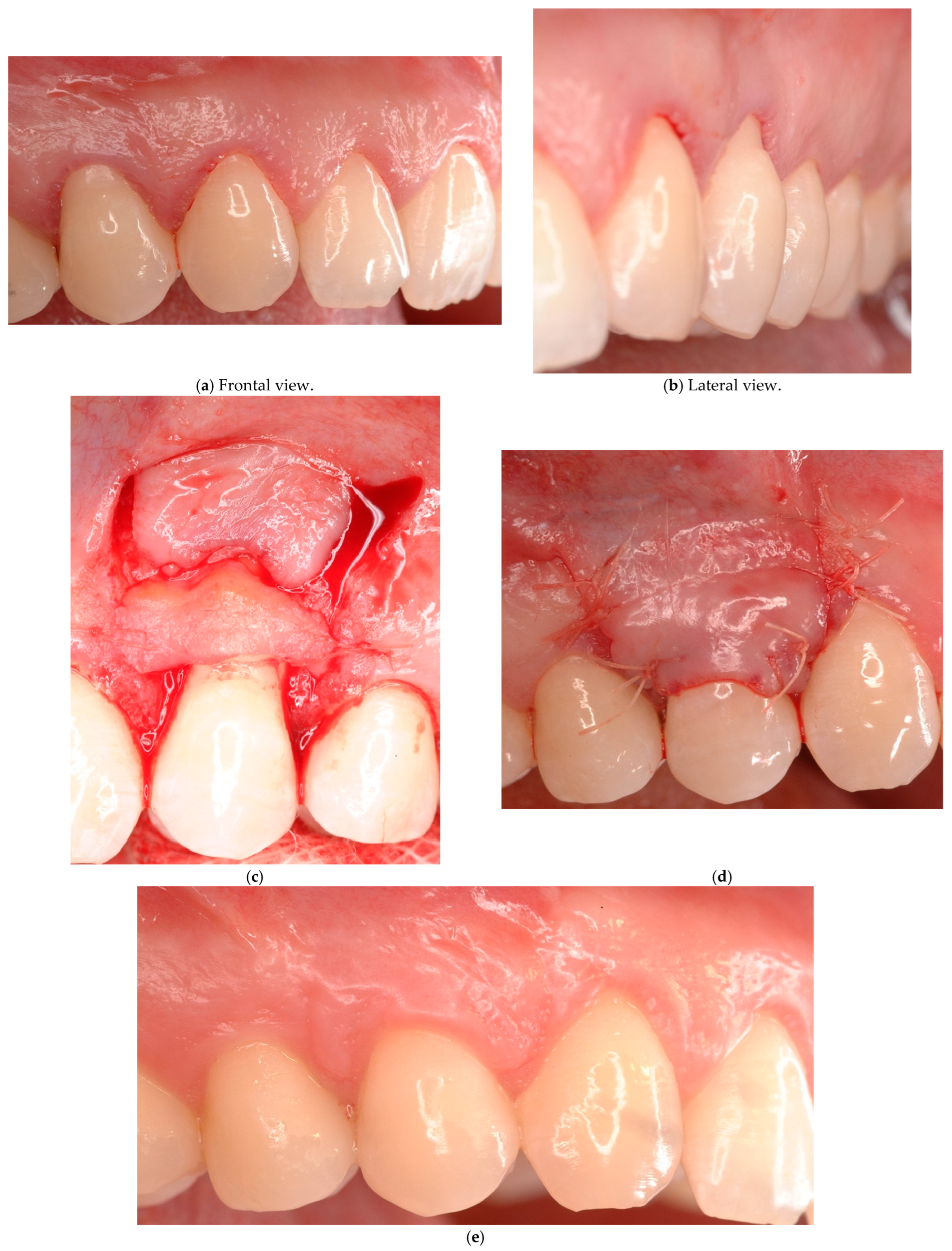

- Case # 1: Identifiable CEJ without non-carious cervical lesion (Class A−).

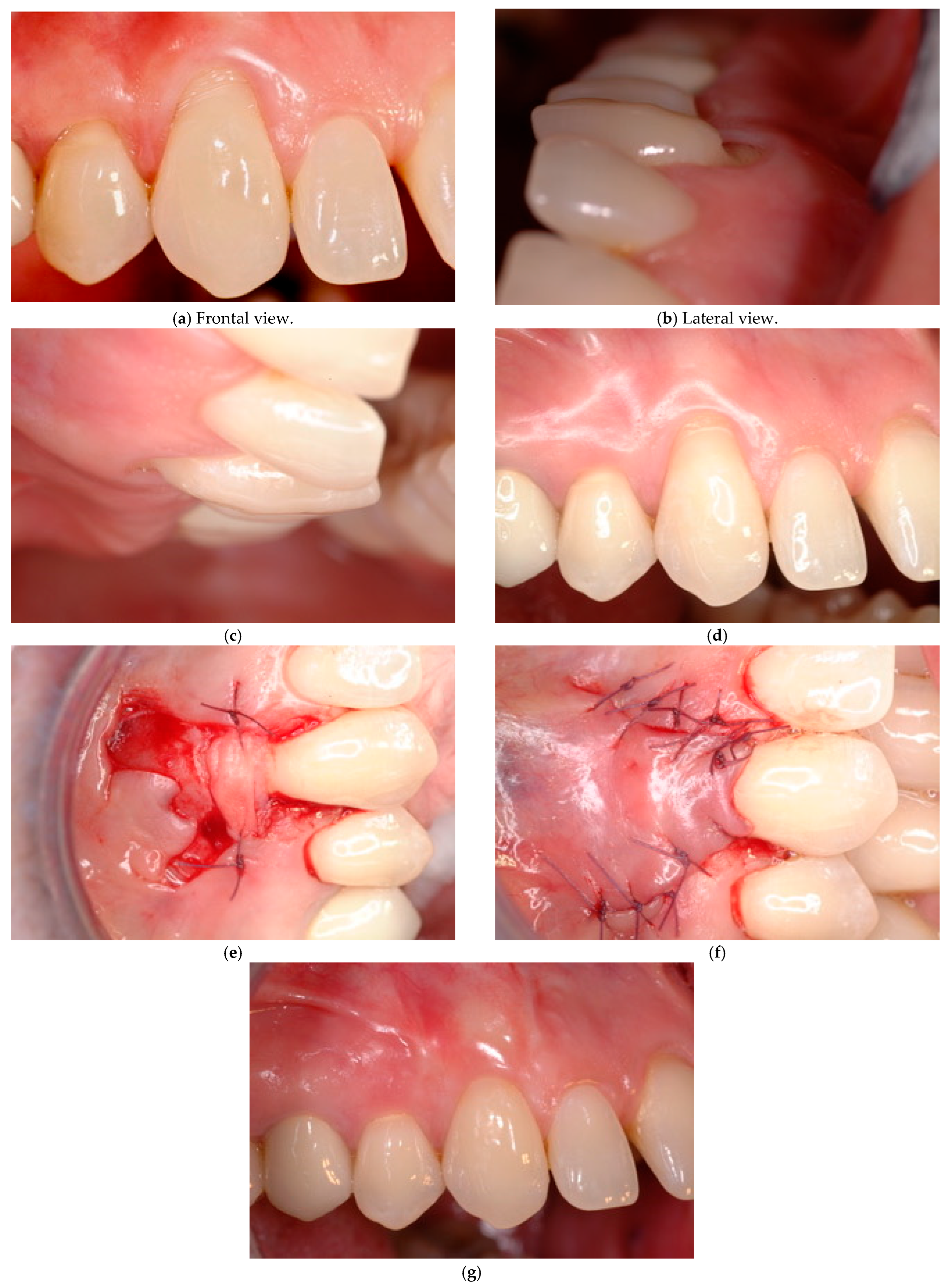

- Case # 2: Identifiable CEJ with non-carious cervical lesion (Class A+).

- Case # 3: Unidentifiable CEJ without non-carious cervical lesion (Class B−).

- Case # 4: Unidentifiable CEJ with non-carious cervical lesion (B+).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAF | Coronally advanced flap |

| CEJ | Cemento-enamel junction |

| CRC | Complete root coverage |

| CTG | Connective tissue graft |

| IA | Interdental attachment |

| KT | Keratinized tissue |

| KTW | Width of keratinized tissue |

| LCT | Laterally closed tunnel |

| NCCL | Non-carious cervical lesion |

| RT | Recession type |

| TUN | Tunnel technique |

References

- Chambrone, L.; Ortega, M.A.S.; Sukekava, F.; Rotundo, R.; Kalemaj, Z.; Buti, J.; Prato, G.P.P. Root Coverage Procedures for Treating Single and Multiple Recession-Type Defects: An Updated Cochrane Systematic Review. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 1399–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, F.; Cortellini, P.; Tonetti, M.; Nieri, M.; Mervelt, J.; Pagavino, G.; Pini-Prato, G.P. Stability of Root Coverage Outcomes at Single Maxillary Gingival Recession with Loss of Interdental Attachment: 3-Year Extension Results from a Randomized, Controlled, Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Oduncuoğlu, B.F.; Nişancı Yılmaz, M.N. Evaluation of Patients’ Perception of Gingival Recession, Its Impact on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, and Acceptance of Treatment Plan. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, P.; Daing, A.; Azam, I.; Miglani, R.; Bhardwaj, A. Impact of Altered Gingival Characteristics on Smile Esthetics: Laypersons’ Perspectives by Q Sort Methodology. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 154, 82–90.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, R.; Nieri, M.; Bonaccini, D.; Mori, M.; Lamberti, E.; Massironi, D.; Giachetti, L.; Franchi, L.; Venezia, P.; Cavalcanti, R.; et al. The Smile Esthetic Index (SEI): A Method to Measure the Esthetics of the Smile. An Intra-Rater and Inter-Rater Agreement Study. Eur. J. Oral. Implantol. 2015, 8, 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Musskopf, M.L.; Rocha, J.M.d.; Rösing, C.K. Perception of Smile Esthetics Varies between Patients and Dental Professionals When Recession Defects Are Present. Braz. Dent. J. 2013, 24, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speroni, S.; Antonelli, L.; Coccoluto, L.; Giuffrè, M.; Zucchelli, A.; Sarnelli, F.; Ronsivalle, V.; Zucchelli, G. The Prosthetic Rehabilitation of Maxillary Aesthetic Area Guided by a Multidisciplinary Approach: A Case Report with Histomorphometric Evaluation. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, F.; Rotundo, R.; Miller, P.D.; Pini Prato, G.P. Root Coverage Esthetic Score: A System to Evaluate the Esthetic Outcome of the Treatment of Gingival Recession through Evaluation of Clinical Cases. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, S.; Caton, J.G.; Albandar, J.M.; Bissada, N.F.; Bouchard, P.; Cortellini, P.; Demirel, K.; de Sanctis, M.; Ercoli, C.; Fan, J.; et al. Periodontal Manifestations of Systemic Diseases and Developmental and Acquired Conditions: Consensus Report of Workgroup 3 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S237–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Periodontology. Glossary of Periodontal Terms, 5th ed.; American Academy of Periodontology: Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chambrone, L.; Salinas Ortega, M.A.; Sukekava, F.; Rotundo, R.; Kalemaj, Z.; Buti, J.; Pini Prato, G.P. Root Coverage Procedures for Treating Localised and Multiple Recession-Type Defects. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD007161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, F.; Pini-Prato, G.P. A Technique to Identify and Reconstruct the Cementoenamel Junction Level Using Combined Periodontal and Restorative Treatment of Gingival Recession. A Prospective Clinical Study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2010, 30, 573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchelli, G.; Testori, T.; De Sanctis, M. Clinical and Anatomical Factors Limiting Treatment Outcomes of Gingival Recession: A New Method to Predetermine the Line of Root Coverage. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imber, J.-C.; Kasaj, A. Treatment of Gingival Recession: When and How? Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.W.; Shah, P. A Critical Review of Non-Carious Cervical (Wear) Lesions and the Role of Abfraction, Erosion, and Abrasion. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellver-Fernández, R.; Martínez-Rodriguez, A.-M.; Gioia-Palavecino, C.; Caffesse, R.-G.; Peñarrocha, M. Surgical Treatment of Localized Gingival Recessions Using Coronally Advanced Flaps with or without Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e222–e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambrone, L.; Sukekava, F.; Araújo, M.G.; Pustiglioni, F.E.; Chambrone, L.A.; Lima, L.A. Root-Coverage Procedures for the Treatment of Localized Recession-Type Defects: A Cochrane Systematic Review. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 452–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, M.P.; Suaid, F.F.; Casati, M.Z.; Nociti, F.H.; Sallum, A.W.; Sallum, E.A. Coronally Positioned Flap plus Resin-Modified Glass Ionomer Restoration for the Treatment of Gingival Recession Associated with Non-Carious Cervical Lesions: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, M.P.; Suaid, F.F.; Nociti, F.H.; Casati, M.Z.; Sallum, A.W.; Sallum, E.A. Periodontal Surgery and Glass Ionomer Restoration in the Treatment of Gingival Recession Associated with a Non-Carious Cervical Lesion: Report of Three Cases. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavelli, L.; Barootchi, S.; Nguyen, T.V.N.; Tattan, M.; Ravidà, A.; Wang, H.-L. Efficacy of Tunnel Technique in the Treatment of Localized and Multiple Gingival Recessions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculean, A.; Allen, E.P. The Laterally Closed Tunnel for the Treatment of Deep Isolated Mandibular Recessions: Surgical Technique and a Report of 24 Cases. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2018, 38, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rouck, T.; Eghbali, R.; Collys, K.; De Bruyn, H.; Cosyn, J. The gingival biotype revisited: Transparency of the periodontal probe through the gingival margin as a method to discriminate thin from thick gingiva. J Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, F.; Nieri, M.; Cincinelli, S.; Mervelt, J.; Pagliaro, U. The Interproximal Clinical Attachment Level to Classify Gingival Recessions and Predict Root Coverage Outcomes: An Explorative and Reliability Study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini-Prato, G.; Franceschi, D.; Cairo, F.; Nieri, M.; Rotundo, R. Classification of Dental Surface Defects in Areas of Gingival Recession. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambrone, L.; Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Mascarenhas, P.; Mendes, J.J.; Avila-Ortiz, G. Does the Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft in Conjunction with a Coronally Advanced Flap Remain as the Gold Standard Therapy for the Treatment of Single Gingival Recession Defects? A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 1336–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Coronado, T.; Hernández-Juárez, E.; Gutiérrez-Rivas, D.E.; Garza-Enríquez, M.; Martínez-Sandoval, G.; Baltazar-Ruiz, A. Coronally Advanced Flap with Connective Tissue Graft for the Treatment of Multiple Recession Defects: Case Report. Int. J. Interdiscip. Dent. 2024, 17, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchelli, G.; Marzadori, M.; Mounssif, I.; Mazzotti, C.; Stefanini, M. Coronally Advanced Flap + Connective Tissue Graft Techniques for the Treatment of Deep Gingival Recession in the Lower Incisors. A Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchelli, G.; Tavelli, L.; Ravidà, A.; Stefanini, M.; Suárez-López Del Amo, F.; Wang, H.-L. Influence of Tooth Location on Coronally Advanced Flap Procedures for Root Coverage. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.P.; Miller, P.D. Coronal Positioning of Existing Gingiva: Short Term Results in the Treatment of Shallow Marginal Tissue Recession. J. Periodontol. 1989, 60, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernimoulin, J.P.; Lüscher, B.; Mühlemann, H.R. Coronally Repositioned Periodontal Flap. Clinical Evaluation after One Year. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1975, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, J.S.; Heller, R. Histologic Evaluation of Full and Partial Thickness Lateral Repositioned Flaps: A Pilot Study. J. Periodontol. 1971, 42, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffileno, H. Management of Gingival Recession and Root Exposure Problems Associated with Periodontal Disease. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1964, 8, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupe, H.E.; Warren, R.F. Repair of Gingival Defects by a Sliding Flap Operation. J. Periodontol. 1956, 27, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.W.; Ross, S.E. The Double Papillae Repositioned Flap in Periodontal Therapy. J. Periodontol. 1968, 39, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchelli, G.; Cesari, C.; Amore, C.; Montebugnoli, L.; De Sanctis, M. Laterally Moved, Coronally Advanced Flap: A Modified Surgical Approach for Isolated Recession-Type Defects. J. Periodontol. 2004, 75, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, B.; Langer, L. Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft Technique for Root Coverage. J. Periodontol. 1985, 56, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.W. The Subpedicle Connective Tissue Graft. A Bilaminar Reconstructive Procedure for the Coverage of Denuded Root Surfaces. J. Periodontol. 1987, 58, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.J. The Connective Tissue and Partial Thickness Double Pedicle Graft: A Predictable Method of Obtaining Root Coverage. J. Periodontol. 1992, 63, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.F. Connective Tissue Graft Technique Assuring Wide Root Coverage. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 1994, 14, 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pini Prato, G.P.; Baldi, C.; Nieri, M.; Franseschi, D.; Cortellini, P.; Clauser, C.; Rotundo, R.; Muzzi, L. Coronally Advanced Flap: The Post-Surgical Position of the Gingival Margin Is an Important Factor for Achieving Complete Root Coverage. J. Periodontol. 2005, 76, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovoor, K.L.; Attavar, S.H. Comparative Evaluation of the Surface Roughness of a Microhybrid and Nanohybrid Composites Using Various Polishing System: A Profilometric Analysis. J. Int. Oral. Health 2023, 15, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Pajares, S.P.; Koi, K.; Watanabe, H.; da Costa, J.B.; Ferracane, J.L. Development and Maintenance of Surface Gloss of Dental Composites after Polishing and Brushing: Review of the Literature. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, J.A.; Santos, V.R.; Amaral, C.M.; Peruzzo, D.C.; Duarte, P.M. Coronally Positioned Flap for Treatment of Restored Root Surfaces: A 6-Month Clinical Evaluation. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzadori, M.; Stefanini, M.; Sangiorgi, M.; Mounssif, I.; Monaco, C.; Zucchelli, G. Crown Lengthening and Restorative Procedures in the Esthetic Zone. Periodontol 2000 2018, 77, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchelli, G.; De Sanctis, M. Treatment of Multiple Recession-Type Defects in Patients With Esthetic Demands. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccuzzo, M.; Bunino, M.; Needleman, I.; Sanz, M. Periodontal Plastic Surgery for Treatment of Localized Gingival Recessions: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002, 29 (Suppl. S3), 178–194, discussion 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, T.W.; Robinson, M.; Gunsolley, J.C. Surgical Therapies for the Treatment of Gingival Recession. A Systematic Review. Ann. Periodontol. 2003, 8, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, F.; Pagliaro, U.; Nieri, M. Treatment of Gingival Recession with Coronally Advanced Flap Procedures: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellini, P.; Bissada, N.F. Mucogingival Conditions in the Natural Dentition: Narrative Review, Case Definitions, and Diagnostic Considerations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S190–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speroni, S.; Antonelli, L.; Coccoluto, L.; Giuffrè, M.; Sarnelli, F.; Tura, T.; Gherlone, E. The Effectiveness and Predictability of BioHPP (Biocompatible High-Performance Polymer) Superstructures in Toronto-Branemark Implant-Prosthetic Rehabilitations: A Case Report. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroca, S.; Keglevich, T.; Nikolidakis, D.; Gera, I.; Nagy, K.; Azzi, R.; Etienne, D. Treatment of Class III Multiple Gingival Recessions: A Randomized-Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculean, A.; Allen, E.P.; Katsaros, C.; Stähli, A.; Miron, R.J.; Deppe, H.; Cosgarea, R. The Combined Laterally Closed, Coronally Advanced Tunnel for the Treatment of Mandibular Multiple Adjacent Gingival Recessions: Surgical Technique and a Report of 11 Cases. Quintessence Int. 2021, 52, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculean, A.; Cosgarea, R.; Stähli, A.; Katsaros, C.; Arweiler, N.B.; Miron, R.J.; Deppe, H. Treatment of Multiple Adjacent Maxillary Miller Class I, II, and III Gingival Recessions with the Modified Coronally Advanced Tunnel, Enamel Matrix Derivative, and Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft: A Report of 12 Cases. Quintessence Int. 2016, 47, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietruska, M.; Skurska, A.; Podlewski, Ł.; Milewski, R.; Pietruski, J. Clinical Evaluation of Miller Class I and II Recessions Treatment with the Use of Modified Coronally Advanced Tunnel Technique with Either Collagen Matrix or Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft: A Randomized Clinical Study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambe, L.V.; Tandale, M.M.; Chhibber, R.; Wu, D.T. Treatment of Multiple Gingival Recessions Using Modified Tunnel Technique with V-Reverse Sutures: A Report of Three Cases. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2022, 23, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, M.P.; da Silva Feitosa, D.; Casati, M.Z.; Nociti, F.H.; Sallum, A.W.; Sallum, E.A. Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Evaluating Connective Tissue Graft plus Resin-Modified Glass Ionomer Restoration for the Treatment of Gingival Recession Associated with Non-Carious Cervical Lesion: 2-Year Follow-Up. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliberador, T.M.; Martins, T.M.; Furlaneto, F.A.C.C.; Klingenfuss, M.; Bosco, A.F. Use of the Connective Tissue Graft for the Coverage of Composite Resin-Restored Root Surfaces in Maxillary Central Incisors. Quintessence Int. 2012, 43, 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- Isler, S.C.; Ozcan, G.; Ozcan, M.; Omurlu, H. Clinical Evaluation of Combined Surgical/Restorative Treatment of Gingival Recession-Type Defects Using Different Restorative Materials: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Dent. Sci. 2017, 13, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, F.C.; Soeroso, Y.; Hutomo, D.I.; Harsas, N.A.; Sulijaya, B. Effectiveness of Restorative Materials on Combined Periodontal-Restorative Treatment of Gingival Recession with Cervical Lesion: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sanctis, M.; Di Domenico, G.L.; Bandel, A.; Pedercini, C.; Guglielmi, D. The Influence of Cementoenamel Restorations in the Treatment of Multiple Gingival Recession Defects Associated with Noncarious Cervical Lesions: A Prospective Study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2020, 40, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agossa, K.; Godel, G.; Dubar, M.; SY, K.; Behin, P.; Delcourt-Debruyne, E. Does Evidence Support a Combined Restorative Surgical Approach for the Treatment of Gingival Recessions Associated With Noncarious Cervical Lesions? J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2017, 17, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gingival Recession Defects | Periodontal Tissue Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KT | GT | IA | ||||||

| >2 mm | <2 mm | >1 mm | <1 mm | − | + | |||

| Dental surface defect evaluation | Class A (CEJ identifiable) | + (discrepancy) | Flaps + CTG | Flaps + CTG | Flaps + (depth discrepancy assessment) | Flaps + CTG | Flaps + CTG | Flaps + CTG |

| − (No discrepancy) | Flaps | Flaps + CTG | Flaps | Flaps + CTG | Flaps | Flaps + CTG | ||

| Class B (CEJ unidentifiable) | + (discrepancy) | Flaps + CTG + Enamel restoration | Flaps + CTG + Enamel restoration | Flaps + CTG + Enamel restoration | Flaps + CTG + Enamel restoration | Flaps + CTG + Enamel restoration | Flaps + CTG + Enamel restoration | |

| − (No discrepancy) | Flaps | Flaps + CTG | Flaps | Flaps + CTG | Flaps | Flaps + CTG | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coccoluto, L.; Speroni, S.; Rotundo, R. Clinical Management of Gingival Recessions with or Without Cervical Lesions: A Decisional Scheme Proposal. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176134

Coccoluto L, Speroni S, Rotundo R. Clinical Management of Gingival Recessions with or Without Cervical Lesions: A Decisional Scheme Proposal. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176134

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoccoluto, Luca, Stefano Speroni, and Roberto Rotundo. 2025. "Clinical Management of Gingival Recessions with or Without Cervical Lesions: A Decisional Scheme Proposal" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176134

APA StyleCoccoluto, L., Speroni, S., & Rotundo, R. (2025). Clinical Management of Gingival Recessions with or Without Cervical Lesions: A Decisional Scheme Proposal. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176134