Ethnic Differences in Dementia Diagnosis and Treatment in Israel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Health Conditions and Risk Factors

3.3. Diagnosis and Initial Work-Up

3.4. Treatment and Follow-Up Care

Multivariable Analysis of Ethnicity and Dementia Subtype

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsoy, E.; Kiekhofer, R.E.; Guterman, E.L.; Tee, B.L.; Windon, C.C.; Dorsman, K.A.; Lanata, S.C.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Miller, B.L.; Kind, A.J.H.; et al. Assessment of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Timeliness and Comprehensiveness of Dementia Diagnosis in California. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, N.; Barnes, D.E.; Habib, M.; Nianogo, R.A. Forecasting the 20-year incidence of dementia by socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and region based on mid-life risk factors in a U.S. nationally representative sample. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 99, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specktor, P.; Ben Hayun, R.; Yarovinsky, N.; Fisher, T.; Aharon Peretz, J. Ethnic Differences in Attending a Tertiary Dementia Clinic in Israel. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 578068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, H.; Mukaetova-ladinska, E.B.; Wilson, A.; Bankart, J. Representation of Black, Asian and minority ethnic patients in secondary care mental health services: Analysis of 7-year access to memory services in Leicester and Leicestershire. BJPsych Bull. 2020, 44, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.L.; Jimenez, D.E.; Cucciare, M.A.; Tong, H.Q.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. Ethnic Differences in Beliefs Regarding Alzheimer Disease Among Dementia Family Caregivers. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livney, M.G.; Clark, C.M.; Karlawish, J.H.; Cartmell, S.; Negrón, M.; Nuñez, J.; Xie, S.X.; Entenza-Cabrera, F.; Vega, I.E.; Arnold, S.E. Ethnoracial Differences in the Clinical Characteristics of Alzheimer’s Disease at Initial Presentation at an Urban Alzheimer’s Disease Center. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, P.; Friedland, R.P.; Inzelberg, R. Alzheimer’s Disease and the Elderly in Israel: Are We Paying Enough Attention to the Topic in the Arab Population? Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2015, 30, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, J.C.; Aita, S.L.; Bene, V.A.D.; Rhoads, T.; Resch, Z.J.; Eloi, J.M.; Walker, K.A. Black and White individuals differ in dementia prevalence, risk factors, and symptomatic presentation. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Freha, N.; Alamour, O.; Weissmann, S.; Esbit, S.; Cohen, B.; Gordon, M.; Abu-Freha, O.; El-Saied, S.; Afawi, Z. Ethnic Disparities in Chronic Diseases: Comparison Between Arabs and Jews in Israel. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2024, 26, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.A.; Kim, D.; Lee, H. Examine Race/Ethnicity Disparities in Perception, Intention, and Screening of Dementia in a Community Setting: Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Tandy, A.; Balamurali, T.; Livingston, G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in use of dementia treatment, care, and research. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukadam, N.; Lewis, G.; Mueller, C.; Werbeloff, N.; Stewart, R.; Livingston, G. Ethnic differences in cognition and age in people diagnosed with dementia: A study of electronic health records in two large mental healthcare providers. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2023/424/11_23_424b.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Kahana, E.; Galper, Y.; Zilber, N.; Korczyn, A.D. Epidemiology of dementia in Ashkelon: The influence of education. J. Neurol. 2003, 250, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowirrat, A.; Treves, T.A.; Friedland, R.P.; Korczyn, A.D. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s type dementia in an elderly Arab population. Eur. J. Neurol. 2001, 8, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afgin, A.E.; Massarwa, M.; Schechtman, E.; Israeli-Korn, S.D.; Strugatsky, R.; Abuful, A.; Farrer, L.A.; Friedland, R.P.; Inzelberg, R. High Prevalence of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease in Arabic Villages in Northern Israel: Impact of Gender and Education. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 29, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowirrat, A.; Friedland, R.P.; Farrer, L.; Baldwin, C.; Korczyn, A. Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease in Israeli Arabs. Mol. Neurosci. 2002, 19, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neter, E.; Chachashvili-Bolotin, S. Ethnic Differences in Attitudes and Preventive Behaviors Related to Alzheimer’s Disease in the Israeli Survey of Aging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Gupta, A.; Oh, I.; Schindler, S.E.; Ghoshal, N.; Abrams, Z.; Foraker, R.; Snider, B.J.; Morris, J.C.; Balls-Berry, J.; et al. Association Between Socioeconomic Factors, Race, and Use of a Specialty Memory Clinic. Neurology 2023, 101, E1424–E1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, L.A.; Friedland, R.P.; Bowirrat, A.; Waraska, K.; Korczyn, A.; Baldwin, C.T. Genetic and Environmental Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease in Arabs Residing in Israel. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2003, 20, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi-Saliternik, R.; Friedlander, Y.; Cohen, T. Consanguinity in a population sample of Israeli Muslim Arabs, Christian Arabs and Druze. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2002, 29, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.; Glasser, S.; Murad, H.; Atamna, A.; Alpert, G.; Goldbourt, U.; Kalter-Leibovici, O. Depression among Arabs and Jews in Israel: A population-based study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 45, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.K.; Mokonogho, J.; Kumar, A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eylem, O.; De Wit, L.; Van Straten, A.; Steubl, L.; Melissourgaki, Z.; Danışman, G.T.; De Vries, R.; Kerkhof, A.J.; Bhui, K.; Cuijpers, P. Correction to: Stigma for common mental disorders in racial minorities and majorities a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Neurology. 2001. Available online: https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/home/GuidelineDetail/42 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Baron-Epel, O.; Weinstein, R.; Haviv-Mesika, A.; Garty-Sandalon, N.; Green, M.S. Individual-level analysis of social capital and health: A comparison of Arab and Jewish Israelis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.C.; Emily Choi, S.W.; Sun, F. COVID-19 cases in US counties: Roles of racial/ethnic density and residential segregation. Ethn. Health 2021, 26, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiscella, K.; Fremont, A.M. Use of geocoding and surname analysis to estimate race and ethnicity. Health Serv. Res. 2006, 41 Pt 1, 1482–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Jewish Participants (n = 8467) | Arab Participants (n = 6275) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 3646 (43.1%) | 2690 (42.9%) | 0.815 |

| Age at diagnosis (SD) | 80.150 (9.454) | 75.783 (10.276) | <0.001 |

| BMI and Lifestyle | |||

| Performing physical activity * | 1334 (20.9%) | 550 (10.2%) | <0.001 |

| Positive smoking history (current/past) ** | 2027 (25.8%) | 1821 (30%) | <0.001 |

| BMI (SD) *** | 27.094 (5.227) | 28.477 (6.090) | <0.001 |

| Background Diagnoses | |||

| Hypertension | 4714 (55.7%) | 3218 (51.3%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 3009 (35.5%) | 2970 (47.3%) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease (IHD) | 1896 (22.4%) | 1385 (22.1%) | 0.643 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) | 348 (4.1%) | 184 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke (CVA) | 2815 (33.2%) | 2142 (34.1%) | 0.259 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 1977 (23.3%) | 1879 (29.9%) | <0.001 |

| History of malignancy | 2356 (27.8%) | 687 (10.9%) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2881 (34.0%) | 2390 (38.1%) | <0.001 |

| Extrapyramidal disorders | 1233 (14.6%) | 472 (7.5%) | <0.001 |

| Essential tremor | 128 (1.5%) | 68 (1.1%) | 0.025 |

| Repeated falls | 1501 (17.7%) | 639 (10.2%) | <0.001 |

| Vision problems | 2965 (35.0%) | 2337 (37.2%) | 0.005 |

| Hearing problems | 1545 (18.2%) | 705 (11.2%) | <0.001 |

| Sleep apnea | 120 (1.4%) | 67 (1.1%) | 0.061 |

| Depression | 2417 (28.5%) | 985 (15.7%) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 307 (3.6%) | 114 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| Psychosis | 476 (5.6%) | 242 (3.9%) | <0.001 |

| Jewish Participants (n = 8467) | Arab Participants (n = 6275) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

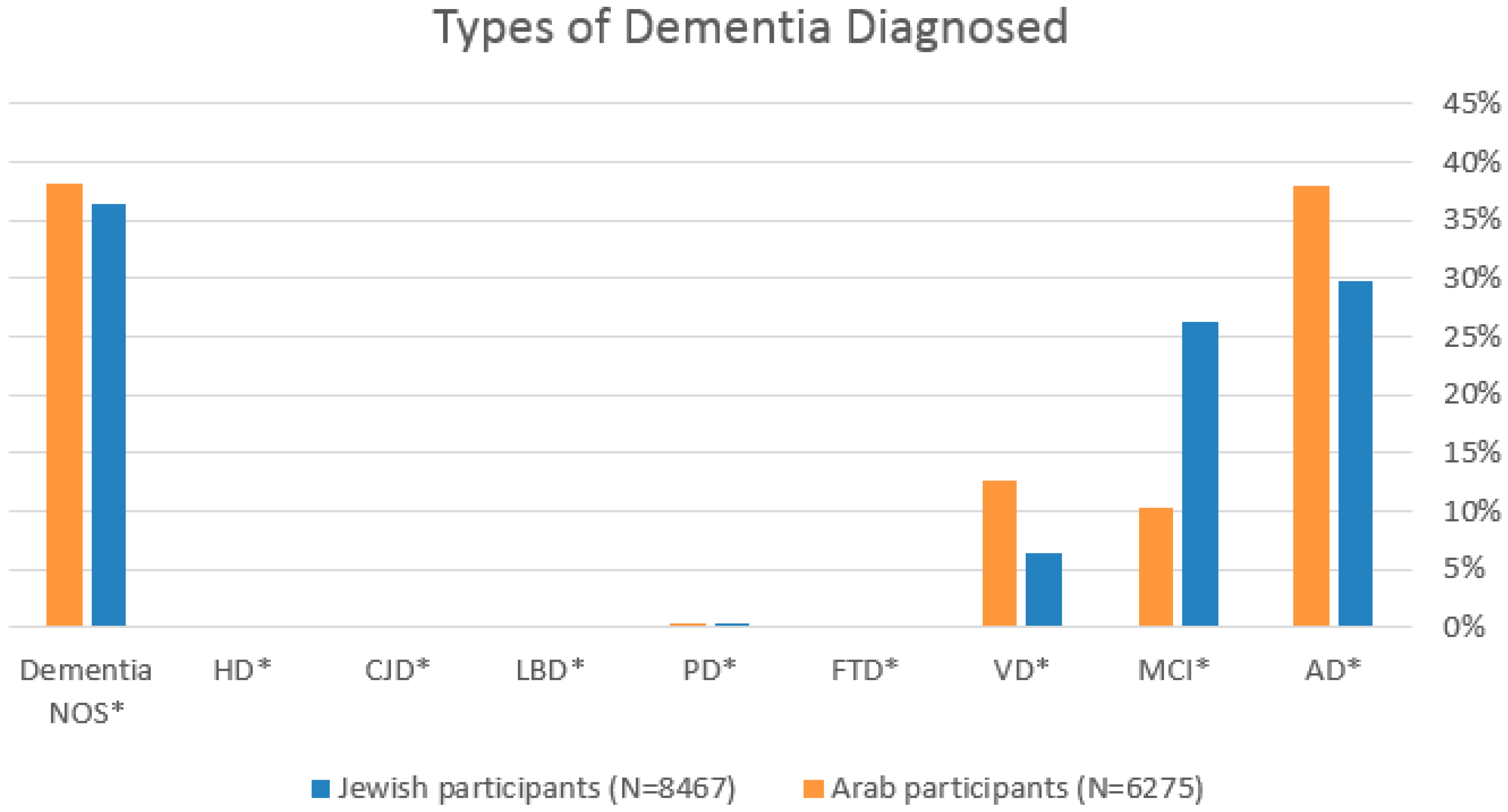

| Diagnosis | |||

| AD * | 2524 (29.8%) | 2387 (38.0%) | <0.001 |

| MCI * | 2227 (26.3%) | 647 (10.3%) | <0.001 |

| VD * | 540 (6.4%) | 789 (12.6%) | <0.001 |

| FTD * | 17 (0.2%) | 9 (0.1%) | 0.412 |

| PD * | 36 (0.4%) | 20 (0.3%) | 0.299 |

| LBD * | 7 (0.1%) | 3 (0.0%) | 0.421 |

| CJD * | 14 (0.2%) | 3 (0%) | 17 (0.1%) |

| Huntington’s disease | 7 (0.1%) | 8 (0.1%) | 15 (0.1%) |

| Dementia NOS | 3086 (36.4%) | 2400 (38.2%) | 5486 (37.2%) |

| Diagnosed By | |||

| GP | 3385 (68.2%) | 2630 (76.1%) | <0.001 |

| Neurologist | 388 (7.8%) | 397 (11.5%) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatrist | 18 (0.4%) | 13 (0.4%) | <0.001 |

| Geriatrician | 876 (17.7%) | 249 (7.2%) | <0.001 |

| Pediatrician | 215 (4.3%) | 102 (3.0%) | <0.001 |

| Work-Up | |||

| TSH | 8045 (95.0%) | 5354 (85.3%) | <0.001 |

| T4 | 5133 (60.6%) | 3293 (52.5%) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B12 | 7158 (84.5%) | 3938 (62.8%) | <0.001 |

| LDL | 7920 (93.5%) | 5855 (93.3%) | 0.572 |

| HBA1C | 5900 (69.7%) | 4737 (75.5%) | <0.001 |

| CT/MRI | 4282 (50.6%) | 3092 (49.3%) | 0.119 |

| Jewish Participants (n = 8467) | Arab Participants (n = 6275) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visits to neurologist per year (SD) | 1.502 (2.702) | 1.973 (3.084) | <0.001 |

| Visits to psychiatrist per year (SD) | 2.002 (3.179) | 2.707 (3.825) | <0.001 |

| Visits to geriatrician per year (SD) | 1.037 (2.164) | 0.893 (2.088) | <0.077 |

| Overall follow-up (years) | 6.805 (5.240) | 5.714 (4.909) | <0.001 |

| Three and more purchases of anti-dementia treatment | 2231 (82.4%) | 893 (73.0%) | <0.001 |

| Three and more purchases of antipsychotic medication | 1634 (63.5%) | 1350 (62.1%) | 0.360 |

| Jewish Participants (n = 8467) | Arab Participants (n = 6275) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education years (SD) | 13.917 (1.056) | 12.044 (0.633) | <0.001 |

| Percentage of academic degree holders (SD) | 43.284 (22.338) | 19.990 (6.162) | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) (SD) | 6.436 (3.126) | 3.237 (1.254) | <0.001 |

| Average monthly income in shekels (SD) | 8082.212 (3788.062) | 4094.808 (947.784) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bishara, H.; Cohen, H.; Hadar, D.; Specktor, P. Ethnic Differences in Dementia Diagnosis and Treatment in Israel. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175926

Bishara H, Cohen H, Hadar D, Specktor P. Ethnic Differences in Dementia Diagnosis and Treatment in Israel. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175926

Chicago/Turabian StyleBishara, Haya, Hilla Cohen, Dana Hadar, and Polina Specktor. 2025. "Ethnic Differences in Dementia Diagnosis and Treatment in Israel" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175926

APA StyleBishara, H., Cohen, H., Hadar, D., & Specktor, P. (2025). Ethnic Differences in Dementia Diagnosis and Treatment in Israel. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 5926. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175926