Reducing Caregiver Burden Through Dyadic Support in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review Focused on Middle-Aged and Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Evaluation of Risk of Bias and Methodological Quality of Studies

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

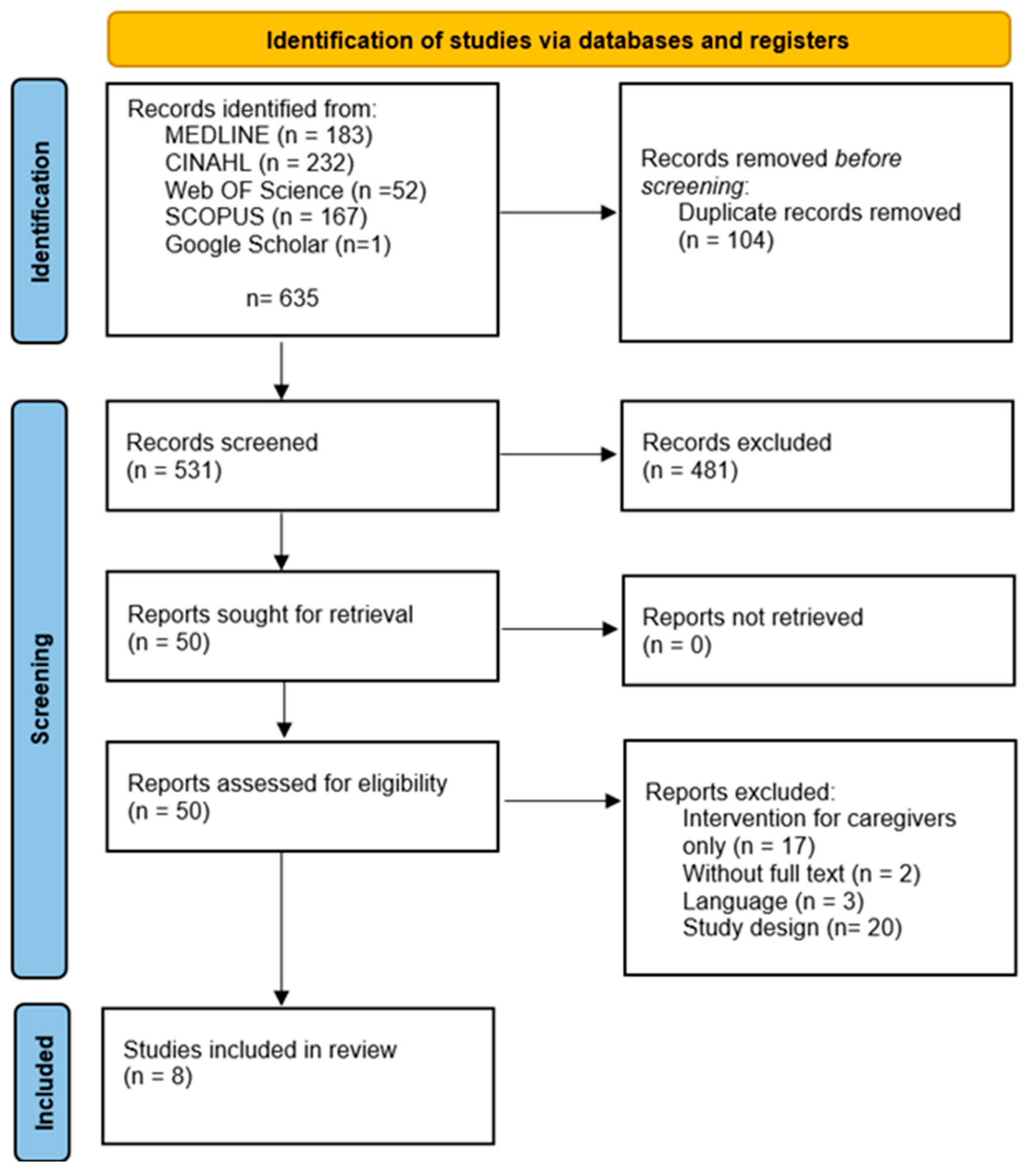

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Data Presentation

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Palliative Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Knaul, F.M.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Kwete, X.J.; Bhadelia, A.; Rosa, W.E.; Touchton, M.; Méndez-Carniado, O.; Enciso, V.V.; Pastrana, T.; Friedman, J.R.; et al. The evolution of serious health-related suffering from 1990 to 2021: An update to The Lancet Commission on global access to palliative care and pain relief. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e422–e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Casais, N.; López-Fidalgo, J.; Garralda, E.; Pons, J.J.; Rhee, J.Y.; Lukas, R.; de Lima, L.; Centeno, C. Trends analysis of specialized palliative care services in 51 countries of the WHO European region in the last 14 years. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 1044–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sítima, G.; Galhardo-Branco, C.; Reis-Pina, P. Equity of access to palliative care: A scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.; Normand, C.; Cassel, J.B.; Del Fabbro, E.; Fine, R.L.; Menz, R.; Morrison, C.A.; Penrod, J.D.; Robinson, C.; Morrison, R.S. Economics of Palliative Care for Hospitalized Adults With Serious Illness: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.; Espinosa, J.; Lucerna, A.; Parikh, N. Palliative and end-of-life care in the emergency department. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2022, 9, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, T.; Ramos, A.; Sá, E.; Pinho, L.; Fonseca, C. Contributions of the Communication and Management of Bad News in Nursing to the Readaptation Process in Palliative Care: A Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesonen, P.; Salminen, L.; Haavisto, E. Patients and family members’ perceptions of interprofessional teamwork in palliative care: A qualitative descriptive study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2644–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Pires, S.; Sá, E.; Gomes, I.; Alves, E.; Fonseca, C.; Coelho, A. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Perception of Individualized Nursing Care Among Nurses in Acute Medical and Perioperative Settings. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3191–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.P.; Chung, J.O.K.; Chan, H.Y.L.; Lo, R.S.K.; Li, K.; Lam, P.T.; Ng, N.H.Y. Effects of a structured, family-supported, and patient-centred advance care planning on end-of-life decision making among palliative care patients and their family members: Protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajani, Z.; Snell, D.; Wright, L.M. Wright & Leahey’s Nurses and Families: A Guide to Family Assessment and Intervention, 7th ed.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick, M.; Carter, B. The family life cycle: A systemic framework for family development. In The Expanded Family Life Cycle: Individual, Family, and Social Perspectives, 4th ed.; McGoldrick, M., Carter, B., Garcia-Preto, N., Eds.; Global ed. Pearson Education Limited; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, K.S.; Lee, C.S. The Theory of Dyadic Illness Management. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Zhu, X.; Shi, Z.; An, J. A serial mediating effect of perceived family support on psychological well-being. BMC Public. Health 2024, 24, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Salome, G.; Fisher, C.L.; Wright, K.B.; Lincoln, G.; Applebaum, A.J.; Sae-Hau, M.; Weiss, E.S.; Bylund, C.L. Impact of the family communication environment on burden and clinical communication in blood cancer caregiving. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocío, L.; Rojas, E.A.; González, M.C.; Carreño, S.; Diana, C.; Gómez, O. Experiences of patient-family caregiver dyads in palliative care during hospital-to-home transition process. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2017, 23, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Befecadu, F.B.P.; Gonçalves, M.; Fernandes, C.; Laranjeira, C.; Dixe, M.d.A.; Querido, A.; Pautex, S.; Larkin, P.J.; Rodrigues, G.D.R. The experience of hope in dyads living with advanced chronic illness in Portugal: A longitudinal mixed-methods study. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindt, N.; van Berkel, J.; Mulder, B.C. Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.E.; Denny, R.; Lee, P.G.; Montagnini, M.L. Palliative care considerations in frail older adults. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2024, 13, 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meleis, A.I.; Sawyer, L.M.; Im, E.O.; Hilfinger Messias, D.K.; Schumacher, K. Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle-range theory. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2000, 23, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Heymann-Horan, A.; Bidstrup, P.E.; Johansen, C.; Rottmann, N.; Andersen, E.A.W.; Sjøgren, P.; von der Maase, H.; Timm, H.; Kjellberg, J.; Guldin, M. Dyadic coping in specialized palliative care intervention for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: Effects and mediation in a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, A.; Marx, G.; Bergelt, C.; Benze, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wowretzko, F.; Heine, J.; Dickel, L.-M.; Nauck, F.; Bokemeyer, C.; et al. Supportive care needs and service use during palliative care in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: A prospective longitudinal study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, G.; Videira-Silva, A.; Carrancha, M.; Rego, F.; Nunes, R. Complexity of patient care needs in palliative care: A scoping review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2023, 12, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewtz, C.; Muscheites, W.; Grosse-Thie, C.; Kriesen, U.; Leithaeuser, M.; Glaeser, D.; Hansen, P.; Kundt, G.; Fuellen, G.; Junghanss, C. Longitudinal observation of anxiety and depression among palliative care cancer patients. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 3836–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Yu, T.T.F. Existential Suffering in Palliative Care: An Existential Positive Psychology Perspective. Medicina 2021, 57, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gan, J. Family resilience and social support as mediators of caregiver burden and capacity in stroke caregivers: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1435867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongelli, R.; Busilacchi, G.; Pacifico, A.; Fabiani, M.; Guarascio, C.; Sofritti, F.; Lamura, G.; Santini, S. Caregiving burden, social support, and psychological well-being among family caregivers of older Italians: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1474967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, N.; Hodgkin, S. Preparedness for caregiving: A phenomenological study of the experiences of rural Australian family palliative carers. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Rowland, C.; van den Berg, B.; Hanratty, B. Psychological morbidity and general health among family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A retrospective census survey. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Burgos, A.A.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Escribano, S.; Perpiñá-Galvañ, J.; Campos-Calderón, C.P.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Fatigue Assessment Scale in Caregivers of Palliative Care Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.; Morrison, R.S.; Schulz, R.; Brody, A.A.; Dahlin, C.; Kelly, K.; Meier, D.E. Improving Support for Family Caregivers of People with a Serious Illness in the United States: Strategic Agenda and Call to Action. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2020, 1, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Fonseca, C.; Pinho, L.; Lopes, M.; Brites, R.; Henriques, A. Assessment of Functioning in Older Adults Hospitalized in Long-Term Care in Portugal: Analysis of a Big Data. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 780364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, L.; Peng, X.; Xu, L.; Huang, L.; Wan, Q. Evaluating the effects of dyadic intervention for informal caregivers of palliative patients with lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2024, 30, e13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semonella, M.; Bertuzzi, V.; Dekel, R.; Andersson, G.; Pietrabissa, G.; Vilchinsky, N. Applying dyadic digital psychological interventions for reducing caregiver burden in the illness context: A systematic review and a meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yi, S.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Q. The efficacy of psychosocial interventions in relieving family caregiver burden in older adults with disabilities: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afaf155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaski, K.; Logan, L.R.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 1699–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauziah, H.F.N.; Rochmawati, E.; Padela, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of sleep hygiene implementation and its effect on sleep quality and fatigue in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J. Ners 2024, 19, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piamjariyakul, U.; Smothers, A.; Wang, K.; Shafique, S.; Wen, S.; Petitte, T.; Young, S.; Sokos, G.; Smith, C.E. Palliative care for patients with heart failure and family caregivers in rural Appalachia: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, B.M.; Katz, M.; Galifianakis, N.B.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Hauser, J.M.; Khan, R.; Friedman, C.; Vaughan, C.L.; Goto, Y.; Long, S.J.; et al. Patient and Family Outcomes of Community Neurologist Palliative Education and Telehealth Support in Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Heymann, A.; Finsted, E.; Guldin, M.B.; Andersen, E.A.W.; Dammeyer, J.; Sjøgren, P.; von der Maase, H.; Benthien, K.S.; Kjellberg, J.; Johansen, C.; et al. Effects of home-based specialized palliative care and dyadic psychological intervention on caregiver burden: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol. 2023, 62, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Wahba, N.M.I.; Zaghamir, D.E.F.; Mersal, N.A.; Mersal, F.A.; Ali, R.A.E.-S.; Eltaib, F.A.; Mohamed, H.A.H. Impact of a comprehensive rehabilitation palliative care program on the quality of life of patients with terminal cancer and their informal caregivers: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.; Journ, S.; Lee, S. Effect of Laughter Therapy on Mood Disturbances, Pain, and Burnout in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients and Family Caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 2024, 47, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzar, R.A.; Enzinger, A.C.; Poort, H.; Furey, A.; Donovan, H.; Orechia, M.; Thompson, E.; Tavormina, A.; Fenton, A.T.; Jaung, T.; et al. Developing and Field Testing BOLSTER: A Nurse-Led Care Management Intervention to Support Patients and Caregivers following Hospitalization for Gynecologic Cancer-Associated Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.F.; Lin, C.; Hung, Y.C.; Chang, L.F.; Ho, C.L.; Pan, H.H. Effectiveness of palliative care consultation service on caregiver burden over time between terminally ill cancer and non-cancer family caregivers. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 6045–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Bai, M. Effect of Family Music Therapy on Patients with Primary Liver Cancer Undergoing Palliative Care and their Caregivers: A Retrospective Study. Noise Health 2024, 26, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Search | Descriptors |

|---|---|

| #1 | “Dyad*” OR “Caregivers” OR “Family Caregivers” OR “Informal Caregivers” OR “Spouse Caregivers” OR “Carers” |

| #2 | “Palliative care” OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing” |

| #3 | “Caregiver Burden” OR “Caregiver Burnout” OR “Caregiver Stress” OR “Caregiving Stress” OR “Sickness Impact Profile” OR “Symptom Burden” |

| #4 | [(“Dyad*” OR “Caregivers” OR “Family Caregivers” OR “Informal Caregivers” OR “Spouse Caregivers” OR “Carers”) AND (“Palliative care” OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”) AND (“Caregiver Burden” OR “Caregiver Burnout” OR “Caregiver Stress” OR “Caregiving Stress” OR “Sickness Impact Profile” OR “Symptom Burden”)] |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Randomized Controlled Trials | ||

| Study | Score | Level |

| Piamjariyakul et al., 2024 [41] | 84.6% | High |

| Kluger et al., 2023 [42] | 84.6% | High |

| von Heymann et al., 2023 [43] | 76.9% | Moderate |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Tool of Quasi-Experimental Studies | ||

| Study | Score | Level |

| Ibrahim et al., 2024 [44] | 77.8% | Moderate |

| Moon et al., 2022 [45] | 77.8% | Moderate |

| Pozzar et al., 2022 [46] | 77.8% | Moderate |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Tool of Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies | ||

| Study | Score | Level |

| Wu et al., 2020 [47] | 100.0% | High |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Tool of Analytical Cohort Studies | ||

| Study | Score | Level |

| Ma et al., 2024 [48] | 87.5% | High |

| Publication | Country | Study Aim | Study Design | Setting | Sample/Participants | Data Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piamjariyakul et al., 2024 [41] | USA | To evaluate the effectiveness of the FamPALcare intervention program, which involves caring for individuals diagnosed with advanced heart failure and their family caregivers, including outcomes related to caregiver burden | Randomized controlled trial | At home, in rural communities in the Appalachian region | A total of 39 dyads. In the intervention group, 21 dyads; in the control group, 18 dyads. A total of 11 dyads did not complete the program (28%). Patients had a mean age of 65.66 years, with 66.7% male and 33.3% female. Family caregivers had a mean age of 62.05 years. | Baseline, 3, and 6 months |

| Ibrahim et al., 2024 [44] | Egypt | To assess the impact of a comprehensive palliative rehabilitation care program on the quality of life of individuals with incurable cancer and their family caregivers | Quasi-experimental study | Outpatient clinic of an oncology center | A total of 88 dyads. Patients had a mean age of 65.79 years, with 54.5% male. Family caregivers had a mean age of 42.05 years, with 49.1% female. | Pre- and post-intervention |

| von Heymann et al., 2023 [43] | Denmark | To evaluate the effect of specialized home-based palliative care, enhanced with a dyadic psychological intervention, on reducing the burden among family caregivers of patients with incurable cancer | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 249 dyads: 134 in the intervention group, 115 in the control group. Family caregivers: Intervention group—mean age 61 years, 63% female, 77% spouse/partner. Control group—mean age 62 years, 65% female, 80% spouse/partner. | 2, 4, and 6 weeks and at 6 months | |

| Wu et al., 2020 [47] | Taiwan | To assess the effectiveness of the Palliative Care Consultation Service (PCCS) in reducing the burden on family caregivers of patients with incurable progressive diseases, comparing oncological and non-oncological conditions | Prospective longitudinal study | Palliative care outpatient consultation at a medical center | A total of 68 dyads: 46 oncological; 22 non-oncological. Demographics (oncological): Patients—mean age 67.6 years (SD 15.3), 56.5% male. Caregivers—mean age 52.6 years (SD 10.5), 73.9% female, 65.2% not spouse. Demographics (non-oncological): Patients—mean age 83.6 years (SD 11), 50% male. Caregivers—mean age 56.4 years (SD 11.8), 79.1% female, 81.8% not spouse. | Baseline, day 7, and day 14. |

| Kluger et al., 2023 [42] | USA | To evaluate whether palliative care education for community neurologists, combined with telemedicine support, improves the quality of life of persons with Parkinson’s disease and related disorders (PDRDs) and reduces caregiver burden | Randomized controlled trial | Participants were discharged from hospitals in California, Colorado, and Wyoming | A total of 359 persons with PDRDs (179 intervention, 180 control), 300 family caregivers (143 intervention, 157 control), 143 dyads per group. Demographics (patients): Intervention—mean age 73.6 (SD 9.1), 62% male. Control—mean age 74.4 (SD 7.6), 67.8% male. Demographics (caregivers): Intervention—mean age 65.8 (SD 12.1), 78.2% female, 72% spouse/partner, 21% child, 7% other. Control—mean age 69.2 (SD 10.3), 65% female, 82.1% spouse/partner, 11.5% child, 6.4% other. | 6 and 12 moths |

| Moon et al., 2022 [45] | South Korea | To evaluate the effects of laughter therapy on mood disturbance and pain in patients with terminal cancer and caregiver burden in family caregivers | Quasi-experimental study | Palliative care ward in a tertiary university hospital | A total of 49 dyads (26 in intervention, 23 in control). Patients (intervention): mean age 61.04 (SD = 12.61), 76.9% male. Patients (control): mean age 60.83 (SD = 10.63), 69.6% male. Caregivers (intervention): mean age 50.19 (SD = 16.51), 80.8% female. Caregivers (control): mean age 55.35 (SD = 12.59), 56.5% female. | Pre- and post-intervention |

| Ma et al., 2024 [48] | China | To evaluate the effectiveness of family music therapy in reducing emotional and physical distress in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients in palliative care and their family caregivers | Retrospective cohort study | Palliative care ward | A total of 120 dyads (65 intervention, 55 control). Patients aged 18–80 with stage III–IV hepatocellular carcinoma. Intervention group (mean age 62.6 years, 64.6% male), control group (mean age 66.7 years, 54.5% male). Caregivers: intervention group (mean age 46 years, 73.9% female), control group (mean age 48 years, 74.5% female). | Pre- and post-intervention |

| Pozzar et al., 2022 [46] | USA | To develop and field-test a nurse-led care management intervention (BOLSTER) to support patients and caregivers following hospitalization for gynecologic cancer-associated peritoneal carcinomatosis | Quasi-experimental study | Acute hospitalizations | A total of 6 dyads: 6 patients were an average of 64 (SD = 7.31) years old, and 6 caregivers were an average of 64 (SD = 6.63) years old. | Pre- and post-intervention |

| Publication | Intervention Providers | Dyadic Support Program Content | Intervention Frequency | Instruments | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piamjariyakul et al., 2024 [41] | Nurses | Named FamPALcare, the intervention includes telephone coaching focused on education, emotional support, and advanced care planning. The intervention group received a manual to follow during sessions, an assessment of family beliefs and concerns, guidance on caregiver involvement, and identification of home care needs. | A total of 5 telephone sessions lasting 60 to 90 min | Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4), Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-12), Helpfulness Rating Scale (HRS-11) | The most valued aspects were strategies for managing advanced heart failure symptoms, information about advanced directives and legal documents, and the comfort of discussing care options with family and healthcare professionals. The disease trajectory chart was considered less useful. Caregivers showed a progressive reduction in burden over 6 months, along with decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression. Patients demonstrated improvement in health status and quality of life, with consistent progress from the 3-month mark. |

| Ibrahim et al., 2024 [44] | Health professionals qualified in physiotherapy, psychoeducation, counselling, and spiritual care | A rehabilitation program that encompassed physical exercise, psychological education, one-on-one support sessions, and, notably, elements focused on spiritual and existential matters. | A total of 16 sessions, between 10 and 60 min | Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI), European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) | A sharp reduction in anxiety levels and a more moderate decrease in depressive symptoms were observed. Significant improvements were noted across various domains of quality of life, including physical capacity, functional performance, emotional role, and mental health, with slight progress in social functioning. There was also an overall reduction in caregiver burden, particularly with improvements in the physical and emotional aspects of caregiving. |

| von Heymann et al., 2023 [43] | Specialized palliative care nurses | The initial two sessions focused on needs assessment and therapeutic alliance. Follow-up sessions were dyadic or individual, tailored to each dyad’s needs. Oncology treatments and home care continued concurrently. | First 2 sessions within the first month; subsequent sessions scheduled Flexibly over 6 months according to dyad needs | Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12) | No significant effect on overall caregiver burden. Small effect sizes were observed (from 0.35 to −0.85) on total burden, personal strain, and role strain subscales. |

| Wu et al., 2020 [47] | Palliative care team (specialists, palliative nurses, social workers, chaplain) | Palliative Care Consultation Service (PCCS)—initial assessment by physician and nurse, follow-up, multidisciplinary weekly meetings and care planning. | Follow-up 1–2x/week; service ends upon symptom control, resolution of problems, or transfer/discharge/death | Symptom Distress Scale—patients (SDS-CMF), Family Caregiver Burden Scale (FCBS) | Caregiver burden (FCBS) decreased in both groups. Greater reduction in physical–psychological and spiritual burden for oncological caregivers; greater reduction in daily activity and financial burden for non-oncological caregivers. |

| Kluger et al., 2023 [42] | Community neurologists and a specialized palliative care team via telemedicine | Telemedicine-based palliative care. Included education for neurologists and additional support to the dyad (person and caregiver) via a telemedicine team. Follow-up and decision-making support provided remotely. | 12 months | Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12), Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD—patient), Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS—patient), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS—patient and caregiver), McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQLQ—patient), Prolonged Grief Questionnaire (PGQ), Modified Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT—caregiver) | While the intervention improved the perceived clinical trajectory at 6 months, it did not reduce caregiver burden. Some indicators of burden and strain increased over time in the intervention group. This may reflect a greater awareness of caregiver challenges resulting from closer engagement with palliative care teams, rather than a failure of the intervention itself. |

| Moon et al., 2022 [45] | A total of 2 certified laughter therapy specialists and 1 nursing professor (oncology care) | The laughter therapy program was conducted with groups of 3 to 4 pairs at a time, either in the morning or in the afternoon, in a private room within the hospice ward. | Daily sessions of 20–30 min for 5 consecutive days | Linear Analogue Self-Assessment (LASA—patients and caregivers, Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), Burden Measure (BM) | The intervention group showed a significant reduction in caregiver burden, emotional distress in both patients and caregivers, and pain levels in patients. In contrast, the control group experienced increases in all these outcomes. |

| Ma et al., 2024 [48] | Palliative care team and music therapists | Family music therapy via WeChat: 30 min daily sessions of relaxing and uplifting music for 4 weeks, with guidance on listening posture and volume. | A total of 30 min each time once a day, and the treatment lasting for 4 weeks | Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Cancer-Related Fatigue Scale (CFS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Anticipatory Grief Scale (AGS), Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) | Patients showed significant reductions in depression, anxiety, and fatigue. Caregivers had improved sleep quality, reduced anticipatory grief, and decreased caregiver burden. |

| Pozzar et al., 2022 [46] | Nursing and oncologists | BOLSTER program with nursing visits, starting at home and continuing via telehealth or phone or in person. Symptom monitoring, personalized education, goal setting, digital support through a mobile app, printed materials, and educational videos. | Intervention of 10 weeks comprising 12 nurse visits | EuroQol 5 Dimensions 5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Palliative Care (FACIT-PAL), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) | All patients and caregivers who completed interviews recommended the BOLSTER program, expressed satisfaction with the sessions, and felt it helped patients understand their illness. Most also agreed it improved symptoms, supported coping, and assisted with future planning. |

| Publication | Patient and Caregiver | Patient | Caregiver | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depressive Symptoms | Functional and Social Performance | Quality of Life | Symptom Control | Burden | Anticipatory Grief | |

| Piamjariyakul et al., 2024 [41] | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | ||

| Ibrahim et al., 2024 [44] | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | |||

| von Heymann et al., 2023 [43] | (0) | ||||||

| Wu et al., 2020 [47] | (+) | (+) | |||||

| Moon et al., 2022 [45] | (+) | (+) | (+) | ||||

| Ma et al., 2024 [48] | (+) | (+) | (+) | ||||

| Pozzar et al., 2022 [46] | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | |||

| Kluger, et al., 2023 [42] | (-) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Botas, G.; Pires, S.; Fonseca, C.; Ramos, A. Reducing Caregiver Burden Through Dyadic Support in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review Focused on Middle-Aged and Older Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5804. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165804

Botas G, Pires S, Fonseca C, Ramos A. Reducing Caregiver Burden Through Dyadic Support in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review Focused on Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(16):5804. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165804

Chicago/Turabian StyleBotas, Gonçalo, Sara Pires, Cesar Fonseca, and Ana Ramos. 2025. "Reducing Caregiver Burden Through Dyadic Support in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review Focused on Middle-Aged and Older Adults" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 16: 5804. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165804

APA StyleBotas, G., Pires, S., Fonseca, C., & Ramos, A. (2025). Reducing Caregiver Burden Through Dyadic Support in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review Focused on Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(16), 5804. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165804