Reconstruction After Wide Excision of the Nail Apparatus in the Treatment of Melanoma: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

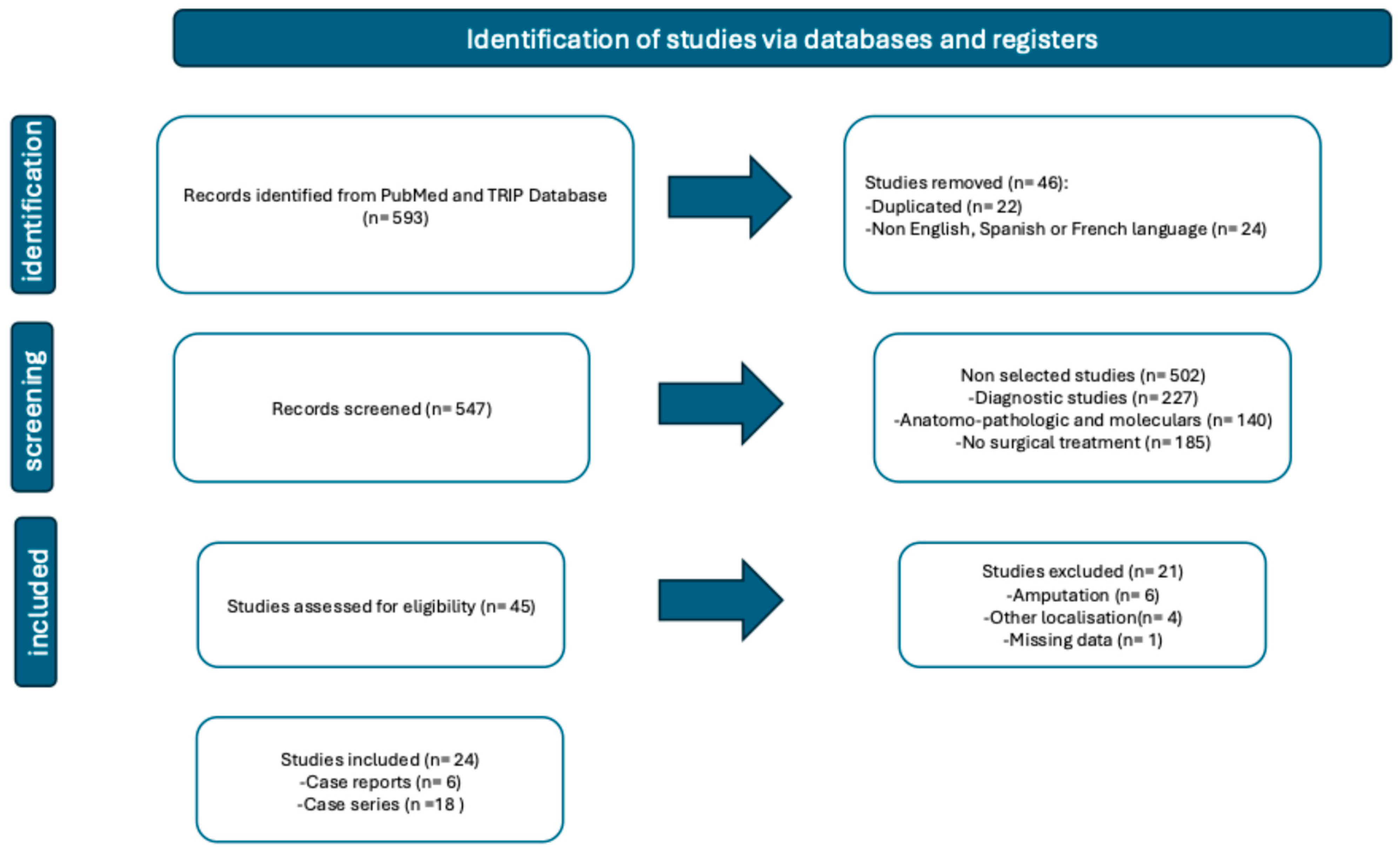

2. Materials and Methods

- Literature search

- Study Selection

- -

- Type of study: case series, case reports, cohort studies, and randomized controlled trials of nail reconstruction after melanoma removal.

- -

- Participants: adult or pediatric patients undergoing reconstruction after removal of a subungual melanoma of the upper or lower limb.

- -

- Results reported: type of melanoma and excision (margins), reconstruction technique, time frame, adjuvant treatments, complications, functional and aesthetic results, patient satisfaction, recurrences, and length of follow-up.

- Data Collection

- Data synthesis and analysis

3. Results

- Study selection

- Study characteristics

- Demographic characteristics

- Anatomical localization

- Melanoma type

- Margins

- Strategy for reconstruction

- Carcinologic complications

- ○

- ○

- ○

- Non-carcinologic post-operative complications

- Complementary treatments

- Functional and cosmetic results

- Post-operative follow-up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SUM | Subungual melanoma |

| WLE | Wide local excision (of nail apparatus) |

| F | Finger |

| T | Toe |

| FTSG | Full-thickness skin graft |

| STSG | Split-thickness skin graft |

| NA | Non available |

| Quick DASH | Score Quick Disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand (score ranges from 0, no obstacles, to 100, maximum obstacles) |

| MMWS | score ranging from 0, maximum disability, to 100, no disability |

| Score AOFAS | The American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Score (score ranging from 0, maximum disability, to 90, no disability) |

| FS | Functional surgery |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute checklist |

| FFI | Foot Function Index |

| PROMs | Patient-reported outcome measures |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

References

- Sun, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Jia, L.; Chai, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wu, M.; Li, Y. Global trends in melanoma burden: A comprehensive analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 1990–2021. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025, 92, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, A. Tumor thickness in evaluating prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann. Surg. 1978, 187, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, A. Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann. Surg. 1970, 172, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Yoon, J.; Chung, Y.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, J.Y.; Shin, O.R.; Park, H.Y.; Bahk, W.J.; Yu, D.S.; Lee, Y.B. Whole-exome sequencing reveals differences between nail apparatus melanoma and acral melanoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 559–561.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feibleman, C.E.; Stoll, H.; Maize, J.C. Melanomas of the palm, sole, and nailbed: A clinicopathologic study. Cancer 1980, 46, 2492–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodland, D.G. The treatment of nail apparatus melanoma with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol. Surg. 2001, 27, 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Haneke, E. Ungual melanoma—controversies in diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol. Ther. 2012, 25, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Ohara, K.; Kishi, A.; Teramoto, Y.; Sato, S.; Fujisawa, Y.; Fujimoto, M.; Otsuka, F.; Hayashi, N.; Yamazaki, N.; et al. Effects of non-amputative wide local excision on the local control and prognosis of in situ and invasive subungual melanoma. J. Dermatol. 2015, 42, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, A.M.; Buchanan, P.J.; Bueno, R.A.; Jr Neumeister, M.W. Subungual melanoma: A review of current treatment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 134, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple-Oberle, C.; Nicholas, C.; Rojas-Garcia, P. Current Controversies in Melanoma Treatment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 151, 495e–505e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, R.G.-B.S.M.I.; Robert, C. Traitement du mélanome de l’appareil unguéal. Ann. Dermatol. Vénéréologie 2021, 1, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovgaard, C.; Angermann, P.; Hovgaard, D. The social and economic consequences of finger amputations. Acta. Orthop. Scand. 1994, 65, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poumellec, M.A.; Camuzard, O.; Dumontier, C. Hook nail deformity. Hand. Surg. Rehabil. 2024, 43s, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda-Juárez, M.C.; Martínez-Velasco, M.A.; Fonte-Ávalos, V.; Toussaint-Caire, S.; Domínguez-Cherit, J. Conservative surgical management of in situ subungual melanoma: Long-term follow-up. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, A.; Abimelec, P.; Dumontier, C. Full thickness skin graft for nail unit reconstruction. J. Hand. Surg. Br. 2005, 30, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhaindran, M.E.; Cordeiro, P.G.; Disa, J.J.; Mehrara, B.J.; Athanasian, E.A. Full-thickness skin graft after nail complex resection for malignant tumors. Tech. Hand. Up. Extrem. Surg. 2011, 15, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Terry, M.; Romero-Aguilera, G.; Mendoza, C.; Franco, M.; Cortina, P.; Garcia-Arpa, M.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, L.; Garrido, J.A. Functional Surgery for Malignant Subungual Tumors: A Case Series and Literature Review. Actas Dermosifiliogr. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 109, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehrle, M.; Metzger, S.; Schippert, W.; Garbe, C.; Rassner, G.; Breuninger, H. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol. Surg. 2003, 29, 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Goettmann, S.; Moulonguet, I.; Zaraa, I. In situ nail unit melanoma: Epidemiological and clinic-pathologic features with conservative treatment and long-term follow-up. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 2300–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinno, S.; Wilson, S.; Billig, J.; Shapiro, R.; Choi, M. Primary melanoma of the hand: An algorithmic approach to surgical management. J. Plast. Surg. Hand. Surg. 2015, 49, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.H.; Lee, S.; Park, J.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Roh, M.R.; Nam, K.A.; Chung, K.Y. Risk of recurrence of nail unit melanoma after functional surgery versus amputation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollina, U.; Tempel, S.; Hansel, G. Subungual melanoma: A single center series from Dresden. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Park, B.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, K.T.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, D.Y.; Mun, G.H. Superthin SCIP Flap for Reconstruction of Subungual Melanoma: Aesthetic Functional Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 1278–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureda, N.; Phan, A.; Poulalhon, N.; Balme, B.; Dalle, S.; Thomas, L. Conservative surgical management of subungual (matrix derived) melanoma: Report of seven cases and literature review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neczyporenko, F.; André, J.; Torosian, K.; Theunis, A.; Richert, B. Management of in situ melanoma of the nail apparatus with functional surgery: Report of 11 cases and review of the literature. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terushkin, V.; Brodland, D.G.; Sharon, D.J.; Zitelli, J.A. Digit-Sparing Mohs Surgery for Melanoma. Dermatol. Surg. 2016, 42, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayatt, S.S.; Dancey, A.L.; Davison, P.M. Thumb subungual melanoma: Is amputation necessary? J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2007, 60, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imakado, S.; Sato, H.; Hamada, K. Two cases of subungual melanoma in situ. J. Dermatol. 2008, 35, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.H.; Hsieh, M.C.; Chou, P.R.; Huang, S.H. Reconstruction for Defects of Total Nail Bed and Germinal Matrix Loss with Acellular Dermal Matrix Coverage and Subsequently Skin Graft. Medicina 2020, 56, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, D.; Gülke, J.; Janetzko, C.; Kastler, S.; Treiber, N.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K.; Schneider, L.A. Digit preserving surgery of subungual melanoma: A case series using vacuum assisted closure and full-thickness skin grafting. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, e537–e538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, W.A.; Quirey, R.A.; Guillén, D.R.; Munõz, G.; Taylor, R.S. Presentation, histopathologic findings, and clinical outcomes in 7 cases of melanoma in situ of the nail unit. Arch. Dermatol. 2004, 140, 1102–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.T.; Bhat, W.; Magdub, S.; Orlando, A. In situ subungual melanoma: Digit salvaging clearance. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2013, 66, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.F.; Correia, O.; Barros, A.M.; Azevedo, R.; Haneke, E. Nail matrix melanoma in situ: Conservative surgical management. Dermatology 2010, 220, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smock, E.D.; Barabas, A.G.; Geh, J.L. Reconstruction of a thumb defect with Integra following wide local excision of a subungual melanoma. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2010, 63, e36–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, S.; Ježić, I.; Bulić, K. Reconstruction of a Thumb Defect Following Subungual Melanoma Resection Using Foucher’s Flap. Acta. Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2019, 27, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, A.; López, C.; Acosta, A.; Peñaranda, C. Subungual melanoma in situ in a Hispanic girl treated with functional resection and reconstruction with onychocutaneous toe free flap. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143, 1600–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Uhara, H.; Koga, H.; Okuyama, R.; Saida, T. Surgical treatment of nail apparatus melanoma in situ: The use of artificial dermis in reconstruction. Dermatol. Surg. 2012, 38, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, A. A fungus hematode du petit doigt. Gaz. Med. 1834, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Levit, E.K.; Kagen, M.H.; Scher, R.K.; Grossman, M.; Altman, E. The ABC rule for clinical detection of subungual melanoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 42 Pt 1, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.T.; Wright, N.A.; Cockerell, C.J. Biopsy of the pigmented lesion—When and how. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008, 59, 852–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, B.; Dalac, S.; Denis, M.G.; Dupuy, A.; Emile, J.F.; De La Fouchardiere, A.; Hindie, E.; Jouary, T.; Lassau, N.; Mirabel, X. French updated recommendations in Stage I to III melanoma treatment and management. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.G.; Blessing, K.; Kernohan, N.M. Surgical aspects of subungual malignant melanomas. The Scottish Melanoma Group. Ann. Surg. 1992, 216, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, G.; Cho, S.I.; Choi, S.; Mun, J.H. Functional surgery versus amputation for in situ or minimally invasive nail melanoma: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimyai-Asadi, A.; Katz, T.; Goldberg, L.H.; Ayala, G.B.; Wang, S.Q.; Vujevich, J.J.; Jih, M.H. Margin involvement after the excision of melanoma in situ: The need for complete en face examination of the surgical margins. Dermatol. Surg. 2007, 33, 1434–1439; discussion 9–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, B.B.; Bradley, E.; Berger, A.C. Margins of Melanoma Excision and Modifications to Standards. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 29, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetter, S.M.; Tsao, H.; Bichakjian, C.K.; Curiel-Lewandrowski, C.; Elder, D.E.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Guild, V.; Grant-Kels, J.M.; Halpern, A.C.; Johnson, T.M.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 208–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A.; Paleu, G.; Guena, B.; Chaput, B.; Camuzard, O.; Lupon, E. Posterior arm perforator flap for coverage of the scapular area. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2025, 70, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meresse, T.; Lupon, E.; Berkane, Y.; Classe, J.M.; Camuzard, O.; Gangloff, D. Oncologic plastic surgery: An essential activity to develop in France. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2023, 68, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadia, R.; Rousset, P.; Massalou, D.; Camuzard, O.; Montaudié, H.; Lupon, E. Management of a large abdominal dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans requiring a life-threatening excision: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case. Rep. 2025, 133, 111579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboye, M.; Majchrzak, A.; d’Andréa, G.; Bronsard, N.; Camuzard, O.; Lupon, E. The First Dorsal Metatarsal Artery Perforator Flap: A Description and Anatomical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, C.U.; Lucas, M.W.; Scolyer, R.A.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Menzies, A.M.; Lopez-Yurda, M.; Hoeijmakers, L.L.; Saw, R.P.; Lijnsvelt, J.M.; Maher, N.G.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Resectable Stage III Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouquet, L.; Poissonnet, G.; Picard, A.; Camuzard, O.; Gangloff, D.; Lupon, E. What’s new in oncologic plastic surgery in 2025? Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2025, 5, S0294–S1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Type of Article Number of Patients Distribution Mean Age (Years) (Range) | Localization F (Finger) T (Toe) (n) | Local Extension | Presence of Previous Biopsy Margins from Nail Apparatus | Strategy of Reconstruction Surgical Management | Side Effects, Complications | Complementary Treatment | Results | Follow Up Mean (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anda-Juarez et al., An Bras Dermatol, 2016 [15] | Retrospective 15 patients (9F, 6M) 31 (4–66) | Right hand: F2 (2), F4 (2), F5 (1) Left hand: F1 (1), F5 (3) Right foot (5): T1 (5) Left foot (1): T1 | SUM in situ | 5 mm Supra periosteum resection | FTSG (14) Banner flap (1 patient) | No recurrence Inclusion cysts (4) Spicules (6) Hypersensitivity (4) Moderate chronic pain (1) Hyperpigmentation of the skin graft (9) | NA | Functional and cosmetic outcomes were good in all of them | 55 months (12–98) |

| Lazar et al., HandSurg Br, 2005 [16] | Retrospective 13 patients (8F, 5M) 10 patients with SUM (7F, 3M) 40 (NA) | Right hand F1 (3), F3 (1), F5 (1) Left hand: F1 (2), F5(3) | SUM in situ | 5 mm | Immediate FTSG harvested from same forearm (9) Delayed FTSG harvested from same forearm (1) | Temporary finger exclusion (1 case) Epidermal cyst (5 cases) | NA | Sensitivity: Weber 4–6 mm (7), NA (1) Normal function (4), Slightly limited function (5), NA (1) Cosmetic outcome: Satisfied or normal (9), NA (1) | 48 months (6–84) |

| Puhaindran et al., Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg, 2011 [17] | Retrospective 10 patients (4F, 6 M) 6 patients with a SUM MA 52 (24–80) | NA | SUM in situ, <2 cm diameter | 2 mm to nail fold | Immediate FTSG | Positive margin (1), treated by PID Disarticulation Secondary surgery: Epidermal inclusion cyst (1) Nail remnant (1) | NA | Acceptable appearance for all patients (assessed by 2 surgeons) Patients satisfied (6) Unrestricted use of the hand (6) | 35 months (8–72) |

| Flores-Terry et al., Actas Dermosifiliogr, 2018 [18] | Retrospective 11 patients 7 patients with SUM (4F, 3M) 5 patients (3F, 2M) treated by WLE 61 (45–81) | Right hand: F2 (1) F3 (1) Left hand F1 (1) F2 (1) Right foot: T1 (1) | SUM in situ (4) or Sum with Breslow < 1 mm (1) | Previous biopsy 5 mm Supra periosteum resection | Circumferential advancement flap and Immediate FTSG | No recurrency (5) Wound infection (2) subungual spicules (1), moderate stiffness of DIP of one finger (1), hypersensitivity to cold (2), hypersensitivity to mild trauma (4) | NA | Patients were satisfied with the procedure and the results obtained (5) Satisfaction was good, and the impact on quality of life was minimal (5) | 39 months (12–96) |

| Moehrle et al., Dermatol Surg, 2003 [19] | Retrospective 62 patients with SUM (25H, 37F) 31 treated by WLE (11H, 20F) MA 61 | F1,2,3,4,5 (20) T1,2,3,4,5 (11) | SUM in situ Invasive SUM Breslow < 1 mm (6) Breslow 1 to 2 mm (8) Breslow 2 to 4 mm (6) Breslow > 4 mm (4) NA: (7) | 5 mm WLE with safety margin without bone resection (3) WLE with safety margin with resection of the distal part of the distal phalanx (28) | FTSG with pulpal advancement flap Single stage (1) Several stages (30) Unspecified reconstruction after definitive three-dimensional histology | Recurrences (20 patients) Local recurrence (2) In transit recurrence (1) Lymph node metastasis (7) Distant metastasis (1) | NA | Function and cosmesis of the involved finger or toe “preserved” | 54 months (NA) |

| Goettmann et al., J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2018 [20] | Retrospective 63 patients (44F, 19M) 58 treated by WLE 51 (NA) | F1 (24) F2,3,4,5 (23) T1 (10) T3 (1) | All SUM, if pulp is not involved | No previous biopsy WLE (12) Partial excision of the appliance, removal of the lesion, and the nearby paronychium (47) | Healing by secondary intention (52) FTSG (3 patients) Flap (1) | Local recurrences at 24 and 32 months treated by amputation (2) Spicules (7) Epidermal cysts (2) | NA | No functional discomfort (20) Moderate discomfort (14) Aesthetic discomfort was judged to be absent (29) Moderate aesthetic discomfort (8) Severe aesthetic discomfort (2) | 120 months (NA) |

| Chow et al., J Plast Reconstru Surg, 2013 [33] | Case report 1M with SUM in situ 41 | Right T1 (1) | SUM in situ | Biopsy 10 mm WLE with a layer of bone | Immediate FTSG (harvested from the groin) | NA | NA | Acceptable cosmetic result (assessed by surgeon) | 5 months |

| Duarte et al., Dermatol, 2010 [34] | Case report 1F with SUM in situ 61 | Right F1 (1) | SUM in situ | Excisional biopsy 3 weeks later 3 mm margin WLE | FTSG taken from the arm | No local recurrence or metastasis | NA | Thumb function completely preserved | 12 months |

| High et al., Arch Dermatol, 2004 [32] | Retrospective 7 patients (5F, 2M) with SUM in situ 4 patients treated by WLE MA 56 (NA) | Right hand (1): F2 Left hand (2): F2 (1), F5 (1) Right foot (1): T1 (1) | SUM in situ | Previous biopsy MOHS surgery: 1 stage (3) 2 stages (1) | FTSG taken from the arm (3) cross finger flap (1) | Recurrence: (1) treated by revisional amputation | NA | NA | 24 months (10–29) |

| Sinno et al., J Plast Surg Hand Surg, 2015 [21] | Retrospective 35 patients with melanoma of the hand (24F, 11M) 18 patients with SUM 10 patients with SUM treated by WLE | F1 (8) F2 (12) F3 (3) F5 (3) | Melanomas in situ (7) Invasive Melanoma T2 (1 patients) B = 2.5 mm Invasive Melanoma T3 (2); B = 3.00 mm and B = 3.08 mm | 5 mm | FTSG (3) Paronychial advancement flap + FTSG (3) Paronychial advancement flap + forearm flap + FTSG (1) Paronychial advancement flap + FTSG Volar Flap FTSG (1) FTSG Volar and dorsal advancement flaps (1) FTSG Local advancement flap (1) | Revisional amputation (3) Unknown (1) Deceased (1) | NA | NA | 47 months (7–74) |

| Smock et al., J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 2010 [35] | Case report 1M 44 | Right F1 (1) | Ulcerated SUM Breslow of 1.2 mm | Previous Biopsy 10 mm, including the periosteum | Immediate reconstruction by dermal matrix (INTEGRA) STSG 3 weeks later | None | NA | Fully functional thumb and a good cosmetic result Went back to job at 4 weeks | 24 months |

| Bjedov et al., Acta Dermato Venereol Croat, 2019 [36] | Case report (1) F, 31 | Left F1 (1) | SUM in situ | Several nail matrix biopsies 5 mm, with periosteum Mohs analysis | Pedicled innervated Fascio-cutaneous Foucher’s flap The donor site was covered with an FTSG taken from the volar side of the elbow. | None | NA | The hand was fully functional, and the patient was very satisfied with the appearance of the thumb Full sensory cortical reorientation | 3 months |

| Oh et al., J Am Acad Dermatol, 2023 [22] | Retrospective 140 patients with SUM 107 with conservative treatment (57F, 50H) Mean age: 56 | F1,2,3,4,5 (71) T1,2,3,4,5 (36) | If no bone invasion (MRI + biopsy) | Biopsy and MRI at least 3 to 4 mm, with periosteum | NA | Recurrence (23 patients): Local recurrence (15) Distant recurrences (8) | NA | NA | 45 months (14–76) |

| Motta et al., Arch Dermatol, 2007 [37] | Case report 12 years old, F | Right F1 (1) | SUM in situ | Biopsy WLE with Mohs Micrographic analysis 5–10 mm (lateral) 5 mm (proximal and distal edges) | Two stages Second stage (1 week later) microvascular composite onychocutaneous free flap from the right first toe | NA | NA | Normal nail growth and full mobility of the interphalangeal thumb joint were present | 3 months |

| Wollina et al., Dermatol Ther, 2019 [23] | Retrospective Series of 12 patients with SUM) 6 patients with conservative treatment (2F, 4M) 76 (NA) | Right foot T1 (2) T3 (1) Left foot: T1 (3) | SUM with Breslow between 1.6 mm and 4.8 mm | Wide excision (4) Excision with delayed Mohs surgery (2) | Full-thickness skin transplantation. One patient refused, second intention healing | Local relapse (2) Later metastasis (1) Satellites only (1 patient, B = 2.55) Liver, pancreas, spleen, lymph nodes, stomach, adrenal glands, greater omentum, CNS (1, with Breslow = 4.8 mm) In transit, lymph node regional, pericardium (1, with Breslow = 3.20) | Sentinel Lymph node (4), with micro-invasion (1) Polychemotherapy for later metastasis (1) Transit metastases treated by erbium YAG-laser as a palliative measure (1) interferon-alfa therapy for 9 years after surgery, satellite metastasis (1) Adjuvant radiotherapy (1) | NA | 104 months (17–208) |

| Crisan et al., Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2017 [31] | Retrospective Series of 7 patients (3F, 4H) 64 (NA) | F1 (3) F4 (3) T1 (1) | SUM in situ pT1a (1) pT1b (1) | WLE (7) NA | First stage: vacuum-assisted closure Second stage: FTSG (5) | Second stage amputation (2 patients) for: -DIP joint arthritis (1) -Positive margin (1) | NA | At 6 weeks, the 5 patients grafted could resume normal activity Good cosmetic and functional | 12 months (NA) |

| Lee et al., Plast Reconstr Surg, 2017 [24] | Prospective 41 patients with conservative treatment (21M, 20F) 51.1 (NA) | Fingers: 25 Toes: 16 | SUM with Breslow thickness of ≤2 mm on preoperative biopsy | Preoperative biopsy 5 mm with periosteum excised (10 mm margin if invasive lesion) | Immediate reconstruction by SCIP flap with a final thickness ranging from 1.5 to 4 mm after defatting (Scouted with Doppler) End-to-end anastomosis with digital artery and dorsal vein Donor site primary closing | Necrosis of the flap (1) (arterial insufficiency) Venous congestion (3) with partial necrosis of the flap Seroma of the donor site (1). Recurrences: -local recurrence (1) -metastasis in transit (1) Second surgical stage until degreasing (12) | NA | Average healing time: 15 days Questionnaire carried out on 26 patients: WLE in the upper limb (14): The mean Quick-DASH score was 1.3 (range 0 to 6.8). WLE in the lower limb (12): FFI survey for foot lesions. mean score was 3.1 (range 0 to 8.0) | 31 months (NA) |

| Hayashi et al., Dermatol Surg, 2012 [38] | Case report (1M), 52 | Left F3 | SUM in situ | No biopsy 5 mm with excision of periosteum | Immediate reconstruction with artificial dermis (PELNAC) Second stage at 4 weeks with FTSG | No recurrency No metastasis | NA | Good cosmetic results | 3 months |

| Sureda et al., Br J Dermatol, 2011 [25] | Retrospective Series of 7 patients (5F, 2M) MA 58 y | F1 (2), F2 (2), F4 (1) T1 (2) | SUM in situ (5) or minimally invasive SUM (2) (Breslow 0.2 and 0.15) | Biopsy systematically 5–10 mm Deep margin was bone contact | Immediate FTSG taken from the internal aspect of an arm | No recurrence | NA | Interrogation of patient and observer: High level of satisfaction, a good functional and quite good cosmetic result. | 45 months (24–84) |

| Neczyporenko et al., J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2014 [26] | Retrospective Series of 11 patients (8F, 3M) 48 (NA) | Right hand: F1 (3), F2 (1), F5 (1) Left hand: F1 (1) F2 (1) T1 (3), T2 (1) | Melanoma in situ | Biopsy systematically (tangential or punch) 6 mm | Immediate FTSG (6) Secondary intention and delayed FTSG (5) | Tendon sheath hematoma (1) Lymphangitis post (1) Recurrence treated by secondary amputation and sentinel node (2) (7- and 11 years post op) | NA | Healing by secondary intention and grafting were fully satisfactory, cosmetically and functionally | 65 months (5–167) |

| Terushkin et al., Dermatol Surg, 2016 [27] | Retrospective Series of 40 patients (21F, 19M) 63 (NA) | NA | WLE in cases of extensive SUM (>40% of the bed) | Excisional biopsy with Mohs micrograph, Supra Periosteum dissection | Second intention FTSG STSG | Recurrences (5) Second operation with complete excision of the matrix (2) Amputation (2) Death due to metastasis (1) | NA | NA | 76 months (2–276) |

| Rayatt et al., Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 2007 [28] | Retrospective Series of 4 patients 56 (NA) | F1 (4) | SUM without deep margin clinically involved Breslow 0.9 mm to 4 mm | All had initial biopsies to confirm the diagnosis 10 mm including the periosteum | Immediate: -Foucher flap (1) -Flag flap (2) Delayed reconstruction (flag flap) (1) | Recurrence at 36 months treated by amputation (1) | NA | Usefully maintain function. | 72 months (−117) |

| Imakado et al., J Dermatol, 2008 [29] | Retrospective Series of 2 patients (1M, 1F) 50 | Left F3 (1) Right F5 (1) | SUM in situ | All the nail apparatus with nail folds | Immediate FTSG | No recurrence | NA | NA | 27 months (6–48) |

| Liu et al., Medicina, 2020 [30] | Retrospective Series of 4 patients with malignant tumor of nail apparatus 3 patients with SUM suspicion (1F, 2M) MA 55 y | Left T1 (1) Right T1 (2) | SUM in situ (2) hyperpigmentation in basal layer of epidermis (1) | Previous biopsy (2) WLE Adequate margin control confirmed by intraoperative frozen sections | Two-stage reconstruction Immediate acellular dermal matrix (PELNAC) At 10 days, the acellular dermal matrix was removed and re-dressed with a new one at the outpatient clinic FTSG at 3 weeks | No Recurrence | NA | These patients experienced minimal change in body contour, mild but acceptable functional deficit, and satisfying aesthetic results. | 9 months (5–13) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chouquet, L.; Boukari, F.; Balaguer, T.; Montaudié, H.; Camuzard, O.; Lupon, E. Reconstruction After Wide Excision of the Nail Apparatus in the Treatment of Melanoma: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175932

Chouquet L, Boukari F, Balaguer T, Montaudié H, Camuzard O, Lupon E. Reconstruction After Wide Excision of the Nail Apparatus in the Treatment of Melanoma: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):5932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175932

Chicago/Turabian StyleChouquet, Luc, Feriel Boukari, Thierry Balaguer, Henri Montaudié, Olivier Camuzard, and Elise Lupon. 2025. "Reconstruction After Wide Excision of the Nail Apparatus in the Treatment of Melanoma: A Systematic Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 5932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175932

APA StyleChouquet, L., Boukari, F., Balaguer, T., Montaudié, H., Camuzard, O., & Lupon, E. (2025). Reconstruction After Wide Excision of the Nail Apparatus in the Treatment of Melanoma: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 5932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175932