Long-Term Follow-Up of a Patient with McCune–Albright Syndrome: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

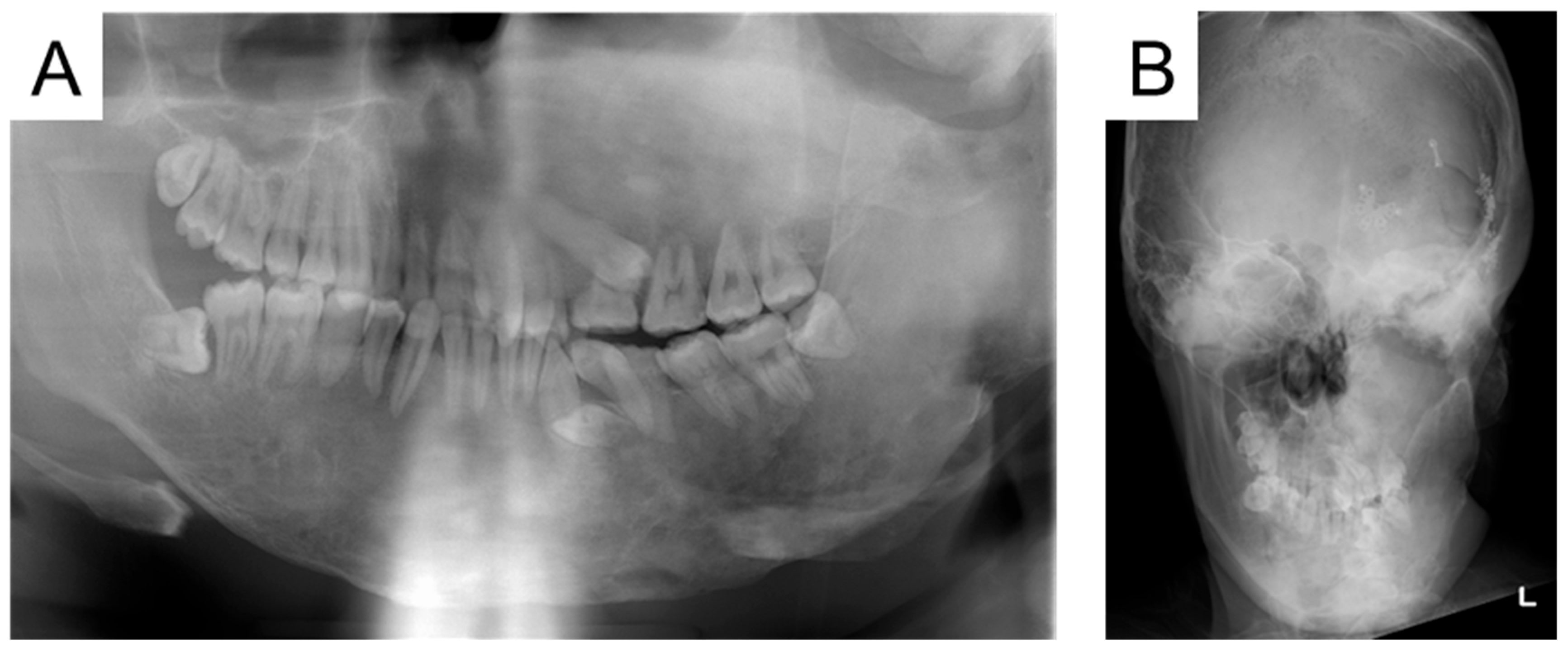

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Doan, N.; Duc, N.M.; Ngan, V.K.; Van Anh, N. McCune-Albright syndrome onset with vaginal bleeding. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e243401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, A.M.; Collins, M.T. Fibrous Dysplasia/McCune-Albright Syndrome: A Rare, Mosaic Disease of Gα s Activation. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, N.C.; Kontou, M.; Vasilakis, I.A.; Binou, M.; Lykopoulou, E.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C. McCune-Albright Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, C.E.; Collins, M.T. McCune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2008, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Feng, N.Y.; Lei, Y.J. Diagnosis and treatment of McCune-Albright syndrome: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 6817–6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A.B.; Collins, M.T.; Boyce, A.M. Fibrous dysplasia of bone: Craniofacial and dental implications. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczuk, V.; Florenzano, P.; de Castro, L.F.; Collins, M.T.; Boyce, A.M. Fibrous Dysplasia/McCune-Albright Syndrome. In GeneReviews® [Internet]; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Akintoye, S.O.; Boyce, A.M.; Collins, M.T. Dental perspectives in fibrous dysplasia and McCune-Albright syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 116, e149–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, W.E.; Ross, A.T. McCune-Albright syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2002, 65, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamadani, M.; Chaudhary, L. McCune-Albright syndrome. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, R.; Cherian, K.E.; Asha, H.S.; Paul, T.V. McCune Albright syndrome: An endocrine medley. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e229141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Hasebe, D.; Kano, H.; Saito, C. A Study in Subjective Evaluation and Gaze Point Analysis of Facial Symmetry: Analysis Using Eye-tracking. Jpn. J. Jaw Deform. 2009, 19, 184–192. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akitomo, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kametani, M.; Kaneki, A.; Nishimura, T.; Mitsuhata, C.; Nomura, R. Eruption Disturbance in Children Receiving Bisphosphonates: Two Case Reports. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravinda, K.; Ratnakar, P.; Srinivas, K. Oral manifestations of McCune-Albright syndrome. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, X.; Guo, Q. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ): A review of pathogenesis hypothesis and therapy strategies. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soutome, S.; Hayashida, S.; Funahara, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kojima, Y.; Yanamoto, S.; Umeda, M. Factors affecting development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients receiving high-dose bisphosphonate or denosumab therapy: Is tooth extraction a risk factor? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsuhata, C.; Kozai, K. Management of bisphosphonate preparation-treated children in the field of pediatric dentistry. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2022, 58, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, N.T.; Rech, B.O.; Martins, I.G.; Franco, J.B.; Ortega, K.L. Can children be affected by bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw? A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, N.; Wu, Y. Age-Related Changes in Facial Soft Tissue of Han Chinese: A Computed Tomographic Study. Dermatol. Surg. 2022, 48, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichard, D.C.; Boyce, A.M.; Collins, M.T.; Cowen, E.W. Oral pigmentation in McCune-Albright syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2014, 150, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akintoye, S.O.; Lee, J.S.; Feimster, T.; Booher, S.; Brahim, J.; Kingman, A.; Riminucci, M.; Robey, P.G.; Collins, M.T. Dental characteristics of fibrous dysplasia and McCune-Albright syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2003, 96, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

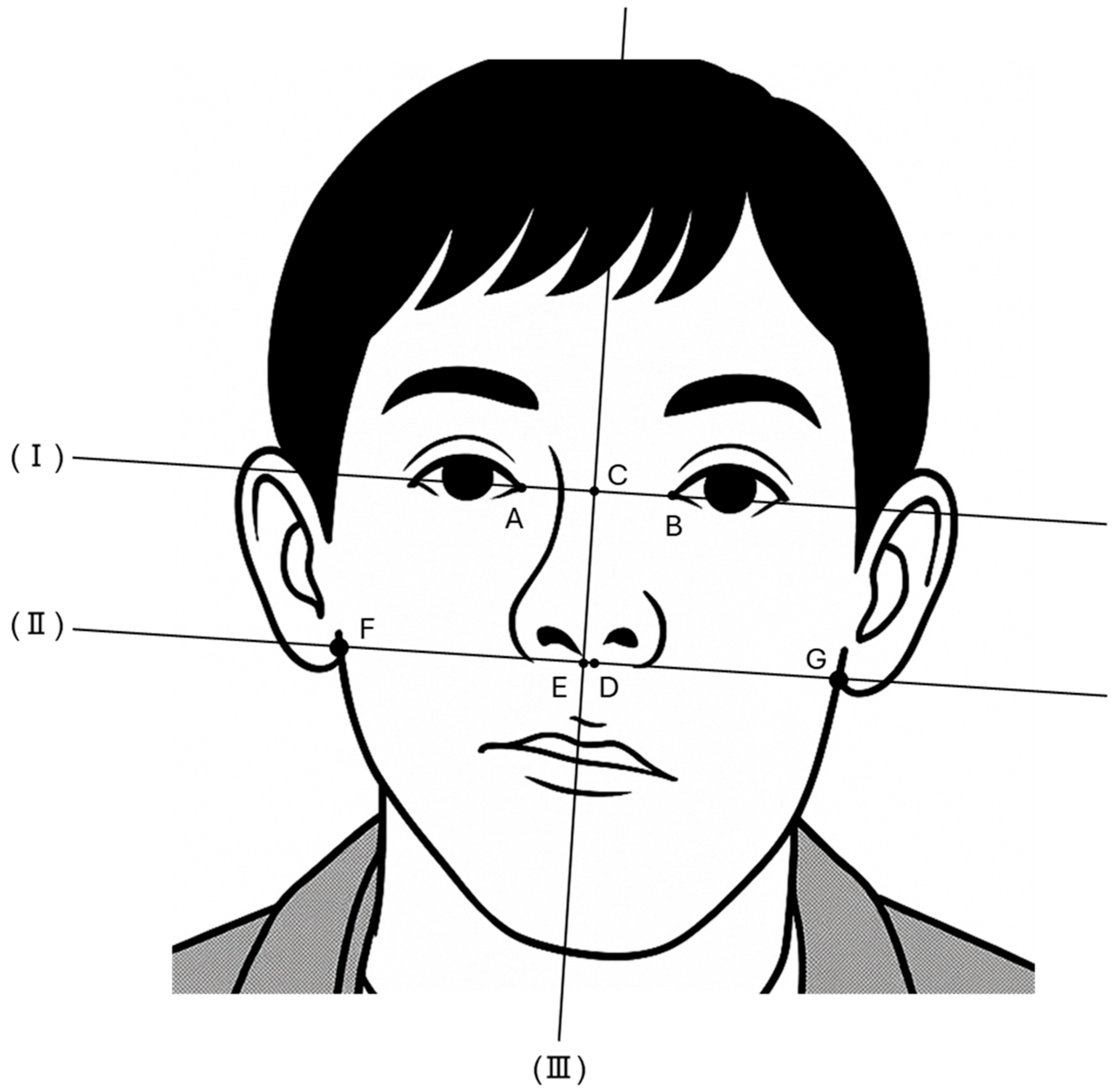

| Point | |

|---|---|

| A | Right endocanthion |

| B | Left endocanthion |

| C | Midpoint of bilateral endocanthion |

| D | Subnasale |

| E | Intersection of lines (II) and (III) |

| F | Intersection of line (II) and the right side of the face |

| G | Intersection of line (II) and the left side of the face |

| Line | |

| (I) | Line joining bilateral inner canthi |

| (II) | Line parallel to line (I) that passes through D |

| (III) | Line perpendicular to line (I) that passes through C |

| Ratio | Formula (%) |

|---|---|

| Asymmetry ratio from midline | |(EF − EG)/(EF + EG)| × 100 |

| Asymmetry ratio from subnasale | |(DF − DG)/(DF + DG)| × 100 |

| Age | Asymmetry Ratio from Midline (%) | Asymmetry Ratio from Subnasale (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 14 y 9 m | 0.94 | 4.46 |

| 17 y 3 m | 7.19 | 12.66 |

| 19 y 9 m (Before osteotomy) | 15.36 | 25.89 |

| 19 y 10 m (After osteotomy) | 0.78 | 9.54 |

| 20 y 9 m | 1.88 | 6.82 |

| 21 y 9 m | 1.01 | 2.61 |

| 23 y 3 m | 2.11 | 7.91 |

| 25 y 1 m | 9.11 | 20.85 |

| 27 y 4 m | 6.85 | 18.38 |

| 30 y 5 m | 4.86 | 14.38 |

| Age | Occurrences |

|---|---|

| 5 y | Swelling in the left cheek region |

| 9 y | Diagnosis of MAS and precocious puberty, and start of bisphosphonate therapy |

| 11 y | Optic canal decompression surgery |

| 13 y 7 m | First visit to our department |

| 15 y 6 m | Left maxillary primary first molar extraction |

| 19 y 5 m | Discontinuation of bisphosphonate therapy |

| 19 y 9 m | Maxillary and mandibular osteotomies |

| 24 y 10 m | Left mandibular primary second molar extraction |

| 30 y 3 m | Left mandibular primary canine extraction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shoji, Y.; Kusaka, S.; Kawashima, K.; Hamaguchi, S.; Tachikake, M.; Akitomo, T.; Nomura, R. Long-Term Follow-Up of a Patient with McCune–Albright Syndrome: A Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176101

Shoji Y, Kusaka S, Kawashima K, Hamaguchi S, Tachikake M, Akitomo T, Nomura R. Long-Term Follow-Up of a Patient with McCune–Albright Syndrome: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176101

Chicago/Turabian StyleShoji, Yuto, Satoru Kusaka, Kana Kawashima, Shuma Hamaguchi, Meiko Tachikake, Tatsuya Akitomo, and Ryota Nomura. 2025. "Long-Term Follow-Up of a Patient with McCune–Albright Syndrome: A Case Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176101

APA StyleShoji, Y., Kusaka, S., Kawashima, K., Hamaguchi, S., Tachikake, M., Akitomo, T., & Nomura, R. (2025). Long-Term Follow-Up of a Patient with McCune–Albright Syndrome: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176101